Welcome to Planet Yeat

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS and T-shirt, trousers, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat has topped the US album chart thanks to the rabid young fanbase of his ecstasy-fuelled mutant rage rap. But is his bizarro persona all an act? THE FACE joins him on a tipsy adventure in Paris to find out.

Music

By: Jon Rafman and Moni Haworth

Styling: Danny Reed

Words: Kieran Press-Reynolds

Taken from the winter 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

We’re in the Grand Palais, Paris’ historic exhibition hall: a cavernous space with an arching roof and glass skylights that feel like a train station in a fairy tale. It’s VIP day at Art Basel Paris, mostly high-end collectors, and the room is filled with some of the most expensive fine art pieces in the world. Julie Mehretu’s gorgeously grey painting Insile, for example, sells for $9.5 million later that afternoon. Dainty, bespectacled Parisians shuffle in clusters; prospective buyers in natty blazers huddle in corners. Then, there’s Yeat. Flanked by bodyguards, the rapper from Fullerton, California, drifts languidly through the maze of installations, clad in a long, black Vetements jacket, silver skull chain, black pants and a black Kangol beret.

Arguably the most bizarro breakout rapper of the 2020s, today the 24-year-old Romanian-Mexican American looks like an arthouse vampire, the Dr. Doofenshmirtz cartoon supervillain of the post-SoundCloud rap set. Every now and then, he stops to snap a phone photo of a painting of a withered body or a sculpture that looks like mutilated limbs. “This one soothes me,” he says of a piece with swirling blue brushstrokes.

