The sound of England

Inspired by cyphers, sound systems and local music heroes, these cutting-edge artists are keeping folk tradition alive.

Music

Words: Davy Reed

Photography: Joshua Gordon

Taken from the new print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

For all its flaws, England is a country with a rich variety of regional subcultures. Drive in any direction for 50 miles and you’ll end up somewhere with different slang delivered in different accents, a place where local traditions and stars help tell a story about the area’s geography, post-industrial legacy and ethnic makeup.

Permeating all England, for all time, is folk culture, both uniting and distinguishing. That idea probably conjures images of performers solemnly plucking acoustic guitars. But in the 21st century, England’s folk culture is shared or learned in grotty nightclubs, playground cyphers and Carnival sound systems, or via tinny phone speakers and no-budget music videos. It’s not the style that makes it folk – it’s the onward transmission.

Those grassroots traditions are, by definition, real. And one thing all great music has in common is authenticity. Listen closely to any decent track and you’ll be able to hear the artist’s unique charisma. If the pain in their voice is truthful, if their appetite for the rave is genuine. In a music industry that measures success with streaming stats and virality, encouraging artists to smooth over their edges and submit to the demands of the algorithm, sometimes you’ve got to search the periphery to find the good stuff.

Here, we celebrate artists who, in their uncompromising recasting of local sounds, are keeping a very modern iteration of England’s folk tradition alive. They tell us about the music, scenes and people that raised them, and why they’ll never forget where they came from.

