What we can learn from Kate Moss’ 1993 living room?

© Corinne Day

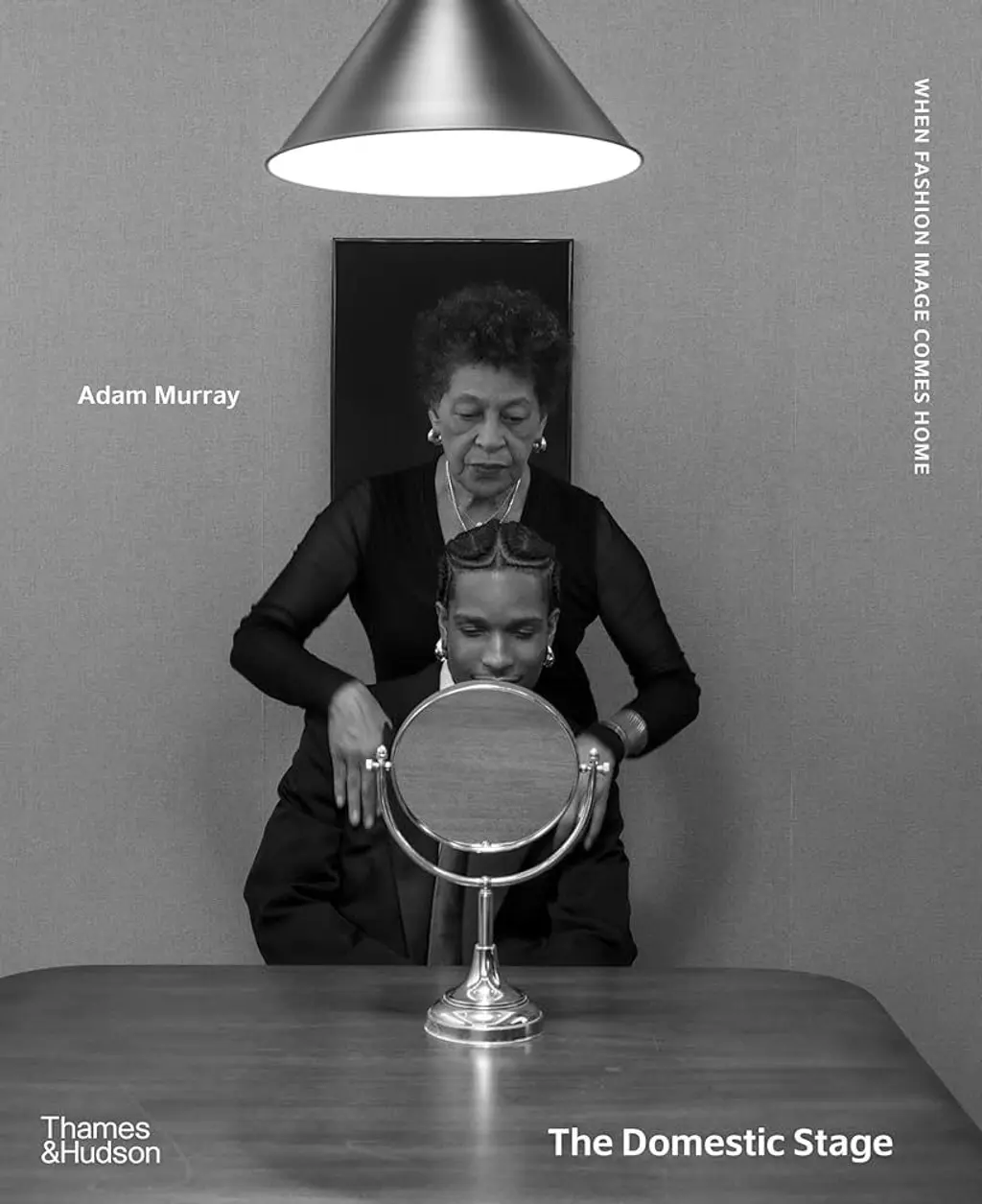

The Domestic Stage, a new book by researcher and Central Saint Martins lecturer Adam Murray, explores what happens when fashion photography steps inside your home.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

Adam Murray has always loved fashion photography. “THE FACE magazine was the first one I bought,” says the researcher and Central Saint Martins lecturer, calling in from his home in Derbyshire. “I remember being off school, sick one day and going to the newsagents to buy a copy with the Manic Street Preachers on the front cover.” That one was from September 1998.

