LVMH Prize winner Thebe Magugu: “The world is finally keeping up with Africa”

The South African designer tells us about his homespun, high tech AW20 collection.

Style

Words: Sarah Moroz

On Wednesday, South African designer Thebe Magugu presented his AW20 collection within the bowels of the cavernous Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

It was only last year that Kimberley-born, Johannesburg-based Magugu became the first designer from the African continent to win the LVMH Prize, a Holy Grail for young designers that provides financial support to the tune of €300,000, plus a 12-month mentorship boost from the LVMH group (the luxury-good conglomerate that owns Celine, Dior, Loewe and Louis Vuitton, among others).

Magugu’s presentation-cum-exhibition, however, betrayed none of the windfall and none of the bravado that might be expected in the wake of the prize: the venue was modest with peeling ceilings and dim lighting (it was the basement of the Palais de Tokyo but it was still a basement), while Magugu’s demeanour was warm and earnest.

“It’s so difficult to present this in a fashion show setting,” he said of his decision to show the collection away from the traditional runway. “I wanted to create an exhibition space where you’re forced to consider what’s around you. You can look at the work, instead of it zipping by within ten minutes.”

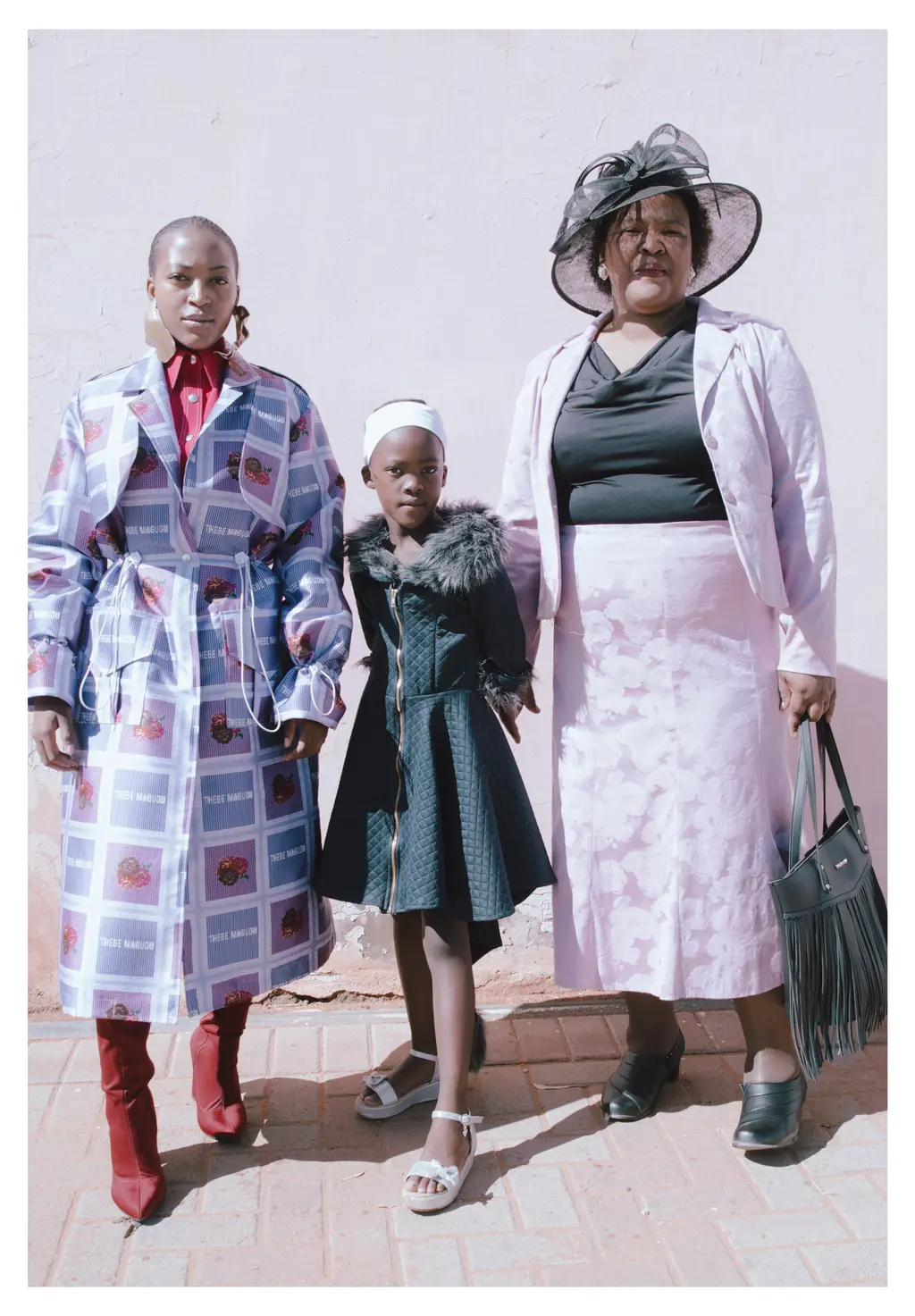

The presentation included two sets of five photographs, shot by fellow South African Kristin-Lee Moolman and styled by Ibrahim Kamara. Sitting before an accompanying video were ten masked mannequins, scattered over three rows of white fold-out chairs.

Although Magugu has relished his newfound access to pillars of the industry, namely the thrill of chatting with Anna Wintour (“I grew up watching her, so it feels full-circle”), winning the LVMH Prize has not ultimately reshaped his approach or made him greedy for global domination. Sure, he’d love Rihanna and Beyoncé to wear his clothes. But that hasn’t prevented him from doubling down and embracing his roots.

For AW20, Magugu harnessed his love for his hometown and the setting that shaped him. The collection was titled IPOPENG EXT. Anthro 1 after the township he grew up in, while one of the photographs displayed in the presentation was shot in his mother’s living room. Another featured his uncle on a motorbike. “All this sort of funnels into the collection: as references and prints and cues,” he said.