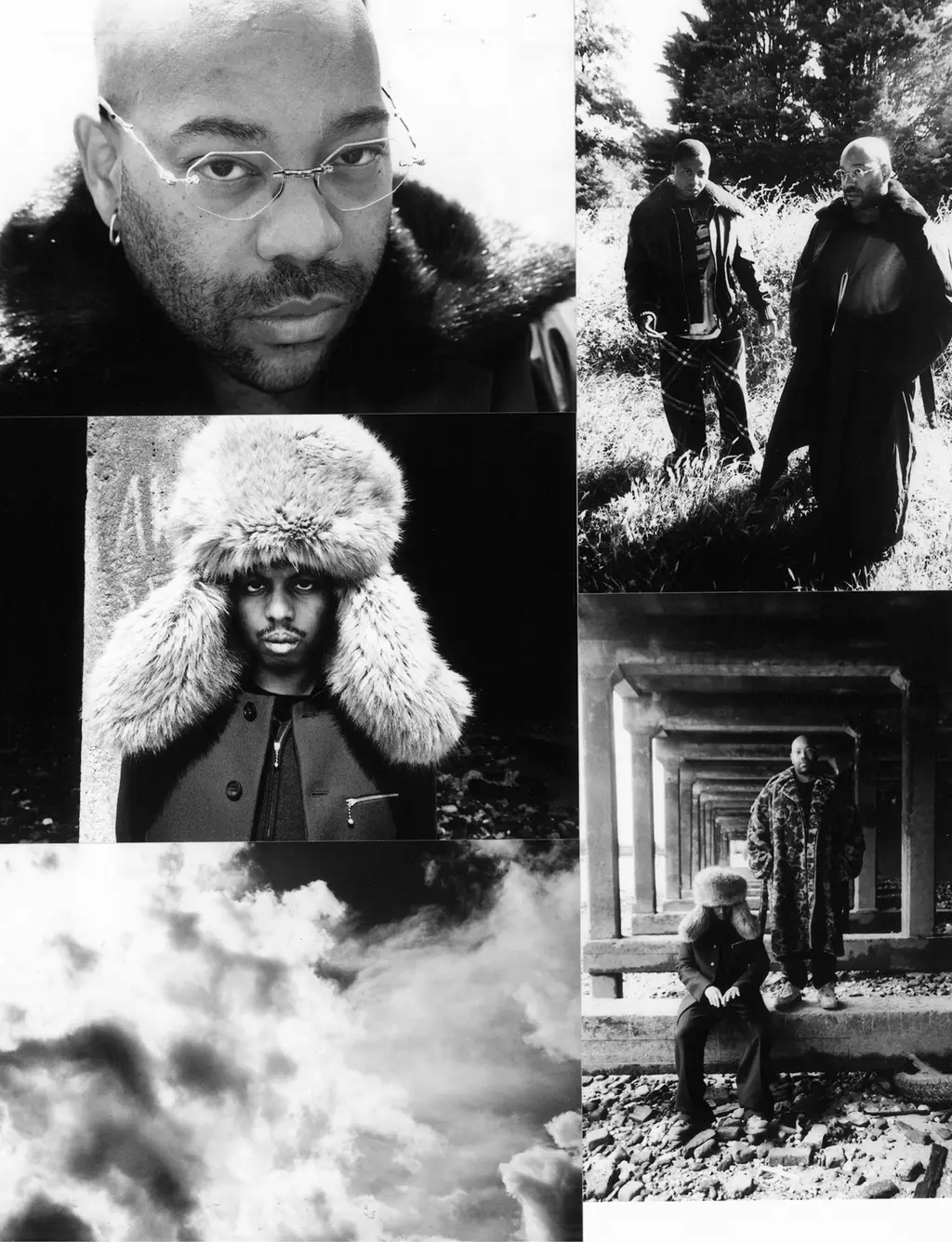

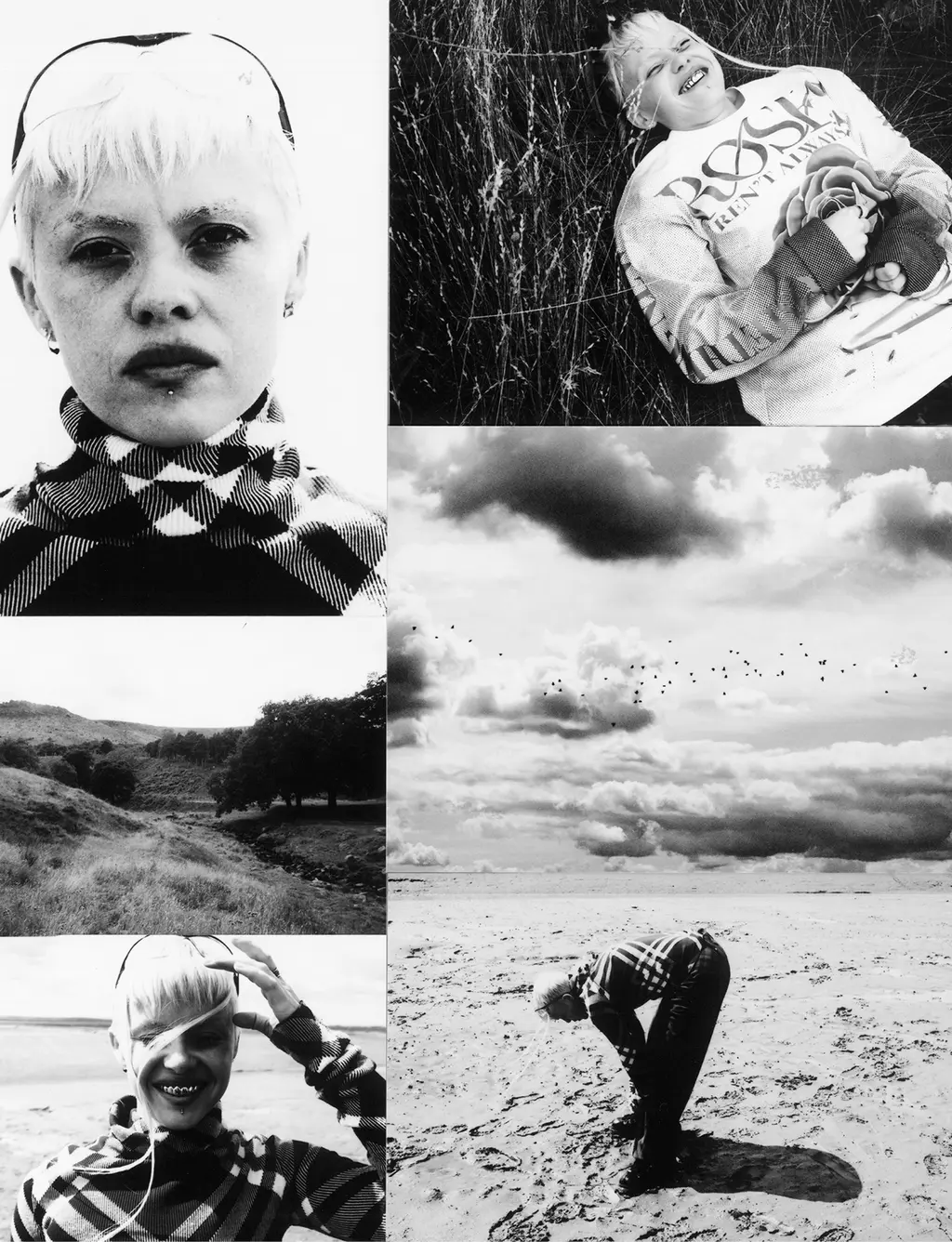

SPACE AFRIKA

Joshua Inyang and Joshua Reid wear all clothing, hat and shoes BURBERRY

There was a point, during the dark days of 2020, when the thought of new music scenes emerging felt like a distant hope. But something real was crystallising in the North West as the Tory government’s treatment of Manchester during the pandemic (less funding, stricter lockdowns) brought into focus age-old regional inequalities. The city, though, has always had a reputation for unblinking confidence and resilience, and that spirit trickles down to its underground music scene.

Childhood friends Joshua Inyang and Joshua Reid had been putting out music as Space Afrika since 2014, delicately smudging techno beats with dusty distortion for their early releases. But 2020 was the year of their belated breakthrough, and when more like-minded experimentalists gravitated towards them. Space Afrika’s mixtape hybtwibt? [Have You Been Through What I’ve Been Through?] – a collage of beat-less music, tender voice samples and field recordings released days after the murder of George Floyd – caught the ear of Rainy Miller. The producer, singer and label owner from Lancashire was helping his friend Tom Heyes, aka Blackhaine, shape a left-field drill sound for his raw poetry.

Rainy reached out to ask permission for a sample and, immediately afterwards, Inyang, Miller and Blackhaine got together in a Salford studio and began working on their track B£E, with Reid contributing remotely from his new home of Berlin. The avant-garde collab, about finding faith in a dark place, which was released in 2021, references Manchester’s bee emblem and became an anthem of sorts for the burgeoning local underground scene.

As lockdown restrictions eased, Space Afrika found a physical home at The White Hotel, the renowned Salford venue named after D.M. Thomas’s erotic 1981 novel, which platforms strange music, provocative performance art and free-spirited hedonism. Although they’ve since transcended the local scene, touring globally and building an international network of collaborators, they’re bringing it back to the North West with their next release, a joint longform project with Rainy to be released later this year.

“You’re being bombarded by all these different sounds from different clubs while walking through the city centre. Our early productions were taking all those inspirations with us”

JOSHUA REID, SPACE AFRIKA

Joshua Reid and Joshua Inyang wear all clothing, hat and shoes BURBERRY

Joshua Reid and Joshua Inyang wear all clothing, hat and shoes BURBERRY

When did you guys meet, and what are your memories of Manchester at that time?

Joshua Reid: We met in South Manchester around the age of eight. We went to slightly different schools, but [in] the same parish. We joined up on this extracurricular programme for children who were involved in sport, mathematics, verbal reasoning and English. We hit it off, basically, on the fact that we had the same name. Our parents hit it off as well. Historically, Manchester has an industrial context to it. And both of our parents [were] working hard and coming from a different background as well.

What are your parents’ backgrounds?

Joshua Inyang: [Mine are] both Nigerian.

JR: My family’s from Jamaica.

When did you form a musical connection?

JR: Around the age of 14. We’re talking the era of sharing music by Bluetooth, Infrared and MSN. Sharing music downloaded from Limewire. You’re in school, and you’re going from school straight home, but there was just enough creativity in the city – [it] was happening in public spaces, on street corners in the city centre.

JI: Predominantly, you’d be watching Channel U and MTV – the R&B and hip-hop videos at that time were super fresh. Channel U had one of the strongest impressions on us, definitely. It’s when all the technology started getting relatively cool, around Y2K. You had the Sony Ericsson phones, the white ones with the orange trim. There would be loads of us in the playground with the Walkmans, or playing the music off the phone speakers, or creating cyphers.

Manchester’s famous for being a good night out. Did you bond over clubbing when you got a bit older?

JR: Coming of age in a city which has a history of rave culture or whatever, obviously, the Haçienda house [music] thing is a super big overlay on the city. But that’s one side of the city. The side that we grew up on, it was much more common to go to Music Box, where there were grime raves, bassline nights. I remember taking trains to Leeds to go to bassline nights and Sheffield to go to Niche. And there was localised grime stuff going on, so we actually bonded through, like Josh said, doing those cyphers on the streets. Obviously, as you get a bit older, you gravitate towards the inner city clubs. But we also visited those clubs which played rap and R&B.

JI: Yeah, clubs like Boutique and M‑Two. So our initial listening experiences were with a lot of Black, Afro-Caribbean culture and music. Then [we] were progressing into different forms of clubbing and music on the more electronic side of things. There was that bridge with garage, grime and two-step, and then the dubstep period.

Your music feels really nocturnal. Do you take a lot of inspiration from Manchester at night?

JR: It definitely seeps into our music. Not necessarily the experience of being in the clubs, but being between the clubs. You go down Oldham Street, which has house music playing, jungle, drum ’n’bass, dubstep and R&B. You’re being bombarded by all these different sounds from different clubs while walking through the city centre, trying to get from A to B. On our early productions we were taking all those inspirations with us. And the formula for that was, like, dub techno. Because the music that we grew up listening to follows that format of dub.

The White Hotel, where you, Rainy Miller and Blackhaine shot the video for B£E, is right by Strangeways prison, and there’s a very powerful ambience in the area. How has the venue influenced Space Afrika?

JI: Our first live set was at The White Hotel. When we were given that opportunity, it [felt] like there was a home for us, there’s an ear that’s ready and receptive to understand the music that we’re trying to make. It was always a safe zone, or a fertile ground for us to just be ourselves. I think the location has this weird, derelict beauty to it. And the associations to the [D.M. Thomas] book kind of animate it as this fantastical thing. We just went to Australia for the first time and someone in the green room was telling us all about The White Hotel and all about Manchester.

How does it feel to be from a city with such a massive musical heritage?

JI: Until someone asked me that question, it had never even crossed my mind. I started listening to the iconic Manchester bands and watching documentaries about them in the last few years and realised: “Oh, that phrase someone was using was the title of this, which is about that band…” It is very nice to be considered in some sort of lineage of something that was super important to a particular place or time. But it’s not anywhere, really, in the mindframe when we’re producing work.

JR: It’s nice to be referenced in that frame. But at the same time, it’s also limiting, in terms of trying to transcend the location that you’re in. Because it becomes so bound to a history. That’s what happened with dance music in Manchester, with The Haçienda. It took so long for those ropes to become unshackled. Our generation, it’s important that we’re able to start telling our own stories.

