The Black Art Matters protesters calling for change

Saadiyah Islam, Karin lelengboto, Poppy Aiken

We hear from the people on the ground standing against the severe under-representation of Black/POC artists and faces in the UK’s long standing art institutions.

Society

Words: Neve McLean

Photography: Florence Omotoyo

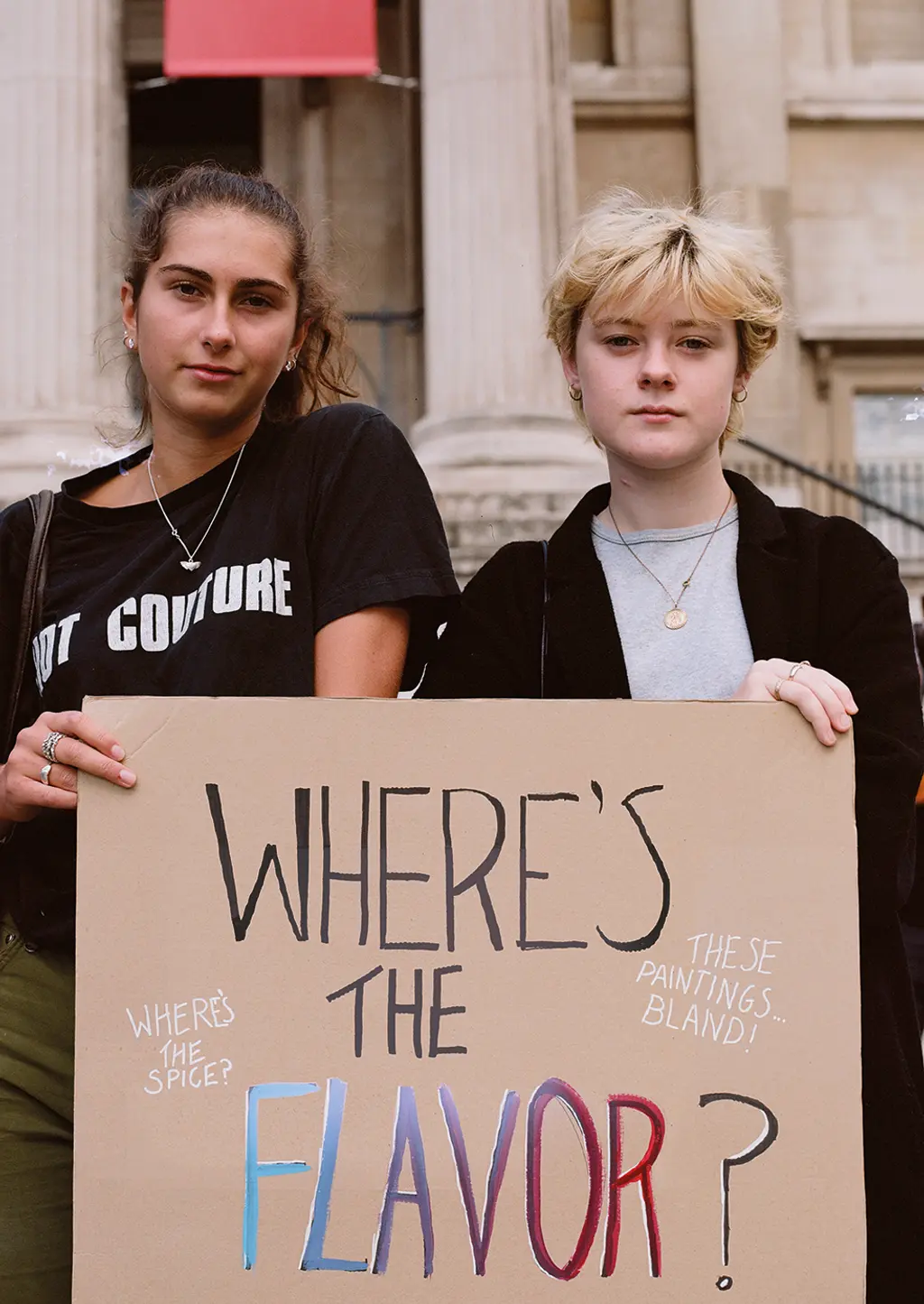

It’s Saturday 5th September and, outside the National Portrait Gallery on Trafalgar Square, a group of protestors are chanting: “Where is the spice?”

