The lore of Leigh Bowery

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session I Look 2 1988 © Fergus Greer. Courtesy of The Michael Hoppen Gallery

The fashion designer and lifelong outcast left Melbourne to become London’s most incendiary club kid. Thirty years after his death, his legacy is about to live loud and proud at Tate Modern.

Culture

Words: Joe Bobowicz

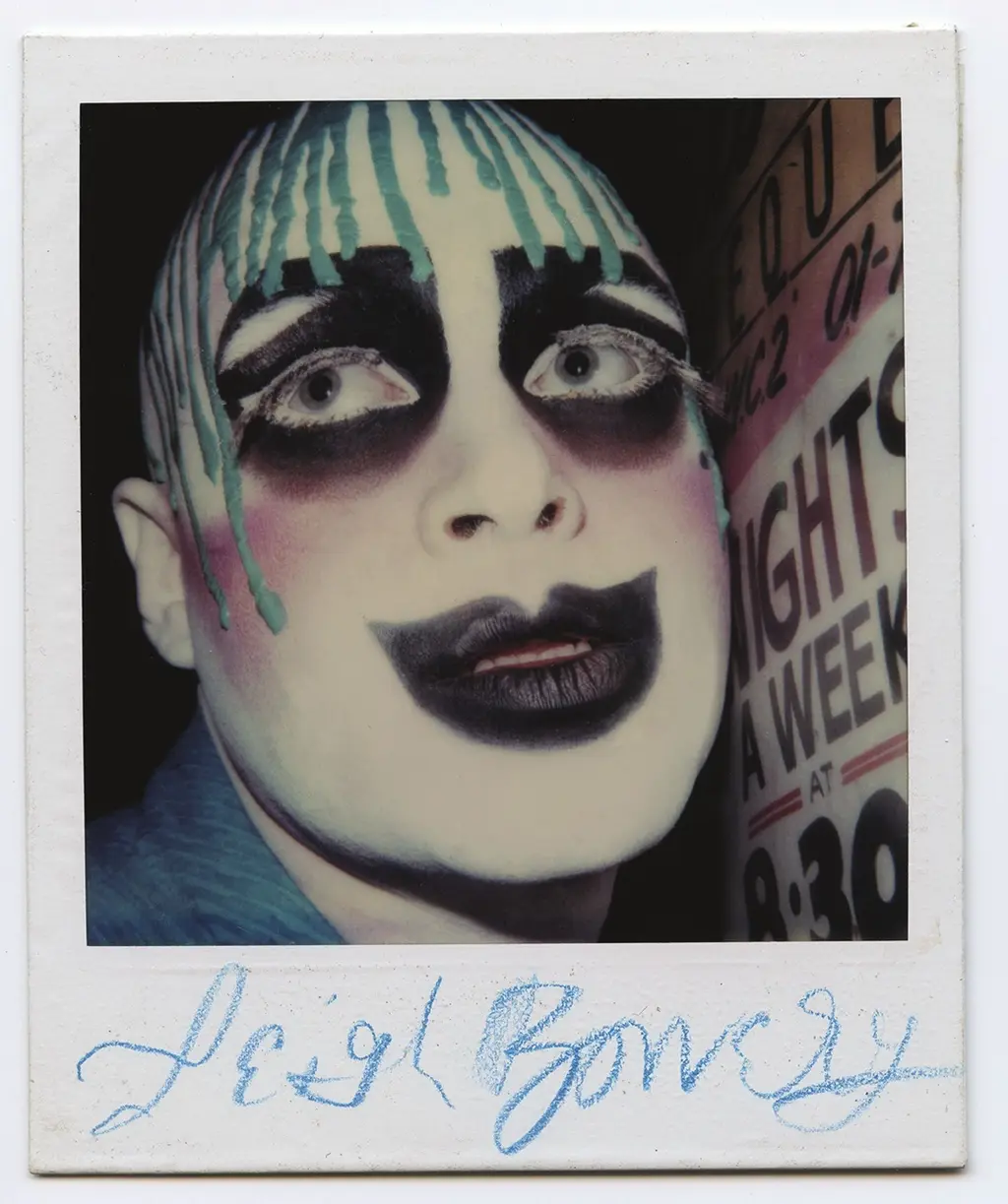

To talk of Leigh Bowery without mentioning his lore would be sacrilege. The fabled stories he amassed are as much a part of the Melbourne-born polymath as his kabuki slap or voluptuous sequin and satin dresses, embellishing the creative vision he shared.

