Number 10’s race report paves a path towards more oppression in the UK

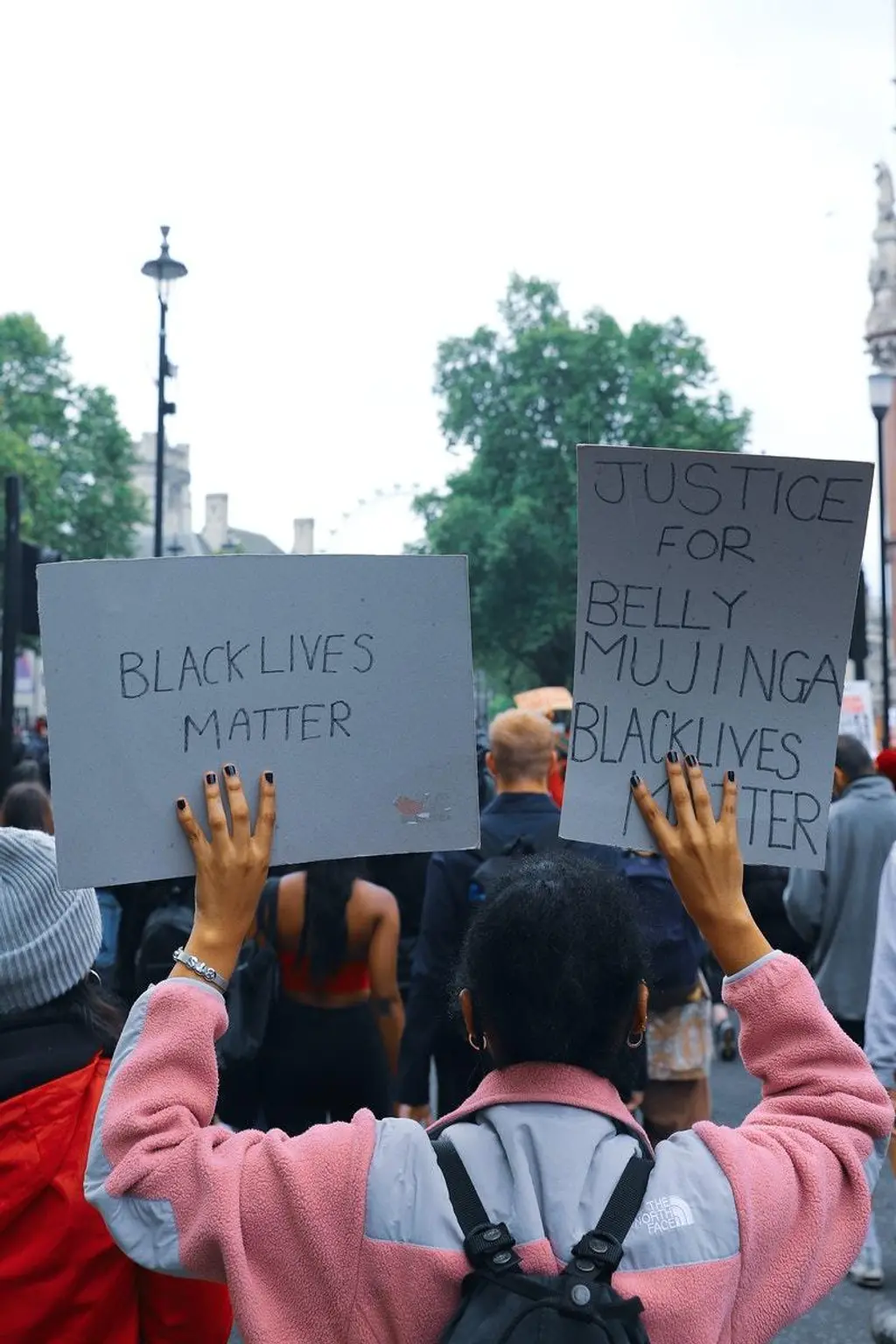

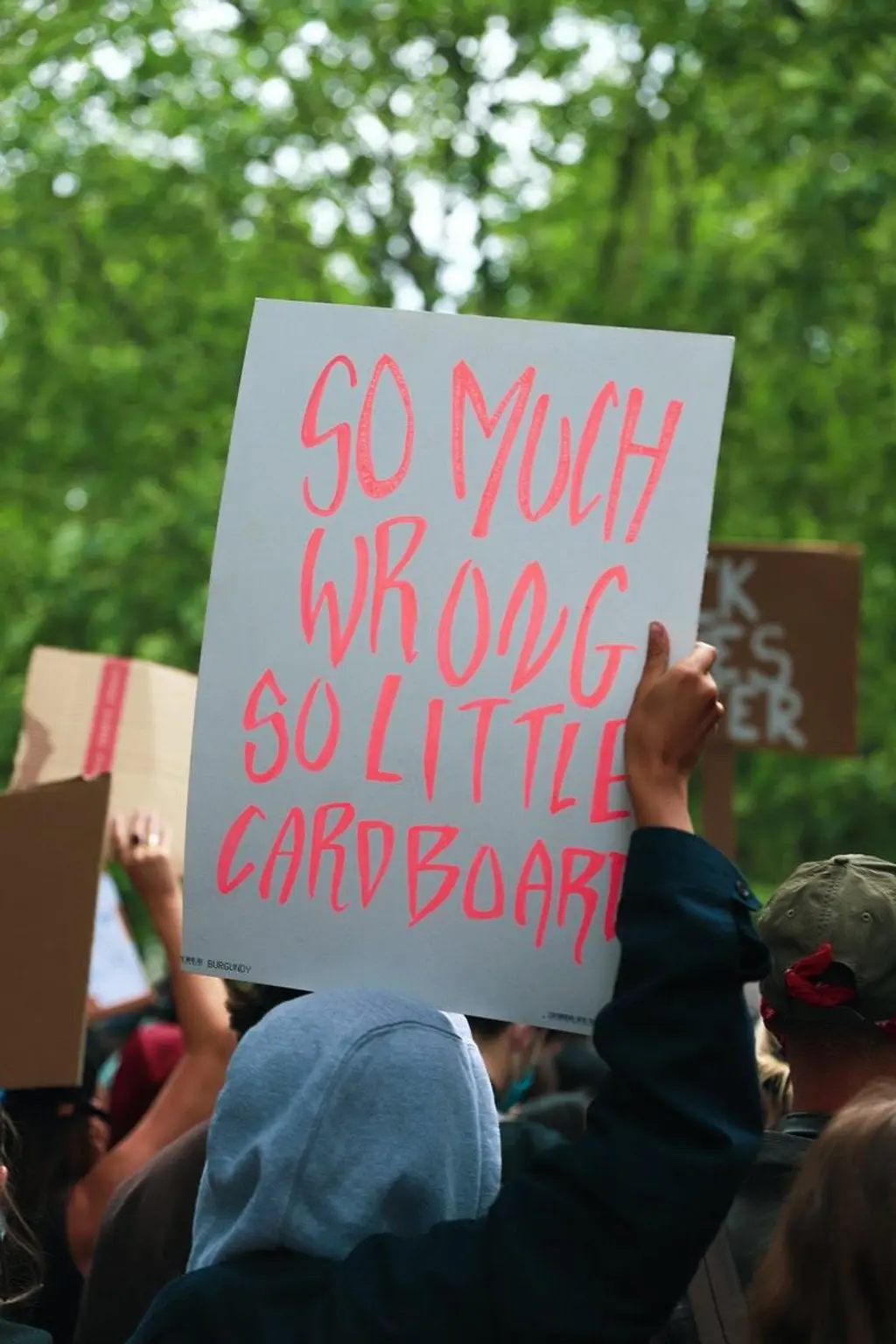

The Voice: The government’s commission on race was supposed to address the concerns of the Black Lives Matter protesters who took to the streets last summer. Instead, it appears to be an attempt to silence them, setting a dangerous precedent for the future of race relations in the UK.

Society

Words: Micha Frazer-Carroll

Photography: Serena Brown

When Number 10 chose consultant and charity CEO Tony Sewell to chair its commission on racial disparities in the wake of last summer’s seismic Black Lives Matter protests, anti-racists were not optimistic. The commission was intended to address protesters’ concerns relating to structural racism across immigration, policing, prisons, health services, housing and education, but many pointed out that Sewell had written in an article for Prospect in 2010 that he believed institutional racism might not exist. Things did not bode well.

The final report seems to reflect those beliefs. The document, which was released on Wednesday and is 264 pages long, states in its overall findings that while “outright racism” still exists in the UK, the commissioners “no longer see a Britain where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities”.

Their message to the thousands of people who participated in the protests last summer? “Too many people in the progressive and anti-racism movements seem reluctant to acknowledge their own past achievements”. In other words, organisers and campaigners have pessimistically exaggerated claims that the UK is racist and should congratulate themselves on virtually eliminating structural racism across the country.