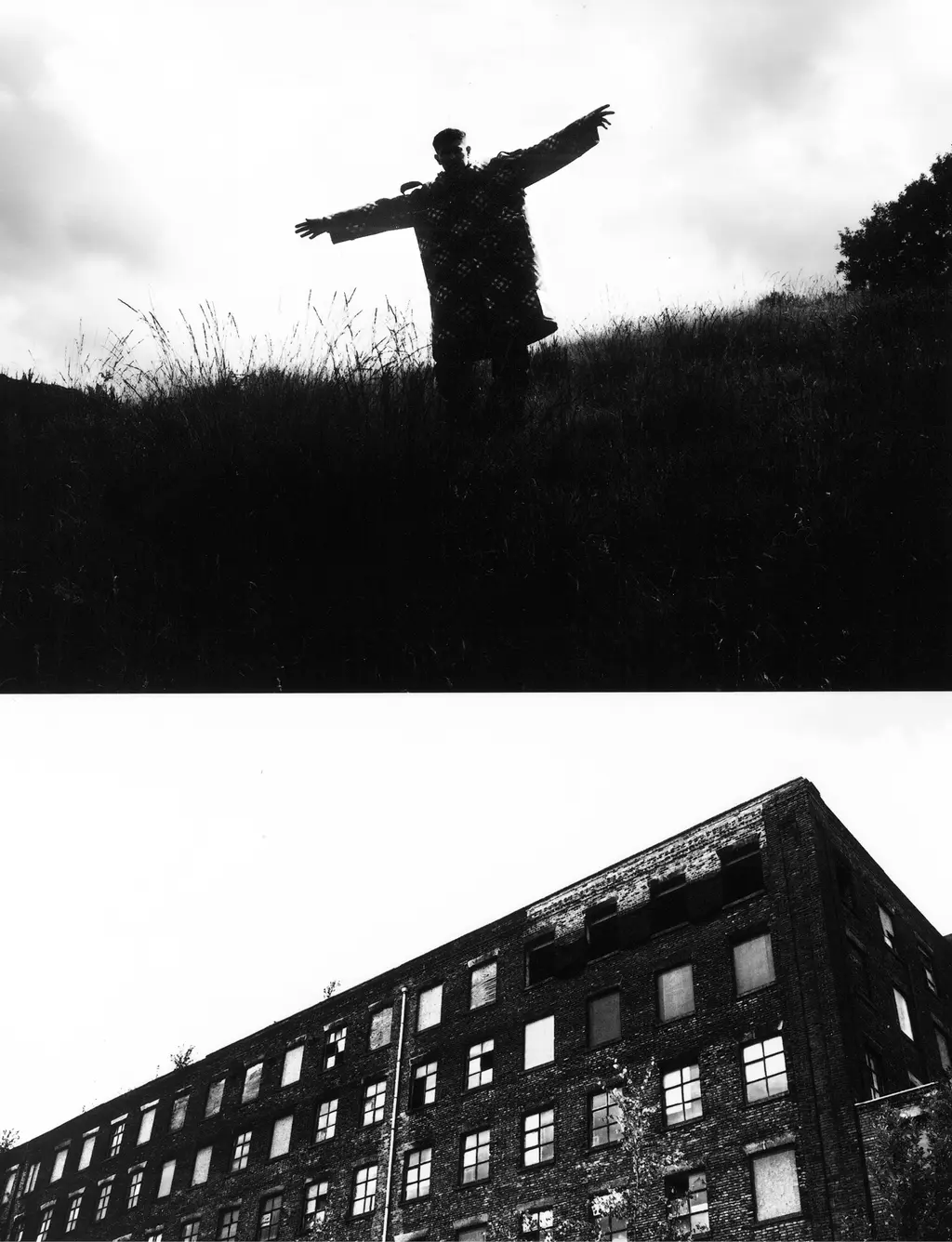

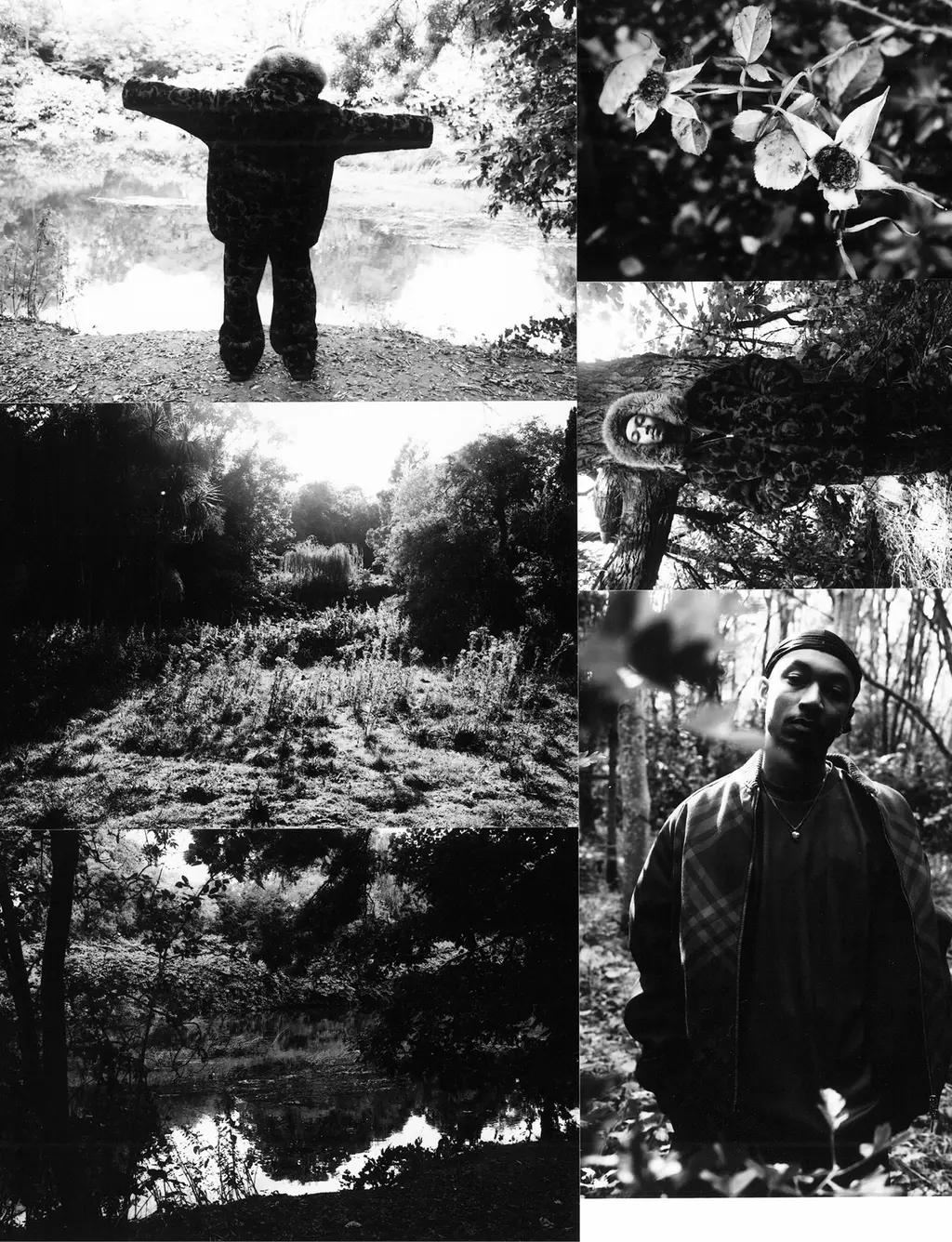

RAINY MILLER

Rainy wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

Rainy Miller, birth name Jack Bowes, was born and bred in Longridge, a small market town eight miles from Preston.