They’ve gathered here in central London to highlight the severe under-representation of Black/POC faces and artists in the UK’s long standing art institutions. This is Black Art Matters, led today by Annis Harrison, a London-based educator and artist. Auditing the galleries, she counted only five works by Black/POC artists in the 124-year-old institution. In fact, a recent survey of the country’s public art spaces revealed that, of approximately 2000 pieces of Black art, many of them are sitting in storage.

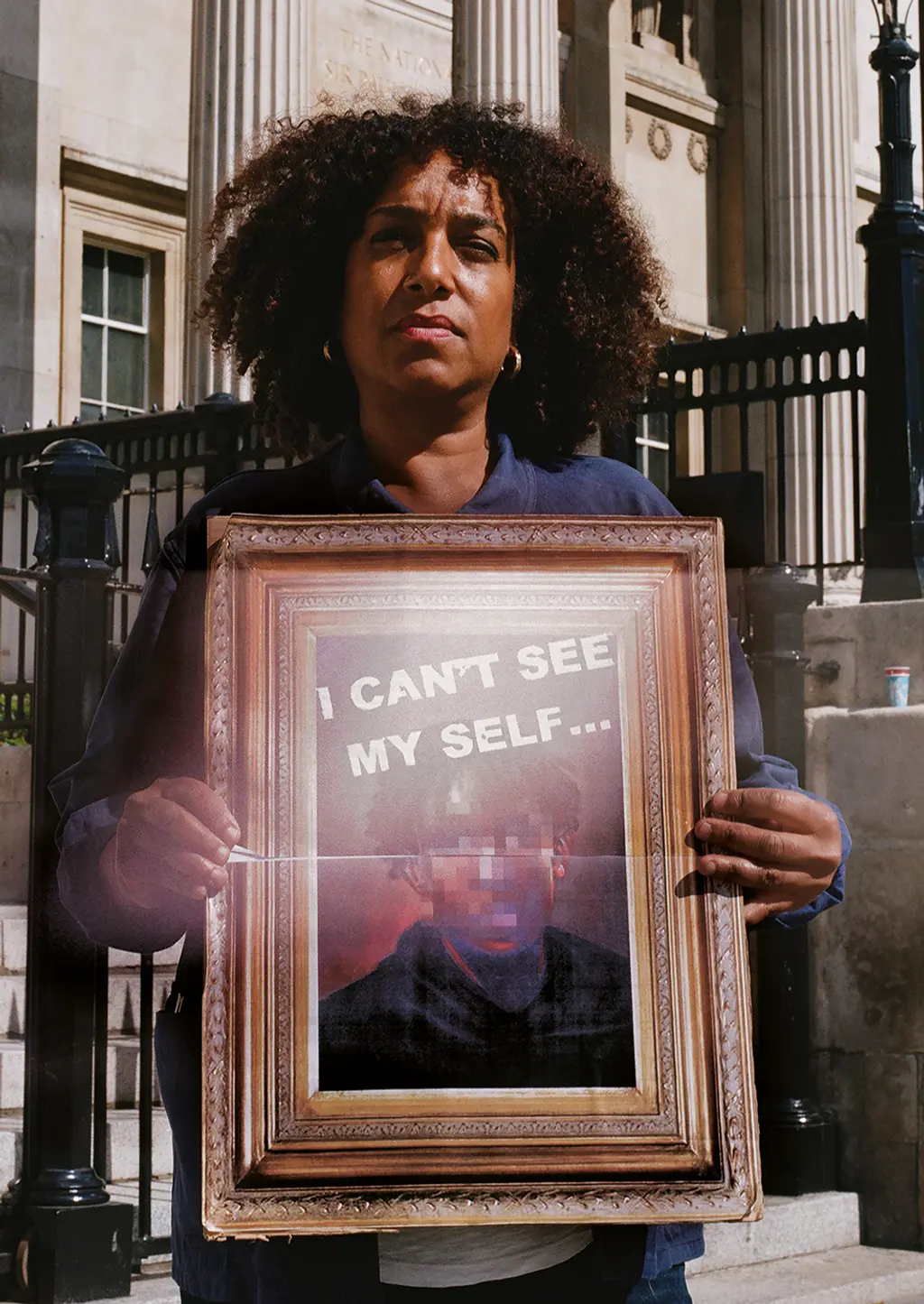

Harrison’s protest echoes the pioneering Black art movement of the ’80s – she refers to a 1989 exhibition, The Other Story, at London’s Hayward Gallery, which celebrated the contribution of artists from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean to art in post-war Britain. She and her peers remember thinking this would be a turning point. Yet today’s placards asking “Where are the colours?”, “Where am I?” and demanding that national establishments “Decolonise your galleries” demonstrate that there’s still a lot of work to be done.

