God Said Give ’Em Drum Machines and the sound of old Detroit

Top: Derrick May, Middle left: Blake Baxter, Middle centre: Kevin Saunderson, Middle right: Santonio Echols, Bottom left: Eddie Fowlkes, Bottom right: Juan Atkins

London Film Festival: techno gets the definitive documentary it deserves, in a brilliant portrait of the genre’s Black pioneers.

Music

Words: Craig McLean

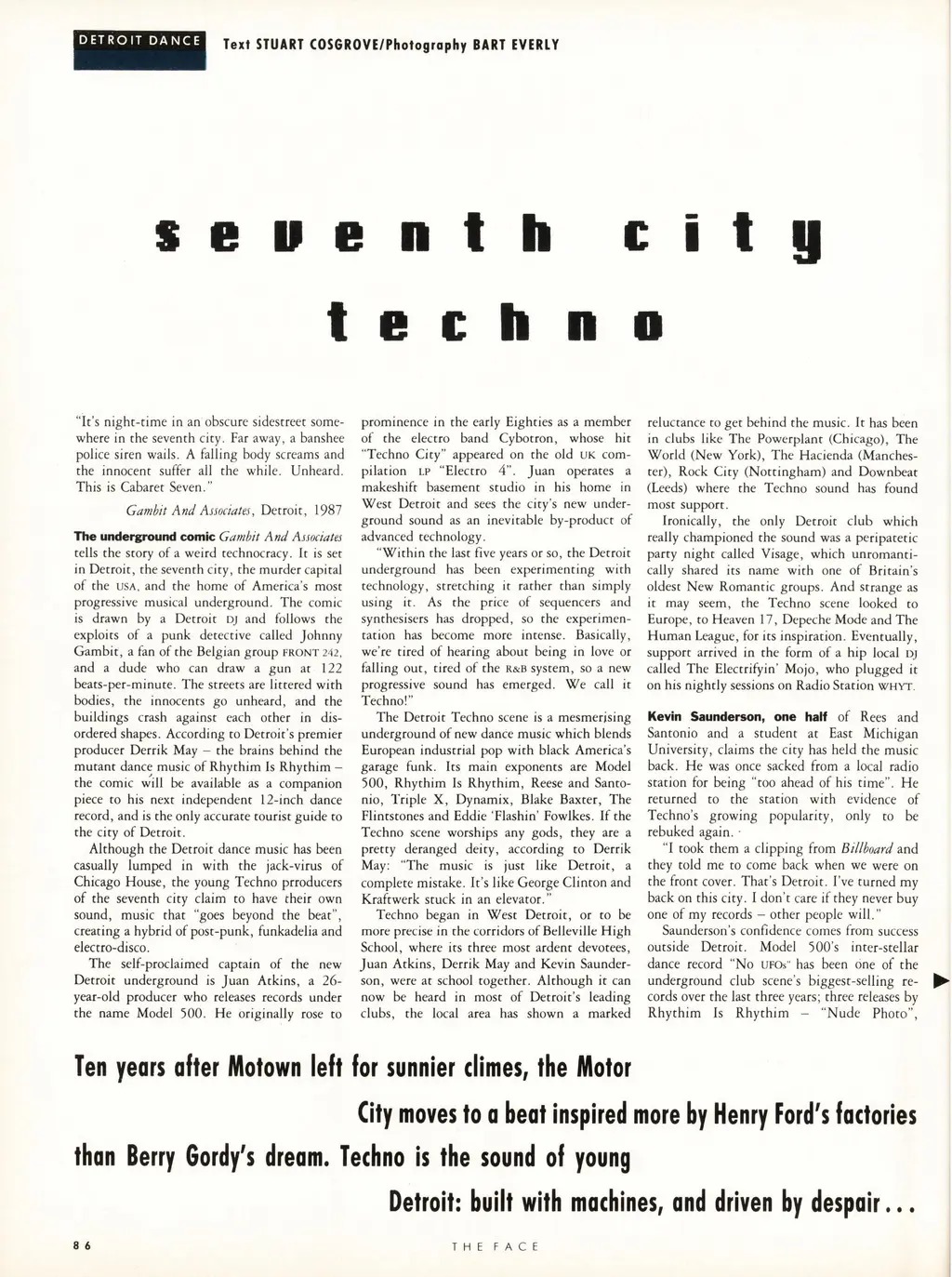

Kristian Hill sits in his studio in Detroit, brandishing the May 1988 edition of THE FACE. Electro-pop rocketwoman Yazz is on the cover, but the director has the magazine flapped open at page 86. “Seventh City Techno” runs the headline on a feature by writer Stuart Cosgrove and photographer Bart Everly.

“Ten years after Motown left for sunnier climes, the Motor City moves to a beat inspired more by Henry Ford’s factories than Berry Gordy’s dream,” runs the introduction. “Techno is the sound of young Detroit: built with machines, and driven by despair…”

“Yes, yes!” beams Hill. “This is the famous article about our guys!”

The director may be Detroit to his bones. But when he was researching God Said Give ’Em Drum Machines, his killer new documentary about techno’s Black origins in the city, the writings of Scotland-born Cosgrove (a mainstay of this magazine in the 1980s), “were important to do research for the film, [and] kind of how we were able to start looking for archive on these guys.

“Because there’s not a lot of video. Sure, there’s a lot of pictures. But there’s not a lot of information, or old archival stuff on Juan [Atkins], Derrick [May], Kevin [Saunderson], Blake [Baxter], Eddie [“Flashin’” Fowlkes], Santonio [Echols], the guys in the film.”

All that changes with 2022’s God Said Give ’Em Drum Machines.

FACE readers, dance music fans, even non-locals (“because people outside of Detroit knew way more about this music than many of the people in the city”) might assume everyone knows about techno’s founding fathers, and their roots in America’s seventh city. As a thrilling reminder, Hill and his team have shared with us their GSGEDM Essentials playlist of techno classics, here…

But like Hill knows better than most, that’s not the case everywhere you go. As Atkins – described in the film as the “inventor of techno… the spark plug, the pioneer in terms of showing the way” – tells the filmmaker’s camera: Black artists, these ground-zero adopters of the Roland TR-909 drum machine and Korg synthesiser, “got forgot or purposely whitewashed”.

