The Italian seaside town that’s home to 150 trans women

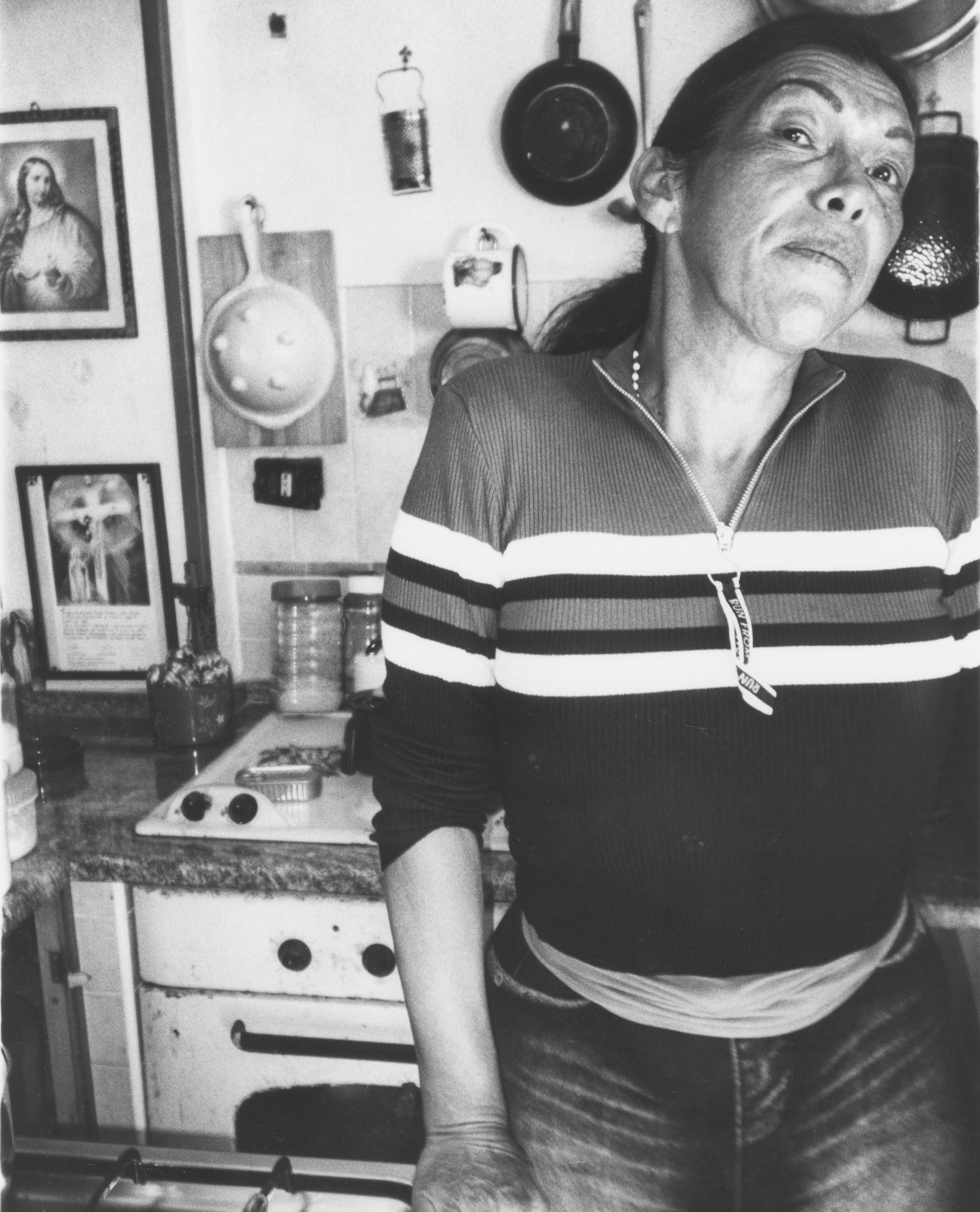

Daniela, 55, Argentina

Beneath the stillness of Torvajanica, Italy, a quiet revolution is unfolding among the region’s trans community – one small act of mercy at a time.

