Pilgrimage to paradise: the agony and ecstasy of football fandom

© Martin Parr / Magnum courtesy OOF Gallery

A new exhibition from Martin Parr, Corbin Shaw and OOF magazine spotlights the footie fan. Who are ya?

Culture

Words: Felicity Martin

What does it mean to be a football supporter? Why do people travel from one end of the country to the other to watch their team – if they’re lucky – score a goal? What makes those few seconds of ecstasy worth the gamble? A new exhibition by football-meets-art magazine OOF explores the unconditional allure of the game to fans via the work of legendary British photographer Martin Parr and Sheffield-hailing multidisciplinary Corbin Shaw.

Martin Parr considers himself an accidental football photographer. He never set out to study the beautiful game as a subject, but over a 50-year career he’s been drawn to people enjoying their leisure time, which naturally took him to the terraces. In his typically hyperreal, documentary style, his shots put you in the centre of the game, getting candid close-ups of the fans. He doesn’t care for immaculate Premier League stars or even lower-level players: it’s the grimacing, elated, downtrodden supporters that interest him.

“I suppose I just like seeing people respond,” Parr says. “I’ve always liked watching people watching something else.”

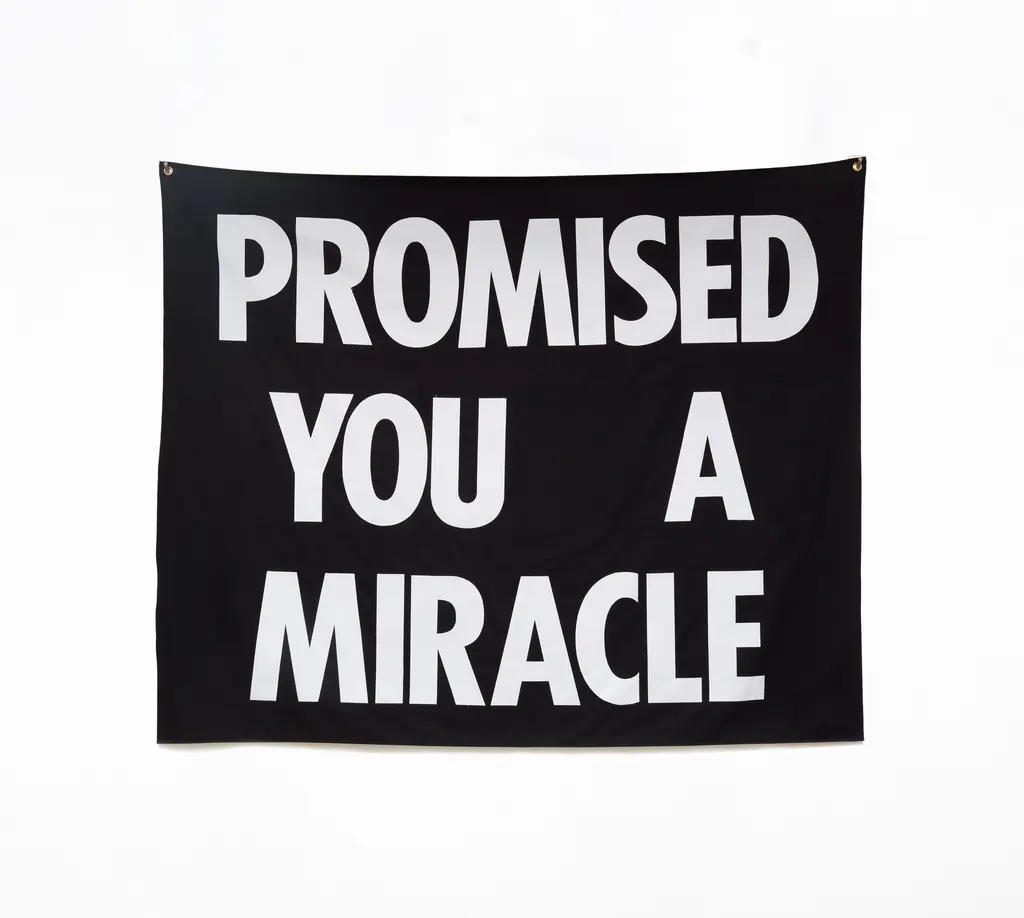

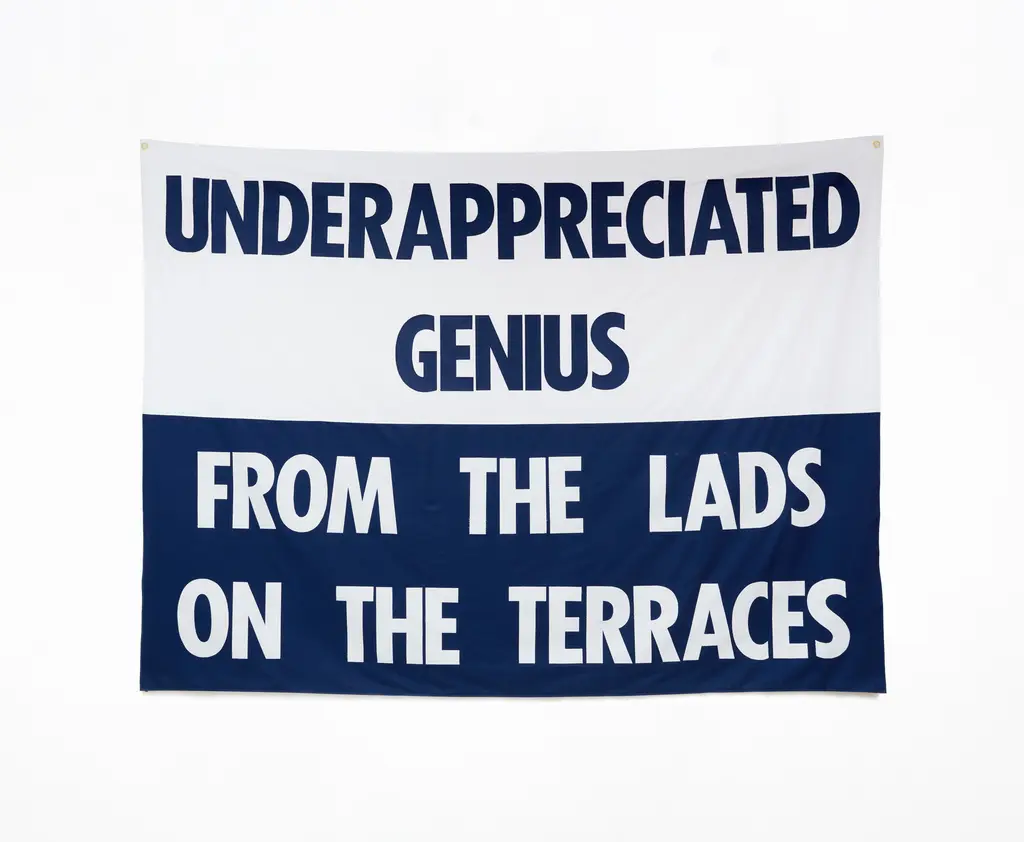

Shaw, who is 24 years-old, approaches football fandom from a different lens. His textile work explores its folkloric nature, how it permeates wider British culture, and subverts gender norms. With sewn-in phrases such as “Truly madly deeply” and “Dreaming of better days”, his fabric pieces reference pop culture and tradition while functioning like “messages of love,” he says. For the exhibition, he chose to make pennants: the long, tapering flags typically traded between captains of each team before a big match. Then there are football supporter flags, which are “usually talking about pride of place or hate for others in the city or a statement to the club. People view football as this two-sided fight, I like to think of it as a marriage between two teams or people.”

