Ari Marcopoulos: “Everything is worthy of a photograph”

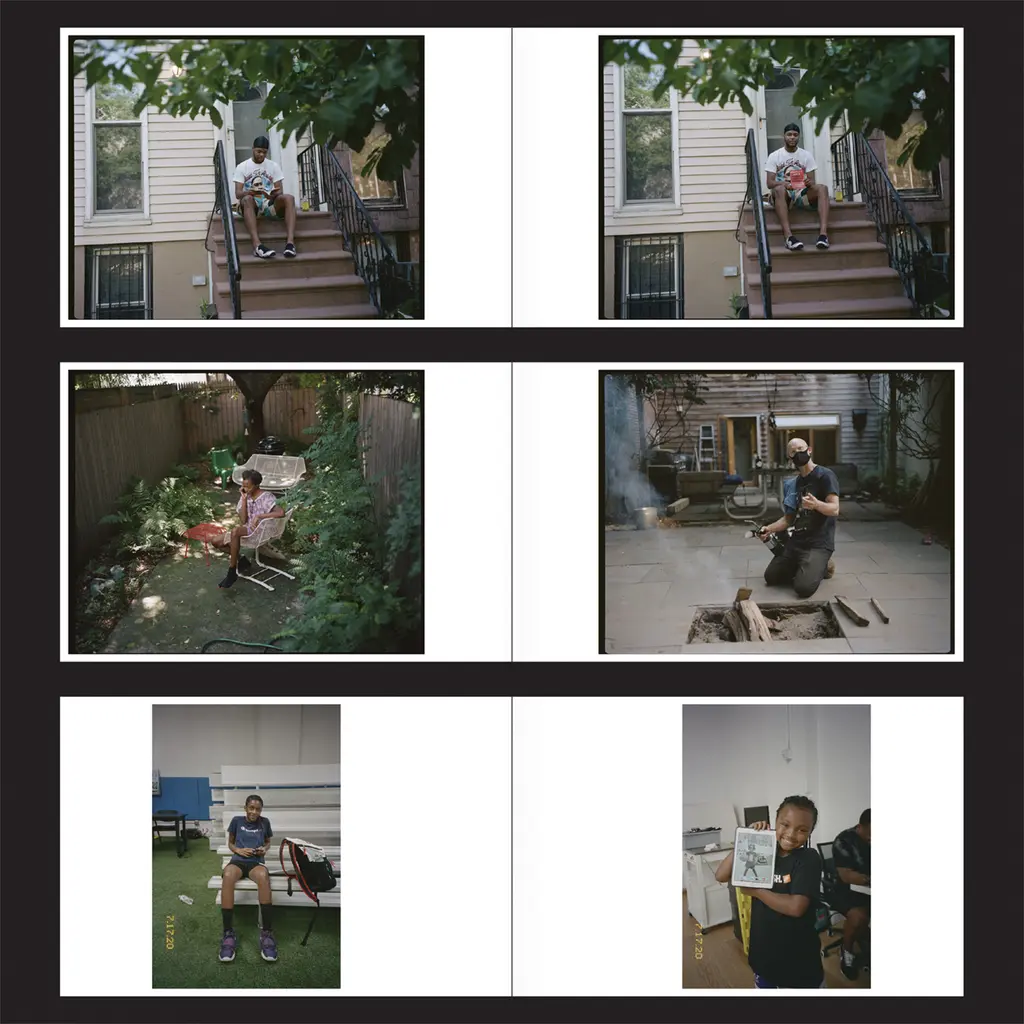

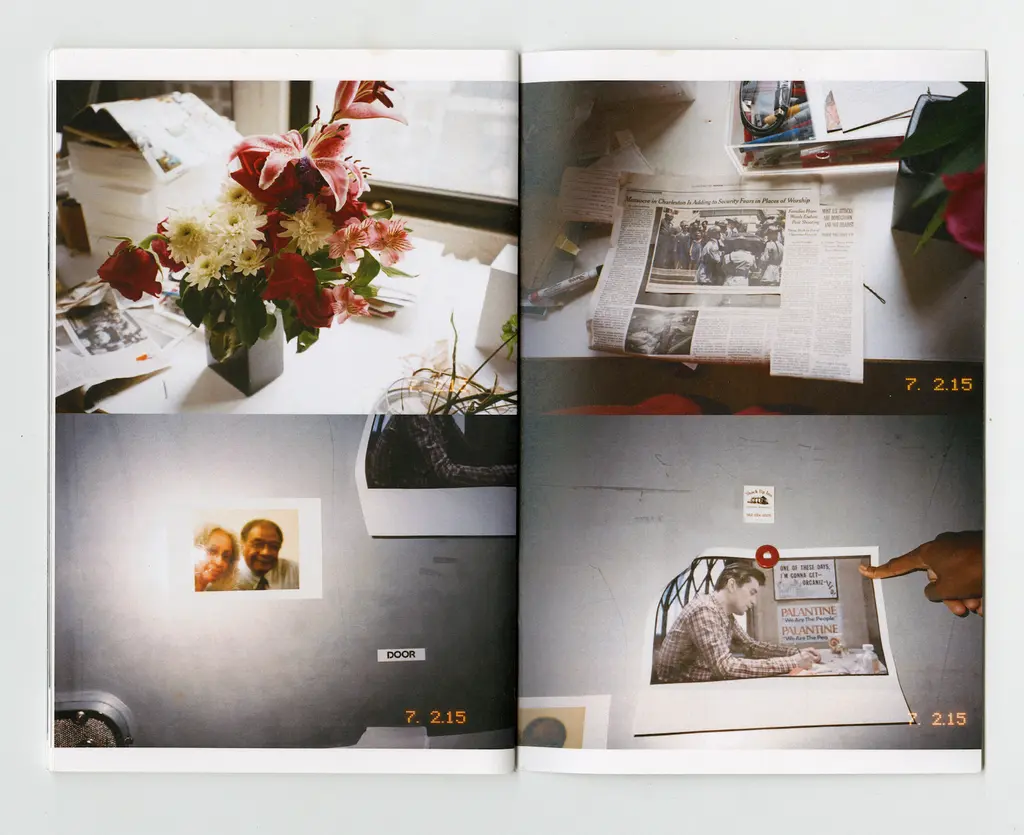

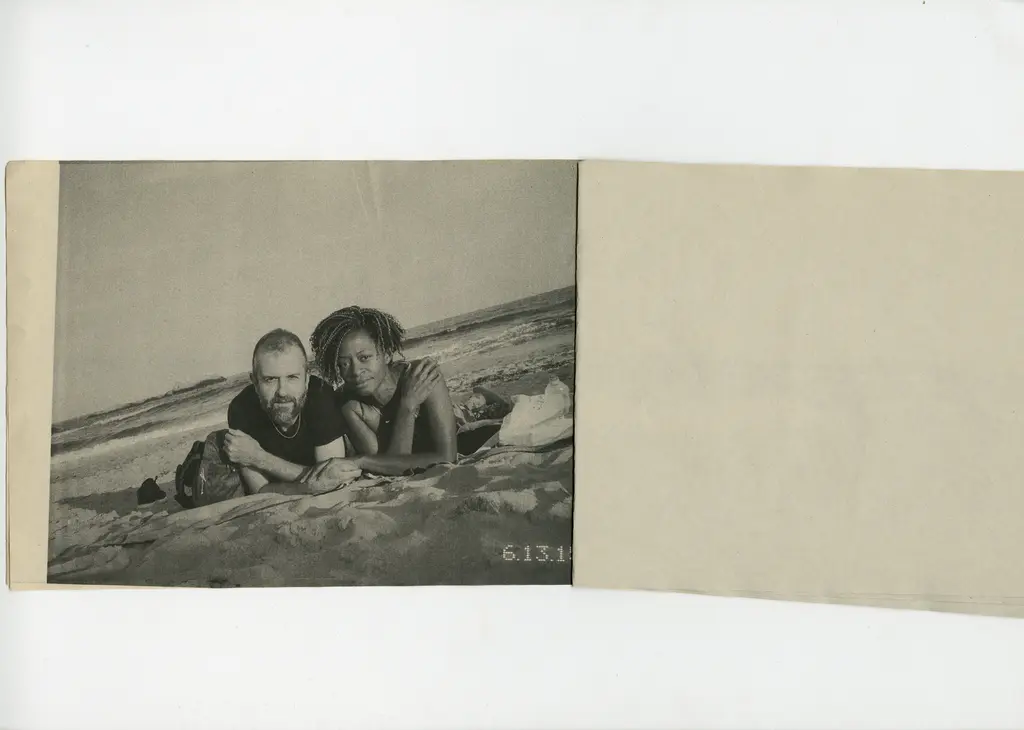

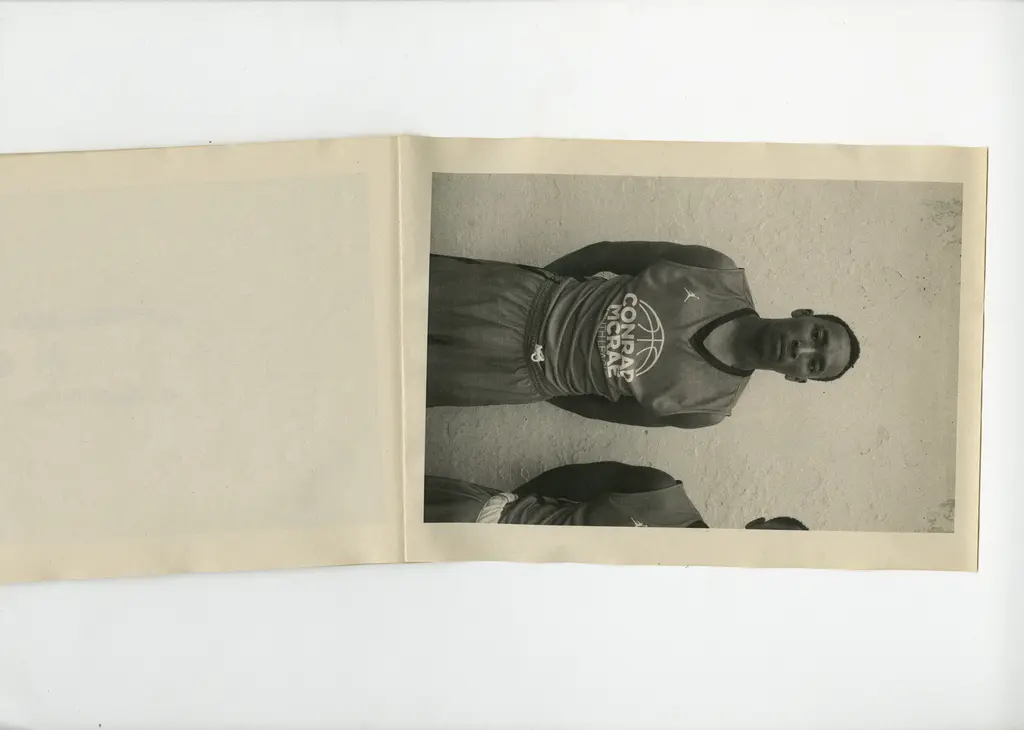

The legendary New York photographer’s latest book Zines is a cinematic snapshot of the city from 2015 to 2019, told through his raw, unfiltered style.

Ari Marcopoulos has been at the centre of New York’s counterculture scene since he left his native Amsterdam in 1980 at 23 years old. He’s worked for Andy Warhol and Irving Penn, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Robert Mapplethorpe. And he photographed some of the most recognisable (and legendary) faces of NYC hip-hop during the ’80s and ’90s: Public Enemy, Rakim, LL Cool J and The Beastie Boys, to name but a few.

It’s safe to say he’s witnessed New York youth culture blossom. Marcopoulos was there during the early beginnings of New York’s underground skate scene, for instance, when insiders flocked to a little-known shop-cum-cultural hub on Lafayette Street called Supreme.

“Perhaps it’s the most famous city in the world, I don’t know,” the 66-year-old photographer says with an air of irreverence. “When I moved here, I was certainly very attracted to the idea of moving to New York. Now, it’s my home and I have a very hard time imagining living somewhere else. It’s a very inspiring place to be.” Like most New Yorkers, you get the feeling Marcopoulos is fiercely loyal about his home turf.

The restless city, its hardcore grind, shapeshifting styles and DIY attitude, has been the backdrop of his work for four decades. Now, his documentary photography from 2015 to 2019 has been compiled into Zines. Compiled like a family photo album and inspired by his affinity for fanzines, which he started collecting in the early-’90s, Zines is as much a scrapbook of Marcopoulos’ life as it is a time-capsule of New York.

“I feel like this book is very cinematic,” Marcopoulos says of the bumper book that boast more than 300 pages. “It’s more of a movie than a photo book.”

Hey, Ari! What’s the first zine you remember buying?