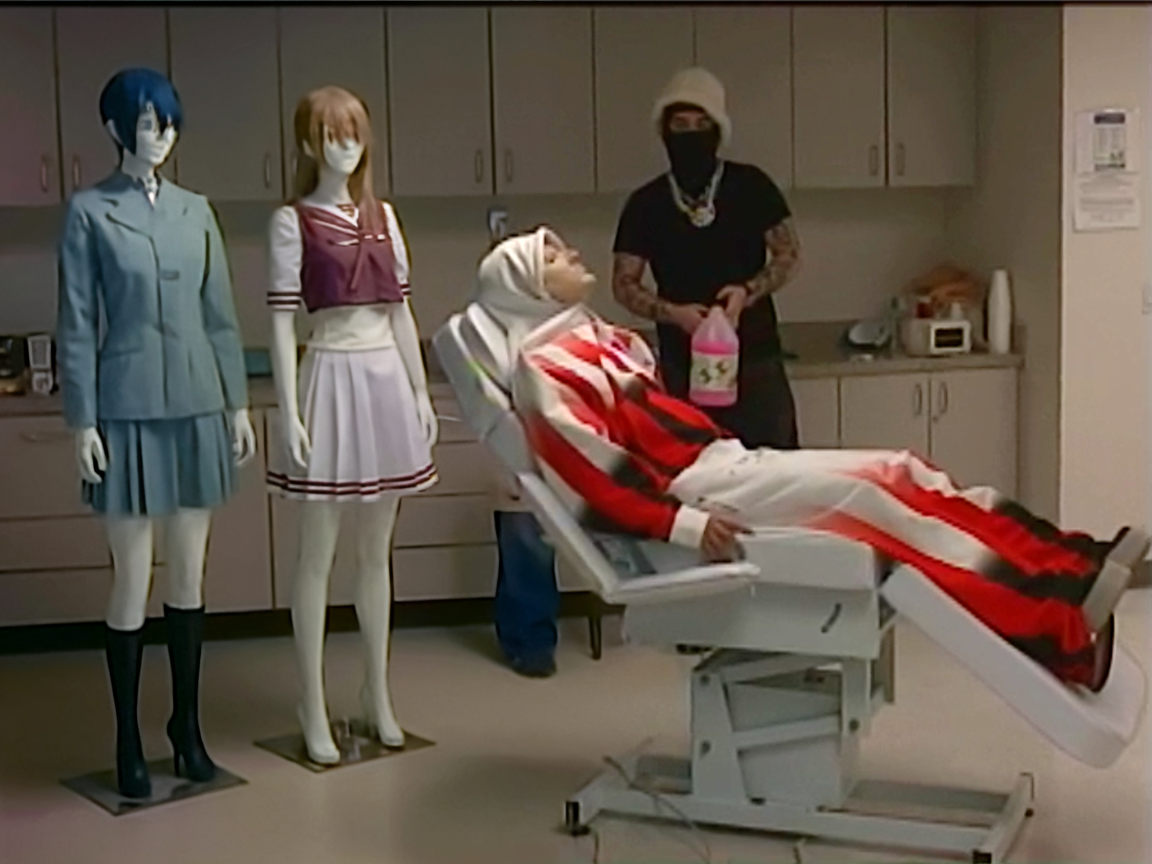

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava, jewellery and shoes talent’s own

Yeat, born Noah Olivier Smith, is in Paris for the penultimate stop of his Eurolyfe tour, two days before he drops his fifth album Lyfestyle. Our meeting coincides with the emergence of the rare Hunter’s supermoon, a serendipitous coincidence because of how otherworldly Yeat’s music sounds. Everything about his style radiates alien: his psychotic gurgles, his rabid squirrel ad-libs, his taste for nuclear fission beats. Then there are his invented words (“twizzy”, “kranky”, “shmooktober”) and his obsession with putting umlauts on the ë’s in many of his songs.

While haters moan about his slurry of babbling vocals, Yeat is attached to the same mumbilical cord as Future, Young Thug and Playboi Carti. He just reforms their genetics into a whole new family tree of warbling weirdos. In a single song, he sounds like a Martian dictator, a Martian dictator’s Venusian wife, a Martian dictator’s infant crying while his mum cuts the cord, and practically the whole extended bloodline. Often, he’ll harmonise with impressionistic warbles in the background, doing Migos’ fragmentary trio-layering as a one-man choir.

Critics have argued that Yeat’s music is vacant of both swag and meaningful subjectivity: he’s not political, he doesn’t rap stories; his entire shtick is part-cosplay. But at his best, he’s the raw id of our musical trend economy, burning up the algo ether with silly nothings. So, yeah, Yeat’s music is zany, and if you’re the kind of ageing rap fan who misses the days when lyrics were comprehensible, you’ll probably hate it. But evidently, millions of American kids love it – Lyfestyle reached #1 on the US Billboard 200 chart – and he has rap heavyweights behind him, including collaborators Drake, Future, Lil Durk and Young Thug.