Adding their voices to the Black Art Matters rally are Patrick Vernon OBE, founder of the 100 Great Black Britons campaign, Bolanle Tajudeen, founder of Black Blossoms School of Art, and poet Rakaya Fetuga. As Vernon asks of the noisily positive crowd gathered in early autumn sunshine: “Why are we always portrayed as victims or perpetrators, not writers or champions?” And, as Tajudeen sarcastically ponders, raising the ongoing controversy of art looted by Britain in the days of Empire: “Maybe if they could steal it, it would be on the walls.”

Mila Harrison

Mimi Emrys and Katie Dermody Palmer

Annis Harrison

Annis Harrison, 53, artist and educator

Why are you here today?

As an educator I take art students to the National Gallery and we look at identity. London schools are full of diversity, so I try to make my lessons connect with the students. But I became acutely aware of the lack of diversity, the lack of the image of Black people, or any Black artists within the National Gallery. There’s a history of Black artists in this country that are not being seen.

Our national institutions must take responsibility and show Britain’s true art history – because if you are walking into galleries, national institutions and you can’t see yourself, why would you carry on with this? Why would you think that anyone is ever going to pay you any attention? So it’s really important to inspire, not just Black people or POC but white people to know the true history of the arts in this country.

So how do you think that change needs to be implemented?

We need to look at the boards within our institutions and make sure those boards are not white male-dominated. At the moment George the Poet is part of the Arts Council board – it’s about having more board members that recognise the art’s importance. Also, teachers, educators and universities need to look at Black history and include that in their learning. It needs to come from multiple places.

Tell us about your project that’s tackling this issue

Traditionally, when the Black image is painted in this country, the Black person isn’t allowed to look at the viewer, or they’re placed below the white person in the picture so they either have to look sideways or look up towards the Lord. So I created a series of portraits, of young people, between the ages of 11 and 19, of mixed heritage, in which they all look at you. It’s all about the next generation coming through and claiming their space, [and] actually being recognised. They will be presented with gilded frames in a show at VO Curations [in central London] from the 6th to 10th October during Black History Month.

Abondance Matanda, 21, writer

Why are you here today?

First and foremost because I believe that Black Art Matters, and the main incentive was Bolanle Tajudeen doing a speech. I rate her so much, and I like her journey and observing what she does. I wanted to hear the poetry, too, because I write poetry, so I’m always interested in seeing how and where poetry is used and can be used on an activism level.

How do you feel about under-representation in our national art institutions?

Quite underwhelmed by it – it’s just disappointing. It just feels like there’s no care. Museums and galleries are meant to care for the objects and art pieces. And they’re meant to care for the audiences that are taking this in. So they’re just neglecting one of their main functions. But it’s a source of motivation for actually being meaningful with the cultural work that I produce. It’s just a thing of finding a silver lining.

What do you think needs to change?

One of the key things is the workforce. The professional culture within these institutions needs to be more welcoming for the people who actually have lived the experience of the subject of Black life. Even before [you get to thinking about] the art history and all the educational jazz, nobody gives a toss about that. It’s more the people that are in charge of putting these shows on and getting objects into the collections – do they actually understand the real-life impact and importance it has beyond reading about it?

Bolanle Tajudeen, 31, founding artistic director @blackblossoms.online

What is Black Blossoms?

We highlight Black women and non-binary people of colour in the arts. Recently we launched Black Blossoms School of Art and Culture, which aims to decolonise art histories.

Why are you here today?