This, says Hill, was the engine at the heart of his film, a labour of love that’s been 12 years in the making for someone who’s known many of the protagonists since childhood.

“The guiding mission was to tell a story about Detroit, about this music, in a way that people who had no idea about it could come away with [an understanding of it], and want to know more about it. There are so many people that know facets of the history,” Hill acknowledges, “[but] we couldn’t make a film for them. We had to make a film for people who have no idea about Detroit and its techno origins. And that’s generally the case: people here in the States have little to no idea about Detroit’s role in electronic music.”

To right that wrong, Hill has spent the best part of the last decade traversing the globe, shadowing, filming and interviewing techno’s progenitors and inheritors. He digs deep into the scene on the ground in Detroit, telling the stories of historic places and faces like reclusive Cybotron co-founder Rik Davis, a Vietnam veteran, and the influential late-night radio DJ known as The Electrifying Mojo.

But like the music itself, he also spans the world: travelling to Amsterdam with Juan Atkins, meeting Normski in London, interviewing Black Coffee in Johannesburg, probing British-Canadian legend Richie Hawtin.

Atkins, Hill says, was integral, because of his towering legacy, of course, but also because “I’ve known him the longest, since I was eight. Shit man, I had to interview Juan two or three times. The first interview was terrible… He was like, ‘you’re the little homie, you’re my guy from around the block!’ So early on he just… I don’t want to say placated me… But even in placating me, he knew to put me in real situations.”

THE FACE, May 1988

THE FACE, May 1988

THE FACE, May 1988

After a screening in New York of an early cut six or seven years ago, Atkins realised both the importance of Hill’s endeavour, and that he had to give a little more.

“After that screening, Juan was like: ‘Man, we got to do another interview.’ And in that interview, that’s the one where he has on the glasses, I was digging a little more with my questions. He gave me a lot more personality… and information. He reveals he’s very vulnerable.”

