Meet Me in the Bathroom is a New York indie sleaze time capsule

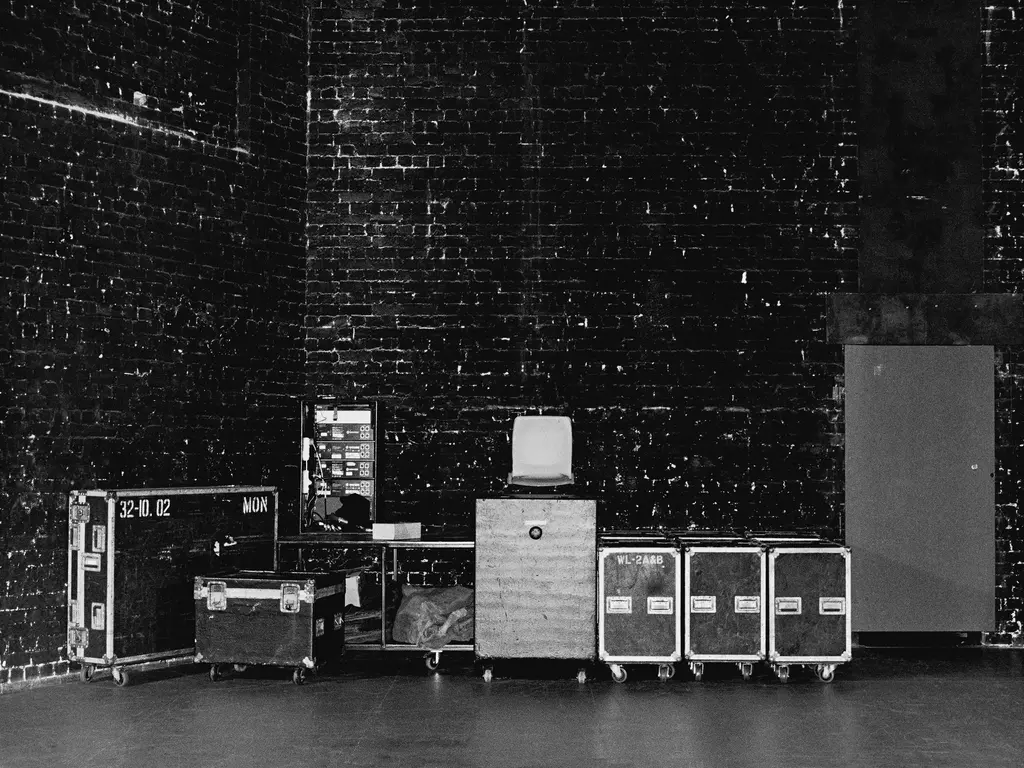

Photograph by Hedi Slimane

London Film Festival: The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and LCD Soundsystem bare all in a brilliant documentary about the early Noughties scene.

Music

Words: Craig McLean

Meet Me in The Bathroom is the documentary of the book of the scene that – briefly – changed the world. The music world, that is, with a bit of a knock-on into fashion, too.

Long before it was rebranded as “indie sleaze”, the tumble of bands that began emerging from New York in 2001 was the most exciting thing to happen in guitar music in an incredible [checks yellowing, dog-eared print copies of NME] THREE YEARS, since a coke-bloated Oasis started phoning it in.

The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, LCD Soundsystem, TV On The Radio, The Moldy Peaches, Interpol, The Rapture – just over half of those bands (you can guess which four) were genuinely game-changing. The others added to the vibe and the sense that the Lower East Side and Brooklyn were the most exciting places on earth, a 24/7 rock’n’roll riot of dive bars, warehouse living and endless parties where everyone was high on their own DIY talents – and on whatever intoxicants were going. And, with singles like House of Jealous Lovers, they also offered a glimpse of a new, dancefloor-friendly future for rock music.

Celine’s creative director Hedi Slimane was there, photographing the bands and the atmosphere – a curated selection of his black and white images, some of them appearing here, are being released as a limited-edition poster to accompany the film’s US theatrical release.

THE FACE was in the thick of it, too. In late spring 2001, the magazine commissioned Colin Lane to photograph The Strokes for one of their first UK interviews. Suitably impressed by the resulting images that appeared in our pages, the band subsequently used one of Lane’s archive images, an “ass shot” of his ex-girlfriend, for the cover of Is This It, the groundbreaking debut album released that July.

Anyway. There are much more interesting stories aplenty in Meet Me in the Bathroom. It’s directed by British filmmaking duo Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern, who previously shot 2010 Blur reunion tour movie No Distance Left To Run and LCD Soundsystem’s “farewell” concert film Shut Up and Play the Hits (2012). Their doc is an adaptation of the masterful oral history of the same name by Lizzy Goodman, who was a journalist at Spin at the time. Her 2017 book was crafted from over 200 interviews, subtitled Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001 – 2011, and ran to 640 pages.

Lovelace and Southern couldn’t hope to replicate all that if they wanted to make a film that was shorter than, say, the period in which The Strokes remained genuinely ace. So they concentrated on a handful of core bands, and the first three years of the scene no one was calling Now Wave.

Their methodology: artful repurposing of journalists’ period interviews with bands (full disclosure: I supplied some); archive footage from gigs, TV appearances and video outtakes; some top-up, current interviews with any artists willing to step forward again; and absolutely no contemporary talking heads.