There is a problem with the amount of work that is acquired by national institutions from Black and POC artists. I don’t think it’s reflective of the art world and there needs to be more Black and POC representation at decision-making levels, that sit on acquisition teams. It’s all good and well having Black staff that don’t have much power within the gallery. But we need staff to say yes and no, and really push for strategic direction that is more inclusive than what we have now.

What do you think needs to change?

POC staff need to feel empowered to make the changes. Boards should change so we don’t have certain people being like: “Oh my gosh! We need to retain this heritage and legacy of white supremacy within our collections.” We just need an overhaul. And people shouldn’t be scared.

What’s really interesting is Steve McQueen’s Year 3 project [currently on show in Tate Britain] – he took pictures of every Year 3 class in London to show the diversity of London. That is the future. If museums don’t catch up, museums will become obsolete. People will [ask]: what’s the point of funding these institutions if people are not going to them?

Diana Puntar, 53, artist

Why are you here today?

As an artist, I’m aware of how representation works. The system, like so many other institutions, has been developed with inherent white supremacy, [which is] shown in the way that artists and artworks have been chosen. [This has] resulted in the under-representation of Black artists internationally. People come to the gallery and they think that’s a fair and equal representation of what art is, and who important artists are. It’s a false history.

What do you think needs to be done?

The history needs to be corrected, permanently. It’s not something that comes up once a year for Black History Month – it’s not a trend. It needs to be corrected and talked about, and it needs to be totally transparent. When one institution does that, it has an effect on everyone that comes to the museum, [then] other museums, and it ripples out to people who might not be thinking about art and why they see what they see. It’s one of endless steps that need to be taken.

Luca Harrison and Starin Bisala

Luca Harrison, 16, student

Why are you here today?

Because I believe there needs to be more representation in not just galleries but schools and all other institutions, too.

What do you think needs to be changed?

There needs to be a huge increase in what is shown from POC artists and faces. There’s over two million Black people in the UK and [institutions] need to embrace that and understand that that’s a part of British culture – Black people have been in Liverpool since the 1700s!

Starin Bisala, 16, student

Why are you here today?

Our voice needs to be heard in every art form, fashion et cetera, and we need permanent change. I don’t do art but I feel it’s a good way to understand each other and how we express our feelings. It’s very vital for young Black kids like me to have people in big places like the National Portrait Gallery and have representation, so that when we go there we feel like we can relate.

When you go to galleries, do you notice that you don’t see anyone like you?

I saw that a lot. And when I did see dark complexions it was usually in a negative light. It’s demeaning to me and dampens our culture.

Would you say you have had to work much harder to feel as empowered as a white person would, seeing so many beautiful paintings of white people when visiting the gallery?

One hundred per cent. I feel like we have to look in really specific places. We need more representation so we can feel as empowered as every other person in London.

Are you hopeful things can change?

I think 2020 is the year of change. A lot has been happening for us, a lot of us have finally spoken up and had a voice, so I think we can definitely see an increase in representation.

Allister Augustin, 44, data analyst

Why are you here today?

It’s hard enough being an artist – it’s not like working in finance! It’s really important to have people backing you, so I thought it was worthwhile to come.

How do you feel about the lack of representation in national art institutions?

I think about when I was a kid, and every gallery I went to told a story, but it wasn’t necessarily my story, or anybody that I knew. It seems like a directed thing not to have Black artists, as it doesn’t fit their narrative. These institutions have a narrative: “When we were in this world in the 1800s, we were the greatest” – and I didn’t feel like I had any affiliation to that.

Did it make you feel undervalued and demeaned, not seeing someone that looked like you?

Definitely. My story wasn’t important, I’m not important. The people that are important are white, middle class people – the people that are rich who keep the country moving. When I was growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, I found that even simple things like being a labourer were difficult enough because you would get stick on the building site. My generation faced a lot more racist TV programmes, more racist comedians. You put yourself in a little shell and kept your head down.

This isn’t the first Black art movement and it won’t be the last. But are you still grateful that this is happening today?

Yes, it’s overdue. I think it will take a long while for actual change to come, but I’m just glad people are still willing to do something like this. It takes someone to start the conversation, to push it rather than keep it for a summer and it disappears.

How hopeful are you that real change will come about?

I think in the early stages it won’t affect the National Portrait Gallery – maybe the smaller places. But it will take a lot longer for these guys to change their perspective. It’s all about money, right?