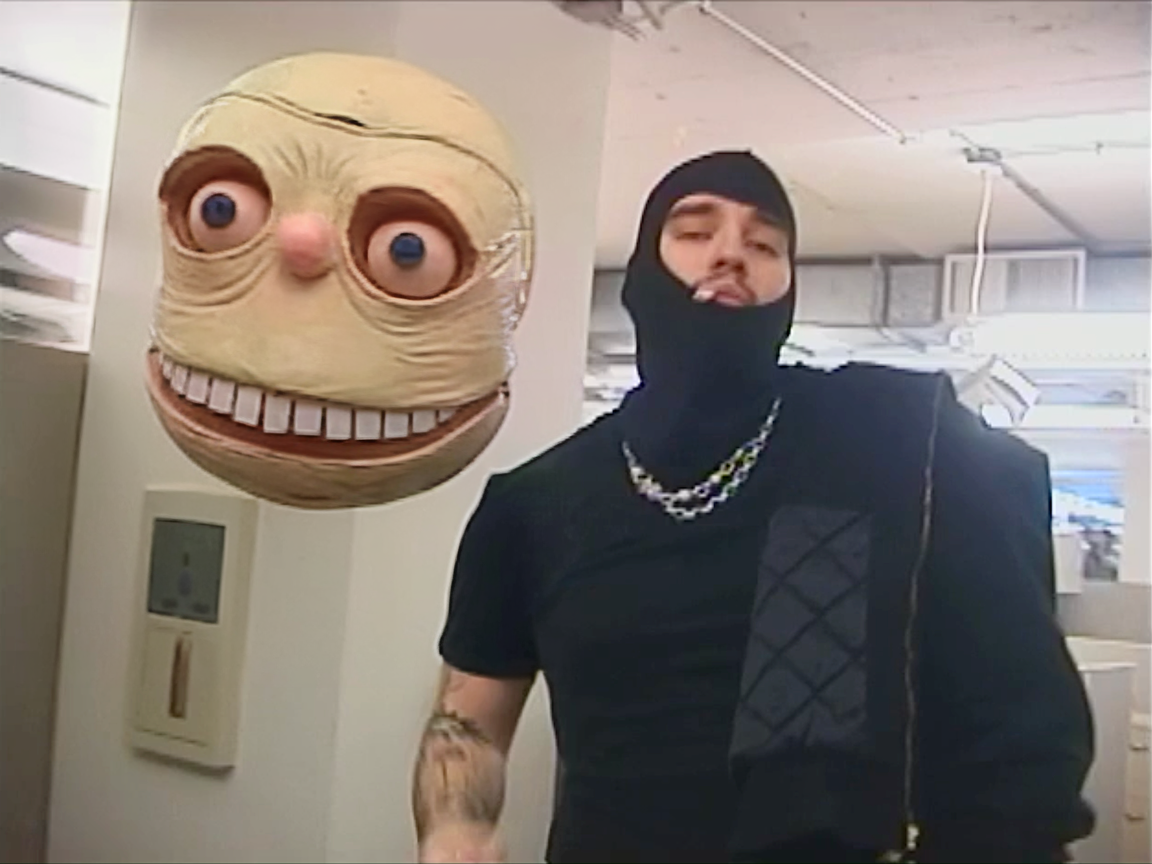

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS, T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own and mask stylist’s own

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS and T‑shirt, trousers, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS, T‑shirt and jewellery talent’s own and mask stylist’s own

Yeat has maintained the image of a press-shy, balaclava-clad eccentric by only granting a handful of interviews throughout his career, and during most of them he’s shrugged off questions with deadpan humour (during a chat with YouTube channel Dripped TV, he insisted that he eats 14 bowls of cereal a day). As megastars pump out GRWM vlogs and relatable-by-rote Insta dumps, Yeat does the opposite, rarely posting to his 3.8 million Insta followers beyond sporadic spurts of cryptic nonsense. It’s a purposefully cultivated enigma that has fans so feverish, they attempt to decode every lyrical and social snippet and speculate about the minutiae of his life, even going as far as to theorise about what drugs he might be taking based on his vocal timbre.

Yeat wears T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS, T‑shirt and jewellery talent’s own and mask stylist’s own

After Art Basel, we have dinner on a sun-dappled outdoor patio at the luxury Hotel Costes, surrounded by Parisians in white button-ups and waitresses ferrying trays. As he downs champagne and escargot while engaging in discourse about art, black sunglasses cloaking his eyes and matching his dark hedge of chin beard, it’s easy to forget I’m here with a rapper famous for outrageous lines such as, “Osama Bin Laden my bro” and the all-time heater, “Told that bitch to Bob the Build that booty if she really want one”. Yeat seems like two people at once, constantly code-switching his persona between extraterrestrial and Noah the Nobody.

One moment, he’s showing me his lock screen, a damn Minions meme (for the uninitiated, he made a viral song for the Minions movie). The next, he’s telling me with grave conviction that he was the victim of a terrifying alien visitation when he was a child. “They didn’t say anything,” Yeat recalls of his encounter. “They put a light up to my face and just left. I had my blanket over my face because I didn’t wanna look at them, I was too scared – I was like, fuck this shit. It looked like they had a lantern that was so bright it shined through the blanket. That’s basically my first memory ever. I think they maybe wiped my memory.”

Currently, Yeat splits his time between Los Angeles and Oregon, where he went to high school and now owns a house with a 3.5‑acre compound. It serves as both a studio and a chilling zone, as well as a place to store his trophies (awarded for his gargantuan streaming numbers) and his 260 guns. That fearsome arsenal is part of a doomsday supply that also includes “gas masks, nuclear fallout pills – so you don’t get cancer when the nuke hits – food rations for years, about 300,000 bullets, armour, helmet, night vision, thermal…” He also says he’s spent $1.5 million on a worst-case-scenario cache of weapons and ammo. I’m a little startled, but, as he forks garlicky molluscs from their shells, Yeat makes like his survivalist bunker is nothing. “I like that to be my place where, if shit goes down, I’m good,” he says.

