When do you stop being a girl, and who gets to decide?

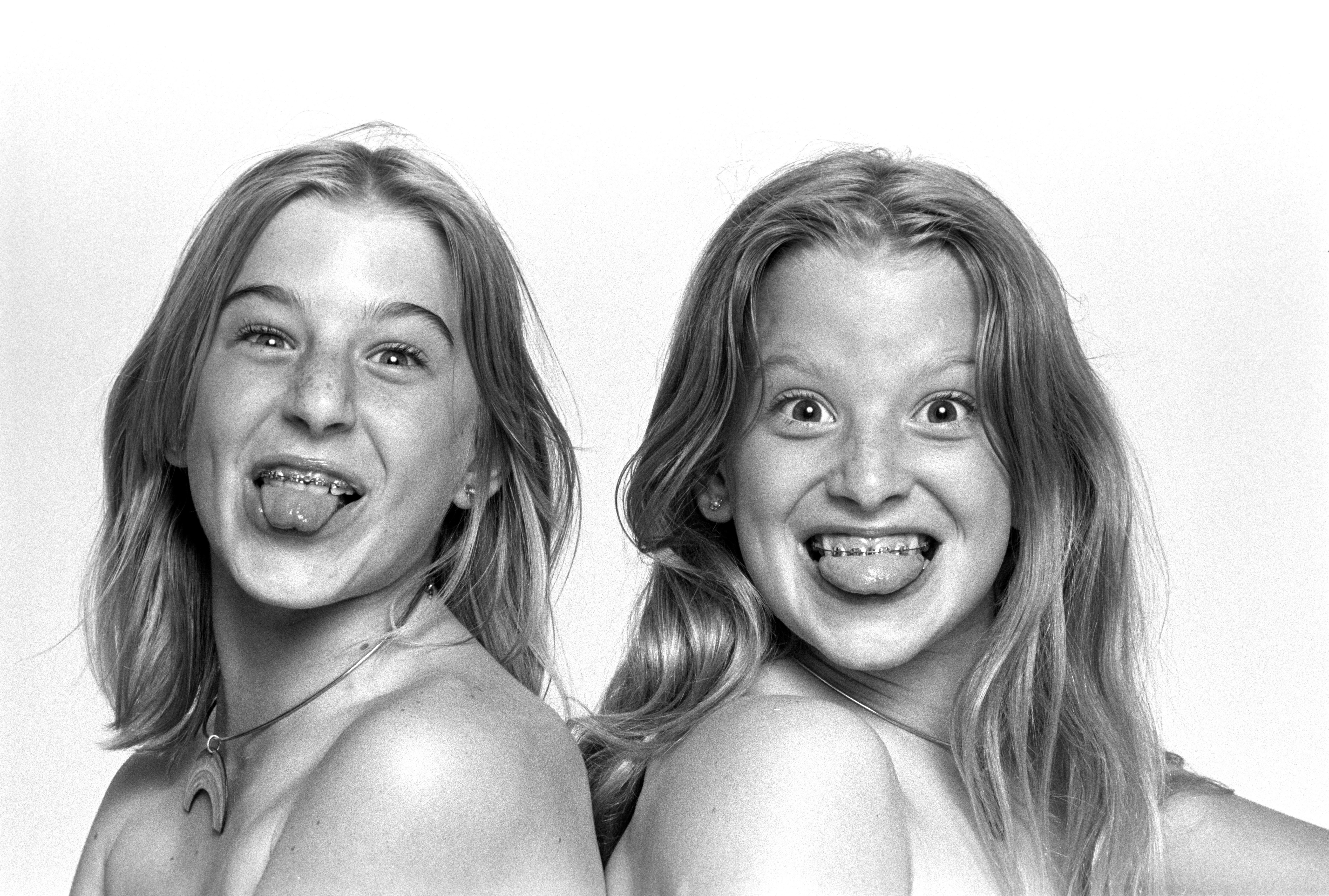

MoMu’s latest exhibition, GIRLS, explores girlhood through fashion, film, art and objects. To find out more about it, we spoke to its guest curator of film, Claire Marie Healy.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

Writer, editor, and curator Claire Marie Healy is telling me about Antwerp. Calling in from her office in London, she has just returned from a weekend there visiting the MoMu fashion museum, where a new exhibition focusing on girlhood has recently opened. Fittingly titled GIRLS, Claire guest curated the films of the show, alongside MoMu’s Elisa de Wyngaert.

Skilfully compiled, the exhibition is a multi-disciplinary exploration of what it means to grow up as a girl, tracing the ways in which girlhood has been worn, watched and experienced through fashion, objects, art and film.

Claire, somewhat of an expert on the topic, has written extensively about this in a regular column, Girlhood Studies, and was asked to contribute a series of essays to the exhibition catalogue as well as a montage film. “I think Elisa was interested to work with somebody who could bring in a perspective on coming of age moments in film related to girlhood,” she says. “I was really interested in bringing out the threads of that triangulation between film, fashion and visual culture”.

