Inside Advocacy Academy: the radical programme turning angry young people into activists

“I have really high hopes. We are always taught to aim high, so fuck it I’m aiming high. I want to be president of Interpol or the UN. Just fuck it.”

Society

Words: Marie-Claire Chappet

Photography: Madison Beach

It looks like a hipster coffee shop from the front. Vintage painted fonts on the window, bunting. Just another shop space in Brixton serving overpriced flat whites and vegan brownies.

Except it’s not.

It is the Advocacy Academy: a social justice fellowship for young people that’s turning teens and 20-somethings into activists. Can you teach activism? Apparently so. Based on the freedom school model of the State’s 1960s civil rights movement, the academy helps the hackneyed “angry” youth become verbose social justice warriors, running headline-grabbing campaigns.

The proof is in the pudding. The Academy spawned 2018’s Legally Black campaign which “ad-hacked” iconic film posters and replaced all the lead characters with black actors, putting them up all around London. The tagline of each read: “If you’re surprised, it means you don’t see enough black people in major roles.” You probably came across one, or caught it in the national news.

I meet one of its founders, Liv, 20, at the academy. She’s fiercely articulate, relaxed and warm; chatting quickly but thoughtfully. She describes the reality of running a viral campaign.

“We would meet once a week or once every two weeks, we had our own WhatsApp group. It was a lot of admin and boring stuff;” she explains, “Brainstorming, shoots, logistics – going to parliament for long meetings. There was a lot of meeting up every day – unfortunately during exam period, just to get it done.”

It’s a far cry from what you might expect – angry, placard wielding marches or even smug Instagram tactics. Turns out activism is much like any other job – long hours, hard work – and yes, tedium. Ploughing through all of that requires grit. Liv, who grew up locally in South London; reading and studying voraciously on civil rights and activism, has it in spades.

Now an English student at Warwick, she is president of their anti-racism society, on the youth board of The Change Foundation [a charity that uses sport and dance to create change in young people] and is working on the rights for a TV pilot borne out of advocacy ideas. She has a focused mind (already grilling me on journalism) another vehicle she may use for her activism.

“Do you ever just chill?” I ask.

“Sometimes I have fun,” she laughs.

I’m not sure I believe her.

I arrive at the academy on a hot day in July, where alumni from its recent graduating class are gathered to train as “changemakers” – mentors for the academy’s next intake. The space feels like a nursery for political disruptors. There are cubby holes for shoes, pegged-up Polaroids of its young activists strung along the walls, bookshelves with Civil Rights tomes and Zadie Smith novels, brightly coloured notice boards plastered with activist slogans, and a houseplant called Greta.

Sitting on the floor in a circle, are roughly twenty young people, aged between 17 and 22, shoes off, sharing stories about boundaries and free speech.

“You all have something to say,” chief advocate and academy founder Amelia Viney, tells them. She is a blunt, fast-speaker with a no-nonsense approach and a nose ring. “I need to hear your voices.”

Amelia’s voice dominates – whether she wants it to or not. Despite her calls for others to drown her out, you cannot help but hang on her every word. It’s little wonder she was the pied piper who led so many of these students here, thanks to her impassioned speeches at various South London schools. Many of the students relay to me how she stood on tables and galvanised them with cries of: “What makes you angry? What are you going to do about it?”

She founded the academy in 2014 because she was, herself, angry. Working then as a parliamentary researcher in Westminster, with a background as a civil rights lobbyist in Washington DC, she saw a yawning gap in the UK for a real youth movement.

“What I saw working in Westminster was that working class kids would come to MPs with questions or problems and just get patronised,” she says, “Often they wouldn’t have the tools to effectively communicate their issue, but they weren’t told this – they were given a pat on the head. I used to think – these kids don’t need pity, they need power.”

