On the frontline of Luigi Mangione’s first federal hearing

In Wall Street’s shadow, fury, fandom and spectacle collide. THE FACE reports from the trial that has become a symbol for America’s rage and ruin.

Society

Words: Sahir Ahmed

Photography: Trevor Wisecup

I miss my 8am flight to New York from Chicago. I barely make it onto the next one out, paying through my nose for the seat. At 30,000 feet, I can only think about one thing: Luigi Mangione.

The plane lands at 1pm, just as Mangione – the man accused of murdering healthcare CEO Brian Thompson on the streets of NYC in broad daylight last year – is expected at Thurgood Marshall Courthouse in downtown Manhattan for his first federal hearing. By the time I arrive half an hour later, he’s already been stealthily transferred inside by armoured vehicle, avoiding the cameras. Over the last five months, Mangione has become a symbol for something much larger, exposing the cracks in a healthcare system that millions of Americans feel personally screwed by.

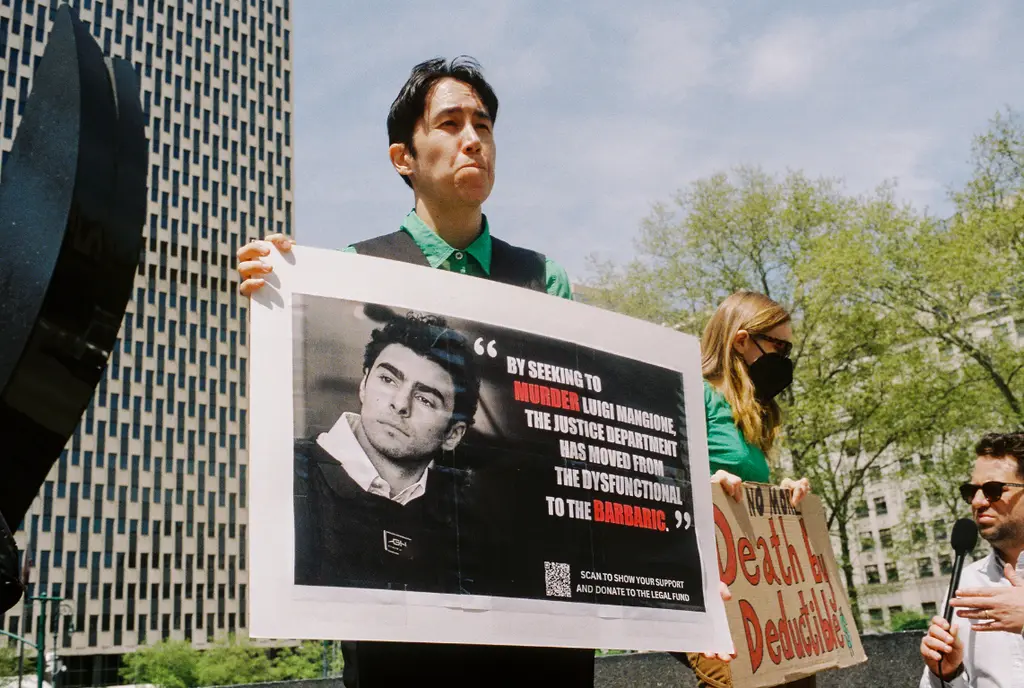

On the courthouse steps, protestors and bystanders crowd the metal barricades. A few courthouse officers loiter by the entrance, arms crossed, eyeing the crowd but staying back. Some faces are half-hidden behind keffiyehs, N95 masks and sunglasses, voices rising – chanting “FREE LUIGI” and holding signs that mirror their calls – in a chorus of grief, anger and defiance. In the crowd: dozens of Mangione supporters, death penalty opponents and tourists snapping selfies, oblivious to the fact they are photobombing a murder hearing.

Not everyone here is on his side, though. Staten Island-based artist Scott LoBaido (a self-described “patriot” and Trump supporter) wheels in a skeleton strapped to a mock electric chair, a green Luigi hat perched on its skull. Even the protestors give it a wide berth. I paraphrase: “Everybody’s banging on about this piece of shit, but no one’s talking about the man he killed,” he says. “Look at these people who follow him – what do they even do? Nothing. No work, no soul, no incentive. They need someone to cling to, so they cling to garbage like this. I’m praying he gets the death penalty.”

I’d expected more Mangione diehards on the scene, but judging by how many faces are covered, it’s clear people are worried about being here. In the current political climate, protesting too loudly can land you on a watchlist – or worse. Fear lingers in the air almost as thickly as the humidity. Just beyond the marble steps, in an icy courtroom stripped of cameras and reporters, prosecutors are laying out charges that could put a young man, 27 next month, on death row. A crowdfunder for his defence, incidentally, has raised nearly a million dollars.

So how did we get here? On 4th December last year, UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, a married father of two sons, was shot outside a Midtown hotel. Mangione is accused of pulling the trigger. Shootings happen all the time in New York, but when the natural order of power is disrupted, the American imagination stirs. The richer you are, the more immune to death you’re supposed to be.