Growing up, the 28-year-old dabbled in grime and then hip-hop production, but at first he didn’t see a career for himself as a professional musician, instead completing a sports college course and then starting a job at a factory when he turned 18. Eventually, at 21, he moved to Manchester to enrol on a uni degree in audio engineering, which set him on a path towards his R&B‑orientated debut album Limbs (2019), released via his own label Fixed Abode.

As a label head, producer and mixer, Rainy has helped nurture many artists in the North West’s experimental music scene, including Space Afrika, Manchester-based singer-rapper Iceboy Violet and fellow Lancastrians Blackhaine and Moseley. His own music functions as a way for him to process trauma and heal. And although Rainy bends his melodies and morphs his voice with AutoTune, his Prestonian accent cuts through on every track.

“We were ripping grime beats from Limewire. Everyone was recording tracks. Grime was the first thing that really gripped Preston “The Preston mentality is just super cynical. But we’ll get there. I’ll always work harder to in any kind of way that was relevant to me”

RAINY MILLER

Rainy wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

Rainy wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

What music did you hear around Preston when you were growing up?

At the beginning, it was strictly music from Preston. Grime had probably been in London from around 2000 onwards, but it only took off in Preston around 2006. I was just finishing primary school and getting into high school, and it was the maddest thing. You couldn’t move without finding someone who was an MC. It was the most rudimentary thing ever. We were ripping grime beats from Limewire, then going around to a mate’s house; he managed to get a hold of some SM58 microphone that they could plug into a computer. Everyone was recording tracks, like, every day, with five or six people on the same track. That was the first thing that really gripped Preston in any kind of way that was relevant to me.

It sounds amazing.

The people that I was doing it with are still really good mates of mine. I was the only one to leave Preston. Talking now to these people who don’t have any hand in “creative work” at all – a lot of them are bricklayers, gardeners or traders – they say: “That was the sickest time we had, wannit?” And, yeah, it was mad. It was fuelled with all the same things that London had. People beefing from certain estates onto another estate. People would clash in a really tiny space in this estate called Brookfield and there would be hundreds of kids going out there to watch.

I think there are a few YouTube videos of these clashes from back in the day and they look like the worst [quality] videos ever. One is this kid called Lil P; one of his freestyles ended up on BTEC Grime. He’s MCing outside of this guy’s flat on this estate and the guy comes out with his cane halfway through and goes: “Do you mind fucking off?” Everyone was [thinking] it was a big joke, but that was literally the culture that informed us on what we’re doing today.

You’ve been based in Manchester, 27 miles from Preston, for a few years. Which parts of the city inspire you as a musician?

Manchester is a super resourceful place in terms of actually gathering sonics, like field recording stuff. There’s sound constantly coming from Manchester. There’s a track on our new project [with Space Afrika] which has this violin. I literally was walking through Piccadilly Gardens and I stopped for a couple minutes just to record this thing. You won’t get that in Preston! And, yeah, it is a really, really loud place, Manchester. I remember coming back from Berlin and being on the plane. I was with a couple friends, everyone was sad to be coming home, all that kind of thing. No one was really talking and the plane was dead silent. The airport was super quiet. Then we got on the train back to Manchester Piccadilly and I just remember as soon as the doors opened being like: “Fucking hell!”

I felt like a physical presence of how actually fucking loud it was! I think Man United had been playing so there was loads of football fans there. But it was like: fuck me, it wasn’t this loud in Berlin.

What about the area around The White Hotel?

I used to work at The White Hotel. I’d walk back from there whenever I finished, sometimes it could be nine in the morning. You’ve been in this pressure box of pure noise and lights, on an absolute sensory overload. Then you’re walking back through Cheetham Hill when it’s sleeping and there’s nobody there. It’s like you get this free pass, to just go wherever you want, and everything is really neutral for an hour or two. Those bits are like walking through the outer edges and little forays where things are still more forgotten – where things probably resemble what Preston’s like a bit more.

Are you pleased that you stayed in Lancashire long enough for it to shape you as a musician? Because once you get into a city like Manchester or London, you might find yourself going along with what other people are doing.

Kind of. I’ve always been really cynical. When I was younger, I thrived on being hard done by. I always really want to represent that through and through. It’s pretty much the basis of everything I do, to be honest.

Around 2020, a scene formed that included you, Blackhaine and Space Afrika. Do Mancs feel different to people from Preston, in attitude or outlook?

I think the Mancs are like… they’re just Mancs, innit? They have this unnerving confidence all the time. Such faith in everything they do. And there’s this chip on the shoulder, which you definitely need. I think that will carry you a long way. The Prestonian mentality doesn’t really have that. It’s just super cynical about things. Manchester is known as the rainy city, but Preston’s got the most rainfall in England, statistically. But we’ll get there, whether it’s working through spite or something like that. I’ll always work harder to defeat those shortfalls.

So, yeah, there is a stark difference [between us and Mancs]. When you see everyone in the room together, you can see there is a difference. Meeting that lot, I was really shocked by the confidence. I had to borrow so much of my performance style from watching them. I probably work harder than the lot of them when it comes to the music stuff. I’m doing a lot of the work behind the scenes, I’m mixing everyone’s records and producing all the records. That graft is a real Preston thing.

It’s just that underdog thing again. But any shortcomings I’ve got, I’ll just work a little bit harder.