God Said Give ’Em Drum machines takes its title from a quote by the late DJ and Detroit groundbreaker Mike Huckaby, who died, aged 54, in April 2020. Interviewed by Hill, he describes a dream in which drum machines were to be the tools for local musicians to create a new future.

But the documentary bills itself in part as a tale of “mismanaged success”. What would Hill say is the best – that is, worst – example of that in the story of techno?

“I think one of the biggest mismanagements of their careers was hiding behind anonymity. Hiding their likeness, their names with these pseudonyms. Juan told me early on that he changed his name to Model 500 to hide his racial designation. That, in itself, is something that could, down the line, hinder you – in America, you got to put a face with the music.

“So that in itself was the dual-edged sword that these guys were walking. And it’s the difference between underground and above ground. This music is underground music, and the fact that you don’t put a face on it, then it’s even more underground.”

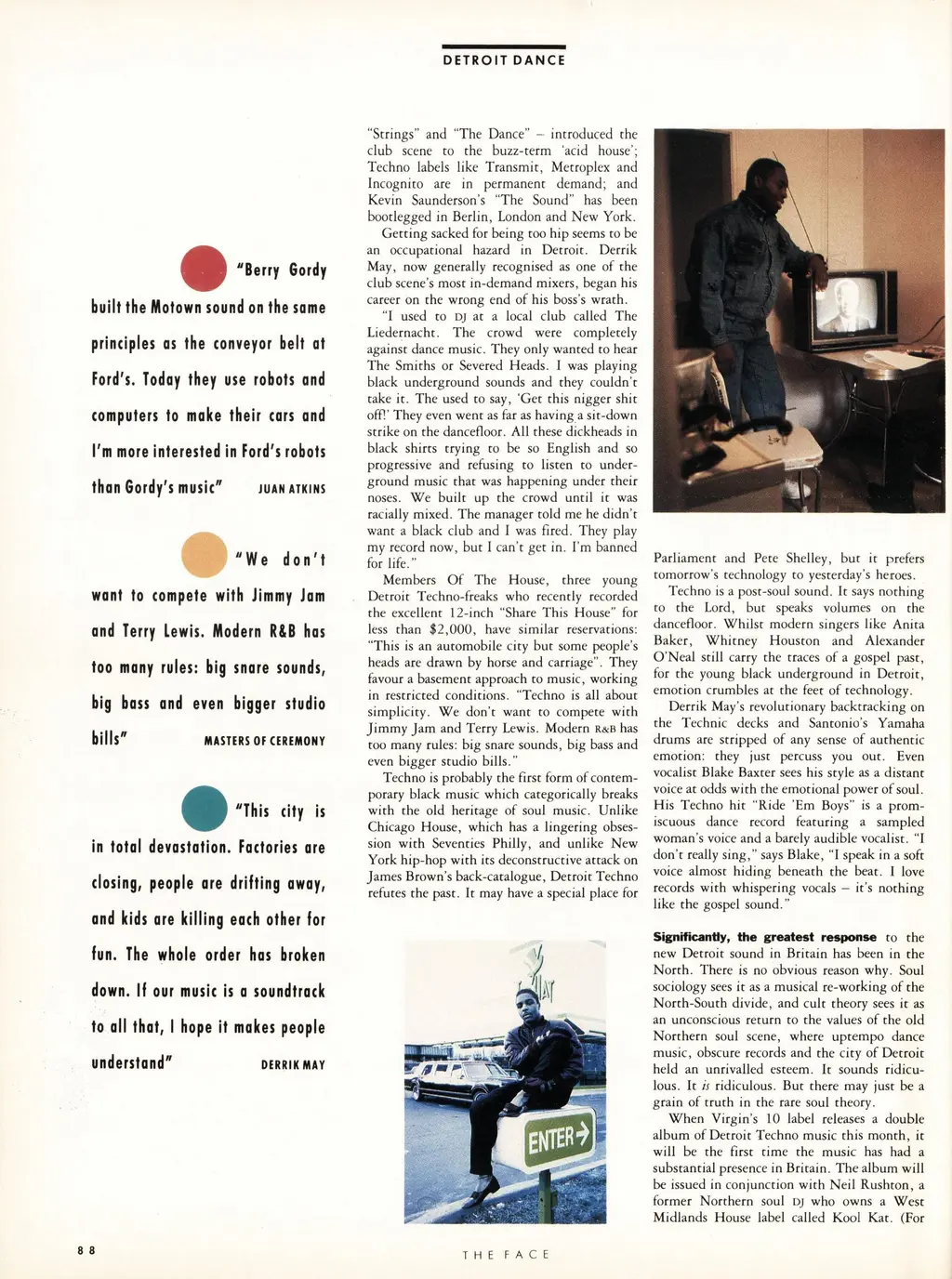

Norman “Normski” Anderson

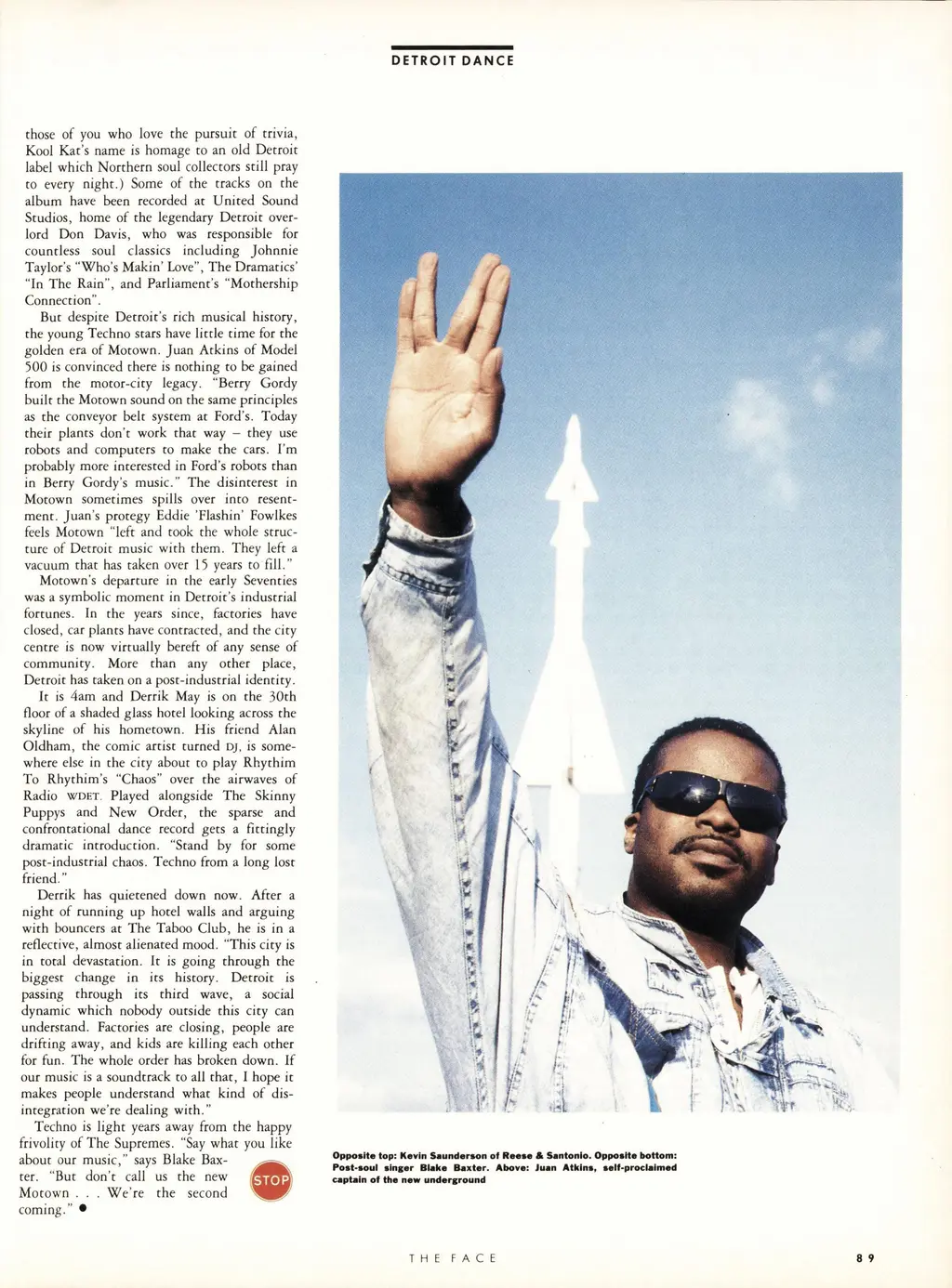

Kevin Saunderson

This, he thinks, reinforces an age-old issue for musicians: “Just the lack of understanding of the music business.” And of course, that impacts on the relationships of Hill’s original “guys”. As he puts it, “the Detroit dance music community is like a gang. And like in all gangs, it’s politics! Some of that,” he sums up, “is the reason why we don’t know who these guys are on some level.”