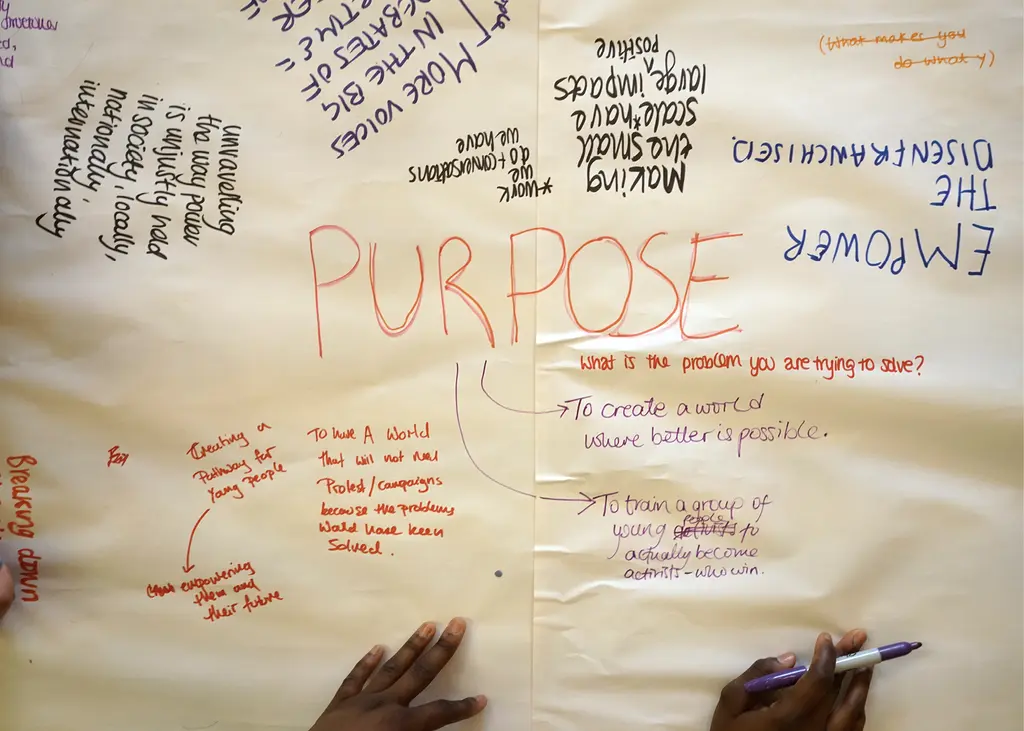

The aim of the academy is to do just that; to empower young people to channel their anger into action; to give them the tools to make a change: “I believe in order to get from where things are now to where they could be in a generation, everybody who has a toolkit – who knows how to win – has to build the infrastructure, the institutions, the structures that will allow us to transfer that knowledge and those skills to the young people that are going to lead us to a better place.”

She began recruiting the way she always has – by asking young people with no access to power what makes them angry; on basketball courts and estates over Peckham and Brixton. The geography was no coincidence. Lambeth is one of the poorest and most dangerous areas of London. Stats from House of Commons Library show that Southwark had the highest number of knife crime incidents in 2017 – 2018 with 860 offences. With over 100 knife deaths in London already this year, this is a dangerous environment for young people to grow up in. Amelia believes this is a generation of local kids “forged in fire” but not just by threats of violence – by witnessing true inequality. As one of the young activists says, of her reasons for joining; “No way I want to be just another black woman raising two kids alone on a council estate.”