Setting off for London in 1980 at the impressionable age of 19, Leigh left behind his family of Salvation Army Christians, inspired by the worlds of punk and new wave he’d come across in the pages of THE FACE and NME. Working in Burger King to fund his pipe dream, he quickly went from a timid wannabe finding his feet to the queen of the club kids, remaining a simultaneously welcoming yet intimidating figure on the scene.

To this day, you’ll be hard pressed to go through one fashion month without seeing a dozen references – accidental, proxied or explicit – to the fashion-designer-turned-club-host and performance artist. In fact, some of recent fashion history’s wildest moments were direct nods to the late, great Leigh.

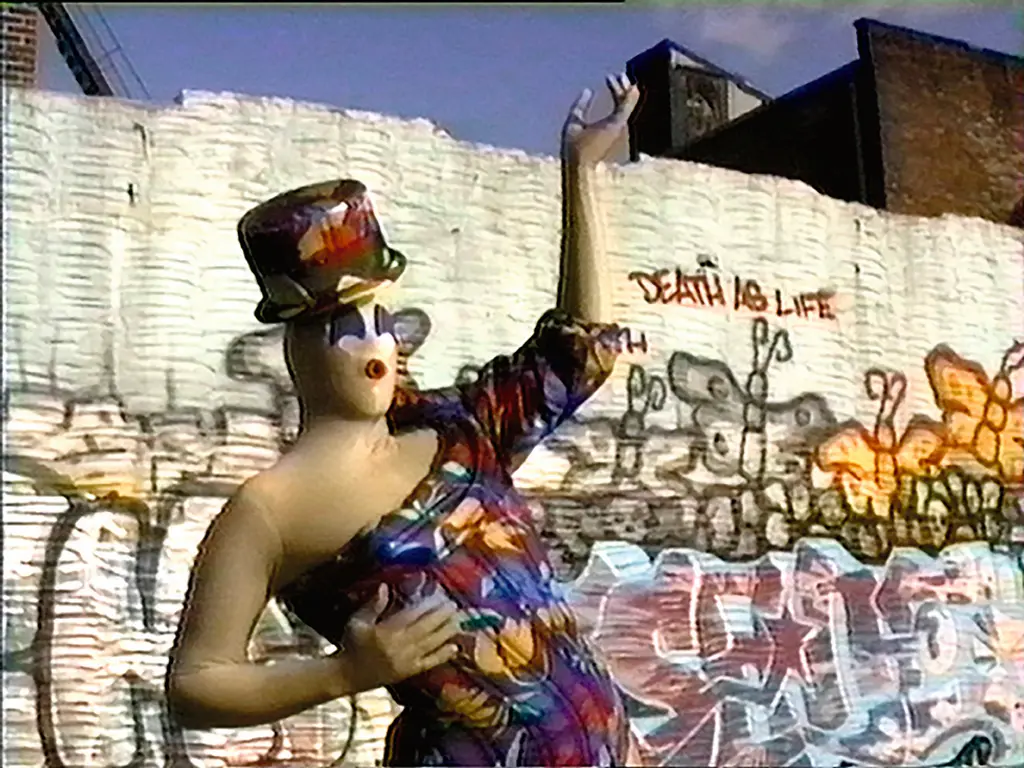

Charles Atlas Still from Mrs Peanut Visits New York 1999 c Charles Atlas Courtesy Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine New York 1

Polaroid portrait of Leigh Bowery 1986 © Peter Paul Hartnett /Camera Press

“His influence lives on in every look that dares to go a bit too far, that’s a bit too much – and that’s exactly the point”

Charles Jeffrey, designer

“I came across Leigh’s work when I was just starting out in London – initially through images in a library, then stories from people who were there,” says designer Charles Jeffrey, whose original Loverboy club night in Dalston, East London took inspiration from the wear-it, live-it philosophy of Leigh.