For Adam, “actual magazines” hold so much more than their digitised, often fragmented – by way of social media – counterparts. “This project began with looking at print magazines,” he says. “They’re important because you see the context that everything is produced in.”

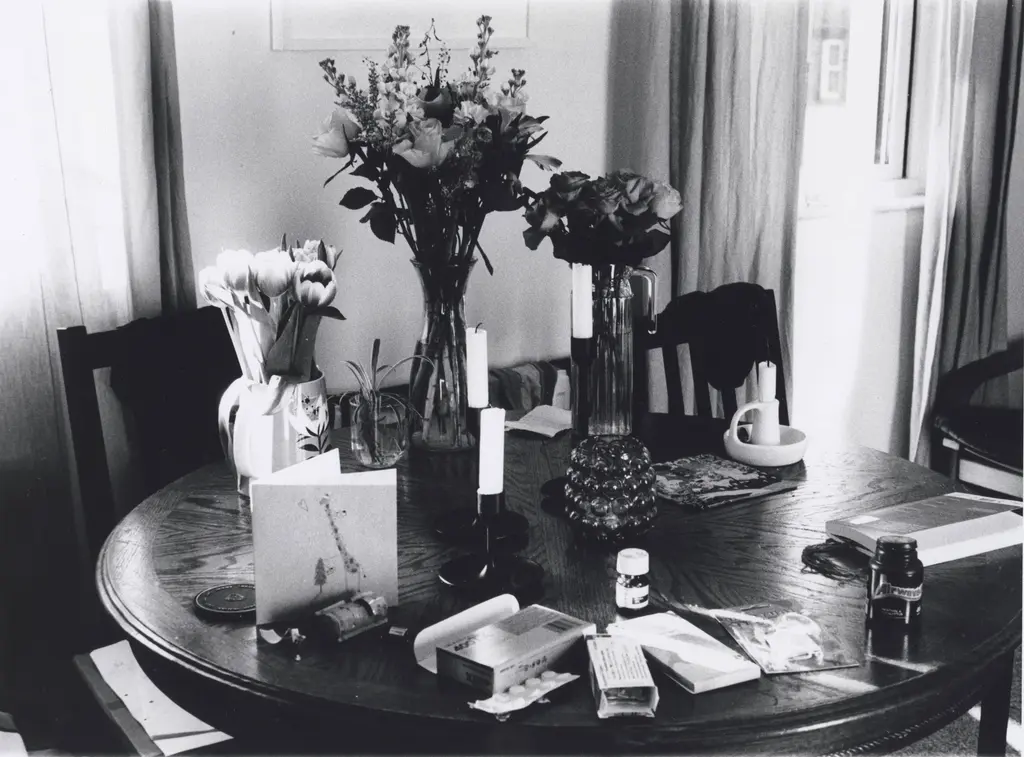

The project he’s referring to is his new book, The Domestic Stage: When Fashion Comes Home, which explores the history of fashion photography in home settings from the ’90s up until now. Think: Kate Moss shot in a draughty London flat by Corinne Day for Vogue in 1993, or A$AP Rocky’s shoot for Bottega Veneta last year, which saw the rapper sat at a kitchen table, photographed by legendary artist Carrie Mae Weems.

The latter shot is on the cover of The Domestic Stage. The image is a reference to Carrie’s Kitchen Table series from the ’90s, where the artist staged an intimate fictional drama in black and white – she sometimes played its smoking, laughing or sighing protagonist. Other times she was a partner, a mother, or a friend.

© Isabel MacCarthy

©Joyce NG

©Jesse Glazzard

©International Magic

Casting a spotlight on the kitchen table’s importance as a stage for so many of life’s dramas, the series’ influence has been profound and long-lasting. Though the Bottega reboot drew some criticism – arguing that the connection with a big brand watered down and commercialised the original reference – Carrie herself pointed towards the campaign as a fresh iteration of her previous work, dedicating the campaign to “fathers who dare to dream” and “fathers who dare to love” on Instagram.

“It felt like the perfect combination of a historical reference’s influence on a newer generation of people, [in tandem with] a contemporary work,” Adam says. “It summarised all the themes of the book in one story.”