Speaking from his home in Bristol, where he can hear the roars of crowds at Bristol City games (although he’s traditionally a Man United fan from his college days), Parr hasn’t been able to visit the exhibition, which is located in a listed Georgian townhouse at Spurs’ stadium. He has myeloma, a form of blood cancer that has left him “slightly disabled,” he says. That hasn’t stopped him from shooting, snapping St. Ives from a mobility scooter last year. Euro 2020 fever papered over some of the fractures caused by covid, and it was something Parr found himself engrossed in while receiving chemotherapy in hospital. For him, it was a welcome distraction.

He remembers watching England win the 1966 World Cup, cheering along at home to black and white pixels on the television. The OOF exhibition contains a selection of Parr’s grayscale shots from the ’70s (he moved to colour in the ’80s). They are more sombre: trench-coated men stand gravely in single file in West Yorkshire, while Hartlepool FC supporters are dotted along a desolate concrete stadium. But the tribalism of football is shown best in full technicolour: fans adorn themselves in jerseys, scarves and facepaint as a stamp of their allegiance.

Martin Parr ‘Partick Thistle football fans, Glasgow, Scotland, 1995’, © Martin Parr /Magnum Photos courtesy of OOF Gallery

© Martin Parr /Magnum courtesy OOF Gallery

Shaw recalls first seeing Parr’s images when he was in year 10 studying photography.

“I remember when I first saw them that I actually didn’t like them, but the more I looked at them I was fascinated by how he’d look at all these small details that create the bigger picture of the British identity,” Shaw says. “The images create a clear visual of how football has changed so much over the past 50 years. Even I remember going to watch my club play when I was younger and the football pitch had huge holes in the mud and the ball would bobble, and the bloke who would walk up the stand and sell pies. You don’t get that no more. It was a real point in time and I feel like Parr’s images do capture that.”

Shaw went to his first match aged two, but the first season he really remembers is ’06/07 under Neil Warnock.