At its outset, the film pointedly foregrounds the gargantuan, Vegas-and festival-shaped success of those who ultimately benefited from Detroit’s techno pioneers’ innovations in DJing and electronic production. The EDM crew, the Calvins, Guettas and Skrillexes, became a brand, for better or worse the most highly-paid DJ-producers in the world, personalities and rock stars-slash-pop stars. Certainly the twentysomething Detroit musicians Stuart Cosgrove met in 1988 didn’t want any of that, and their music is a million times better for it. But, as God Said… shows, that came with a cost.

“An incredible cost,” agrees Hill. “Kevin had a producer discography he could lean on. Derrick had a couple records that he could lean on, but he had a DJ prowess that was universally unmatched. Juan has a legacy that people are still curious and interested in.

“But the other guys, they had to fight for their positions. Blake went off to be a success in Germany, in Berlin. Eddie held it down in Detroit, as well as fighting to be the fourth Belleville [guy].

“I don’t really lean into the whole Belleville Three thing,” he adds, referencing the sobriquet given to the holy trinity of techno dons (Atkins, May, Saunderson) who attended the same high school in the West Detroit suburb of Belleville. “Because that is also part of why we don’t know who these guys are. Where the fuck is Belleville? Even people in Detroit don’t even know where Belleville is!” To his mind, that’s even more pseudonymous.