The report weaves through issues like crime, policing, employment and community, but its key argument surrounds the finding that once socioeconomic status is “controlled for”, all ethnic groups, barring Black Caribbean children, outperform their white peers in education. But, as anti-racist organisers have pointed out, the report fails to explore other elements of racism in education: for example, disproportionality in school exclusion, eurocentrism and censorship in the curriculum, or the Black attainment gap in higher education.

Beyond education, it also seems bizarre that the commissioners could be confronted with certain statistics and conclude that racism does not exist in Britain. For instance, young Black people are nine times more likely to be imprisoned than their white peers; Black men are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched, and Black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth. Perhaps a fundamental problem is the commissioners’ interpretation of what racism is.

In her book Golden Gulag, prison scholar and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore famously defined racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.”

In essence, Gilmore’s working definition says that racism is not something that is just interpersonal, but a phenomenon that operates on a structural level, is often connected to the state, and is linked to how and when we die. Over the last year, we have seen this principle at play in the UK, where the Covid-19 pandemic has disproportionately killed people from ethnic minority backgrounds, and in particular, Black people.

But the report intentionally takes a much more blinkered stance on what racism is, focusing instead on perceived individual moral failures. Notably, it calls for more focus on “the extent individuals and their communities could help themselves through their own agency, rather than wait for invisible external forces to assemble to do the job”.

In the report’s foreword, Sewell also suggests that, since African and Caribbean children “sit in the same classrooms”, but Caribbean children fare worse in the education system, racism cannot explain the latter’s underachievement. This, of course, completely overlooks that racial disparities in education are caused by a complex variety of structural factors and are not simply the result of individual teachers discriminating against individual students.

Further demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of what racism is – by “controlling” for socioeconomic status in its analysis of educational outcomes – the commissioners attempt to separate race from class. They also suggest that poverty is a better metric than race when it comes to explaining inequalities in Britain, conveniently ignoring the fact that half of Black and minority ethnic households live in poverty in the UK. This, by the definition set out by Gilmore (which is shared by many anti-racist activists and campaigners), is certainly evidence of structural racism.

Unsurprisingly, this report, which is riddled with contradictions and distortions, has outraged most who believe themselves to be anti-racist, from centrists to radicals. Yet critics have used different words to describe what the commission’s conclusions represent. Some have called it “gaslighting”, a descriptor that moved from the interpersonal to the political realm in 2016, after Teen Vogue columnist Lauren Duca wrote that Donald Trump was “gaslighting America”. Others, with a view to applying a structural analysis over an interpersonal one, have called it “propaganda”.

The propaganda angle is an important one – after all, the report is only the most recent blow in a sustained attack on ethnic minority communities from Johnson’s government. Just last week, Home Secretary Priti Patel set out a “new plan for immigration” that would criminalise 99 per cent of the global refugee population if they were to attempt to enter Britain, a move that could contravene the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention.

Throughout 2020, as the pandemic continued to kill Black people at a higher rate than any other ethnic group, the government chartered at least 20 deportation flights, despite still not having implemented the recommendations of the Windrush Lessons Learned review.

As protesters took to the streets over the summer to show resistance against structural and institutional racism, Prime Minister Boris Johnson told us that the UK is not a racist country. Meanwhile, in education, the government recently introduced guidance stating that schools in England must not use materials from anti-capitalist groups or those who promote “victim narratives that are harmful to British society” – which was interpreted by many as a clear reference to Black Lives Matter activists, who were also targeted in this week’s report.

In the context of a government that is increasingly structurally violent towards people of colour and is pushing through a new bill that would infringe on our right to dissent, the publication of this report makes sense from a strategic perspective. It serves to bolster and legitimise the government’s continued assault on racialised people and anti-racists.

So, it is likely that the commission’s report will lead to more of the same from the government, only strengthening its ability to ramp up border violence, racist incarceration, barriers to anti-racist education, compulsory nationalism, state surveillance of people of colour, and limits on our right to protest. All of these factors come together quite symbolically in one proposal outlined in the new Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts bill, which suggests the introduction of a 10-year prison sentence for defacing a statue.

It is too soon to say exactly how these ideas will manifest in terms of policy, but it is clear that this report could easily serve as an “evidence base” to justify the government’s continuous structural violence against racialised people.

This is neither the beginning nor the end of the government’s efforts to stifle anti-racism in the UK. But in the face of a new affront to ethnic minority communities, it is our job to continue to get educated, and to get organised.