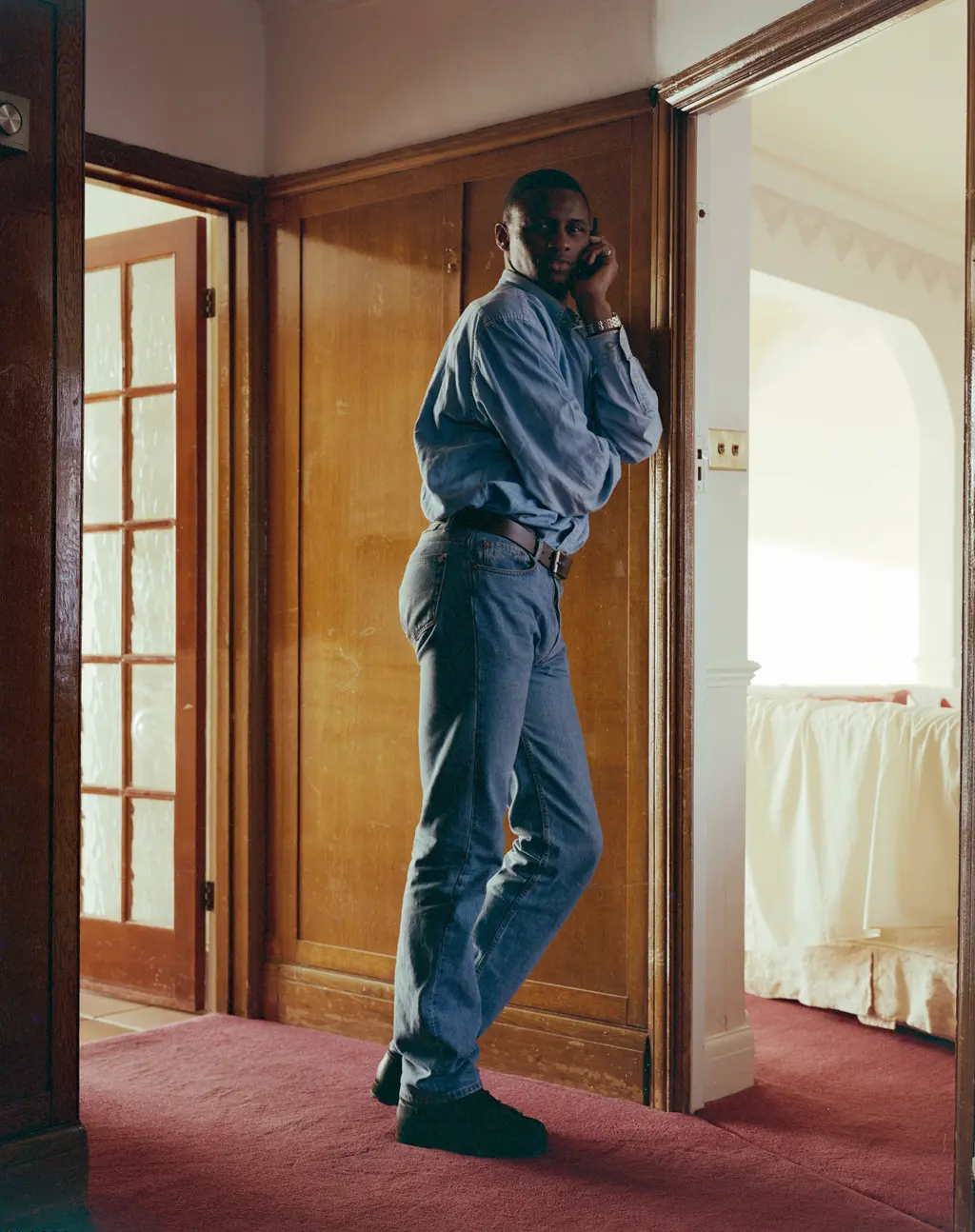

If fashion photography in domestic spaces sounds like a niche topic, Adam’s book makes it feel expansive and culturally important – which, if you consider all the legendary fashion shoots that have happened in living rooms and kitchens and dining rooms, it is.

Tracking the genre’s history, Adam highlights early shoots such as Tina Barney’s opulent family portraits of New England’s upper class in the late ’80s, bringing them into conversation with the likes of Steven Meisel’s 2007 Italian Vogue editorial Live On The Web, which featured grainy photos of models taking photos of themselves with webcams in unglamorous apartments.

“The history of fashion image has been identified as taking place in the street or the studio. The studio as this controlled environment to create these ideals, and then the street as the place where people either live out or reject these ideals”, Adam says. “Inevitably, this third space [of the home] is going to be relatively radical, because it goes against where any of this stuff should exist.”