A manhunt ensued. NYPD and federal agents scoured the city. News anchors speculated that Mangione had left the state, maybe even the country. On 9th December, he turned up at a McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania. In his battered duffle bag, authorities found a gun, a silencer, a forged New Jersey ID, a wad of cash, and a handwritten manifesto, in which he claimed to be acting alone.

Outside the courthouse, opinions splinter. “I don’t think killing is ever the answer,” says Sydney, 28, standing near the barricades. She’s visiting New York from Lafayette, Louisiana, scouting jobs in social policy. “But this case shows how tired people are of corporate greed in America.”

Healthcare hardship is what pushed Sydney toward public service after she discovered she had a tumour a few years ago. “I have insurance,” she says, “and I’m still paying off thousands in debt.” She works four jobs. “Minimum wage where I’m from is still $7.25 [£5.40 an hour; the UK’s adult minimum wage is £12.21 an hour]. Most people I know are making a lot less than the poorest person in New York.”

In the US, having health insurance doesn’t mean everything is paid for right away. When you rack up a medical bill – for surgery or a hospital stay, for example – you have to pay a certain amount out of pocket before your coverage even kicks in. Say you need $20,000 worth of surgery; if your deductible is $2,000, this is the amount you need to pay before you even see a dollar’s worth of insurance money.

This is the case because insurance companies are built to minimise how much they have to pay out. Shane, 35, an emergency room doctor leaning against the barricade leading up to the courthouse, puts it simply: “There are two kinds of people: those who hate their healthcare and those who haven’t had to use it yet.”

He and Morgan, 50, are here advocating for the New York Health Act, a proposed programme that would treat healthcare as a public right, not a private business. Every shift, Shane sees the wreckage firsthand. But the real tragedy, he says, is that “private insurance companies are literally built to deny care, to pocket money while patients jump through hoop after hoop”. The worst case scenario is a “catastrophic healthcare event” – a single hospital bill that eats up half of your yearly wage. One unlucky trip to A&E could leave you skint for an entire year.

“We’re at the endgame now,” Morgan adds, circulating flyers about the programme. “People are suffering needlessly, dying early, and there’s no plan in place to fix it.” Everywhere universal healthcare is established, it works. But in the US? We’re still pretending it’s impossible. “And it’s not just the right thing to do, it’s the smart thing financially,” she continues. An economic analysis showed that the bill would save New York $17 billion (£13 billion) a year; as of 30th April, UnitedHealth Group’s revenue is estimated at $409 billion.

In his early twenties, Mangione was diagnosed with spondylolisthesis, a spinal condition that left him battling chronic pain even after surgery. The rumour is that this ‘radicalised’ him, but his digital trail paints a different portrait – not of a hardened ideologue, but a young man dealing with very modern anxieties. He was interested in climate change, AI startups, Malcolm X and PayPal CEO Peter Thiel. He favourited Kurt Vonnegut quotes on X about poor Americans hating themselves, while reposting gripes about ‘wokeness’. He was highly educated, critical of both Trump and Biden, and espoused neither straightforwardly right-wing or left-wing politics. Mangione, as The Guardian put it, represents “the median American voter”.

When the news broke that Mangione had been found, the internet’s reaction was immediate. TikTok dissected his mugshots like they were stills from the year’s hottest A24 release. X both seethed and thirsted with posts too vulgar to repeat here. “They’re not wrong. He’s hot,” says Riley, 20, tugging at her black “FREE LUIGI” T‑shirt. “But that’s not the point. It’s easier to focus on how he looks than on what he says about us as a country.”

Riley’s mum’s a nurse. “She’s always telling me horror stories about how hard the deductibles hit her patients,” she says. “The dream would be to free the guy. I don’t think he deserves to be there. But with how politicised this already is, I doubt it’ll happen.” As the courthouse doors creak open, a ripple runs through the crowd: “Is it over?” “Will he come out the front?” “Is that Mangione?”

A masked 27-year-old taps me on the arm. “Can you mention I’m with @freeluiginyc?” they ask. “I’m against the death penalty. I don’t think the state, or anyone, should get to decide who lives and dies.” And the media circus? “They’re focusing on [Mangione’s] looks and background to distract from the real issue.” An Ivy League graduate and heir to a Baltimore country club family that owns half of Maryland’s golf courses, Mangione grew up surrounded by privileges he eventually came to reject. It’s a compelling narrative that has largely dumbfounded the press: this is not the type of person who murders in broad daylight.