He described the collection as “elevated casual” and – fittingly – the entire work was created in South Africa. His grab bag of references includes pleating, sharp tailoring, uniforms, and Sunday Best. A leather garment was emblazoned with the label’s “sisterhood” iconography, stitched and braided by hand; his grandmother’s kitchen tablecloth was reimagined as a utilitarian parka; and his aunt’s corrugated iron fence translated into a grainy crepe textile.

While effectively homegrown and low-maintenance, Magugu has also integrated a cutting-edge tech component into each piece. Every garment is chipped, which – via an app – provides complete access to pragmatic details: the composition of materials, the address of the supplier, biographies of the people who sewed the garment. It also reveals a more elaborate personal narrative (including essays penned by Magugu, who is fond of writing) and companion “recommended reading” lists that informed the designers research. Transparency is of the essence to him, and the chip works as a communication channel.

“At the end of the day, it’s just a pretty coat,” Magugu says. But he’s glad there’s room to make it more: “Now you can get into my thinking as well.”

Creating a story beyond the silhouettes themselves is something Magugu has always been keen on: every September, he publishes a zine, Faculty Press, which gathers together a coterie of creatives “who challenge really tired stereotypes about South Africa”. He found that people had a one-dimensional view of the multiplicity and creativity on the continent, and he wanted to offer a counterpoint.

“People often tell me ‘your work doesn’t really look African.’ They have this print-heavy reference.” But, he counters, “By virtue of being from Africa, my work will always be African, because these are my experiences. I grew up with traditions, but I also grew up with the internet and a globalized world, and obviously I reflect that.” For westerners to think that this versatile cross-pollination is novel is, at best, misguided.

“Let me say: it’s just that the world’s global eyes are looking at Africa and saying ‘Oh, all these new things are coming from there.’ But those things have been happening for quite some time. It’s not Africa keeping up with the rest of the world, but the world finally keeping up with Africa.”