“It felt raw, unsanitised, perfectly imperfect,” he recalls. “I remember policing being different, I saw some right stuff kick off between fans. One thing I noticed when I moved to London, where I’ve been to a few matches at [Arsenal ground] the Emirates as opposed to [Sheffield United’s] Bramall Lane, is that the football ground serves the purpose of being another tourist attraction like the London Eye. When I watch my club back home it’s like being welcomed back into the family home. Everyone knows everyone. Oh, and the scran at football has gone down the pan. Get rid of them tough hotdogs! Long live the pie with chips and gravy.”

In today’s era of hyper-commercialised, ad-fuelled matches, Parr chooses to document the unglamorous moments that you don’t see on Sky Sports, but better represent the experience of fans. Creased Tesco bags are left on seats after a Wolves game, a man uses a pissoir by Old Trafford, and a sunburnt England fan enjoys the seaside in Essex.

“One thing that is evident from Parr’s images is that the spectator is an active participant in creating the spectacle of the football match,” Shaw says. “The crowd is just as important as the players on that pitch. The 12th man and all that – football without fans is nothing.” It’s a line that he humorously riffs on in the exhibition, with a blood red flag bearing the words: “Football without cans is nothing.”

Whether documenting dull match days or electric moments where a ball has just grazed the net, Parr practised positioning himself in the crowd, pinpointing an onlooker he wanted to shoot then wait for a big moment. “It’s more difficult these days to get into a Premier League match, but I did get in to see Wolves playing The Baggies [West Bromwich Albion],” he says. “There’s a guy – it’s the middle of winter, pretty cold, stripped down to his bare chest and celebrating very enthusiastically. Apparently he strips down every time a goal is scored. Everyone else is wrapped up but this guy doesn’t give a shit.”

The camaraderie and communality that football brings is central to Shaw’s work, which is rooted in the power and importance of terrace chants. He sees them as “one of the last remaining sources of an oral folk song tradition. My club sings Greasy Chip Butty before every single game. My dad taught me all the terrace chants through a CD he had in his car. It was almost like a hymn sheet. I’d practise the songs in the car then belt ‘em out at the match. The songs consisted of stories from past matches and hatred towards our local rivals, violence and love for our city and club.” He performed the song with his dad back when he was studying at Central Saint Martins. “I wanted to use it as a vehicle of how our masculine identity is taught like oral tradition. I’ve always been fascinated by the generational shift in my family of the men. For example: grandad – miner, dad – welder, me – artist. With my practice I’m constantly trying to unpack and unlearn what I’ve been taught and told that men should do, act, speak, wear.”

“I’m fascinated by these moments of expression from men who can’t speak [about] how they feel but can write it down on a wall or flag or sing it,” he continues. “I remember singing Can’t Help Falling in Love at the match with my dad. I’ve never heard my dad declare his love for anyone, only his football club, but his actions have always spoken a lot louder than his words. The idea for the phrases in this exhibition was to choose phrases that could be recontextualised. I wanted to choose phrases that wouldn’t look out of place in a football ground or on a bridge on the A57.”

For Parr, shooting on match day isn’t always plain sailing, he explains. People’s moods can shift so quickly in that moment that Parr – camera angled into the crowd – would often have to endure irritation as things took a turn.

“I shot an Aberdeen match quite recently,” he says. “I was photographing away, and they started to lose. It was against Rangers. People get more cross with you photographing them when they’re losing, as opposed to when they’re winning. I suppose, you know, people, when they’re winning their heads are in the clouds. You can get away with anything, but when they’re losing, they become more vulnerable. And they often say: ‘Don’t photograph me!’”

“I’m fascinated by these moments of expression from men who can’t speak [about] how they feel but can write it down on a wall or flag or sing it”

Corbin Shaw

As someone who’s been documenting our little island for half a decade, and has an admitted love-hate relationship with it, what does Parr make of the current state of affairs, with spiralling living costs, a corrupt government, and Brexit underway?

“It’s grim, really,” he says. “I mean, the climate crisis is being downgraded now, because we’ve all got to now be independent of Russia. So it means upping the North Sea, they’re going to start to excavate for oil and gas there. It feels like COP26 is a thing of the past, a historical thing, and it’s all sort of gone away,” he says. “It’s too depressing to even think about it, isn’t it! But you have to just go beyond that.”

While leisure pursuits might seem trivial in the face of this, you could argue they’re more important than ever.

“Football is an unrequited love,” says Shaw. “I know I can vouch for that, supporting a club like Sheffield United who’ve never won owt, but I’ll love them as long as I live. I almost feel like it’s my duty,” he laughs.

In the same vein of his decision to “focus on the love, devotion and hope that football brings us,” Parr’s work shows why documenting these small moments of joy, of community spirit, and of occasional heartbreak is so crucial.

“It’s a good distraction, isn’t it?” he smiles.

Martin Parr & Corbin Shaw runs until 8th May at OOF gallery, Warmington House, London – there’s more information here.