Stacy Kranitz is photographing life in rural Appalachia

In her new exhibition, As It Was Give(n) To Me, Stacy Kranitz subverts poverty porn in pursuit of a more accurate portrayal of working class communities.

Culture

Words: Jade Wickes

Photographer Stacy Kranitz has always had a deep fascination with Appalachia, the lush, mountainous region that stretches across 13 states in the eastern United States. The decline of its coal industry, which took hold in the mid 19th century, left the area and its people hugely impoverished; photographers duly descended on it in a bid to show the rest of the country what was happening there.

“They offered a simplistic and superficial image of poverty that has haunted the Appalachian people ever since,” Stacy explains. “I was drawn to making work there because I was interested in developing a project that would address the failure of objectivity in the documentary tradition. I wanted to look at a place where photography had failed the people it was trying to help.”

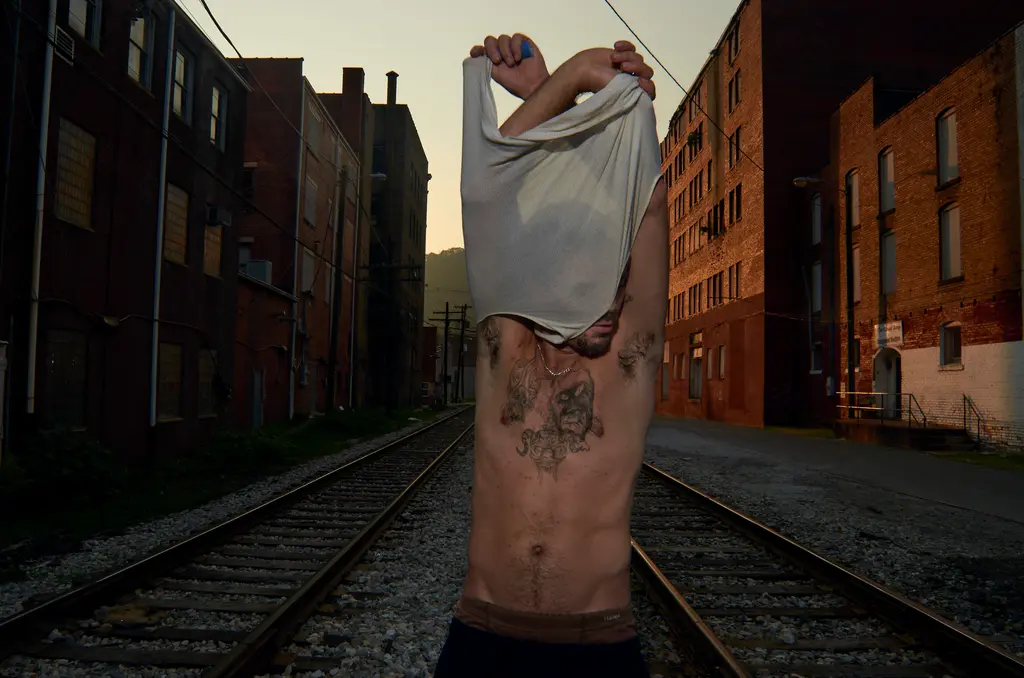

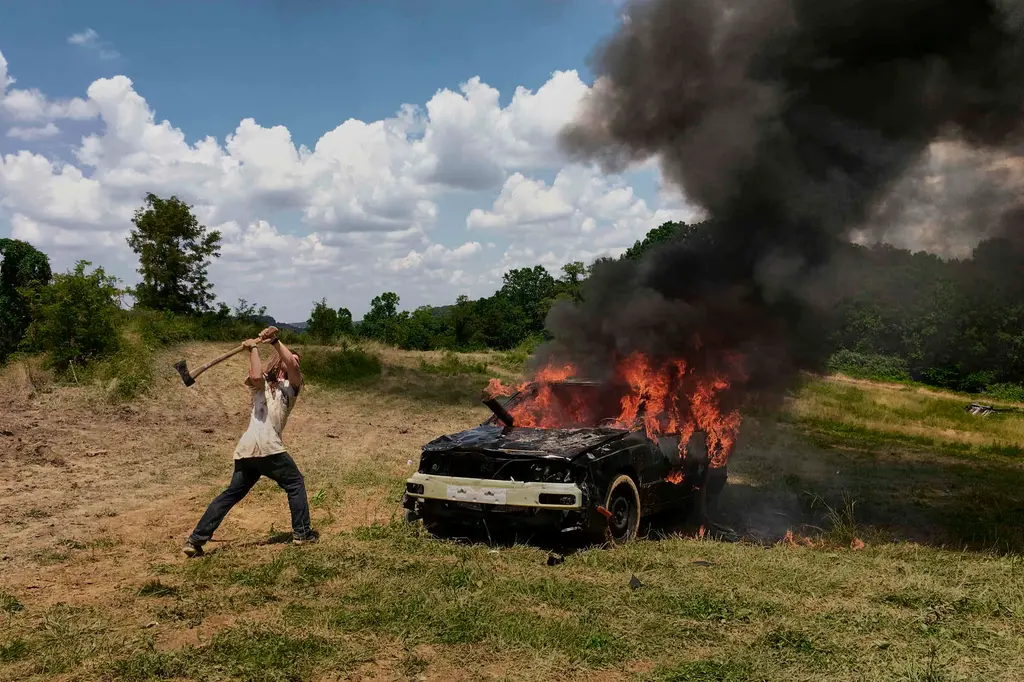

And so, all the time Stacy has spent in Appalachia over the last 15 years – she’s now based there, in the mountains of eastern Tennessee – has culminated in As It Was Give(n) To Me, an exhibition that pulls together photography, found imagery and sculptural artefacts that speak to the lives of marginalised communities. There are images of dramatic landscapes and burning cars, lovers embracing on horseback and girls stuffing menthol Marlboros down their bikini tops, each imbued with a melancholy that feels reminiscent of an Edward Hopper painting.

Since 2009, Stacy has observed plenty of changes in the region. “The most dramatic change was the downfall of the coal economy, but there was also the opioid epidemic, which wreaked havoc on communities,” she says. “There was a profound political transition at the end of Obama’s presidency, as Trump rose in popularity. The Black Lives Matter movement forced many people in the region to have overdue conversations about their relationship with the Confederate flag. The pandemic also illuminated the ways Appalachia’s rural healthcare system has been hollowed out and inadequately cares for people in the region.”

Catch As It Was Give(n) To Me at CCProjects gallery in New York, until 17th May – for a window into lives that are rarely documented for what they really are, and the friendships Stacy has built.

“[Those are] the most significant experiences from the many years I made this work,” she says. “I can’t imagine my life without them.”