The world Leigh built with Taboo – his legendary, short-lived, 1985 – 86 nightclub in a Leicester Square basement – encouraged debauchery, gender-bending that only the kitschest couture scenesters or aspiring nobodies could fashion. That same blend of grotesquerie and opulence, both inviting and challenging – and, of course, larger than life – was a fil rouge in the looks punters pulled at the night Charles launched in 2014. In the decade since, it’s also been integral to the work he airs on the runaways.

“You see it in the makeup choices in Loverboy shows: the exaggerated features, the offbeat, almost chaotic play of colours and forms,” Charles says. “Leigh’s influence lives on in every look that dares to go a bit too far, that’s a bit too much. And that’s exactly the point.”

While Leigh toyed with capital‑F fashion, creating his own collections and modelling for others, he rubbed up against the commerce of industry, preferring instead to appeal to a small coterie of friends. Walking for the likes of BodyMap – Stevie Stewart and David Holah’s patchworked, big-pattern apparel – Leigh was a familiar guest at London Fashion Week, but he favoured launching his looks in night spots such as the Cha Cha Club and later Taboo. Leigh, then, was an underground hero, but he still broke through into the mainstream.

Charles Atlas Still from Because We Must 1989 c Charles Atlas Courtesy Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine New York

Charles Atlas Still from Because We Must 1989 c Charles Atlas Courtesy Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine New York

“It was quite apparent at the time that Leigh was striking out and making an impact in different creative scenes,” says DJ Princess Julia, who “fleetingly did coat-check at Taboo.

“It was after a while that Leigh’s interests expanded into performance, the art scene and music,” she adds, pinpointing his seminal (self-)installation at the Anthony d’Offay gallery in 1988, spearheaded by art dealer Lorcan O’Neill.

Taboo, though, was the ground zero for Leigh’s legend. The glitterati and actors quickly showed up. Soon enough Leigh had also ingratiated himself with the YBAs, even making a jacket for Damien Hirst. But not once did he sell out. The story goes that on Taboo’s dancefloor, Leigh once shimmied too near to Mick Jagger. “Fuck off, freak,” Mick reportedly growled. To which Leigh retorted: “Fuck off, fossil.”

The club was fiercely guarded by the original door bitch Mark Vaultier – a vicious queen who would present failed entrants with a mirror, asking that fateful question, “Would you let yourself in?” – and Gary Barnes, a lesser-known artist who went by “Trojan”. The latter was Leigh’s sidekick, unrequited love and a part-time rentboy – another ’80s demimonde star who, as reported in THE FACE’s obituary in 1987, had once tried to cut his own ear off. “Leigh, can you give me some help?” Trojan had apparently called from the loo of their shared council flat.

“We came from a generation whose only means of expression was how we presented ourselves to the world. Leigh took this to the furthest extreme”

Michael Clark, dancer and choreographer

Towards the end of his life, cut short by AIDS-related complications, Leigh would sit for Lucian Freud. “Leigh changed Lucian’s way of working,” says Sue Tilley, Leigh’s friend and biographer. “He made his paintings much larger, and made bigger brush strokes to emphasise Leigh’s flesh.” To Sue’s point, even without his platform heels, Leigh was a towering six-foot-two-or-three, and was the epitome of a big-boned beauty.

Leigh even founded his own art band, Minty, with wife Nicola Bateman and knitwear designer Richard Torry (they went on to tour with Pulp following Leigh’s death). So Leigh had range, to say the least, showcasing a toolkit of makeshift talents long before terms such as “world-building” and “cultural polymath” were being thrown around marketing suites. But this was much more than self-branding.

Leigh’s commitment to his world meant that he only ever appeared in outlandish, blue-faced get-ups, always affecting the most elaborate camp and speaking in soundbites that could have been pulled from the shopping pages of an ’80s Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar.

In one 1988 appearance on BBC’s The Clothes Show, Leigh minces around Harrods, afternoon tea in hand. “This is another one of my autumn predictions,” he says, curtseying in an appliqué dress and sheathed face. “It’s a beautiful garment, which has these rather strong satin flowers, swimming in a sea of sequins.”