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt and hat talent’s own

Yeat wears T‑shirt, trousers, balaclava, sunglasses, jewellery and shoes talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket ACNE STUDIOS, T‑shirt and jewellery talent’s own and mask and mouth guard stylist’s own

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own opposite (background): Jester wears hoodie, trousers and stole ANONYMOUS CLUB

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own opposite (background): Jester wears hoodie, trousers and stole ANONYMOUS CLUB

A key to understanding Yeat is to talk about Zack Bia, the 28-year-old DJ, record executive and It boy who’s been blessed with a couple of flattering GQ profiles and whose name is a fixture on every schmoozy industry party list. Zack signed Yeat to his Geffen sub-label Field Trip Recordings. He’s affable, generous and a highly skilled salesman. Last night, we were all supposed to dine together but Yeat had twisted his ankle while hanging with friends during his previous tour stop in the Netherlands, so he needed to convalesce. Instead, Zack took me out to eat and gave me a walking tour of the 8th arrondissement’s Yeat landmarks, from his favourite Chinese restaurant to a spot on the edge of Parc Monceau where the shadowy video for his song On tha linë was filmed two years ago.

The two have a keen sense of how interviews, when done sparingly, can add to the aura and spectacle around an artist. Like a carefully calibrated IV drip, just enough wild intrigue can make a cult star feel constantly fresh. But Yeat and Zack – who hangs close by during most of our conversations – also seem like twin tricksters, trying to make the interview as bizarre as possible for kicks. During our lunch, they riffed about making me hand over my phone so Yeat could change the password to a random 14-letter code, which I could only figure out through clues they’d give me during the day.

I was just glad they didn’t insist on conducting the interview over Morse code, which Yeat claims is his preferred mode of communication because it allows him to “speak with no emotion”. He says he sometimes responds to questions on phone calls with “yes” and “no” by clacking on a typewriter – he claims his friends have memorised the different sounds the “Y” and “N” keys make when he presses them.

He also claims he’s never seen a single movie or TV show in his life, though he would like to act. I lay a trap: “Whose work would you most like to act in?” He says Donald Glover’s, then teases that they may make a show together in the future. “I just finished the first season of Atlanta,” I say. “Amazing,” he nods, before self-correcting: “Heard of it.” He explains that Lyfestyle is so electric – maybe the most raucous, rave-crazy album he’s made – partly because he’s back, after an admittedly short period of abstinence, on a diet of decadence.