Hi Stacy. What’s most important for you to capture about a person or a place when you’re taking a photograph?

I wouldn’t be interested in documentary photography if I knew the answer. I don’t believe that photographs have the power to be an authoritative view of a region. My work is careful not to illustrate a certain type of injustice in hopes of remedying it. I’m interested in the potential for photography to open up a new kind of narrative that examines our understanding of culture and place in a way that is poised between notions of right and wrong.

What inspires and influences you, generally?

It’s helpful to take a break from images and explore different approaches to storytelling. I read a book I cannot stop thinking about nearly a year ago, We Were Once a Family by Roxanna Asgarian. It got under my skin in a way no other story ever has. I have also gone down a deep rabbit hole during the last few years, obsessing over Barbara Loden’s film Wanda. It led me to a trilogy of books by Nathalie Léger that have had a considerable influence on me. And I always find myself returning to Cormac McCarthy’s eastern Tennessee novels. They reorient me when I feel lost.

The exhibition includes images from your ongoing series, From the Study on Post-Pubescent Manhood. Why have you chosen to show photographs from this series alongside As it Was Give(n) to Me?

It was just after the election of Donald Trump. My publisher Jack Woody was drawn to [the series] and how it signified a working-class rebellion that related to the rise of Trump. I found that provocative. Many of the people I met working on that series grew up with parents addicted to opioids. They found themselves stuck inside the orbit of their parents’ addiction, and I became interested in their collective disenfranchisement with American society, and a system of capitalism that has allowed pharmaceutical companies to descend on communities, addict them to substances, reap tremendous profit, and then not give a fuck about the ramifications.

The show’s been received really well. How does that make you feel?

It’s nice to share this work with an audience. I see photography as a triangle: a relationship between the subject, photographer and viewer. The exhibition is a vital part of that.

What do you hope people will take from going to it?

I hope the exhibition allows people to think about and question the many ways that documentary photography fails to represent a place.

Catch As It Was Give(n) To Me at CCProjects gallery in New York, until 18th May