Kingsley Ifill is only now starting to understand

New exhibition Blue Roan is a trip down the rabbit hole of 15 years of meditative, painstaking work. It was worth it.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

Looking at artist Kingsley Ifill’s work feels like a flicker of a deep-seated memory; a sibling reminding you of something that happened on a long-forgotten family holiday, or the mental image of an ex as their name is mentioned in conversation.

Take Blue Roan (2015), a large screen print of a man at Appleby Horse Fair, wearing sunglasses, riding a horse through a body of water so deep it laps at his feet, soaking his shoes. Printed onto a piece of raw linen, the acrylic print crackles and drips around the edges; an analogue TV sputtering to life.

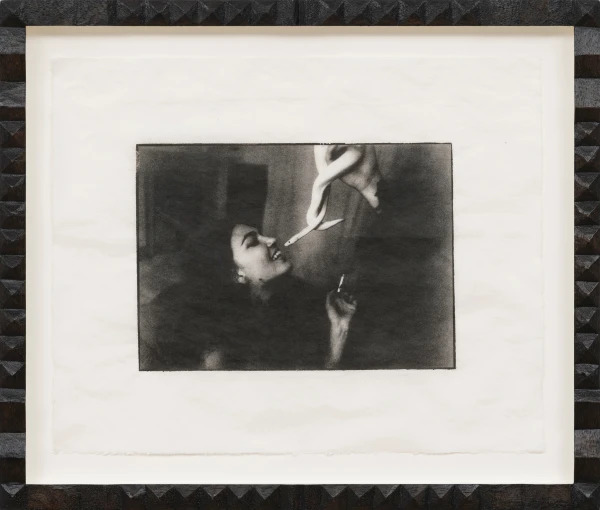

In another work, Lifer (2020 – 25), a woman beams affectionately at a small snake being held by a floating hand. As it pushes its head towards her teeth, she tilts her head back in the shadowy room while a cigarette in her left hand burns.

“Lifer was taken in 2012 and somehow this is the first time I’ve printed it properly,” Kingsley says. “I’d just got a Leica and was trying to learn how to use it. The photo was taken at some point when I stayed up all night with some friends.”

Born in Kent in 1988, Kingsley’s been fascinated by image-making for most of his life. “I had a paper round from age 12,” he says. “I’d stop off in an old people’s home that I delivered to and would flick through just to see the photos. Sometimes, if there’s a newspaper on the table in a café, I still do. I’m inspired by the frequency of which they’re published, as opposed to the precious approach of publishing art and photography books.”