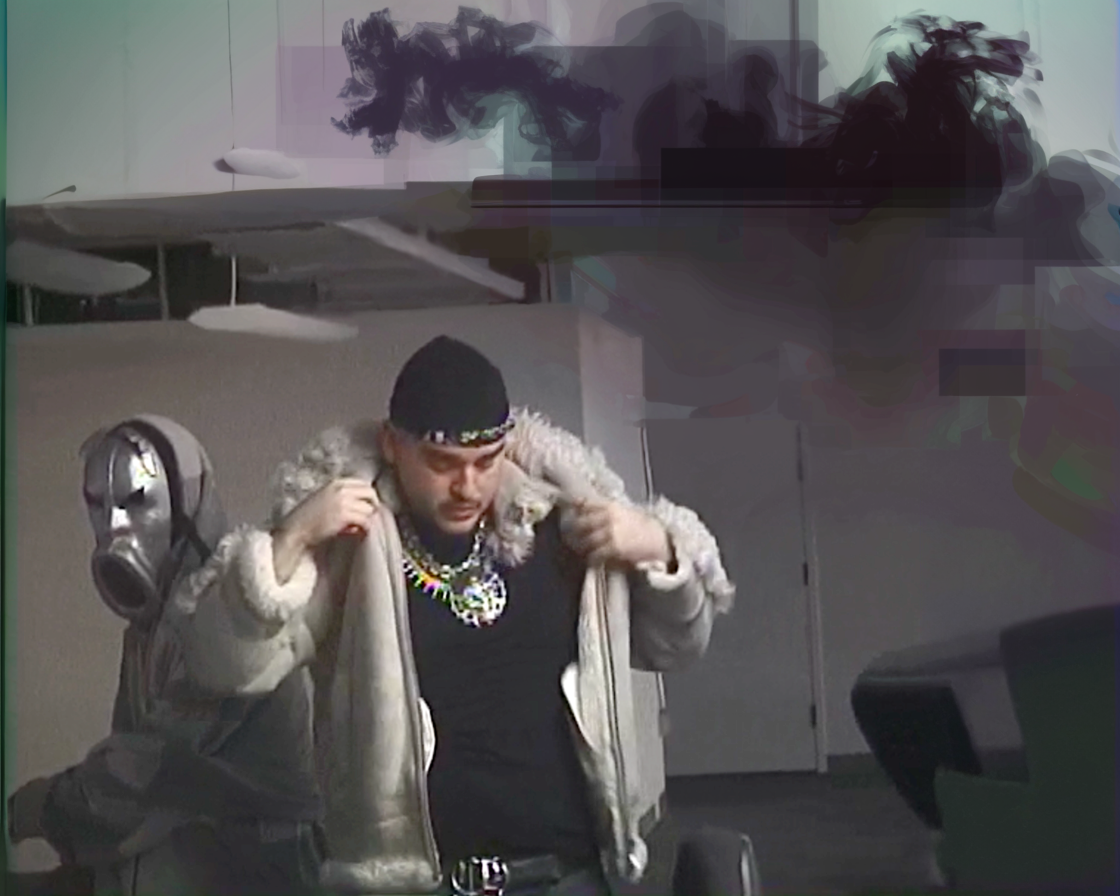

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

In a Complex interview two years ago, he said psychedelic drugs (acid in particular) opened up his mind when he started doing them in high school. Yeat was doing ecstasy while making his first album Up 2 Më (2021), whereas he says he was in “a perc era” for the creation of his 2023 album AftërLyfe. He was sober while making 2093 – the first of the two LPs he’s released this year – but for Lyfestyle he’s been “kind of back in that bag. Not X like that, but more turn-up bag, drinking, partying here and there… I’ll never lie in my music. If I’m geeking, I’m geeking.”

Some of Yeat’s songs have been genuinely worrying for a listener. There was the shivery swirl of 2021 track Lët ya know, in which he cried about feeling like he’s dying from ecstasy and warns that it could be his last song. In fact, he tells me he almost “died three times” making songs around that time – see also the bubbling lava pool of Always Alivë, released the same year. “I made 20 songs that night, just geeking in a closet. I’d probably been up nine or 10 days with no sleep,” he claims, saying he’d been consuming a cocktail of Adderall and ecstasy. He’s now sworn off opiates, because they’re “too slow, make me lazy and make things boring” and he’s getting back to a more turnt vibe. “You’ll hear it in this music, just by the choice of beats.”

Yeat wears T‑shirt, trousers, hat and jewellery talent’s own Jester (middleground) wears hoodie and trousers ANONYMOUS CLUB and shoes RICK OWENS

Yeat wears T‑shirt, trousers, hat and jewellery talent’s own Jester (middleground) wears hoodie and trousers ANONYMOUS CLUB and shoes RICK OWENS

Yeat wears T‑shirt, trousers, hat and jewellery talent’s own Jester (middleground) wears hoodie and trousers ANONYMOUS CLUB and shoes RICK OWENS

The bashing intensity of Lyfestyle is a shift from 2093, which was themed after a Blade Runner-esque dystopia and unfurled with cinematic instrumental passages. That project was the result of the rapper renting a vineyard in Oregon and erecting on the grounds something of a Yeat Summer Camp. Producers were flown in, he’d hold court every morning with instructions, then they’d spend the day churning out beats. For Lyfestyle, Yeat locked in with California beatmaker Synthetic, who co-produced most of the album, and who apparently helped Yeat sift through around 7,000 beats for the project.