Society

Words: Naomi Accardi

Photography: Jesse Glazzard

Taken from the new print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

Father Andrea Conocchia first noticed them during the pandemic. The priest had been transferred to Torvajanica, a sleepy coastal town 30 minutes from Rome, just a few months earlier, when he became aware of a distinct group joining the queue for aid outside his rectory.

“At first, it was maybe six of them,” says the Father who, in his fifties, fits the description of a small-town Catholic priest to a T. He wears inexpensive glasses, speaks in a kind, monotone voice, and hand-spells the sign of the cross after every other sentence. “But as [word] spread, around 150 girls showed up.”

The 150 girls in question were all, improbably, trans women: all South American, many middle-aged, who had settled in Torvajanica and its surrounding areas over the last three decades. They’d come in search of cheaper, quieter living conditions and, as 52-year-old Uruguayan Marcela confessed during a meeting arranged by Father Conocchia, to be closer to their “office”: a large pine grove about 12 miles away.

Before crossing paths with Father Conocchia – or “Don Andrea”, as the women refer to him – their existence had largely been confined to the shadows, a necessary lifestyle choice given that most of them are sex workers. But with the pandemic abruptly shutting down their ability to make a living, the church became their only hope for survival. More than that, it became a bridge between their latent spirituality and the wider world.

Stretching for around five-and-a-half miles across the Roman littoral, Torvajanica is far from the idyllic Italian beach resort etched in popular imagination. Taking its name from Torre del Vajanico – a defensive tower built at the request of the Catholic Church in the 1500s to deter Saracen pirates – Torvajanica seems to be stuck in the 1990s, with quiet cafes, outdated facilities and a population of 17,000 that leans more toward perpetual snoozing than the glamour of la dolce vita.

But in the 1960s, the commune’s sandy dunes and proximity to Rome’s Cinecittà film studios had turned it into an unspoiled hideaway for visiting US film stars, such as Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Rome’s glamorous elite followed, as did the LGBTQ+ community, who found the area’s secluded nudist beaches to be a safe haven for those looking to live freely, away from the judgemental gaze of families. By the end of the 1980s, Torvajanica had acquired a reputation as a go-to spot for counterculture, with queer parties and raves taking place in the area. And while all that may be a distant memory from the lethargic, unassuming town I found myself in one October weekend, Torvajanica has continued to attract a community who wish to live freely, away from persecution.

Marcela, 52, Uruguay

Yuliana, 53, Colombia

The Torvajanica waterfront, as seen from Hotel Torvaianica on a chilly autumn morning

According to a study by Free Woman – a Rome-based NGO supporting foreign individuals who have escaped exploitation – approximately 40,000 trans women lived in Italy in 2010 (the most recent date for which figures are available). A quarter of them, 60 per cent of whom were from South America, survived by working on the street, just like the women in Torvajanica.

While up-to-date data is scarce, a more recent report by Escort Advisor (Europe’s largest sex work review and listing platform) suggests that trans prostitution in Italy is a £520 million-a-year business. Even when denied visibility and opportunity with legitimate jobs (sex work is legal, but brothels are not), these women continue to move an economy built on their exclusion.

But with exclusion comes danger. In Rome and adjacent areas, trans women working at night, along arterial roads or industrial peripheries, navigate not only the dangers of the street but also the prejudice of a culture that sees their existence as a transgression. It requires a resilience they’re long accustomed to: from parental violence and isolation from families in their home countries, to finding solidarity in informal safety networks and navigating a daily negotiation between acceptance and survival. In Torvajanica, though, via a priest willing to stand up for and by them, these women had found something else, too: a home.

Yuliana’s photographic archive. The top right image is a picture from her childhood

Coqui and Camilla are persuaded to talk to me by Don Andrea. Both are Peruvian, both show up at the parish at 10am sharp and both greet me with an embrace. There is a shyness about them, but they seem eager to tell their stories. Coqui, a solidly built 70-year-old who has been living in Italy for 35 years, wears a patterned maxi dress with a sleeveless black puffer jacket. Camilla, 44, petite and softly spoken, opts for a grey tracksuit and sharp black eyeliner paired with hot-pink shadow.