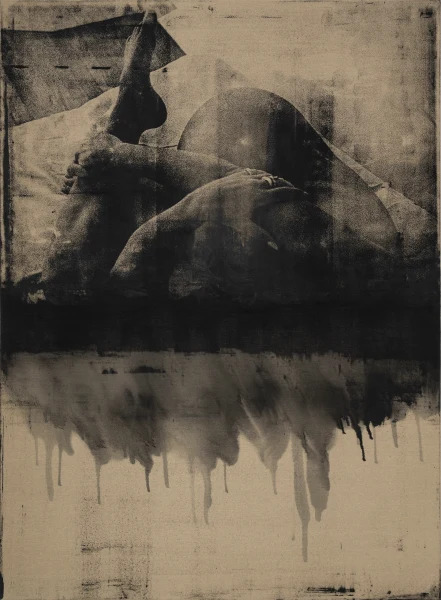

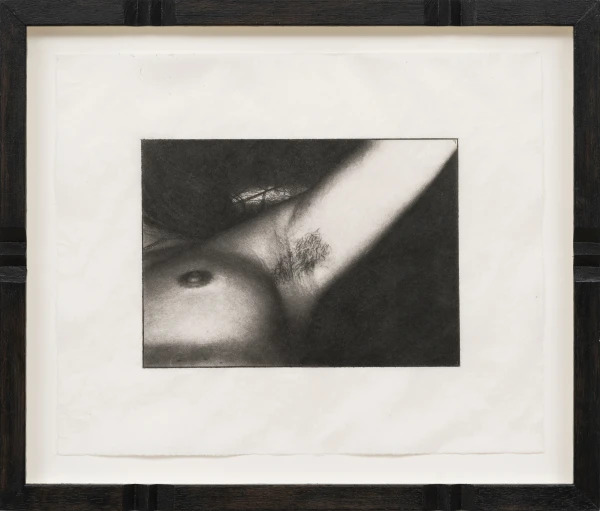

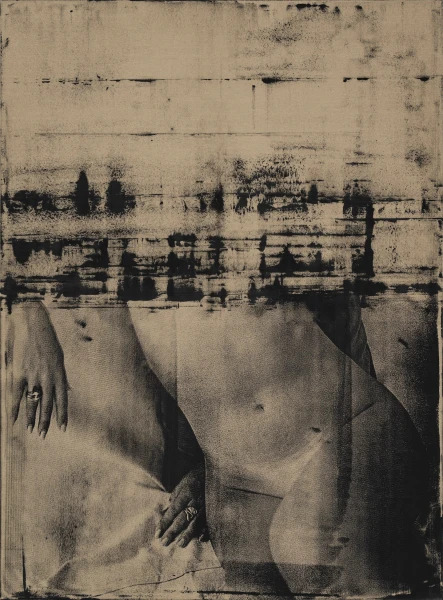

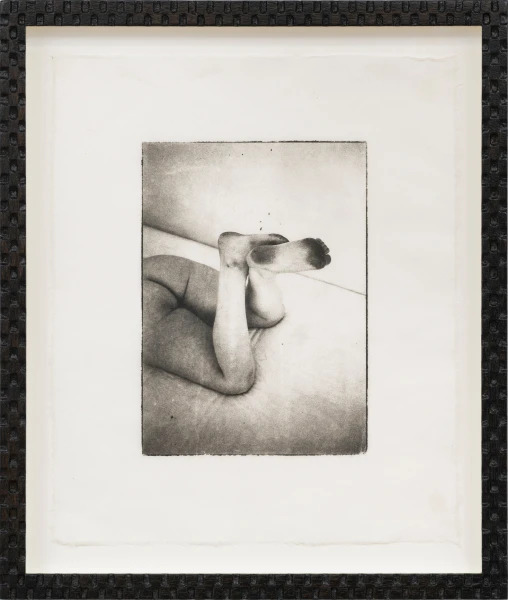

Now, a new exhibition at Hannah Barry Gallery in London takes a look at his practice so far, bringing together eight screen-printed paintings such Blue Roan, which gives the exhibition its name, and nine platinum palladium works printed on translucent Japanese washi paper – said to be the thinnest in the world at 0.02mm.

Selected from some 15 years of his multidisciplinary practice, the exhibition pulls viewers into Kingsley’s world of meditative, painstaking work. Each wooden frame is hand-carved by the artist while his prints are made using the platinum palladium method, a labour-intensive process that dates back to the 19th century.

Accompanying the exhibition is a short film directed by Felipe Narvaez. Shown exclusively here on THE FACE, it documents the artist at work in the run-up to the show. Like an Ifill come to life, the film features grainy, muted shots of Kingsley walking along a pebbled beach, creating large screen prints on his hands and knees and putting the final touches on his works.

“I’m always experimenting, it never really stops,” Kingsley says. “If I had five lifetimes, I probably still wouldn’t have enough time to see through everything. I feel like an amateur even though I’ve been refining some of these processes for 15 years or so – [it’s as if] I’m only now starting to understand.”

What have you been up to this week, Kingsley?

More of the same with a little in between. Spring has brought the sun, backyard, bare skin, feet up. Caught some trains. Stained my chopping board – pomegranate juice blood, almost black-red. In and out of the darkroom, as always.

Do you remember the first time you considered being a full-time artist?

I can remember getting my first real camera and consciously becoming aware of some kind of absorption into work. Feeling like I had to be on the lookout every waking second, as if there are now no days off. Realising images could fall from the sky at any moment, often when you least expect. I still feel that way.

Last year, you shot Skepta for our summer issue. Do you have any fond memories from the shoot?

Fondest memory is probably being in the garden and Skep mentioning his music festival Big Smoke. We spoke about all the different things people do at festivals, then he said he always goes to look for flowers to pick for his daughter. And that’s when we got the photo where he’s smelling flowers, which was probably my favourite photo of the series.

“The door”

Kingsley Ifill on his most prized studio possession

Where does the title of the show, Blue Roan, come from?

It’s Romany slang for somewhere in between. For example, if you are born of part gypsy blood and part non-gypsy, then you’re a “blue roan,” or if your dad has dark skin and your mum has light, you’re “blue roan” too. But the show isn’t about race.

I was thinking a lot about how the images and production within the work have been extracted from a variation of different times and places. It’s like a photo that becomes a new photo every time you blink. It may look similar, but it’s not the same and can persist, as if an extraction from the current time and place, into somewhere else.

Felipe’s film captures you a month or so before the show opens. Why did you decide to make it?

I’ve been friends with Felipe for a long time and 10 years ago he made a similar short film, shot in my studio. So we spoke about doing a follow-up. It just so happened to be while I was wrapping up the last pieces of work for my show at Hannah’s.

What’s the voiceover we hear in the beginning of the film?

It’s my girlfriend Dulcie reading fragments from randomly selected parts of a book by [Mexican poet] Octavio Paz that she found. We were in Kyoto, sitting in our hotel room with a window and balcony overlooking the river. I can remember us sitting on the floor; as she was reading it felt beautiful, and I had the feeling that I wanted to take a photo, but knowing that a photo wouldn’t record what I was hearing. Then I remembered there was an app on my phone which I never use. I opened it and pressed record, not knowing what would happen, but it worked out.

In the film, we see a phrase written on the studio wall that says “sympathy butters no bread.”Where does that come from?

I’m not sure. I moved into this studio in 2017 and it’s been written on the wall for as long as I can remember. I don’t remember writing it, but I wrote it. I was struggling for a long time. No doubt it was from one of these desperate periods, possibly a reminder to get to work, regardless of the situation and to keep pushing on.

What’s your relationship to your studio?

Sometimes I go there to sit, even when I don’t work. And sometimes I work, just to find some direction of what to work on. Recently, I was thinking of it as if the studio is like a film-processing tank. You go out and take photos, but then that film spends three, seven, 12 or however minutes in the tank, processing. Making the photos appear. Maybe art is just processing.

What’s your most prized studio possession?

The door.

Are there any key tenets or questions that you always return to?

Do I need the image, or does it need me? Would an image need an explanation, or can it be understood through sight and experience alone? My single belief is that, through work, the path leads to where I need to go, regardless of the twists and turns, or whatever feels right or wrong.

Blue Roan is at Hannah Barry Gallery in London until 17th May, would you believe.