Inside the battle for Stonehenge

In November 2020, the government approved £1.7bn plans to build a dual carriageway on the grounds of Stonehenge – a site as old as Egypt's pyramids. Now a mix of residents, archaeologists and Druids have come to together to fight for its protection.

Society

Words & photography: Jak Hutchcraft

There are about 150 people around me, all walking with purpose towards the ancient stones.

“This is going to be bigger than Newbury, bigger than Fairmile,” Dan Hooper – formerly known as Swampy – explains to me as we approach the barbed wire fence. “This is just the beginning.”

It’s a dour, wet December morning and I’m with protestors at Stonehenge in Wiltshire, South West England, who are fighting against a proposed road tunnel near the site. Activists, like Hooper, are wearing high-vis jackets covered with slogans and poetry scrawled on with a black marker pen; some are wearing robes and have Druid markings on their face; others are carrying staffs and instruments. After meeting them at Woodhenge — a small Neolithic stone monument three miles from Stonehenge — we’re walking a muddy pilgrimage through fields and lanes.

In November 2020, transport secretary Grant Schapps approved a £1.7 billion project, which will include eight miles of extended dual carriageway along the A303 in Wiltshire within the grounds of Stonehenge, a World Heritage site, despite the Examining Authority strongly advising against it. Archaeologists, Druids and local residents have united to protest against it. “In recent years, [Stonehenge] has become the object of a smouldering dispute that might, without care, burst into acrimonious flames,” the late writer and campaigner Elizabeth Young (Lady Kennet) wrote in the Journal of Architectural Conservation in 2000.

Those “acrimonious flames” are burning in the bellies of the protestors I speak to at the mass trespass. “We are going through an ecological emergency,” Amelia, 22, says. “We don’t need to keep building more, we need to stop building and just be kind to the planet. Focus on our human needs and not our desires.” After a couple of hours of speeches, chanting and ceremonial dancing, the protestors leave the site untroubled by the English Heritage staff that work there. The police aren’t called and the protestors are free to continue their protest by walking the route where the road tunnel will be built.

A fortnight later, on 23rd December, the campaign group Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site (SSWHS) launched a legal challenge to the Department of Transport about the lawfulness of their decision. SSWHS, which includes members of the longstanding Stonehenge Alliance, fundraised £50,000 from more than 2,000 people in 140 different countries to cover the legal fees. There will be a three-day High Court hearing from 23rd-25th June in which there will be a judicial review of the government’s decision to approve the road tunnel.

“To have won the arguments based on reason and evidence, and then to have them overruled on a ministerial whim, shows just how broken the roads approval process is,” Tom Holland, best-selling author and president of the Stonehenge Alliance, explains. “There is still a chance to stop the bulldozers moving in and vandalising our most precious and iconic prehistoric landscape.”

The Department for Transport published their reasons for building the tunnel back in November. Among them are removing the “notorious bottleneck” from the A303 road “which results in significant time delays and diversions onto less suitable roads.”Anybody that has visited Stonehenge, or lives in the area, will recognise this. The A303 runs from Basingstoke to Devon and passes just next to the monument. It’s a 93-mile dual carriageway that narrows into a single road when it passes Stonehenge and is often jammed with traffic. That skinny part of the road will become a footpath if the scheme goes ahead, with the tunnel being further South and, of course, underground.

“That road is an eyesore for anyone coming into the country,” says Janice Hassett, a local resident from the village of Shrewton. “They’ve come to see Stonehenge and they are gobsmacked when they see a busy road with traffic queuing right through the World Heritage Site.” Hassett founded the Stonehenge Traffic Action Group (STAG) in 2013 — a team of local residents and farmers that strongly support the road tunnel proposal.

“They come into the high street, which has no pavement; there are cob cottages that are getting ruined by all the traffic, we get litter thrown out and we get all the fumes from the traffic.”

Janice Hassett, local Wiltshire resident

STAG’s main aim is to reduce the rat running drivers that cut through the narrow streets of Shrewton and other villages in the area to avoid the busy A303. “All year round, and especially when the schools break up, it is horrendous in this village. There were 169,000 cars in August 2019, that’s just one road in Shrewton!”, she explains. “They come into the high street, which has no pavement; there are cob cottages that are getting ruined by all the traffic, we get litter thrown out and we get all the fumes from the traffic.” Hassett is 70, retired and regularly walks her dog out around Stonehenge. She tells me that people in Shrewton have been trying to do something about it for 30 years. The Department for Transport included this reason in its decision letter too.