“I arrived in Italy as a man in 2008,” Camilla says, calmly and with unwavering eye contact. “I wanted to transition in Europe, because at the time it was easier than in Peru.” She was once in a relationship with a man from Brescia, but the romance didn’t last and she moved to France before finding her way back to Rome. There, she met another man, who she married and stayed with until the relationship petered out. “We aren’t divorced. We still have a great friendship, but our love declined,” she says with the wistfulness of a teenage girl reminiscing about her first love.

Coqui arrived in Italy in 1990 after fleeing the political instability of their home country. She discovered a culture of warmth and conviviality that felt similar to the Peru she remembered. Still, she had to resort to prostitution to survive. Eventually, she also found love and marriage. I ask how her husband, a Neapolitan, swept her off her feet, but she’s quick to correct me: “I swept him off his! I used to live close to the Stadium [Olimpico] in Rome. He was following his club on an away match and we fell in love.” Every other Sunday, Coqui hosts a supper that tastes like home for her South American guests: empanadas, papas a la huancaína (potatoes in a cheese sauce with peppers), ceviche and other nostalgic flavours, all shared by around 10 women who come to find solace despite the hardships of their everyday lives.

Coqui and Camilla were part of the first group of trans women that Don Andrea sought to help. “It all started after meeting them and listening to their stories,” he tells me of their introductory encounters during the first lockdown of spring 2020. Due to their profession and status as trans women, they explained that many felt marginalised and disconnected from the church, unable to practise their faith. Their only help, they felt, was to appeal to Catholicism’s highest authority. “So I reached out to a friend, Sister Genevieve, who at the time was very close to the late Pope Francis,” says Don Andrea. “I asked her if it would be possible for these women to send him a letter.” In 2022, Pope Francis responded with an invitation to the Vatican. “I was religious before,” says Camilla, “but I didn’t believe in the church because it had always excluded us. After meeting the Pope, my faith was renewed.”

Claudia Valentina, 44, Argentina

Yuliana playing with her kitten, Zeus

Starting in April of that year, at the request of Pope Francis, Don Andrea organised weekly field trips to the Vatican for the women. The initiative was a tangible reflection of the Catholic leader’s inclusive vision – one rooted in compassion rather than condemnation. In a now-famous 2013 address, he had declared that: “The Church, which is holy, does not reject sinners… it calls every- one to let themselves be embraced by the mercy, tenderness and forgiveness.” It was a statement that marked a quiet revolution within Catholicism, signalling a shift toward openness and a pastoral empathy that was unprecedented among his predecessors (and which appears, at least, to be continued by his successor Pope Leo XIV).

Coqui and Camilla are far from the only beneficiaries of this embrace. We hop in Don Andrea’s car and drive for 15 minutes to a dishevelled complex that’s a ballroom, restaurant, bowling alley and motel all at once. Claudia, 58, who is from Argentina and has been employed here as a cleaner for the past six years, is waiting inside the bar, alone at a table. She’s short, has honey-blonde hair and blue contacts, and is wearing a matching turquoise neck scarf.

“I first landed in Spain from Argentina, then I went to France. But French people are assholes, so I came to Italy,” she says with a smile. “Italian people helped me a lot.” She shows me around the ballroom, explaining every little detail about the place as if she owns it. If a chair is out of place, she fixes it. Clearly, she is proud of her work.

As we move through the large room, she tells me about the motel’s owner, Maria, who gave her another chance at life by providing her with a job – a 23-year resident of Torvajanica, Claudia is now retired from sex work. “This is my home,” she affirms. “I don’t need to travel back to Argentina. My father was the only one who accepted me for me, but he died. Maria, la patrona,” she switches from Italian to Spanish, “is my mother now.” Her eyes well up. Then she points outside. “The street is the best school. It teaches you who is really your friend, your family.”

The entrance of Torvajanica’s Parrocchia Beata Vergine Immacolata church

Consuelo, 65, Colombia

As Don Andrea tells me back at the rectory, “these women grew up in extremely religious environments. Just like [in] Italy, their families instilled this deep spiritual belief in them that has not left, even after they came out as trans and faced serious threats to their lives.”