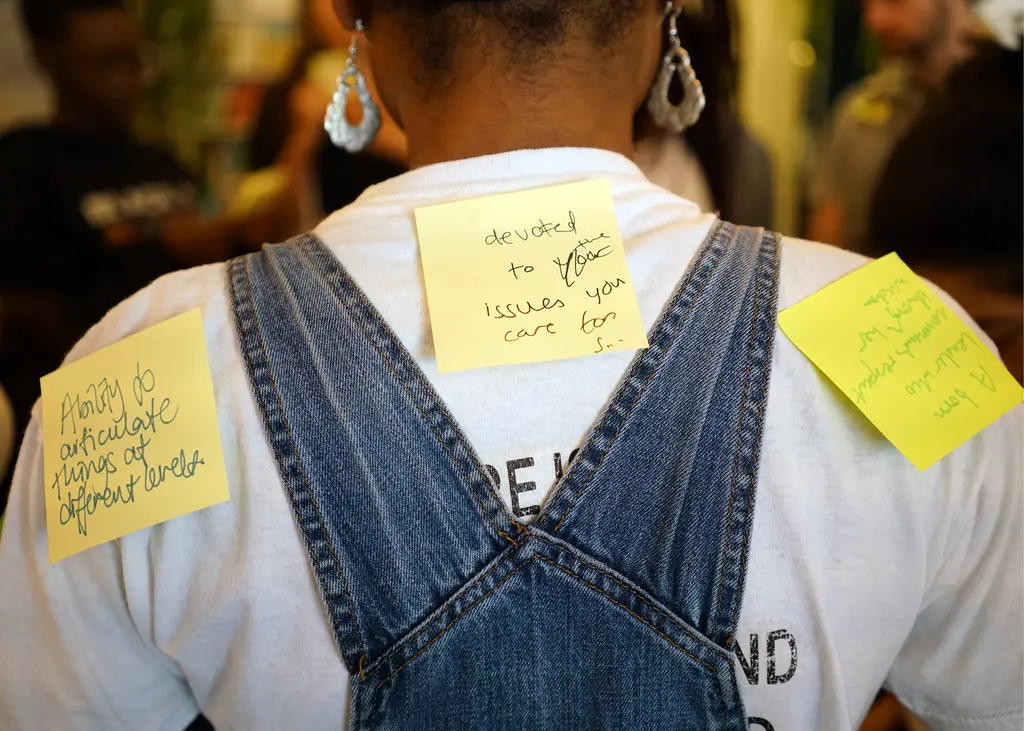

Games based on leadership characteristics

The academy was born in these environments, and is passionately local. “We started with no money and literally 12 kids in a leaky hall with homeless people sleeping in it,” Amelia says. “We are now a 350-hour, 300 volunteer youth movement.”

“I only speak when I need to – I would rather push the kids forward,” she tells me, after I witness her chairing a spirited discussion over the use of the word “gay”. Eighteen-year-old trans man Isaac has just voiced discomfort with how casually the word is used as a slur. He is part of another of the academy’s burgeoning success stories, StraightJackets: a group campaigning for LGTBQ+ sex and relationship education to be mandatory in schools. They were responsible for the widely-reported faux Ofsted banners, posted outside schools across south London and condemning them for failing to provide an LGBTQ curriculum. One of these now hangs in the loo at the academy.

“Our plan is to rewrite the system,” says Isaac. “My younger sister is only just starting primary school and I don’t want her to have the same sort of education that I did.”

Yet – in a statement that could easily belong on the Advocacy Academy’s walls – there is no judgement in the conversation I see, only learning. Offence can be taken, and noted, but it is then explored. The conversations here are open and often uncomfortable. They have an “oops” and “ouch” policy which, at first glance, seems childish and vaguely nauseating, but is surprisingly effective.

Declaring “oops” acknowledges a misspoken statement, “ouch” denotes offence. What happens next is honest and respectful discussion.

“Don’t ‘call people out’, call them in,” Amelia says. “You can’t cancel people in real life, that’s not a thing.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what I expected an activist school to look like, but it wasn’t this.

Akhera, 18, centre

Activism, the Gen Z Instagram boast of choice, has become a somewhat commodified discipline. Recently the term has been thrown around so much as to become somewhat meaningless: every second celebrity and collaboration is “empowering”, every new ad campaign makes an avaricious zeitgeist-grab by “standing for something”. A bunch of kids in South London meeting up to talk about activism could have been a circle-jerk of virtue signalling. It was not.

The fellowship involves three residential retreats and weekly evening gatherings. They work on gender, race, class, sexual orientation, through the lenses of education, housing, disability, work, finance and more. Accepted advocates are expected to create and run their own grassroots campaigns, with help from visiting activists, politicians and academics, and then deliver a speech in parliament.

It is open to anyone entering year 12 or 13, based in south west or south east London. You don’t need good grades to get in, just a good attitude. The application involves an online form, a three-minute video on “what makes you angry” and an informal interview with Amelia.

“We were stripped down to what our identity is beneath, during our interview,” says Akhera, an 18-year-old student, piercingly bright and eloquent; wearing denim dungarees and a scarf tied in her hair.

She’s part of this year’s cohort and a passionate advocate for educational reform who is currently campaigning for a more nuanced discussion of colonialism, imperialism and commonwealth histories in UK schools.

“Some children, like me, are second or third generation migrants and we never hear our stories told, or even a critical analysis of colonialism and what it was, is and has impact on,” she says, “I grew up in a radical household – my dad is a Rasta, my mum was a Rasta for a time, they both have very specific ideas that come from being second generation migrants from Jamaica. It may be a political household, where we would discuss these issues around the kitchen table, but it’s one that had no means of accessing power – we’re working class, we live on a council estate near here. We were able to discuss things, but not act on them.”

What attracted her to the Advocacy Academy, was the ability to act on these ideas, but also the fact it was selective: “Amelia came to our school, stood on the tables and said: ‘Some of you in this room will think ‘this is for me’ and some of you will not want to be involved and that is totally fine.’ That space to choose whether I really wanted to be involved, that really spoke to me.”

The Advocacy Academy, much like Amelia, does not fuck around. Indeed, when one of the young women present identifies the aim of the Academy as supporting youth issues, Amelia is direct.

“No, with all due respect, young people are just the starting point,” she says bluntly. “The net aim is justice; I expect you to go forward with that. I haven’t given you these skills so you can go off and be bankers.”