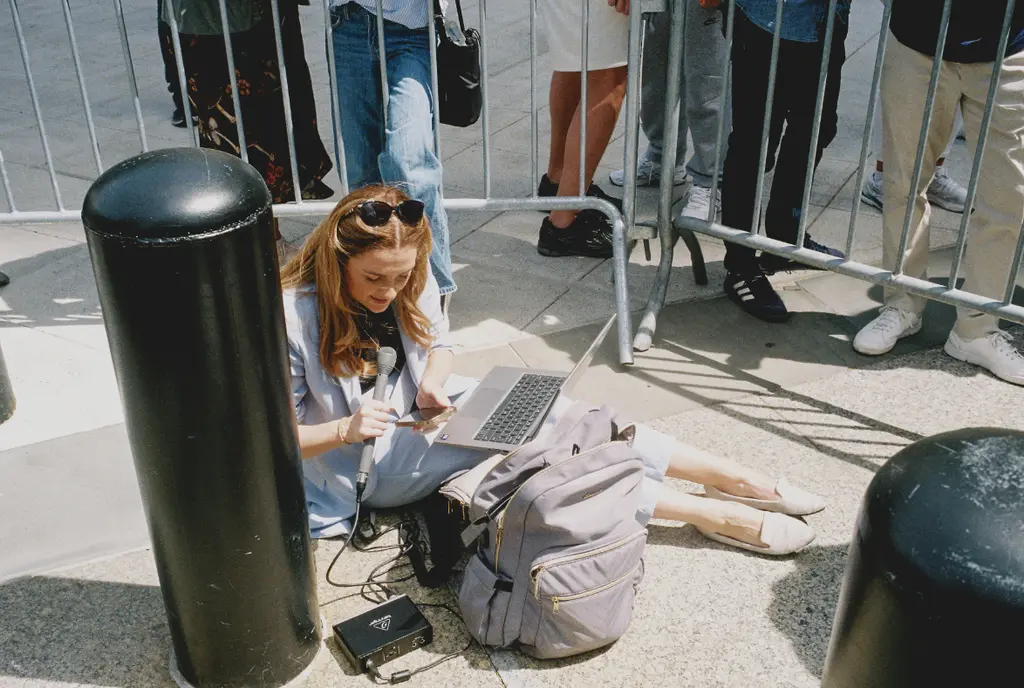

After a while, a trickle of lawyers spills out of the courthouse doors. Then comes Chelsea Manning – the former US Army analyst and whistleblower who leaked classified documents about the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. “This is a speedrun, that’s what this is,” she snaps. “You don’t do that, you don’t speedrun justice.” In other words, she thinks the case is being rushed. A reporter asks what she thinks about the death penalty. Manning doesn’t hesitate. “This is unprecedented,” she says. “Obviously, they weren’t going to do that until this case got highly politicised. I’m a supporter of the justice system being fair.”

Behind us, a black truck rolls by, broadcasting footage of Mangione in an orange jumpsuit from his arrest hearing alongside a message from the ACLU: “NOBODY SHOULD BE KILLED BY THE STATE FOR POLITICAL GAIN.” I imagine what he’s thinking in the courthouse; I wonder if he’s thinking about his birthday on 6th May, whether whoever’s around in the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn will think to cut him a cake.

The crowd stays put. I meet Dorit, 51, standing stiffly behind a sign that reads “NO DEATH FOR LUIGI MANGIONE” with the Death Penalty Action website printed at the bottom. This is her first time protesting against capital punishment. “It isn’t supposed to happen in New York,” she points out. The state scrapped the statute in 2004, but Mangione crossed state lines and healthcare is federal business (when it wants to be). That was enough for big-time prosecutors to step in and make him eligible for the death penalty. In court, Mangione enters a not guilty plea against federal charges of murder, firearms offences and stalking.

Nearby, Peter, 39, swings a sign explaining jury nullification. Originally from Moscow and now living in New Jersey, his bluntness carries a Russian-Jersey twang. “Billionaires should be terrified,” he says. “And let them be. I hope the ruling class sees just how tired we are of being fucked over.”

Nadine, 59, wearing watermelon earrings and a green Luigi hat, her sign reading “LUIGI BEFORE FASCISTS,” lingers nearby. Originally from Trinidad and Tobago, and now living in Waldorf, Maryland, she drove up especially to support Mangione. “If guilty, he should suffer the consequences,” she says. “But he shouldn’t die. It’s clear that the death penalty’s being used to set an example. Meanwhile, the same DOJ didn’t even seek it for Patrick Crusius, the El Paso shooter who killed 23 people” (the death penalty is legal in Texas).

Behind us, where Mangione’s supporters have thinned out, once more the protestors in keffiyehs, N95 masks, and sunglasses take their place. This time, their signs read: “MELT ICE,” “SHUT DOWN RIKERS” and “IMMIGRANTS ARE NEW YORK”. For all the fervour Mangione’s case has created, here in America, it’s just another day at the office, as one protest rolls into the next.

Nadine watches them too, before turning back to me. “And don’t think this is separate from Palestine,” she says. “Trump’s cronies are trying to turn Gaza into a resort and dump its people into Somalia. All of it is the same.” She wasn’t always this radical, she explains. “But I’ve learned that if I want people to be there for me, I have to be there for them.” She pauses, then her voice rises: “Until all of us are free, none of us are.”