©Moni Haworth

©Sahil Babbar

©Rachel Fleminger Hudson

©Nigel Shafran

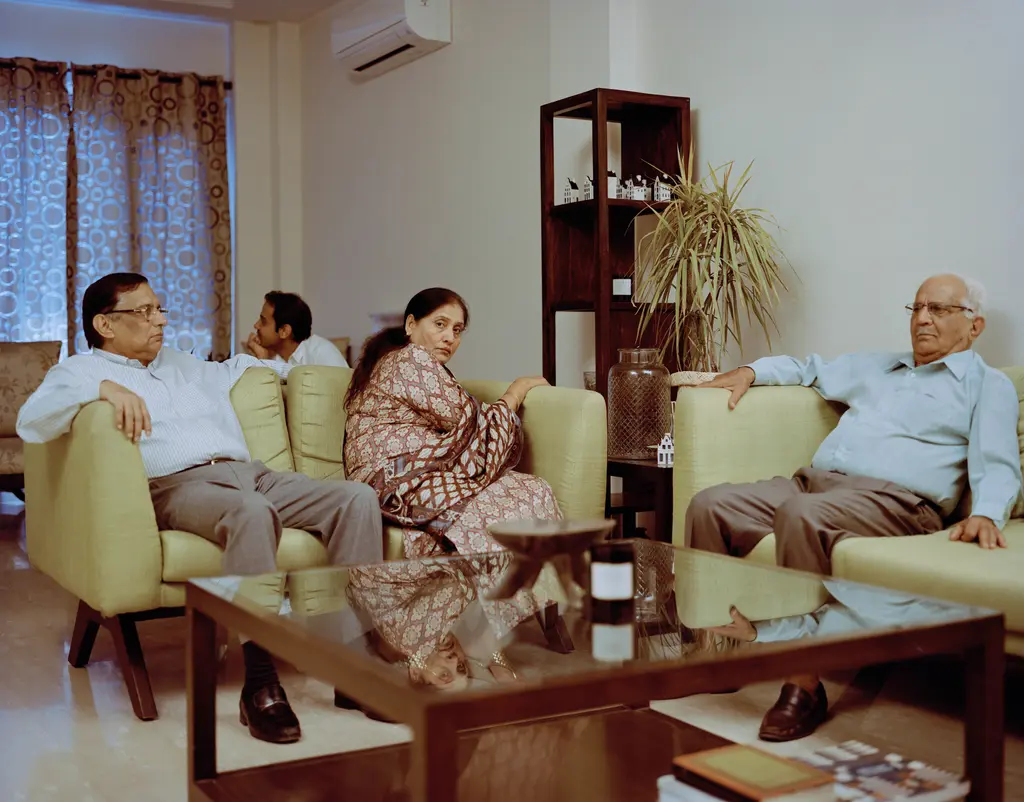

Alongside the aforementioned editorials, The Domestic Stage also explores our growing cultural fascination with the home more broadly. This first came to a head during the Cribs and Keeping Up With The Kardashians heyday, when celebrity homes transitioned from a private space to one that was ripe for public consumption. Since then, the place you live in has come to represent a space for mythmaking for some (just think of Dakota Johnson’s Architectural Digest video), while for others, it’s an intimate space where habit, restriction and comfort collide. Nowhere was the latter more obvious than during the pandemic, when our homes were both places of respite and sometimes suffocation. Jesse Glazzard, who features in the book, used that time to take portraits of his loved ones through FaceTime and Zoom, directing his friends through video calls and taking screenshots from home, in their homes.

Though Adam points out “there aren’t that many spaces where you can see genuinely interesting new fashion images being made anymore”, he cites a few exceptions: one of them being a 2024 FACE story that brought casting director Michele Mansoor, stylist Zara Mirkin and photographer Moni Haworth together for in Columbus, Ohio. Photographing young, local women at home, the deliberately lo-fi images show them wearing designer clothes, carrying toddlers, standing in basements and leaning against chain link fences, offering a compelling insight into the mundane.

It’s hard to imagine that FACE shoot taking place without Corinne in Kate’s peeling London flat back in 1993. Both shoots carry that same magic that’s made with such unassuming ingredients – normal girls, in normal homes captured for one of the first times in their lives in designer clothes, making fashion history.

For Adam, these types of new perspectives are made accessible through fashion photography in general. “It’s often dealt with as a frivolous, meaningless thing [compared to] its art or documentary [counterparts],” he says. “You’re constantly engaging with fashion in some way – beyond books and galleries. [I’m] arguing that it’s as important as all other types of photography.”