He introduces me to a visitor, Yuliana – or, as she likes to be called, Cleopatra Carter. Born in Bucaramanga in Colombia in 1972, Yuliana tells me she was put on this planet to be a star. And in fairness, her presence is as intoxicating as her features are delicate.

Abandoned by her mother and raised by her grandparents, Yuliana de- scribes how she was born again in the capital Bogotá’s nightlife scene, each tale acted out like a piece of theatre, her long black ponytail whipping around dramatically. “I used to come home at 4am every other night, and my mother wasn’t happy. So I left. That’s when I discovered I could work on the street and make a lot of money.”

Yuliana joined a high-end club attended by the Colombian elite. “It was amazing at the beginning,” she says, smiling. “Clients were screened, only rich men with big cars came.” After a couple of years, she went freelance. “Every night I had a row of luxury cars lining up to pick me up. I was beautiful, tall, slim, with clothing I designed myself. Men would pledge more money than the one before to sleep with me!” At 53, she still turns heads.

“Then one night,” Yuliana’s voice drops, “I was with a wealthy man who told me it’s no different from being with a regular woman.” She was offended, and let a girlfriend named Lucero – “who regularly stole from clients” – help enact her revenge. “As the man dropped me off, Lucero asked me to leave the door [to his house] open and I did. She stole his jewellery and a stack of cash.”

Several months later, a car pulled over as Yuliana walked the streets. An angel-like vision emerged, draped in a white dress, glowing under the streetlights. It was Lucero, back from hiding to thank her. “She bought me a ticket to Italy,” Yuliana says of the night that began her new life in Europe.

This was June 1995 and Yuliana was ready for her adventure. “The journey was long. Bogotá to Caracas [in Venezuela], then Prague. We were stopped and questioned at customs in Prague, but Lucero had a plan: she said we were going to see the Pope and they let us go.” Based out of Rome, Yuliana’s beauty and confidence took her across Europe as a dancer and entertainer. In her flat she hands me a pile of photos pulled from a stored suitcase, evocative of a time, she says, when being trans was accepted as a curiosity and trans women were a hot commodity. “In the 2000s, it was new!” she says with a laugh.

Claudia, 58, Argentina

Photos in Don Andrea’s study room. The top two images picture him on the day he was sworn into the Catholic Church

Camilla, 44, Peru

Coqui, 70, Peru

As the day draws on, Don Andrea drives us to meet Consuelo at her home, a small, humid shed right on the beach, the sun beating through its roof. The space is small, dark and moist, with mould creeping on the ceiling. But Consuelo is house-proud. At the stove, she’s frying arepas, the cornmeal bread typical of Colombia, where she’s from. She hands me one with a cup of strong coffee. At 65, Consuelo is one of the oldest trans women in the area, making her a reference point and source of invaluable local knowledge for new arrivals. A rosary peeks out from under her sweater, while a pair of faded jeggings accentuates her figure.

“I escaped from the jungle and came straight to Rome,” she says. “I landed in Torvajanica because of a client who took me to a hotel here.” Like many other aging trans sex workers, Consuelo now works part-time as a carer for the elderly, one of the few jobs that doesn’t discriminate against age, gender or immigration status. “It’s something that has helped me make ends meet,” she says. She’s also currently hosting a younger trans girl, a sex worker, who arrived eight months ago from Bogotà. Without shame, she lets me know that the girl’s work helps to pay the bills, in a sort of madam-charge relationship. But it’s still not enough. To subsidise some of their living costs, Consuelo has recently asked for financial aid from the Pope’s office, a practice that was introduced to her by Don Andrea.

As I step out of Consuelo’s small home and back onto the quiet beach, the sea stretches out the same as before. But Torvajanica no longer feels asleep. Beneath its stillness, I can see that a quiet revolution is unfolding: a small town where a humble priest has had the bravery to break free from conservative teachings and welcome one of Italy’s most marginalised groups into his house. For the trans women living in the Torvajanica area, the Church is no longer a place to hide from, but a refuge through which they can seek comfort.

I think of Consuelo and the way she pointed at the many pictures of Jesus on her wall. “It’s him who gifted me this attitude,” she had said. “It is God who gives me the power to keep going.”