Lucian Freud Nude with Leg Up Leigh Bowery 1992 c The Lucian Freud Archive All Rights Reserved 2024

Such performative speech, dress and mannerisms came together in one constant work of performance art. Michael Clark, a trained ballerina and modern dance choreographer, was drawn to Leigh, noticing him, Trojan and David Walls (“The Three Kings”, as they were known) at Jeremy Healy’s itinerant pop-up club Circus. Leigh was promptly commissioned to make costumes for a dance piece Michael was developing.

“It was based on the Echo and Narcissus myth,” says Michael now. “To me, Leigh and his two cohorts looked like ancient gods, in their platform shoes, crown-like hats, flowing gowns, and hot pants – all with more than a hint of Glam meets Picasso.” Entitled Flippin’ Eck! Oh thweet mythtery of life (1984), this was their first, most conventional collaboration, and was swiftly followed up by Morag’s Wedding (1984).

“Leigh had designed some hot pants for a female dancer, which had a landscape on the fabric and a large area of beige around her backside,” Michael continues. “As Leigh and I looked on from behind the stalls, I said to Leigh: ‘From here, it looks like her bare bottom is fully exposed.’ And that was the birth of the costumes for New Puritans [1984],” adds Michael referencing another famed, bottom-flashing production.

From there, Michael decided to set up his own eponymous dance company, free to bend the rules as he pleased and embracing Leigh’s wild ideas: dildos, bustles, platform boots and brown spots on yellow faces – a reference to Kaposi’s sarcoma, the soft tissue condition often afflicting AIDS victims.

Leigh eventually became an all-dancing member of the Michael Clark Company, using his body as a vessel for political and social messages.

“We came from a generation whose only means of expression was how we presented ourselves to the world,” reflects Michael. “Leigh took this to the furthest extreme.”

“The most recurring thing that came up in conversations was Leigh’s zest for life; the joy – and sometimes pain – that he brought to people’s lives.”

Fiontán Moran, curator of Leigh Bowery!

Part of Leigh’s power was the outrage he induced. Most notorious of all is his (literally) shitty 1990 performance in Brixton for an AIDS benefit. Loaded up with an enema, he bent over onstage, “accidentally” squirting the murky contents over the crowd. “I wasn’t there, but Leigh rang me the next day and told me all about it,” says Sue. “It caused a furore among all those present. But Leigh added fuel to the fire by writing a letter to the gay press complaining about the show, signing it ‘a disgruntled lesbian’.”

This sense of authorship and fabulation was integral to his lore. A compulsive liar and at times a tricky friend – he used to throw any of Sue’s belongings that he didn’t like out of her window – Leigh spoke fantasies into existence, meaning his friends and peers never quite knew what was real and what wasn’t. One thing is sure: there’s a whole, larger-than-life philosophy that Leigh left behind, which today’s generation can apply and carry forward in their own spaces, IRL or URL. The Tate Modern moment will offer a cohesive insight into that philosophy – “Dress as though your life depends on it, or don’t bother,” went Taboo’s dress code – writ large.

Baillie Walsh Still from Generations of Love music video 1990 c Baillie Walsh Courtesy Black Dog Films

Charles Atlas Still from Mrs Peanut Visits New York 1999 c Charles Atlas Courtesy Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine New York

“Central to it all has been Nicola, who has been a dream collaborator, allowing me to spend hours going through her archive, [sharing] many touching and hilarious memories of her time with Leigh,” says Fiontán. Anything of special note? “The most recurring thing that came up in all these conversations was Leigh’s zest for life; the joy – and sometimes pain – that he brought to their lives. And how uncompromising he was.”

To Fiontán’s point, Leigh’s world was so embellished and fantastical that even as his death loomed, he kept his HIV diagnosis secret, telling only Sue. The party line he gave her only added to a legend that reverberates through the decades: “Tell them I’ve gone to Papua New Guinea.”

Leigh died on New Year’s Eve, 1994, aged only 33. But the lore lives on. “I miss that man very much,” says Michael Clark.

Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London is at the Fashion and Textile Museum now. Leigh Bowery! opens at the Tate Modern in February