On the day I visit, the young graduates learn the practical approaches to take as a leader in any given scenario. Yet, not all those present will make the cut. The academy has high levels of support, but it also has high expectations. No one here is pandered to. It’s tough and smart, and you have to be both to keep up.

And anger is fundamental. “What makes you angry?” is, after all, the recruiting question. Everyone here is angry: from today’s youth leader Darcy and her yearning for radical education reform, to fellow leader Liz, who makes an impassioned plea for constructive dialogue with northern charm and a Ghanaian flag wrapped around her dreads. Anger is the lifeblood of the academy.

“I had so much anger before I came here. I would just snap at anyone who said anything to me that was even remotely offensive,”says Mel, a 19-year-old Latin American university student, who campaigns for mental health support in schools. She grew up near Brixton in an immigrant family and says she felt the taboo around mental health in her community sharply.

“There’s too much stigma there still,” she says, alluding to her own struggles, and referencing the fact her local school had one counsellor who left and was not replaced, “I don’t think anyone should grow up feeling there is something wrong with them.”

Her experience with the academy – which she joined after Amelia visited her school – has helped her channel her anger.

“We were just a bunch of angry kids who blamed ‘the government’ or ‘our teachers’ for everything,” Now we know what systems are in place and that it’s not just ‘the government’. We know where to pinpoint, we know strategies and tactics and we know how to build up our power. The academy helps you narrow your focus and figure out what the problem is and not just see it as this huge umbrella. It has given us a language.”

She seems remarkably calm for someone who is angry – though it may be the fact she has a stonking cold and is hugging her knees in her oversized Greenwich Uni hoodie. It may be the fact she has replaced her misdirected anger with an impressive sense of steely ambition.

“I have really high hopes. We are always taught to aim high, so fuck it I’m aiming high. I want to be president of Interpol or the UN. Just fuck it.”

The transformation of these kids into hyper-articulate activists is a consistent theme in my conversations with the young wannabee changemakers.

“I was put into a box and I could barely open my mouth. If you had met me back then, before the academy, I would have just whispered my name,” says Jemmar, a 22-year-old-BAFTA-winning documentary filmmaker and academy graduate, whose fast-talking passion seems bafflingly inconsistent with this earlier description.

She tells me about her teenage years spent in Jamaica with her family, and how she struggled with the colourism the rife homophobia. “I was bullied for the colour of my skin and the way I looked. I was so low – I tried to ‘fix’ the ‘problem’ and bleach my skin and chemically straighten my hair. I wanted lip reduction surgery and a nose job. I would put a peg on my nose for hours every day.”

The family returned to the UK when she was 16 after her grandfather had a stroke. “I became almost a full time carer for my siblings here in Brixton, while my mum looked after her dad in Harlesden. Around that time, bleaching my skin and doing my hair stopped being a priority but I still was so angry about being made to feel I wasn’t beautiful.”

I ask what inspired her to apply to the academy, when she first heard about it through friends. “Kylie Jenner’s lip challenge” she replies, to my surprise, “The craze that happened to make everyone’s lips look like mine, when I was trying to get rid of mine – I was angry about that.”

Her film, What Do You Mean I can’t Change the World?, which won the 2019 British Academy Children’s award for Best Content for Change and came about through a connection made at the academy, centres on her relationship to beauty as a young black woman. She is movingly verbose – both in person and in the film – about existing in a world that taught her the definition of beauty was the opposite of what she is.

Since she found her voice at the academy, Jemmar is now fiercely political. “At the last general election I was so excited to vote I ran to the polling station so fast I actually left my family behind!” she laughs, “I love politics and policy and I’m on the British Youth Council now, doing policy work with young people internationally.”

The academy may be political, but it is not partisan. The academy has visitors and speakers from all political parties and encourages advocate participation in Westminster. This stems directly from Amelia’s own politics.

“We accept people from all political parties and none,” she explains, “and we promote voting. It is very rarely sufficient but I think it is always necessary, even if that’s a spoilt ballot. We would work with people from almost every administration because I believe pragmatism has as much of a place in justice as principle does.”

“She told me I would be in a space where a lot of people would be sharing stories about racism and she wanted to know how I would navigate that space as a white man. She asked what I was going to bring to the space… My answer was: I’m just going to listen.”

Bel, a softly-mannered 19-year-old engineering student, is currently struggling with that pragmatism to principle ratio. An engineering student at Edinburgh, he is one of the only students who lives in an arguably more affluent area of South London, yet he has an uncomfortable relationship with money. He is hoping to become an advocate for “de-growth” which he describes as “resilience building in communities and not necessarily just growing the economy.”