David Bullock, the Highways England project manager, hones in on another big driving force behind the project: “It’s based around the transport link. Improving the whole A303 corridor, boosting the local economy throughout the whole South West by having a reliable route,” He says, adding:, “Productivity in the South West is 24 per cent below the national average. There’s an awful lot of suppressed economic growth within the South West. It is constrained by the transport links. You can’t move goods and services up and down that corridor very reliably. This is about the whole corridor, not just our project.”

Kate Freeman lives in Devizes, Wiltshire, 15 miles north of Stonehenge. She’s been fighting to protect Stonehenge for nearly 30 years as a campaigner for Friends of the Earth South West. “It is actually incredible that the Conservatives are prepared to do that when at the heart of conservatism is the word conserve. I think there’s going to be a lot of hard thinking,” she says. “People identify with [Stonehenge] very closely irrespective of their party allegiances, their religious allegiances or none at all. It’s something that uplifts people in all sorts of ways,” describing the move as a “political football”, with the Tory Party using the road tunnel in their 2014 election campaign to gain constituencies in the South West. I ask her how she’s feeling about her pending legal challenge: “Our hearts are in our mouths, actually,” she says. “This road tunnel is shocking and it breaks an international treaty.” She is referring to the UK’s obligation to protect the World Heritage Site thus protecting “common cultural heritage of humanity”.

Despite being a supporter of the road tunnel, archaeologist Mike Pitts, the editor of British Archaeology, describes to me on the phone that the WHS is actually much larger than the lines that currently define it. “That line, in terms of the Neolithic world, is completely arbitrary and meaningless! It’s a modern construct on both sides, defined by an existing road [A303] and not in reference to anything in the ancient landscape.”

Stonehenge has a complicated history. It was built around 2500 BC – the same time the pyramids of Ancient Egypt were built. There are many theories about who built it, ranging from the mythical wizard Merlin to a Greek Mycenaean prince to extraterrestrial aliens. “Even today, a lot of people think Stonehenge is connected to Druids,” archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson, professor at the Institute of Archaeology and University College London, explains. “But we are very certain from radon carbon dating that it happened before.”

Why it was built is perhaps the biggest bone of contention. There are theories that it’s a holy site, an ancient scientific observatory, a vintage concert hall, a place of healing or a place for burial. The construction of it has piqued the fascination of people for centuries too. The largest stone weighs a hefty 50 tons and, according to new research, the monument originally stood over 140 miles in the Preseli Hills in Wales. At some point it was arduously transported all the way to Wiltshire and nobody seems to know why.

Fast-forward a few thousand years and, after a big boom in tourism during the Victorian times, a fence was erected to keep people away from the stones in 1901. From then until 1964 the stone structures, or trilithons as they’re also known, were rearranged, re-erected and repositioned. Since 1964 it has been relatively untouched – aside from by the pagans, witches and curious tourists that visit it during the winter and summer solstices. It’s exclusively at these celestial events that the general public is allowed within 10 metres of the stones and many make the most of it by touching and hugging them.

Camping in the Salisbury Plain area has been disallowed since the heady days of Stonehenge Free Festival, which ran from 1972 until 1984. On the final event in 1984, 70,000 people came to dance, worship, be free and connect with the stones alongside like-minded folk. Following the festival, the National Trust and English Heritage appealed to the government for help regarding the mess left after the festival and the size it had grown to. The Conservative government happily vowed to put an end to it, with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher quoted as saying that she’d be “only too delighted to do anything we can to make life difficult for hippy convoys”. The following year, in 1985, the police descended on the site and attacked the van-dwelling New Age travellers that had arrived and ignored the festival “cancellation”. Aggressive officers set upon the self-described “peace convoy” with truncheons, dragging families apart, smashing up homes and battering anyone in their way. Four hundred and twenty were arrested and 12 were hospitalised in what became known as the Battle of the Beanfield. This was a sobering death knell of the Stonehenge Free Festival era and a harrowing reflection of Thatcher’s iron fist governance.

