Faster, furious and more dangerous: how the gambling industry went hyperspeed

As modern gambling moves away from traditional bookies, towards online casinos, fantasy sports and even gaming, children as young as 11 are ending up in debt. Is it finally time for a crackdown?

Society

Words: Will Coldwell

This July the government introduced one of the most significant anti-gambling measures in years, after a hard fought battle to clamp down on the electronic slot machines known as fixed odds betting terminals (FOBTs).

With their cartoon graphics, flashing lights and Super Mario-esque sound design (imagine the electronic clink of gold coins and you get the idea), reports on the highly addictive machines – often described as the “crack cocaine of gambling” – have shone a spotlight on the industry, provoking renewed debate over how it should be regulated.

Restricting the maximum bet from £100 per spin to £2, the legislation could lead to a quarter of the UK’s 8,000 plus betting shops to close. It’s a testament to how lucrative these machines are to bookies (they pull in £1.7bn each year), as well as how far our gambling habits have drifted from the traditional flutter on a horse race or a football match.

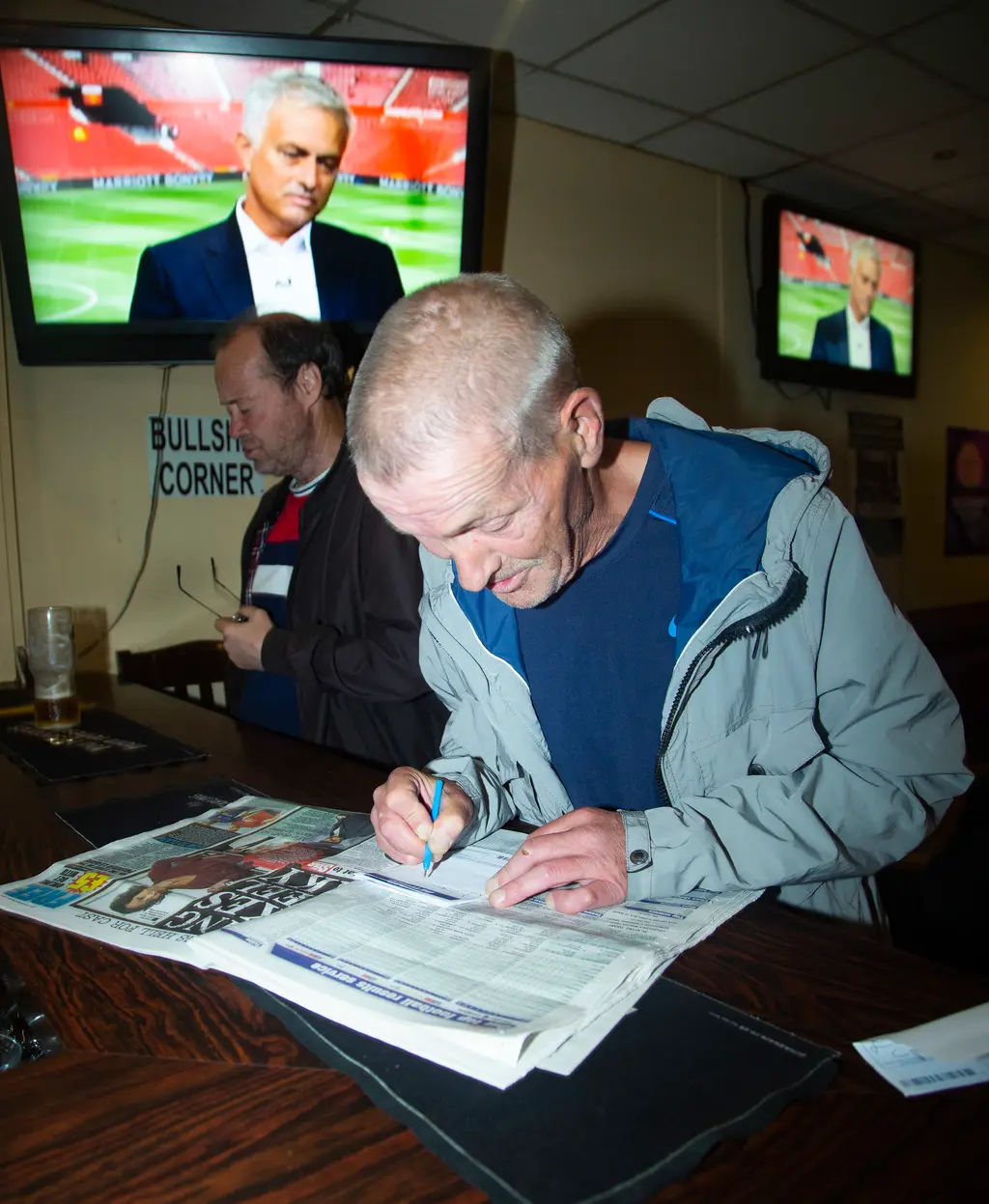

The final days of the Great British betting shop: a photo series

A quarter of British betting shops are at risk of closing. Here photographer Danyelle Rolla delves into the unique culture of the local bookie.