It wasn’t really a question of buying zines back then, people were giving them out. There must have been a point where I bought a zine, but I think in the beginning, it was more finding them somewhere. I remember [influential skateboarder] Mark Gonzales giving me zines, possibly in the early ’90s, mostly about skateboarding or music.

In simple terms, zines are about passing on information – new ideas, new styles, new people – like magazines and, to a lesser extent, books. What makes a zine special to you compared to other mediums?

With books and magazines, there’s a lot more production involved as far as the [idea] being conceived and then made. And often in magazines, there are multiple opinions. A lot of zines are fanzines, so there’s a real passion. You get this point of view of somebody that might not be well-known, or you have an opportunity to find something very unique and very personal. And people usually don’t make more than 25 copies of a zine.

That DIY side of zine-making feels quite rare now, doesn’t it?

Zines have taken on a much bigger role with art fairs and things that are happening, where people print more copies – it has become a little bit more of a business than it used to be. The idea back then was that if you couldn’t find the types of images or information [you wanted] inside magazines or books that were out there, you would make something that shows what you’re seeing or feeling. That’s what makes zines unique – you can make one at home. I guess now it’s even easier with computers and software. But back in the day, you would cut out photographs, glue them on paper, put them on a Xerox machine back to back and then staple them. There was very much a DIY, handmade aspect to making them.

With social media, they’re becoming more rare now, since we’re documenting thoughts and images everyday, from our phones. Your book is very much your point of view – the things you come across everyday, like a photo diary. Do you see it like that?

Well, whether it’s a diary or not, people tend to look at my work and say, “Oh, yeah, it’s a diary, you see his partner, his children, his friends.” And the dates on the pictures give the feel of a diary. But it’s not really a diary, because I feel, in a way, you don’t get to see so much of my life. It’s not like I’m trying to show you what my life is like, or what I’m doing. They are more images that I feel people can relate to, because they have similar situations. There are photos in there that I would say are amazing photographs, but maybe something funny is happening at home and people can look at it and it reminds them of their own lives. You also get an idea of what I look at and what fascinates me, or what I’m interested in.

You can really sense that fascination with your subject matters – whether they’re friends, family or strangers on the street – and your style is pretty raw and unpolished. Who have been some of your influences over time?

In my teenage years, I started going to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Amsterdam. I saw an early show by Nam June Paik and a show by James Terrell. Those things really baffled me, as it broke a certain barrier of what I thought could be art. It opened my eyes to expressing one’s ideas in a myriad of ways. And then I started seeing films by [Pier Paolo] Pasolini and [Rainer Werner] Fassbender, and American movies in the ’70s like French Connection. And then photographers like Diana Arbus and Robert Frank. All photography started becoming interesting to me. I would also look at sports photographs of American basketball – I played basketball when I was a kid. To make a list of names becomes very tricky, because you either leave someone out, or the list becomes huge.

What makes a subject or photograph print-worthy when you’re editing so many down for a book?

Everything is worthy of a photograph. There’s probably a fair amount of photographs of trees in the book, so I guess I love trees – but who doesn’t?! As I move through my life, I see things and I’ll photograph them because they catch my eye. If you walk around with me, then I would talk about things that I’m seeing, not necessarily even photographing them, but I will be pointing out things to you. I see many things that I think would make a fascinating picture, and I don’t always take a photograph of it. It goes in spurts.

You’ve been at the centre of New York counterculture for a long time. How have you seen the scenes evolve over time?

There’s no denying that New York is a city that attracts people from all over the place: tourists, artists, old people, young people, immigrants, people looking for work. There’s a lot of aspects to New York that you might not see if you’re here for a short visit. Of course, there is always a lot happening. A lot of people talk about gentrification, but I think that is something that is kind of international. The core of New York is that it is a city where people live and where people have to work hard, and those people are still here. You see those people every day on the subway, in the street.

How has gentrification affected the art scene?

There are still a lot of young artists here working and doing things – some of them are seen and some of them are not seen. There’s still plenty of experimental music, people putting out zines. A lot of the artists have moved further out from the centre of New York because of gentrification, but they’re still here. I can’t say that I’m so in touch with that – I know of things happening, but I never really go out looking for the newest shit that’s going on. I just follow my own path and things that I happen to walk into.

Ari Marcopoulos’ Zines is available to purchase at aperture.org (£65)