The result: himbo rage rap with a new level of polish. Yeat threatens to burn his enemies like “shrimp on the barbie” amid the wicked thrum of On 1, which cranks the gain up at the end until everything starts clipping. He’s proudest of Gone 4 A Min, a synthy slither that could soundtrack an army of cyborgs slow-walking in Balenciaga. “Gone 4 A Min is the best song on the album, maybe the best song I’ve ever made,” he declares, slumping back in his white-cushioned chair. “Possibly. Top 100.”

Yeat wears jacket CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket and trousers CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat courteously refills my champagne glass. We pause to say cheers. Zack and Yeat tell me that if I don’t look them in the eyes while clinking glasses, it’s seven years of bad sex. Then Yeat lowers his dark sunglasses solemnly, like an executive about to deliver a layoff. “I’ve got two years left,” he laughs. Then he recounts a story about how he almost lost 35,000 songs on his laptop, because of course Yeat has 35,000 extra songs (plus 10,000 more on a hard drive). He was saved by his girlfriend Symone Ryley, who runs the LA clothing brand Sync by Symone (which Yeat has modelled for); she convinced him to back up his laptop right before it randomly died. “I would’ve been fucked, this whole album would’ve been fucked,” Yeat says, shaking his head.

He has so many songs because his process is as Adderall-fast as the music; he says he’s in a state of perpetual cooking, grinding on Lyfestyle as soon as 2093 came out in February. Yeat’s technique goes like this: get the beat. Run ad-libs. Freestyle. “I don’t write anything. I go 30 seconds of just freestyle and I’ll probably keep it. First go’s usually good.” Then he might lace the beat with sweet textures. He touts the beacon-bright leads he added to Orchestratë and They Tell Më, saying they tie the symphonies together. Taking out his iPhone calculator and plopping it next to his plate like a grandma trying to figure out the tip on a restaurant bill, he computes how long the album’s 22 tracks took to make cumulatively: about 287.5 minutes, averaging 12.5 minutes each.

As the meal goes on, I can feel Yeat warming up to me. Although much of our convo feels like I’m prompting a malfunctioning Zoltar machine, there are moments of surprising candour. He tells me that, one day, “at the right time”, he’d like to make a song with his dad, who was in an electronic folk band before he was born.

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T-shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

He seems at his happiest and most earnest when recalling his July show at the Beach, Please! festival in Romania, in front of 60,000 feverish fans. It was the first time he’d performed in his mum’s ancestral land. She accompanied him, along with his dad and brother. Locals recognised him everywhere; he recounted a particularly joyous moment when he got off a jetski on the beach and found dozens of kids just standing there waiting for him. “I took pictures with everybody,” he smiles, adding that the only phrases he knows in Romanian are “come here” and “I love you”.

By the end of the lunch, we’re all a bit rosy-cheeked. “A couple cups of Veuve got me sauced, I forgot I have a show today,” groans Yeat, calculating how many hours he has to sober up before tonight’s show. On the Mercedes-Benz ride back to the hotel, I listen as he and Zack brainstorm a music video idea. We pass the hulking columns of the La Madeleine church as Yeat imagines a scene where a concrete wall shatters and explodes to reveal a house ablaze in the background. “Behind it,” Zack affirms, typing intently on his phone. Later, still in the car, Yeat asks if I want a beer. He hands me his phone with an animation of beer that drains as you tilt it. “You spilled,” he giggles.

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own Jester (background) wears hoodie and stole ANONYMOUS CLUB

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own Jester (background) wears hoodie and stole ANONYMOUS CLUB

Later that night, I arrive at the blocky, fire-engine-red, 6,300-capacity Zénith arena and find Yeat sprawled back- stage on a long couch, eyes glued to his phone, blasting Lyfestyle. The atmosphere is mellow; Field Trip team members and Zack’s family lounge around. There’s a charcuterie board and a fridge stocked with Celsius energy drinks. Yeat’s been asked to transcribe his songs because his vocals are semi-incoherent and the label needs to prepare lyrics before the album’s imminent release, so he hunches over a laptop and plugs away.

When Zack leaves to do his opening DJ set, I seize the chance to uncork my most invasive questions – such as whether he’s a one-or two-ply toilet paper guy: “Next question.” I ask Yeat about Drake, with whom he scored last year’s US number-two hit IDGAF. “He’s the homie. Just a really great guy. We made a couple really good songs. I fuck with him. He’s bro.”