The result: a brilliant evocation of a super-buzzy time, punctuated by 9/11, that offered thrilling highs and, inevitably, bummer lows. Meet Me in the Bathroom pulls no punches in showing both extremes.

Ahead of its cinema release in January 2023, we talked to the directors of Meet Me in the Bathroom as they prepared for their documentary’s UK premiere at the London Film Festival.

As Brits who were not long out of college [Liverpool John Moores University] at the time that these bands were breaking through, how important was your outsiders’ perspective in getting this gig?

Will Lovelace: With all the music films we’ve made, we’ve never really been known to the people before making them – we made a film about Blur, and we didn’t know the guys at all. Being neutral in that sense, not having a relationship with them, works. And it’s probably not a bad thing that we were sort of discovering [the scene] from a distance rather than having been there.

Lizzy Goodman, at the beginning of her book, talks about being in the crowd at what was then LCD’s last show at Madison Square Garden and thinking: “I need to write this down. This is the end of that period.” And then obviously us making a film about that night, it felt like a great fit.

Any downsides to being non-Americans who weren’t there at the time?

Dylan Southern: Sometimes it went against us. We knew James [Murphy, LCD Soundsystem] and we knew people that knew some of the other bands, so we had access there. But it became more a case of starting from the beginning, in terms of getting the other bands who had already done the book to come on board and be involved.

There was a certain amount of diplomacy involved because the book made quite a big splash, and because people tend not to want to repeat themselves. So getting them to trust us with their stories took quite a bit of time at the beginning.

I’m guessing [Strokes singer] Julian Casablancas didn’t do a new interview. He’s one of the most difficult interviewees I’ve ever encountered. Not because he’s a dick, just because he was profoundly uncomfortable from the get-go about being thrust into the spotlight. You see that in some of the earliest filmed interviews in your film, notably when they first come to London. And it obviously didn’t get any better over the subsequent years. What did you come to understand about Julian over the course of making this film?

Southern: Julian didn’t [do a new interview], no. The overwhelming feeling was that I liked him more than I thought I would, going in. He’s an incredibly complex character, and incredibly driven. His focus was making music that satisfies him as an artist. But then he also wanted it to be incredibly popular as well. So there’s two forces in him up against each other.

There’s a really awkward interview with [“comedy” media personality] Nardwuar the Human Serviette, who’s from Canada. It’s very, very early on, I think it might be at South by Southwest. And Nardwuar is needling Julian about his dad [John Casablancas, founder of Elite Model Management], and about that whole aspect of who he is. And you can just see that it’s painful for him. They all do have a little bit of a [boujie background]. It’s a good job they’re not an English band, because with that background, they’d be taken down straight away. But it still was a big thing.

Photography by Hedi Slimane

Photography by Hedi Slimane

Photography by Hedi Slimane

Photography by Hedi Slimane

Photography by Hedi Slimane

Also from The Strokes, we hear about guitarist Albert Hammond Jr. He was, conversely, the most fun Stroke to interview. But he was the one who fell hardest, ultimately, with his descent into heroin addiction. You feature that narrative, and Ryan Adams’ alleged role in that. What were the discussions around including those elements?

Lovelace: With all of them, they’d obviously talked about it in the book. So you had that starting point, and it felt like it was part of their story that they had been willing to talk about, and it was an important part. So it had to be in the film.

Southern: There was a lot of consternation about how much screen time to give Ryan Adams given where he’s ended up [accused of sexual misconduct by seven women]. That was a difficult thing. I don’t think he comes off well in the film, but he does have an impact on The Strokes’ story. So we felt like that aspect of it needed to be included.

We also see the toll that being a woman in a very male-dominated scene took on Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Karen O. Well, actually, the toll that male objectification took on her. One of the most powerful portions of your film is the single-take shot from the Maps video, where she starts crying. What is the importance of that out-take?

Lovelace: It was amazing that they were willing to let us get the rushes from that video. It’s such a special song for them, and for all of their fans, and for that time. So it was great to be able to use that footage and show it in a slightly different way than the [final] edit for the music video. That’s the culmination of Karen’s story, and we were able to use that footage to help show that transformative moment in her story.

What would you say is the legacy of this scene, this music and these bands?

Lovelace: There was this moment, and actually it was quite brief, where people made some amazing music in a city that was rapidly changing.

Southern: And, hopefully not, but it seems like the last time that that might happen. Just because the world has changed so significantly in terms of how we consume music, how we consume culture, how we use technology. Could there be a groundswell again of bands who are all part of some thriving music scene that’s geographically specific? There will certainly be scenes again, and things that rise up in the culture. But whether it will ever happen that way again is another question.

FACE readers who may not even have been born when Is This It came out – what can they get from this film?

Lovelace: If readers of THE FACE, or people of a younger age, aren’t aware of this music, I mean, wow. At the very least, that’s an amazing thing to discover.

Being able to dive into a scene and a moment and immerse yourself in it was part of our ambition: to make a film that took you back there, and hopefully made it feel like what it was like to be there.

Southern: I’d actually be interested to find out the answer to that question. We’ve heard a lot from people who’ve read the book, and then watched the film, and they obviously had a pre-existing interest in it. So you can take it as read what their view will be.

I certainly think younger people will see a completely different world [in the doc]. A world pre‑9/11, and pre-internet, pre-social media – everything that makes the world culturally what it is for them today. And I think the music’s great.

Meet Me In the Bathroom screens on 14th, 15th and 16th October. Ticket info