God Said Give ’Em Drum Machines is a glorious thing, a true tribute to techno and the people who made it, and a corrective to a pop-culture history that, certainly in America, has overlooked the individuals who got the world dancing. But it’s a galling story, too: of racism, lost opportunities and the resulting tension between a star chamber of young electronic futurists in a beaten down city who, over three decades ago, created a sound that still throbs like tomorrow.

I ask Hill: at the end of his 12-year journey, is this film the tribute his guys deserve?

“Man, I hope so!” he answers, laughing and exhaling. “Throughout the editing process, you’re thinking about these guys because they’re alive, right? And their legacies are involved.

“Did I do a great job? I hope so. Did I make everybody happy? Nah, I didn’t make everybody happy. When you tell personal stories in the documentary space, it’s hard. It’s hard for people to see themselves as you see them. That was the toughest thing, being able to be fair to these guys in the edit bay. Because I know ’em, I love ’em, I got to see ’em again – even if we mad at each other!”

At the risk of causing further division, then: if push comes to shove, what are Kristian Hill’s all-time favourite techno tracks?

“Hmm, I have several!” Anything by Cybotron, or Time Space Transmat [by Model 500]… But then I really like to lean into the early Reese & Santonio stuff. Kaos (Juice Bar Mix) by Derrick and Blake Baxter. I love Blake’s early stuff, like Sexuality. But nothing is as transforming as Clear [by Cybotron]. You can play that anywhere, you know?”

God Said Give ’Em Drum Machines screens at LFF Thursday 6th October and Saturday 8th (twice). It’s also available to watch on BFI Player, 14th-23rd October. Ticket info