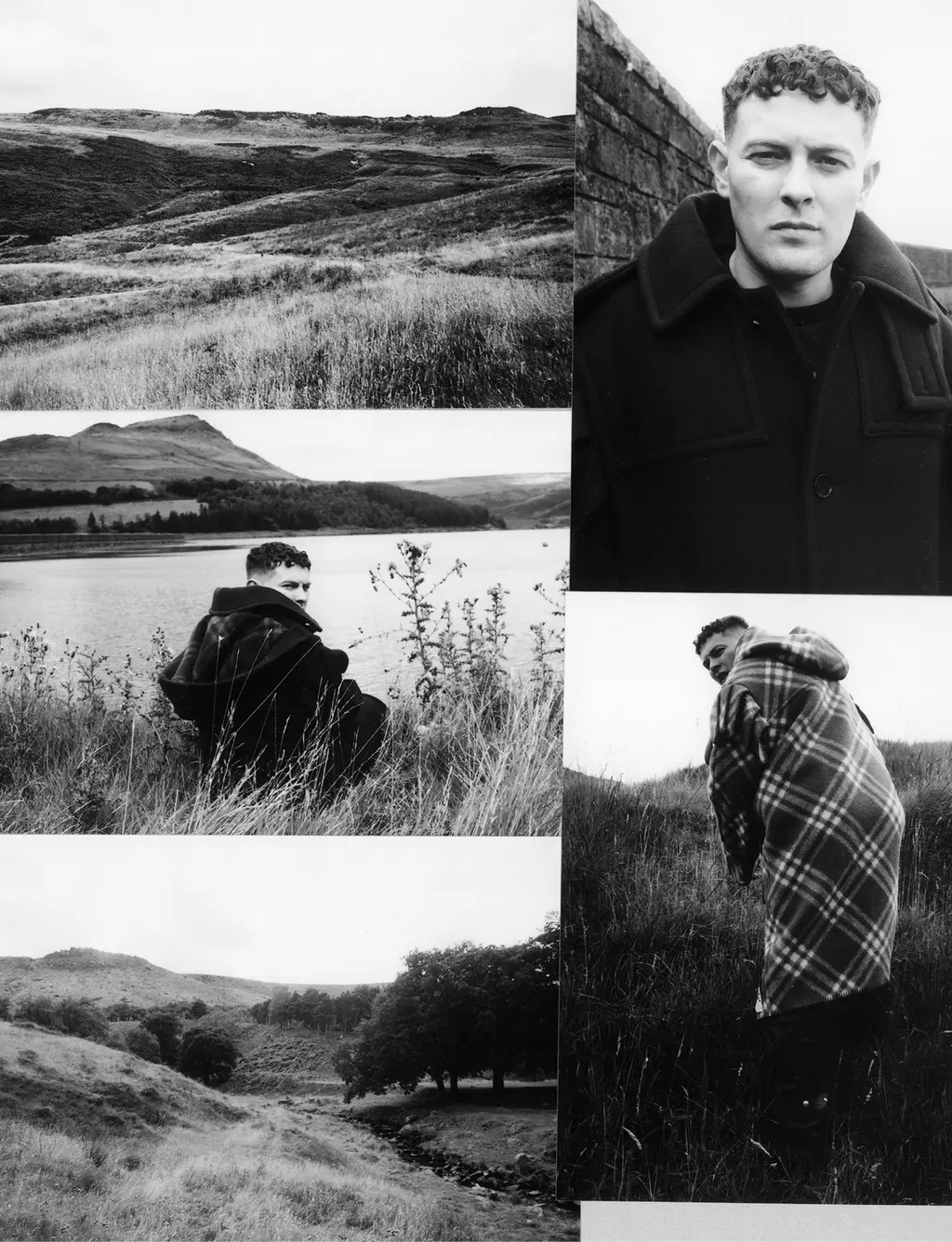

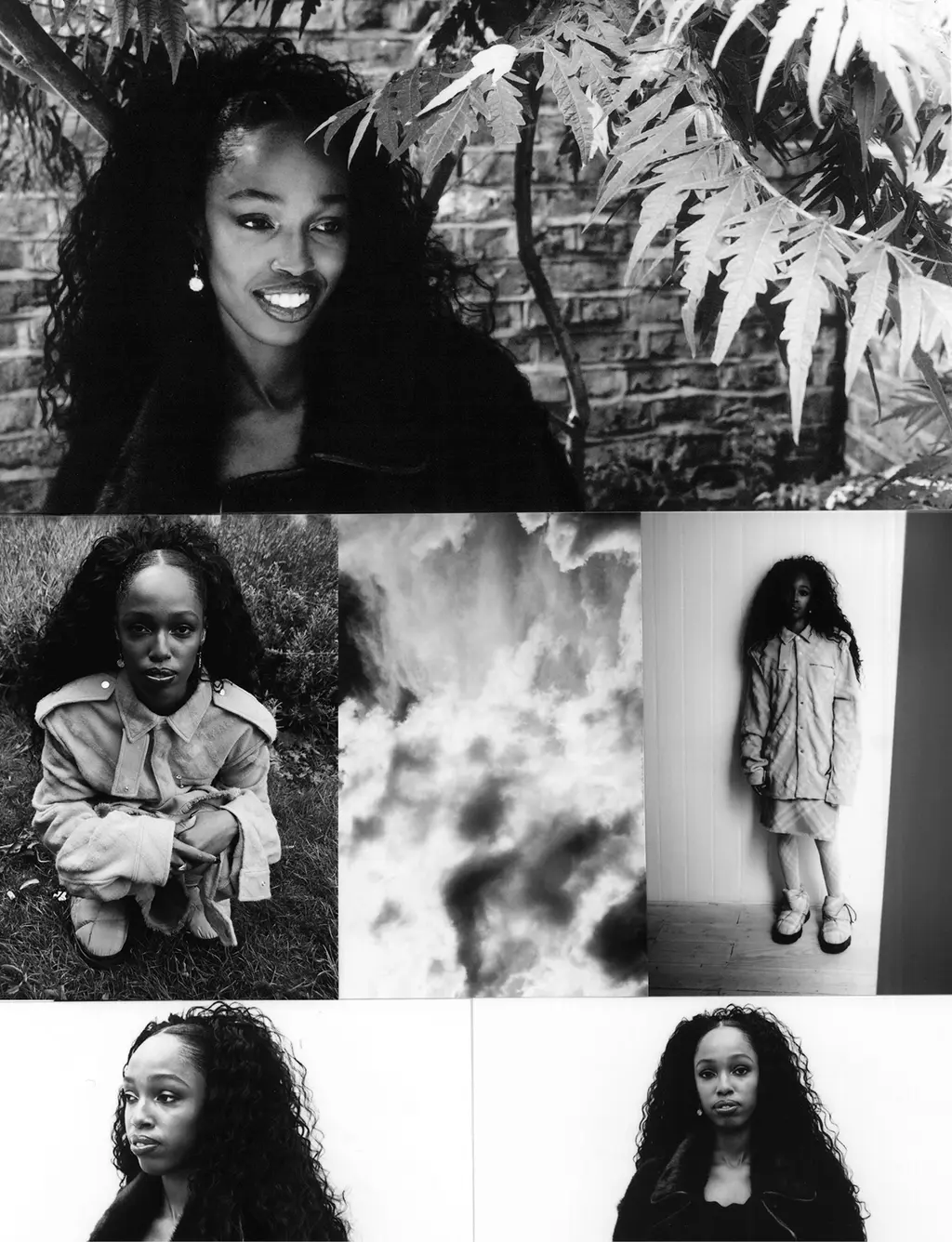

GEORGE RILEY

George wears all clothing BURBERRY

George Riley was born and raised in Shepherd’s Bush, West London, where she still lives. She bonded with her mum over Craig David and Sade, but music is in her DNA – her dad Mykaell played with legendary Birmingham reggae band Steel Pulse. At one point, Riley felt pressured to pursue academia instead of her true passion. But the soulful singer, 26, always felt more at home among London’s community of young, open-minded and genre-agnostic artists. Her collaborators have ranged from Vegyn and London jazz scene stalwart Joe-Armon Jones to Hudson Mohawke and Manchester rave producer/DJ Anz. George’s sound has been shaped by her lifelong love of jazz, the thrills of underage clubbing in the city and Notting Hill Carnival’s earth-shaking sound systems.

“I’ve been going to Notting Hill Carnival every year since I was a baby. I’ve always felt so at home in that music”

GEORGE RILEY

George wears all clothing BURBERRY

George wears all clothing BURBERRY

Shepherd’s Bush: what’s it like?

It’s very eclectic and it’s every kind of person. It’s got that rich history of being one of the first places Caribbean people settled in the UK. So that’s cool, there’s still that legacy. But obviously, it’s West London, and it’s extremely gentrified. Even in the last 10 years, it’s changed a lot. But I still love it.

You’re close to Notting Hill. How big has Carnival been in your life?

I’ve been going to Carnival since I was a baby – I’ve literally been every single year! It’s my favourite weekend of the whole year. I think also, not growing up with the Jamaican side of my family, I was a bit disconnected. Getting to go every year, that was my connection to it. I always felt so at home in that music, and just being among loads of people dancing. I love to dance. I love bass. I love to feel the pulse of the bassline.

How did London’s club culture shape you as a musician?

When I was a teenager, I made some friends who were musicians and wanted to go out to raves. I loved it. It was such an awakening. I remember being at the decks and being like, “Let me sing over this!”, and they’d be like, “No, go away!”

