The mundane yet surreal world of Ed Atkins

It’s a big week for the writer, artist and filmmaker: there’s a retrospective of his work on at the Tate Britain, and he’s got a new book out, Flower. In both, he asks himself – and the audience – big questions about modern life.

Culture

Words: Lauren Cochrane

Open Ed Atkins’s new book Flower at random, and you might come across any number of things: an anecdote about how he wet himself on a school trip, an appreciation of bleaching the kitchen counter, an assertion that his ancestors were all dildos.

This surreal, mundane and confessional collection is just a small sample of the world that the artist and writer has come to know since he started working around 15 years ago; it’s a world that exists in Flower but also at the Tate Britain, where a major retrospective of his work opened this week.

Via video pieces, biro drawings and wonky CGI animations of, say, a phone call between him and his mum but also a man masturbating, Atkins zooms right in on the minutiae, absurdities, slop and emotion of modern life, asking you to confront it all. Similar to the experience of watching someone squeezing blackheads on YouTube, it’s squirm-inducing, but you can’t look away.

Atkins’s work is not easy. Flower, for example, is 89 pages long, but it’s only one paragraph. English Lit students might see it as an update on James Joyce’s famously unreadable novel Finnegans Wake (1924 – 39). Like Joyce, Atkins is not afraid to show you the sad bits of life: there’s the Tate’s Nurses Come and Go, But None for Me, a two-hour feature film starring Toby Jones, who reads the diaries of Atkins’s dad, which he wrote in the last six months of his life. But there are also the joys, such as self-portraits Atkins printed on 700 Post-Its. You’ll also learn about his love for corner shop wraps in Flower. A lot to unpack, right? Fear not: we sat down with Atkins himself to ask what he makes of, you know, life.