“English Heritage has transformed it into a museum piece, a caged creature,” says Indra Donfrancesco, from Glastonbury, during my visit to the Stonehenge Heritage Action Camp. “But for a lot of people, it’s a living temple, like St Paul’s or the Vatican.” This protest camp was set up in late December, nine days prior to my visit, in opposition of the road tunnel. After warily getting dropped off on the side of the busy A303 by a taxi, I am collected by Indra, an activist in her early 50s who has been involved in the climate movement since the ’90s. We walk through the icy white mist of an early January lunchtime towards the woodland south of the A303. Among the beech trees and hazel coppice, we come across the small but burgeoning community made up of two bell tents and a hand-built cabin made from tree branches, tarpaulin, hay and quilts. There are five residents there, along with a dog called Kelpy, two horses called Luna and Shandy, and a rescued ferret called Dusk. “I think there’s a change happening in our ways of thinking,” Luke, a protestor, tells me while feeding logs into a wood burner in the cabin. “A change in the way people want to live and interact with the planet and our neighbours and our communities.” The ex-tree surgeon goes on to say that the camps feel more important than the one-day protests for him. “There’s a growing number of people that are looking for it and need it. They need community.”

In the previously mentioned Journal of Architectural Conservation, Elizabeth Young wrote, “Stonehenge is far more important to more people than Twyford Down or the Newbury Bypass were.”

She was referring to two major checkpoints on the road protest timeline. The 1992 Twyford Down protest gathered hundreds in opposition to the extending of the M3 through the area in the southeast of Winchester. Protesters – led by a bohemian traveller group called The Dongas and later Friends of The Earth and other groups – climbed onto diggers and set up camps to stop the construction. The motorway was built, cutting directly through the down and destroying two Sites of Special Scientific Interest, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and two scheduled ancient monuments.

“I don’t hate all these people in high positions, I feel sorry for them because they’re just not awake. They’ve got their heads in the sand. They should be terrified for their children’s futures.”

Amelia, 22, protestor

The 1996 Newbury Bypass protest, which had been going strong since the ’80s, saw activists chain themselves to trees and dig tunnels as major tree-felling and undergrowth clearance began. Ten thousand trees were eventually cut down to make way for the road. The area of the Tot Hill camp, one of the biggest of the whole protest, is now a service station with a Shell Garage, a McDonald’s and a Starbucks.

This anti-road battle is very much still underway. At the protest camp, Amelia tells me, “I don’t hate all these people in high positions, I feel sorry for them because they’re just not awake. They’ve got their heads in the sand. They should be terrified for their children’s futures. I haven’t even got children and I’m scared, you know.”