Singing over electronic music and dance music has been something that I’ve been around and wanted to do for such a long time. And I’ve been wanting to make music for that space as well, because I always felt so free. That was a big part of my growing up. That period is such chaos and so many bad decisions. But so much fun.

You left London to study at Leeds. How did that move shape your musical community?

I did philosophy and politics. One of the reasons I went there was because they had music college, and I had friends who were going to study music. I was like: great, I can do my academic thing, then I can make friends with the music people.

My grandpa loves jazz and he used to be a ballroom dancer, so he’s always encouraged me loads. Also, a big part of me growing up as a teenager was getting into jazz vocalists.

But when I got to Leeds, it was very much a case of [puts on serious muso voice]: “We’re on the jazz course – only for jazzists.” I felt like the vibe was a little bit unwelcoming. It was a little bit cold. Which was a shame for me.

How did you deal with that?

That time was about discovering lots of different things that I didn’t want to do. Because of my voice or the way that I look, I guess so far my journey has been more of an alternative route. I wanted to do something different, something that’s interesting to me.

So, I was coming back to London a lot. That’s when I met [producer] Oliver Palfreyman, who I made my first mixtape with. I was spending a lot of time in South London, and that was such a formative time for me because I was around a lot of musicians that I really respected. There was the jazz scene in South London that was going on at the time. It was all about creating and having fun, with no pressure about success or releasing – just making music and being part of the community.

How do you feel about the London music scene now?

London can feel really competitive. There’s this sense of individualism. There’s also an obsession with youth culture and being young, which can feel isolating for some people. And there’s a lot of scary people! On the other hand, I’m in a spot where I know who my friends are in the industry and I’m OK with that. So, yeah, I’m feeling optimistic.

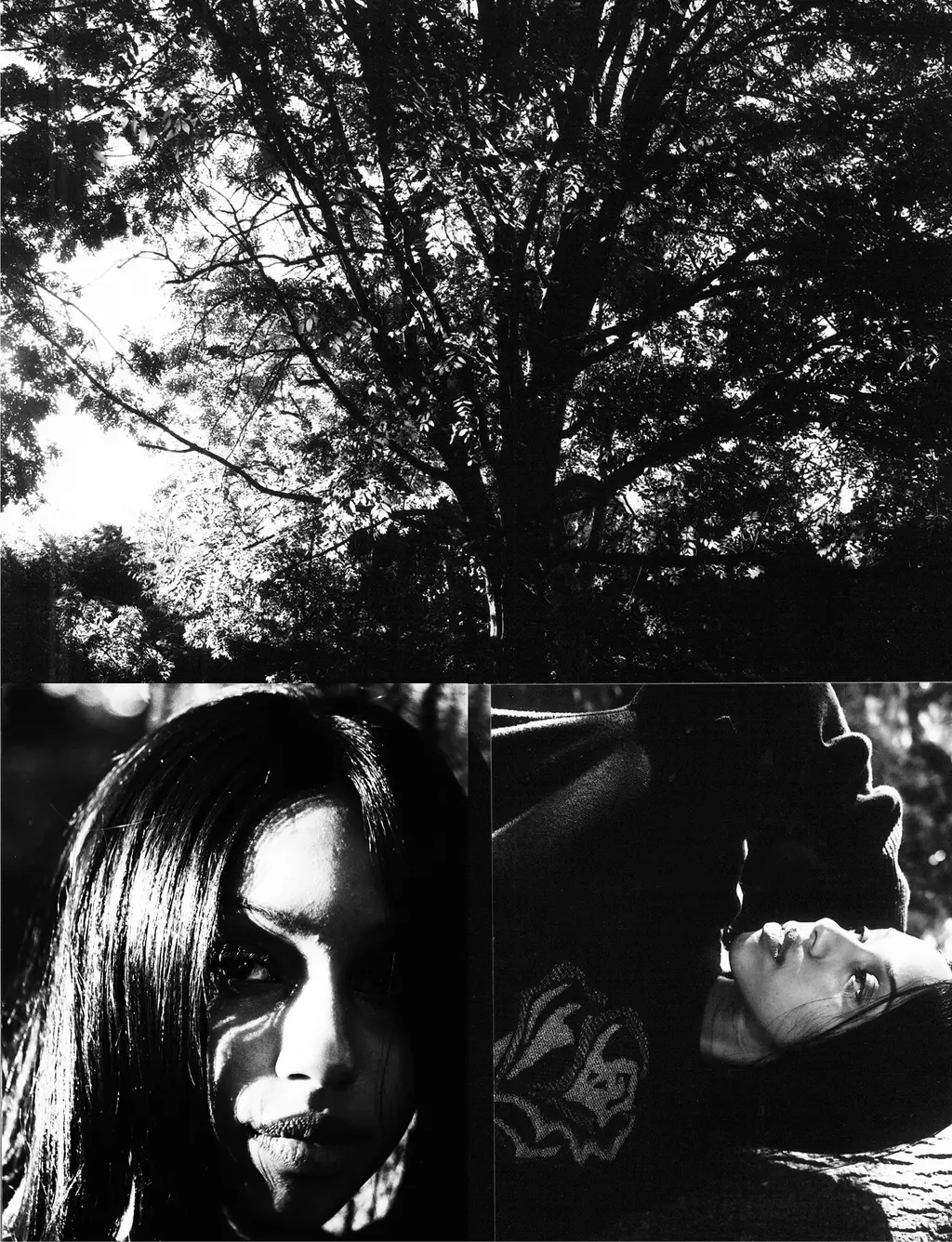

LCY

LCY wears all clothing BURBERRY

The best Bristolian music usually blends two key ingredients: sound system-indebted bass and West Country weirdness. Late ’70s/early ’80s bands such as The Pop Group and Maximum Joy incorporated dub bass into their fractured post-punk styles. Trip-hop legends Massive Attack and Tricky – both spawned from the Wild Bunch sound system crew – mutated NYC hip-hop with eerie eccentricity, soundtracking stoned nocturnal walks through the city’s graffiti-smothered streets. More recently, Bristol has nurtured a new underground of bass freaks, with labels Young Echo, Sector 7 and Bandulu encouraging producers to mutate the formulae of grime and dubstep. All these waves have inspired LCY.

Now based in London, the 26-year-old has earned a reputation as a dextrous club DJ, applying their expertise in chest-rattling bass to radically experimental productions exploring gender and religion.

“Bristol has a history of mixing up genres, and that’s how we’ve got some of our biggest acts. When you mix genres, immediately it sounds different and exciting”

LCY

LCY wears all clothing BURBERRY

LCY wears all clothing BURBERRY

People always say that Bristolians love bass. It’s true, isn’t it?

Absolutely. I think there’s more respect put on it. Sound systems are more normalised. Everyone knows someone that has a system, has an uncle that owns a system – or at least has a system they go to at St Pauls Carnival [in the city].

What kind of music were you raving to growing up?

The first club night I ever went to was a dub night, at the Black Swan. They had two systems on either side of the wall and it was kind of dingy. It changed my view on bass as a whole, feeling it all the way through your body. And then I used to break into house raves. There was also jungle, drum ’n’ bass, reggae, dub, dubstep and dancehall. Basically, all genres!

Are there any personality traits specific to Bristolians?

The stereotype of people being more relaxed and being more friendly – I think that’s true. Everyone I know who was born in Bristol has a heart of gold. And they’re generally more accepting. We’re now known worldwide for protesting, which is definitely a true statement. It’s quite anti-capitalist and green. People regard us as hippies, and I would regard myself as a bit of a hippie in that respect. I do think that there’s this idea that life is golden in Bristol. But growing up there, it wasn’t always the case.