I probe further, asking Yeat what he thinks about the many detractors who accuse him of forcing his enigmatic persona. “It’s not like I’m trying to be mysterious, I just do things in a certain way,” he considers, rolling over his thoughts. “Making things feel more important instead of spamming it all day, looking for attention.” He says he’s not introverted at all, but picks and chooses who he wants to reveal his intimate self to. “Show me their schematics and if they’re pretty similar to mine, there could be an alignment. If it’s way off, I’ll never talk to them again.”

Yeat wears jacket CARHARTT WIP and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own. Jester wears hoodie and trousers ANONYMOUS CLUB

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL and T‑shirt, trousers, balaclava, sunglasses and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL and T‑shirt, trousers, balaclava, sunglasses and jewellery talent’s own

Yeat wears jacket DIESEL, trousers and belt CHROME HEARTS, shoes RICK OWENS and T‑shirt, balaclava and jewellery talent’s own

The rest of the pre-show is pure goof-off, like we’re seshing at Yeat’s crib. He giddily plays me an AI-generated clip of him shooting himself in the face with a gun, spewing gory blood everywhere. Swaggering in front of the mirror like De Niro in Taxi Driver, he suits up with a skull-themed Rick Owens balaclava over his face. The Francophones in the room teach him how to say “this is a movie” in French.

Right before he’s set to walk out, he and the Field Trip crew take ritual shots of Grey Goose, making sure to lock eyes to forestall a future of lacklustre coitus. Down in the crowd, I weave through the Bape and Balenciaga for a prime viewing spot. There’s a tattooed muscle bro with a topknot who looks like a Nordic, almond milk-loving Yeat. A young woman wearing a Bladee football shirt sways excitedly next to a friend. Right in front of me, a kid who looks about six clutches his chaperone’s arm. Everyone is, bien sûr, French, so everything I overhear is incomprehensible, but the joie de vivre needs no translation.

Unexpectedly punctual, Yeat actually begins minutes before he’s slated to start. He blisters across the stage, barely visible amid the smoke and atop a gargantuan platform that’s like the Great Wall of Yeat. His show goes full Twizzy Swift and takes us through his eras, from the bouncy swag of 2021 mixtape 4L through the baleful drift of AftërLyfe, the hypnosis-inducing soundtracks of 2093 and the shrieking delirium of Lyfestyle. The set has the gaudy thrill of a Six Flags roller coaster ride, with a cartoon narrator and animations that show years whizzing from 2024 to 2093. After Yeat plays the wiggly Monëy so big for a second time, with an electric guitar edit, he dissolves into the smoke like a spectre.

Have we reached peak Yeatmania? To date, he’s dropped four mixtapes, six EPs and five studio albums, most of which are more than 20 tracks long. It’s hard to imagine what more he could do without the bombastic hyper-rap sound wearing thin. On Lyfestyle, he hasn’t radically altered his mutant rage mayhem with newly freaky inflections or deranged concepts. Instead, he’s retreated to his OG sound and dialled up the energy levels to max monster. Still, Yeat’s unwavering in his confidence.

Earlier, I’d asked him about his interest in historical events, which he explained as history being the only time period between the past, present and future that he can’t impact in some way. The past feels more “powerful” to him because it’s already set in stone; no matter how high he soars, no Victorian child will ever know Yeat. But maybe every Gen Alpha kid will.

“The past is something I can only learn about,” Yeat muses. “The future I’ve already taken control of.” As I’m driven from the venue in one of two Benz vans, a throng of teens chase us up the exit, pulling out their phones and screaming “Yeat! Yeat!” into the window. Realising Yeat’s not in the vehicle, they sprint after the other car, but their chance of a close encounter with this otherworldly rap star slips away. With the supermoon gleaming overhead, his Benz speeds off into the night.

CREDITS

PRODUCTION Connect The Dots EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Wes Olson PRODUCER Zack Higginbottom PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANTJess Propper STYLIST’S ASSISTANTS Hollie Williamson, Jester Bulnes and Jesus Gallegos Yela PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR Nicole Morra PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Khari Cousins and Mark Cheche