Photography: Danyelle Rolla

It comes as the scale of problem gambling in the UK is just being recognised: statistics from industry regulator the Gambling Commission show more than 2 million people in the UK are either problem gamblers or at risk of addiction.

With the rise of online casinos, smartphone apps, fantasy sports and a growing number of online games enticing players to chance real money on virtual “loot boxes”, technology means that young people are increasingly affected too: one in seven aged 11 – 16 bet “regularly” and the number of children classed as having a gambling problem is 55,000. In June, the NHS announced the UK’s first specialist gambling clinic for young people, part of a network of fourteen new NHS clinics to support problem gamblers across the country.

Fears of the social cost of gambling may be at a high, but the activity continues to evolve into new and unfamiliar territory for legislators. If gambling is an iceberg then FOBTs are the tip; even if they were to disappear completely, there’s still a hell of a lot of ice.

One person who’s been paying close attention to these changes is Dr Heather Wardle, a professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine currently researching youth gambling behaviour and its relationship with changing technology.

“Every time there’s any change in the infrastructure of tech and communication, the gambling industry expands and you can trace that back to the 19th century,” she says, describing how the introduction of the telegram in the 1840s swiftly led to the emergence of off-course betting, paving the way for the modern betting shop.

“If you think about what’s coming down the line with technology – if it’s anything the gambling industry can take advantage of, it will.”

For Wardle, online gambling – worth £5.6bn in the UK and another reason high street betting shops are in decline – has already transformed the experience and made it even more enticing to at-risk players.

“It’s no longer like having a bookmaker at the end of your street,” she says. “It’s like having a bookmaker standing at the end of your bed all night saying: ‘Go on, do another bet.’”

She believes it’s time that gambling was recognised as a public health issue. But while the last two years have seen the conversation move in that direction, largely thanks to campaigning groups like Gambling With Lives, led by bereaved parents where gambling has contributed to the deaths of their children, the industry continues to flex its muscles.

“If you think about what’s coming down the line with technology – if it’s anything the gambling industry can take advantage of, it will.”

When it comes to marketing, the Gambling Act 2005 was the moment that the UK really opened itself up to industry. While the legislation included requirements to protect children and make gambling socially responsible, it also deregulated it, allowing casinos, bookmakers and online betting sites to advertise on TV and radio – something that had never been permitted before. It saw an end to smokey, dark, windowless betting shops and brought gambling out into the open. The legislation, which effectively treats gambling like any leisure activity, made the UK one of the most liberal gambling regimes in Europe. It’s a big reason why gambling has become so pervasive today.

One area that has seen the most visible consequences of this is football. When Wayne Rooney returns from the US to play for Derby FC in January, he’ll be sporting the number 32 on the back of his shirt. It’s a marketing stunt bankrolled by the club’s lead sponsor, bookmaker 32red. This season alone, half the Premier League football clubs are sponsored by gambling companies, with brands from around the world paying up to £10m at a time to take advantage of the UK’s liberal laws, as well as the potential reach offered by sponsoring popular teams.

But as well as going to imaginative lengths (and paying huge fees) to plaster their logo on kits, and having adverts shown throughout TV intervals during matches, sports betting companies are offering increasingly complex – and addictive – opportunities to bet on the action. Smartphone apps in particular have enabled this; revenue from mobile gaming increased from £1.2bn in 2007 to £5.5bn in 2018.

“The diversity is enormous and the type of betting has changed,” says Jim Orford, professor of psychology at Birmingham University and founder of Gambling Watch UK.

He describes how bookmakers work hard to entice players to make complex, multi-bets in a quick fire way – difficult bets to win that make the bookies a lot of money. “The inplay on live action betting means it’s not just about whether Chelsea beat Arsenal, or how many goals, it’s when the first corner appears or the chance of winning 2 – 1 in the second half with a certain scorer. The odds are on the move constantly throughout the game.”

He adds: “Things have got faster, furious, more accessible and potentially more dangerous.”

The Gambling Commission has acknowledged that public opinion is hardening. Gambling adverts will no longer be able to appear on child-friendly online games and duties on online casino style games have been increased from 15 to 21 per cent.