There’s also the stereotypes about a slow pace of life. They say people walk a bit slow and smoke and, like, do loads of drugs! I don’t know if that’s true for everyone, but I definitely experienced that growing up.

Has the city’s reputation for radical politics informed your worldview?

I would say it has a slightly more anti-capitalist, anti-government standpoint than a lot of places I’ve been. I feel like the Caribbean community deserves a lot more credit for [its] resistance. In 1980, for example, there were the St Pauls riots [against police harassment of the Black community] and I think this has led into this culture of: “We are going to resist government actions and we are going to stand up against what’s wrong.”

Kids there get a slightly more liberal upbringing. That’s super positive. But I still feel there’s a lot more Bristol could do on certain topics, like racism, and I don’t think it supports the working class or mental health [issues] enough.

Is there an eccentricity to Bristol music? A lot of artists have taken bass-heavy music and done something strange with it.

I think so. The city has a history of mixing up genres, and that’s how we’ve got some of our biggest acts. When you mix genres, immediately it sounds different and exciting. But I also think it’s a creative city and that creativity is more encouraged. An eccentricity, yeah – I like that.

What motivated you to move to London, and how did you feel when you got there?

I moved six years ago. When I was in Bristol, my plan was always to escape to London. I had this panic. I didn’t have the best background, so I was just, like, I need to get out of the city. London has a lot more opportunities. It benefited me in terms of meeting people and being able to put my music out there.

It also made me respect my own city more. I’d tried to escape Bristol for so long that I’d kind of viewed it in a negative light. But actually when I left I was like, oh, shit, no – actually, it’s fantastic and the people are fucking amazing. And I’m really grateful for that upbringing that I had, even if it had its turbulence.

Your music sounds particularly urban, but there’s a lot of open space in it. Do you spend time in more rural spaces?

Because I grew up in the city, I always found outdoor spaces quite scary. But I’ve been taking quite a lot of acid over the last few years and I’m finding it’s helping me appreciate nature a lot more. I’ve also been exposed to queer ecology and contemporary and performance art, largely by my friend Deen Atger and their residency programme @Disturbance at Ugly Duck. It’s opened my mindset.

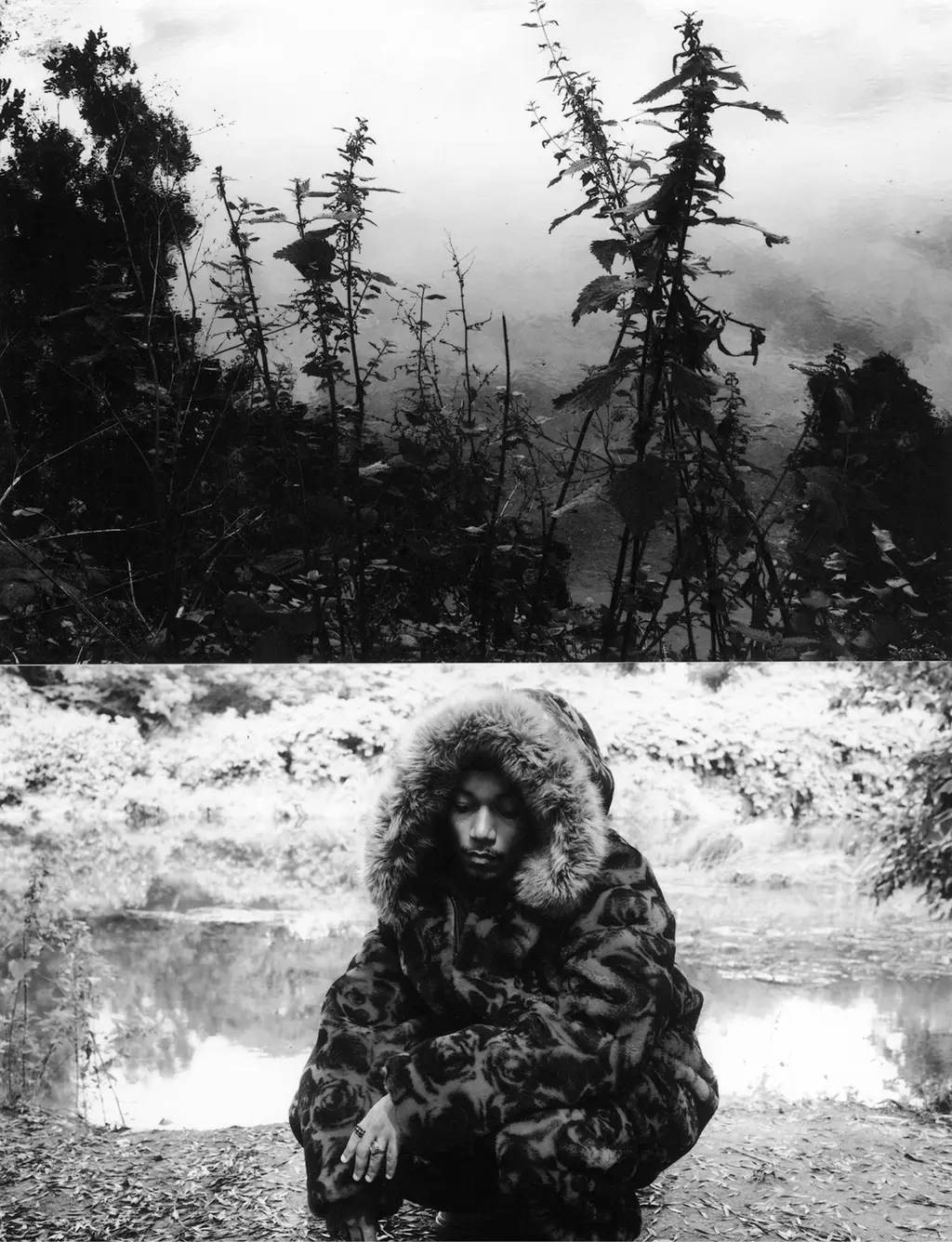

WESLEY JOSEPH

Wesley wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

On his stunning 2023 single Monsoon, Wesley Joseph raps from the perspective of his 17-year-old self, daydreaming of bigger things while growing up in Walsall, the West Midlands town a 20-minute drive from Birmingham. He feels constricted, confused and depressed. But in the second verse – written from the viewpoint of Wesley’s current self – he recognises that Walsall made him the artist he is today. As the 27-year-old spits with determination and fire: “I feel purpose and soul, feel it burn inside me.”

Since releasing his debut solo single Friends in 2020, Wesley has evolved from an ambitious bedroom artist to a gifted singer, rapper, producer and video director. He merges futuristic R&B, psychedelic funk and neo-soul, and can effortlessly fluctuate between buttery falsetto and razor-sharp raps. He dreamed up his vision as a teenager alongside the Walsall crew OG Horse, which also included musicians Jorja Smith and Otis Wongasm. Although the collective is disbanded, its members remain close friends and collaborators.

“At home I would hear a lot of soul, reggae, dub, funk. My dad’s a collector of predominantly Black music. That’s definitely in my creative DNA now”

WESLEY JOSEPH

Wesley wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

Wesley wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

What genres were you raised on?

At home I would hear a lot of soul, reggae, dub, funk. My dad’s a collector of predominantly Black music. He just has a mad archive. So I was introduced to that music as soon as I entered the house as a baby. That’s definitely in my creative DNA now, in my ear for harmony, my chord preferences. I love bridges. I love backing vocals. And then when I get into rap and dance music, my dad’s the type of person to be like, “this is the original sample for that”, and show me a vinyl. Then he’d be like: “And this is the person who inspired that person.” And then he’d pull out another vinyl.