Alongside works by artists like Sofia Lai with her gnarled headless sculptures and photography from Eimear Lynch, who sensitively captures a teen disco in Ireland, there’s plenty of fashion from designers who have often felt at home exploring the visual codes of girlhood: communion-esque dresses by Simone Rocha, a teenage bedroom installation stuffed with Chopova Lowena skirts and Jenny Fax’s buoyant bubble shoes all play a role in centring the importance of girls in fashion and culture at large.

As you walk into another room, weaving between maximalist nail sets by Mei Kawajiri and a so-sweet-your-teeth-hurt archive of pink letters by Harley Weir, you’re likely to catch snatches of Rihanna’s Diamonds ricocheting around the room, casting a nostalgic glow on the pieces around you.

Follow the track into a dimmed corridor and you’ll find Girls in film – a montage of film scenes that explore the transitions and transformations of girlhood, beginning with a scene from Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film Marie Antoinette, showing the young archduchess getting dressed by members of the French court, ending with a snippet from Celine Sciamma’s Girlhood (2014) as a Parisian girl gang get ready before a night out, dancing to Rihanna’s 2012 hit.

Drawing on films as wide ranging as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and La Petite Vendeuse de Soleil (1999), Claire’s montage focusses on moments of dressing, undressing and accessorising in film, which for her not only “do a lot in service of the story, but also, give a sense of the girls’ inner lives.”

Hi Claire! What initially inspired your montage?

Coming of age as a genre is very wide in film, but my curation was [based] around how clothing and make-up exerts itself in [certain] stories and really brings out these moments of self-creation.

Was it difficult to narrow down your choice of films to include?

Because of my work with Girlhood Studies, I have a catalogue [of suitable films] in my head that has been built up over some years, so it was just about adjusting and supplementing those selections. Obviously, there are so many things that could have gone in there, but I think I just always went back to that north star of wanting to [create] a journey from uniformity to freedom, from restriction to self-expression.

Beginning with uniformity, films like Mädchen in Uniform and Picnic at Hanging Rock are set at a historical time when school uniforms were becoming more common, and that’s when audiences began to have a very set image of what a school girl in her uniform looks like. From there, you could eventually thread through to end up with self expression in the scene from Girlhood, where you see the girl gang [dancing to Diamonds] through the protagonist’s admiring gaze. It makes it a really special note to end the loop of the film on.

“Digging into a surface impression is what Sofia Coppola does very, very well”

Are there any aspects of girlhood that you feel are more pronounced compared to boyhood?

There’s always this push and pull for me. So with a scene from a film like Smooth Talk [1985], there’s a very innocent-seeming scene of girls getting ready in the mall. They’re displaying and dressing themselves and it’s also a rebellion against their parents. But, on top of that, they’re also very exposed to a male gaze – and one that can be threatening, which is explicitly what happens later in the movie.

So even when you have these moments of rebellion and customisation, it’s never just one thing. When you actually zone in on these moments in cinema, they’re very resonant to real girlhood – it’s the in-betweenness.

When you think back to 15-year-old Claire, how did she express herself through clothes?

I was really into indie and noise bands. But I would say specifically at like 15, there was this 1960s garage-rock band resurgence happening in Essex and we’d all go to see them. So it was a lot of Jane Birkin cosplay: long socks, shift dresses and Twiggy-style eyeliner under the eyes. I had the self-confidence to express myself through clothing and makeup but I was also extremely, extremely shy. I barely spoke. But I love those contradictions. That is the classic in-betweenness that the show is talking about.

Sofia Coppola features quite heavily in this exhibition. Why do you think she captures the spirit of GIRLS so well?

I think it would be easy to dismiss The Virgin Suicides’ popularity as something that’s about the girls being blonde, beautiful, the clothing and the era of the 1970s being nostalgic.

But through those surface aesthetics she’s actually constantly questioning, what does it mean for those girls and those characters to be seen by their surface alone? The boys [who narrate the film] are watching the girls, and there’s a sense of their entrapment within a patriarchal community and society.

Similarly, Marie Antoinette is all about entering into a state of being surveilled, being watched, and surface aesthetics being so pretty but the experience being such a trap. Digging into a surface impression is basically what Sofia does very, very well.

In one of your essays, you talk about “screencap culture”. Could you tell us more about that?

There’s this amazing film distributor and critic called Maya Cade and she talks about the way films are circulated online purely through stills with subtitles, and the online culture around that.

The reason I like the way Maya speaks about it is not only because she’s a very serious film scholar, but it’s also the way she acknowledges this as a mode of discovery for finding work that resonates with you, just like a cinema listing in a traditional cinema would be.

I like thinking about that, because it’s a way to give value to a process of research which is about emotional points of connection. And I think there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a teen girl-fuelled online culture. But the dismissal of the screen capture points to a wider culture where the emotions and knowledge sharing of girls are quite readily dismissed.