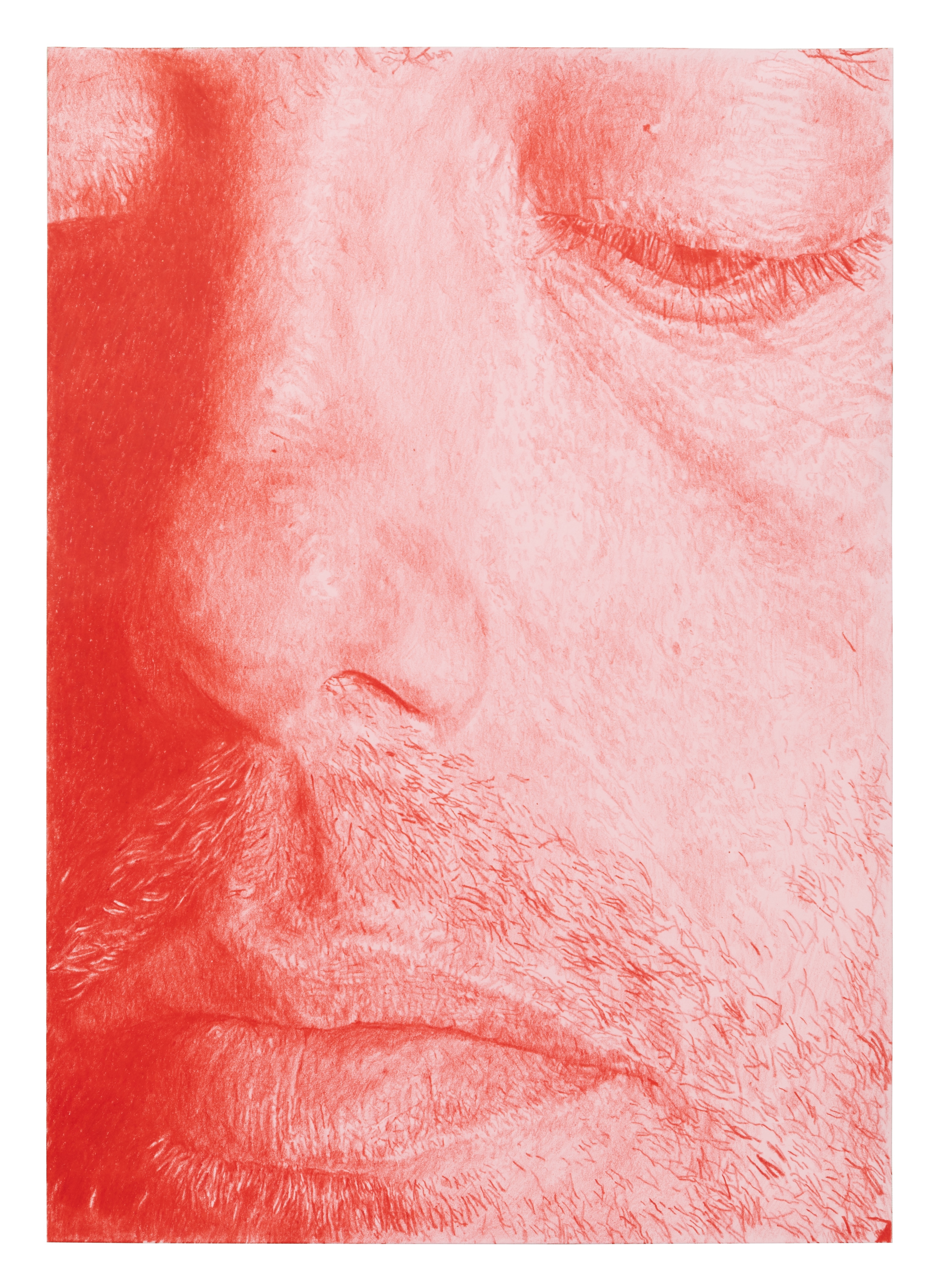

Pianowork 2, 2023

Hi, Ed. You’re a writer, an artist, a filmmaker. What do you think of yourself as the most?

If I’m feeling naughty, I think of myself as a writer first and foremost, or at least someone who’s most interested in language. I’m trying to test the limits of what life is, in terms of its depictions. And I use my own to do that. So it’s putting myself, or what I think of as myself, through a kind of ringer to try and test it. Often, that comes about perversely, through using artificial means – like something that’s obviously computer-generated.

Do you use tech as a foil to protect yourself in some way?

I could say everything that I thought I knew about myself [in my art] and still feel sort of irrecuperable, like it can’t be had. However good the fidelity of a CG thing is, it will never be as good, it will never be a person. Flower, for example, is kind of a memoir, but it’s a bit ludicrous. I’m excited that it gets shelved next to much more normal works. It’s fraught with fictions and worries and a lot of extreme banality.

How would you describe Flower?

It’s a type of self-portrait. There’s this Joe Brainard book called I Remember [1970]. He was adjacent to the language poets in New York in the ’80s [a group who aimed to deconstruct what a poem actually is]. It’s his most famous book and every sentence begins with “I remember”, and it’s just things he remembers. Cumulatively, it has this extraordinary effect of building something, a picture of a life. It’s profound in its tiny observations, which wouldn’t usually merit being recorded in some way.

Why does this appeal to you?

My inclination is often to go for discarded things or the situations that don’t normally merit any kind of attention – like throwing a lot of expensive animation at a phone call with my mum [in 2021 film The Worm]. Most of our lives are quite boring, but still poignant or beautiful. In Flower, I wanted to engage with what would never usually be described as literature, like comment forums and stuff – bad writing that is excessive in one way and completely impoverished in another, flat or hysterical. I really wanted it to feel unmooring.

Nurses Come and Go But None For Me, 2025

Nurses Come and Go But None For Me, 2025

There’s a bit in Flower where you send a text to yourself to demonstrate the stimulation we’re constantly craving. Are we addicted to our phones?

There’s an unconsciousness to it. Life is almost always [happening] while holding this thing. Or it’s also having a certain kind of brain that likes to have a lot going on at the same time. There’s a scene in the book where I am watching something with one earbud in so I can hear the kids if they wake up, while also trying to write, while also playing a game, and drinking heavily. It’s this scene of ecstatic nothing, which is very common.

I read in an interview that you don’t necessarily need people to “get” your art. Is comprehension overrated?

There’s an idea that art and, by extension, certain kinds of literary forms, are only understandable if you point away from them and say “Well, it’s about this.” And then the thing that it’s actually about starts to swallow up the need for the thing to exist… Ambiguous and ambivalent are my favourite places to be in. I am ambivalent about what or who I am… I don’t really know – desires shift all the time. It’s very confusing to be alive.

In Flower, you mention that you’re a super-recogniser. Give us an example…

I’m always so confident about someone who’s 1,000 yards away, I can point them out from any angle. Faces are everywhere in the work. I did some tests online and apparently, it’s true! But they’re almost certainly not really true. It was a bit like ADHD – I was like, “Oh, maybe I’ve got that as well.” That’s what self-diagnosis does.

I was struck by how raw and emotional Flower was, especially after the post-Adolescence debate about young men suppressing their emotions. Is that tone a conscious thing?

I haven’t seen Adolescence – I’m one of those people that will avoid something that everyone’s looking at – but I’m aware of mainstream discourse and contemporary problems around masculinity. I don’t mean to sound pretentious, but I don’t think about it in terms of contributing to a discourse. Part of my ambivalence is in all of the structures to do with being a man. I don’t necessarily identify like that. My personal identity is in flux and, as a father, I’m trying very hard not to be a man because I don’t want to just reinforce or reiterate anything.