And he was in a band, right?

He was in a band with Jorja Smith’s dad in Walsall. My dad played drums and percussion. I think he was doing sampling stuff. He was the rhythm guy. Jorja’s dad was the lead singer.

It must be emotional for them, to see how their kids have grown up to be successful musicians who’ve collaborated with each other.

It’s beautiful. Jorja’s parents came to my last London show at Koko. They’re all tight.

What was going on in Walsall musically when you were growing up?

It was an era where everyone was on the back of the school bus and local grime was popping. Someone would be like, “this is that tune that my brother made”, and then that would go around locally on people’s phones. This was before the iPhone. Sony Ericsson, Nokia, Walkman, Motorola Flip.

Do you ever go back to Walsall to get inspired?

I went back recently to see my grandparents and get my hair cut by my old barber. To have a walk around, have some peace of mind, get some perspective, because I’m writing my [debut] album, and life has been very intense. In terms of that true perspective and speaking on things that really fit at the core of who I am, I needed to go back home. I’m probably going to go back home again soon, too.

Any personality traits specific to people from the West Midlands?

For sure. I’d say everyone is authentic and unapologetically themselves. It’s more honest. I would also say everyone is just hilarious. That’s why I’ll always be humble, grounded. I’m never going to believe my own sauce. That’s because I’m from where I’m from.

What was it like coming up as an artist in a small town?

It was very liberating for me being from a place that isn’t really attached to anything else. That allowed me to just freely express in a way that was untainted and felt quite pure.

You weren’t surrounded by careerists, or people who are thinking of music in terms of marketing?

I didn’t understand the concept of a manager, I didn’t understand the concept of an industry. I didn’t understand the idea of someone paying for a video, or any of that stuff. You come to London and I speak to certain people and they’ll be like, “Yeah, I had a manager when I was 16.” That didn’t make sense to me or any of us [in Walsall]. We would still be marketing, but we’d do it in the most guerilla style ever, just on the internet. Doing mad shit to get people to hear what we were doing.

Do you feel motivated by being the underdog?

My whole thing is being the underdog at all times. My mentality is shaped around being the underdog. That’s why I’m always punching above my weight. That’s why I’m always trying to go as hard, or harder, than what I can see around me. That’s why I’m totally OK with not getting the flowers. Because I know they’ll come later.

When you’re on the outside coming here [to London], you don’t know anyone. And a lot of this stuff, especially in London, is nepotism. Everyone knows each other. It’s a club thing where everyone’s connected. You just come here and the only thing you have is what you make and your value as an artist.

There’s something I like about that. It’s not something that pisses me off, although it used to when I was younger. I like not knowing anyone in the room, but then knowing that people know the art, even though I wasn’t part of the club.

That’s not to say I don’t like socialising, I’ve made a lot of amazing friends. But I like the feeling of proving myself against the odds. I believe in myself. It’s just a matter of time with this. It keeps me on my feet and keeps me feeling alive.

JOHN GLACIER

John wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

It’s rare for a musician to sound truly original these days, but John Glacier is unique. The Hackney native’s style sits somewhere between braggadocious rap and delicate spoken word, and she can summon both the queasy euphoria of a messy night out and the profound beauty of her family’s Jamaican homeland within the same vignette.

On her 2021 debut album SHILOH: Lost for Words, John carved out a distinctive style, pairing her intimate poetry with gooey beats predominantly produced by Vegyn, who released it via his Plz Make It Ruins imprint, and she’s evolving her sound for an upcoming project on the Young label.

Although she stands on her own in the landscape of new London music, John’s gravitated to collaborators who also swim against the tide of commercial UK rap, such as Jadasea, Ragz Originale and Dean Blunt’s Babyfather project. Despite having a buzz both in music and fashion, her gloriously chaotic Instagram activity portrays an artist who’s keeping it real. On any given day, she might post glossy magazine shoots, fashion show bathroom selfies or dancehall music videos, memes and photos of the ducks swimming in the canal at Hackney Wick.

“Storytelling is massive in Jamaican culture. A lot of the history is not typically written down, it’s just passed-down information. That’s definitely influenced me a lot”

JOHN GLACIER

John wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

John wears all clothing and shoes BURBERRY

What are your early memories of hearing music around Hackney?

My dad used to have a Caribbean food shop. Throughout that shop, there was consistent music, usually Jamaican music, blaring out the whole day. On that same road, there was the Saxon Sounds record shop. They also had a massive sound system, they were a set of sound system DJs from Jamaica. They used to buy from our family, so we’d go there as well. They’d do really cool Jamaican-style badges. You know the ones that you iron onto your clothes? I used to go in there just for those and patch up my clothes.

Who were the local artists you were into as you got older?

The rapper Rimzee. Now, he’s made a big name for himself but before that – maybe 2010, or maybe a bit earlier – he was massive in Hackney. Him and Mash Town [collective] specifically were doing big things in Hackney. They were more road rap. But in terms of grime, around the same time, Ghetts and Kano had a show at the Hackney Empire that I went to. The Hackney Empire, they actually put on decent events. There was good stuff going on in East London, musically.

How has Jamaica inspired your music?

Heavily. Because storytelling is massive in our culture. Usually oral storytelling. A lot of the history is not typically written down, it’s just passed-down information. Storytelling is massive over there. That’s definitely influenced me a lot.

What areas of Jamaica do you like to visit?

I’ve got family in the city, but I prefer the countryside. Where we live is in the mountains, in what they call Cockpit Country.

You have to drive up a shitload of valleys to get to our house. But when you get up there… to me, it is like paradise. It’s a surreal environment. It’s just tropical trees, fruits, mountains. Because we’re so high up where we are, sometimes you’ll see like the clouds beneath the mountain.

It’s peaceful, but also you have your bars and a lot of street parties out there. They have car sound systems, these cars with crazy LED lights, but kitted out just for sound system purposes.

Do you write lyrics when you go there?

I haven’t been since the pandemic but whenever I go there, I write a lot. You have a lot of peace out there, so your brain feels clearer. My uncle’s got a farm. We just chill.

Then there’s a place called Luminous Lagoon, where the water naturally glows in the dark. So we’ve got all of these crazy spots to just chill by, stuff you wouldn’t see over here. And so there are emotions that you wouldn’t feel over here either, which gives me a broader scope to write.

How do you feel when you get off the flight in London after being in Jamaica?

Honestly, I find it depressing! Because every time I’ve come back to London it’s been raining here. But then, after a few days, I’m happy to see people and whatnot. London and I have a love-hate relationship. I love what it has to offer and hate what it sometimes has to dish out. My favourite things about London are the communities it hosts. I love the nightlife, the ducks and the diversity.

How has Hackney shaped who you are?

Hackney people, we’re nice, but we have our limits. One thing I find interesting when I’m navigating this industry is that a lot of these people don’t have any manners. And the way they interact isn’t the way I was raised to interact with people. In Hackney, we have a certain way of interacting with people and we have respect for others.

What to you is exciting about the London music scene in 2023?

I feel like the London scene has sick stuff. We’ve got Tora‑i, we’ve got Celeste, there’s BXKS. Women in music in London right now, they’re going crazy with it.

CREDITS

HAIR FOR JOHN AND GEORGE Taiba Akhuetie at Keash MAKE-UP FOR JOHN AND GEORGE Luz Giraldo PRODUCER Louise Nindi PHOTO ASSISTANT Max Granger STYLIST’S ASSISTANTS Borys Korban and Hollie Williamson ASSISTANT PRODUCER Sami Ambrose