For Eva Karagianni-Goel, chief commercial operator at online pools betting company Colossus, the industry could be taking a much more proactive – and assertive – approach in the face of such a critical media climate. She feels that some types of gambling – such as FOBTs or online casino style games – are far more risky than others and regulation should take this into account rather than coming up with blanket policies.

“It would be a lost opportunity if we don’t recast gambling to be the potentially positive entertainment option it should be in society,” she says. “I’m hoping that the future of gambling looks like low impact entertainment people can opt for, as opposed to high impact problematic gambling.”

Beyond the familiar formats and platforms, a new home for gambling – particularly among young people – has emerged within the expansive new digital realm: gaming.

One feature of this is the rise of loot boxes and skins gambling. Loot boxes, found in games like Starwars Battlefront, Overwatch and FIFA, are in-game purchases where a player pays real or in-game currency for the chance to win a virtual item that could benefit them within the game. These include “skins”, graphic files which can change the cosmetic appearance of a player, or other virtual goods.

A bit like scratchcards, you could spend a couple of pounds on a loot box and get a new item, or spend hundreds and gain nothing of any worth (though you always get something you can use in the game).

Since it’s not possible to cash out your winnings, loot boxes are not covered by existing gambling legislation. However, you can profit from loot boxes thanks to a lucrative online market where players sell on items they’ve won and with an estimated 6bn items listed at once, the potential for financial reward is very real. Researchers have found a link with loot boxes and problem gambling and have called for it to have age restrictions in line with gambling law.

For Archie Cochrane, who has investigated this area for venture capital firm Anthemis, where he is an associate, it represents a collision of two industries that foster very different perceptions from the public. While gambling, particularly sports betting, is increasingly seen as problematic, gaming is not traditionally viewed as a predatory product. Instead, it’s considered good clean fun, “something that children do”. As the gaming industry seeks to monetise its products, the line between the two has become increasingly fuzzy.

“For a long time the gaming industry wasn’t making any money – it was just selling games consoles, or games,” says Cochrane. “But there’s been a massive shift in the business model. Everything’s online, on the cloud, you can leverage networks and communities online and you don’t need to sell hardware. A lot of the cost has gone and a whole bunch of potential revenue streams have shown up.”

He adds: “People in the gaming industry have looked to leverage the learnings and techniques that exist in the gambling industry and embed them in their own products. Suddenly it looks a lot like the online gambling model.”

Last year Juniper Research released a report predicting loot boxes and skins gambling will generate $50bn in worldwide consumer spending by 2022, up from around $30bn in 2018. Citing a report from the Gambling Commission that found 11 per cent of 11 – 16-year-olds in the UK (about 500,000 children) had engaged in skins betting, it “strongly recommended” regulation of this activity.

This is a concern that Cochrane flags up, “Things that were previously a gambling issue are now a gaming issue and gaming is completely unregulated,” he says. “You have young people learning how to game and being exposed to gambling techniques. Then they grow up and have the potential to get involved with mainstream gambling. It’s a gateway drug – it’s teaching people what’s possible.”

He adds: “The gaming companies can take two paths; the first is they make a ton of money now and then get clamped down on. The other is they reign themselves in and develop their own safeguards and controls, which is more sustainable long term. Then it could essentially become the future of gambling, where people gamble through these gaming environments.”

“You have young people learning how to game and being exposed to gambling techniques. Then they grow up and have the potential to get involved with mainstream gambling. It’s a gateway drug – it’s teaching people what’s possible.”

So, gaming is turning into gambling and traditional gambling has gone hyperspeed. As the harms begin to be recognised – particularly for young people – is this the moment we see a crackdown akin to the public health campaigns on smoking?

Ultimately it all depends on the politics. Experts like Wardle and Orford believe the only way significant change will come about is if we see comprehensive reform on a government level. We’ve seen the consequences of the liberalisation of gambling and now it’s time for the Gambling Act to be rewritten to better reflect the digital landscape.

The Labour party – in particular Tom Watson – have shown support for this, as well as creating a public health based approach to gambling policy, but right now, it’s not in power. And since Boris Johnson became PM the chance of stronger regulation is low – he’s already said he plans to scale back on financial taxes, so the chance of a levy is unlikely. As it has done so far, public opinion will continue to be a powerful player in the debate.

Still, the gambling industry remains under pressure. “I don’t think they could believe their luck with the 2005 Gambling Act,” says Orford. “They know they’ve been on borrowed time ever since.”

But when you consider the pace of modern gambling, even borrowed time means billions gained – and billions lost.