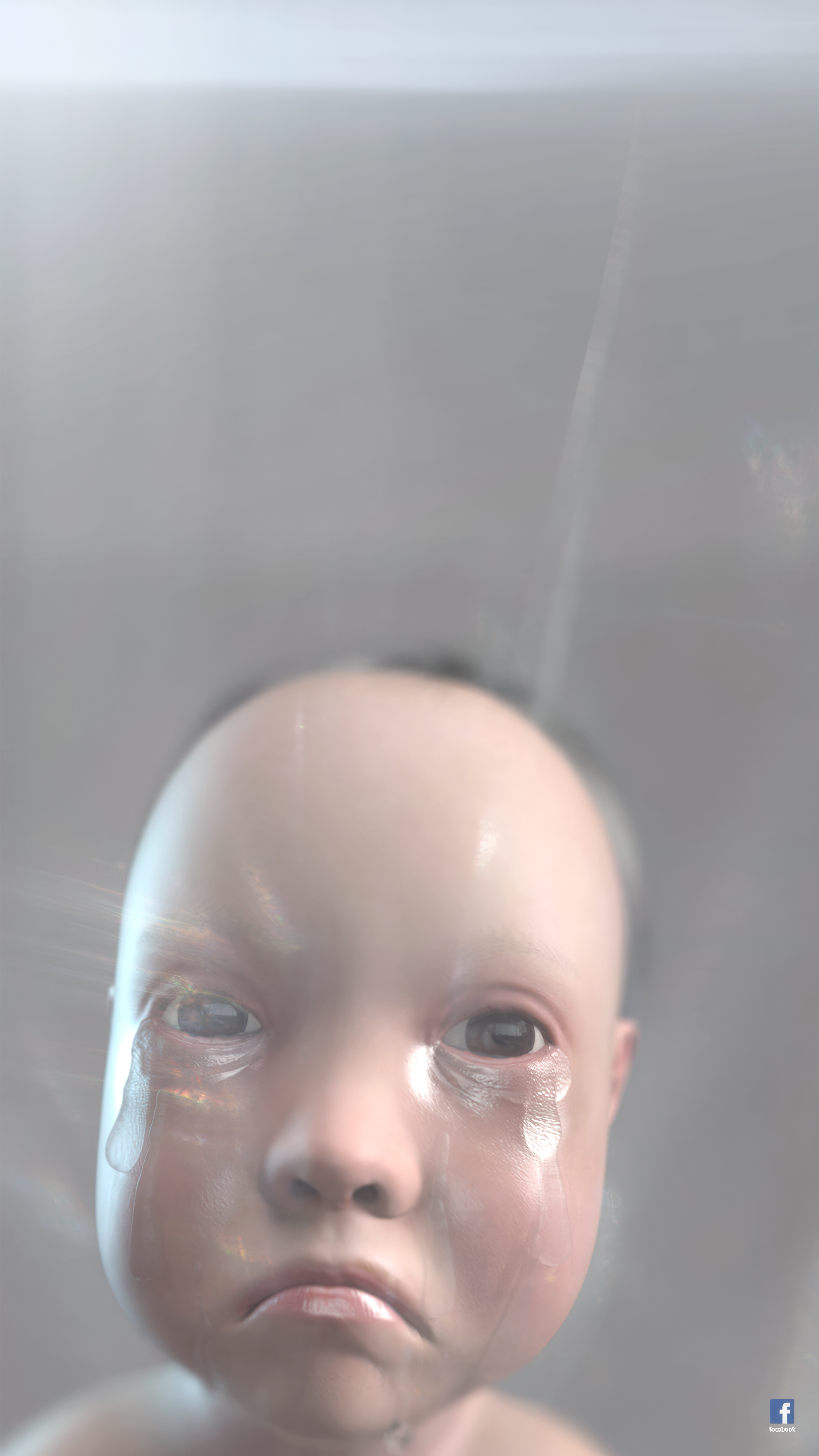

Good Baby, 2017

Untitled, 2023

Children, 2020

The Worm, 2021

Working with your own father’s diaries must have been hard.

It’s a bit much, you know? It was a lot to make, but it was a joy as well. It’s the first time working with a proper film crew. We read the entire diary to a group of young people, and [the actors Toby Jones and Saskia Reeves] did a version of a game I used to play with my daughter, role-playing an ambulance driver and patient. In the diary, there’s someone struggling to believe that this is happening to him. Right up until days before the diary ends, he’s still asking, “When does one begin to think about dying?”

Where does the book’s name come from?

I loved the idea of it being a thing. You can give a flower. “Oh have you got a flower?” “Here’s a flower.” It fits into some peculiar history too, as with Les Fleurs du Mal [The Flowers of Evil, the 1857 book by poet Charles Baudelaire]. It’s this motif of something that’s dead but beautiful. The text block thing was also part of that – to try and turn it into an object.

So: is Flower difficult to read on purpose?

Sort of, but it’s also like scrolling. You just keep going down, down, down…

This way for Flower and this way for Ed’s Tate Britain retrospective