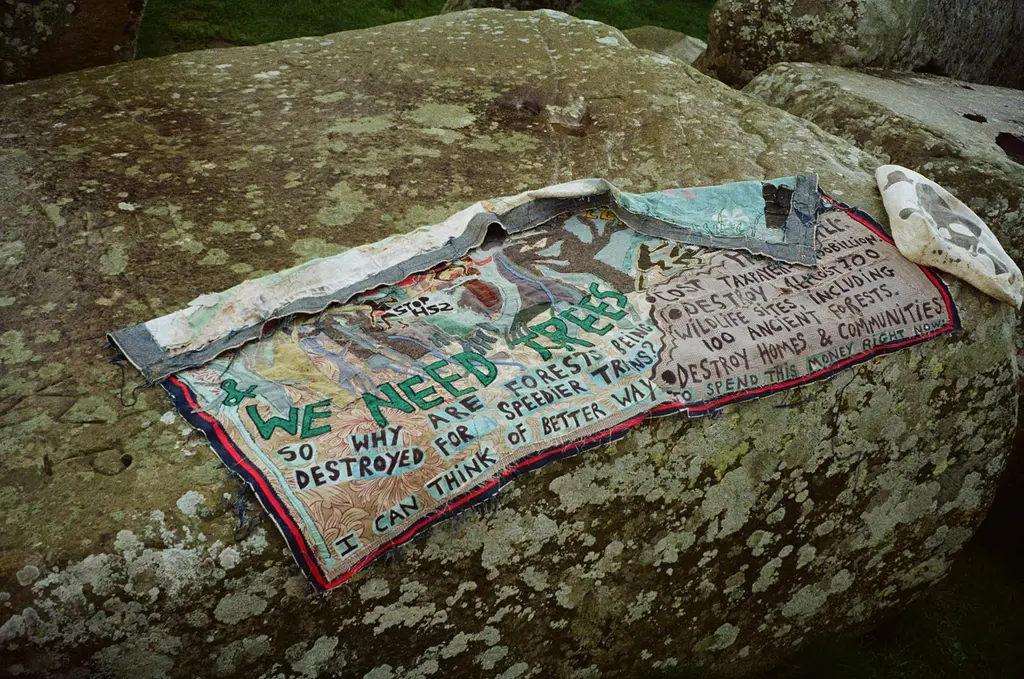

The residents I speak to have all migrated over from the HS2 camps and are dead set on living their beliefs every day, as opposed to dipping into climate protests as and when they can. “I’m just going to keep on living like this – resisting the system in this way,” Amelia explains. “I love this life; I wouldn’t wish for anything else.”

When it comes to the excavation of the WHS, even the archaeological world is split. Archaeologists Mike Pitts and Mike Parker Pearson have been friends since university and have both worked on digs together at Stonehenge. “There will be substantial excavations at the site before construction begins,” Pitts explains. “All paid for by the developers. This is very good. Most of the skilled excavations in the country take place in that context.” He goes on to explain that the very nature of archaeology is a destructive process. “There’s kind of a Faustian bargain with the past,” he adds. “When you excavate, you destroy.” On the contrary, On the contrary, Parker Pearson is firmly against the road tunnel and believes that the agency’s contractors will only be able to retrieve 4 per cent of artefacts in the ploughed soil during construction. “We are looking at losing about half a million artefacts – they will be machined off without recording,” he says.

Registered charity Wessex Archaeology has been hired as the archaeological specialists for the project and been awarded a £35 million contract to carry out “protection and excavation work” ahead of the construction.

Severely conflicting information is rife in this debate. The distrust for the government and for institutions such as the Department for Transport can be partly traced to old grievances related to their heavy-handedness during clashes with protestors through the ’80s and ’90s. David Bullock, from Highways England, admitted that one of their hardest jobs has been getting the correct information out there to the public about the project.

“There has been a huge amount of misinformation in this debate and I find that quite sad. Many people seem to think the stones themselves are under threat. There doesn’t seem to be any logic to it.”

Mike Pitts, archaeologist

Emotional voices often shout the loudest on social media and misleading information gets shared quicker than you can say “Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site”. Pitts explains: “What we know about social media is the stories that travel really well are not always entirely correct. There has been a huge amount of misinformation in this debate and I find that quite sad. Many people seem to think the stones themselves are under threat. There doesn’t seem to be any logic to it. There is no explanation as to why [the road tunnel] is actually happening. People are getting genuinely distressed and upset about it and that’s sad. It shouldn’t be like that. It’s a really difficult, complex issue and social media is notorious for not being able to handle complex issues.”

Everyone I interviewed agreed that building new roads brings more cars. One of the lessons we’re learning from the pandemic is that work travel isn’t as essential as we thought it was, with so many working from home and offices being shut nationwide. Furthermore, top scientists warned in January that our failure to grasp the threats posed by the climate crisis could be leading us to a “ghastly future of mass extinction, declining health and climate-disruption upheavals.” With this in mind, is the project tone-deaf and dangerous? Pitts doesn’t think so: “The pollution is worse now because vehicles are sitting in very slowly moving jams,” he says. “They’re constantly stopping and starting and running in low gears, so the emissions are higher. Once the road tunnel is done there will be an environmental gain.”

“They’ve got all this money for these fucking schemes, when they could put the money into something green that would return.”

Luke, protestor

Another thing to consider is that, after 10 years of Conservative austerity, along with the possibility that we’re edging towards a “double-dip” recession and the fact that the NHS in its “most precarious position in its history”, should these multi-billion road projects really be a priority to spend taxpayers’ money on? “They’ve got all this money for these fucking schemes, when they could put the money into something green that would return,” Luke explains back at the camp. “They could have tree-planting schemes where they employ 50,000 people nationwide for a couple of years to do it, so it’s made jobs too, instead of putting £130 billion into these road projects. Or they could hire another 50,000 nurses, or more, for the NHS!”

Whether your focus is local, environmental, economical, spiritual or archaeological, one thing is for sure: this is by no means a black-and-white issue. We will find out soon enough whether the road tunnel goes ahead or not. As our conversation comes to an end, Janice Hassett from Shrewton puts it quite lucidly as she says, “Whatever happens, I think it’s going to be a bumpy ride from here on in.”