Though he sees money as inherently somewhat evil, he sees the necessity of having at least some of it, to get shit done.

“I am just angry about everything though,“ he tells me, “Prison, school, housing. I’m angry about how all of these perpetuate each other. There’s no way to change any of it without destroying it, without radically deconstructing all of it.” There’s a vein of hope within his hopelessness, yet he appears crushed by the weight of the world.

“I always wanted to do good, not only for myself, but for other people,” he says of his reasons for first applying to the Academy. During his initial interview Amelia challenged him on race – another issue he feels passionate about.

“It was uncomfortable. She told me I would be in a space where a lot of people would be sharing stories about racism and she wanted to know how I would navigate that space as a white man. She asked what I was going to bring to the space.”

“And what did you say?” I ask.

“My answer was: I’m just going to listen.”

I ask Amelia, as a white Jewish woman, how she does the same.

“That is a huge part of how I navigate my role,” she explains, adding that the point of privilege is to use it responsibly. “A lot of people, out of fear of taking up space that isn’t theirs, take the skills their privilege has given them and leave, but that is not the answer for justice. I use my privilege to ensure that I deliver a new generation of change-makers.”

She does this by ensuring that the movement is largely run by alumni but also by promoting solidarity. “We don’t operate singularly for people of colour, or people who are queer or disabled, we operate in a truly intersectional and movement building way, and that is because we believe that famous: ‘Ain’t nobody free till everybody’s free.’”

The academy’s pulsating energy – which is palpable when you visit – is due to the fact it acts on its beliefs. These young people are not just theorising about activism. In fact, the grassroots campaigns started by these young activists are thriving.

But how successful have they been? StraightJackets has only just begun, and is in the midst of responding to the government’s – somewhat diluted attempts – to pass LGBTQ Sex Education legislation. Their headline-grabbing posters are just the beginning, they are now meeting with education ministers about making real change to the curriculum.

“It should be compulsory and written in the curriculum: this is what you teach, this is how you do it well. You shouldn’t have a choice, because it is not a choice. You need to open up these discussions, especially in the formative time of secondary school,” says Isaac, who speaks from personal experience.

Isaac, 18

Though he comes from a supportive, and what he describes as “very liberal and radical” family (“In my house, discussions were not just ‘life isn’t fair’ it went further than that. It was what can you do about that?”) he felt “limited” at his school. He describes a lesson on trans issues that was particuarly scarring.

“That lesson was the worst and most defining experience of my secondary school life,” he says, “My best friend said that Bruce Jenner was a fake woman. I knew at that moment I would not be able to come out to these people.”

He eventually did – but he was met to much bullying and struggle, which only served to solidify his activism. So much so that he even tried to apply to the academy before he was old enough to. He now has hopes to become a psychologist, focused towards researching a more nuanced understanding of trans people.

Legally Black – the most prolific of the academy’s campaigns, has plans to push forward with its agenda, but Liv is aware that its success does not have a definable metric.

“We went into parliament with it and everyone was like ‘what’s your ask’ who are you targeting? But our campaign wasn’t really like that, it was like, ‘how do we change opinions?’” she says, “The thing I am coming to terms with now is that, once you’ve raised awareness, what do you do with that? How do you implement that structural change?”

But the tide is noticeably turning. This is a generation defined by its ability to care deeply about everything from climate change to racism. They embody one of the Advocacy Academy’s charter statements: “There is nothing inevitable about injustice or inequality.”

Darcy believes that the education provided by the academy should be the norm for all schools and, after witnessing the energy and intellect among these young people, it is hard to disagree. If the youth – particularly those from marginalised communities, where the academy most encourages participation – are “disaffected”, the academy’s form of education makes them an affective force for change.

They may have entered with anger, but they are running on hope. “I think it is going to get better,” says Isaac, “We are seeing so much youth activism now and the rise of social media has made it easier for us to see what’s going on and gain traction from the right communities. This stuff isn’t getting filtered through anyone else now – we are acting directly. I have a lot of hope that the world will become a better place.”

After all, as the academy grows, so does its ecosystem of activists; and its potential: “I think we have 50 + alumni now,” says Mel, “You have 50 people you can call and be like ‘stand with me’ which is already just such a huge starting point.”

None of the young activists who display hope appear naïve to me. The academy has not taught them that a better future is inherent, but that they are – with the tools given to them by the academy – capable of forging one.

“I can’t wait for the day when I get to show up for these young people,” agrees Amelia, “When they are running the movement.”