Don’t call KennyHoopla a rock star

Pop-punk is back and KennyHoopla is one of the new generation’s leading lights: a one-man band who left Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to follow a yellow brick road to Hollywood... then, um, back to Wisconsin again.

Music

Words: Lina Abascal

Photography: Daniel Regan

Taken from the new print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

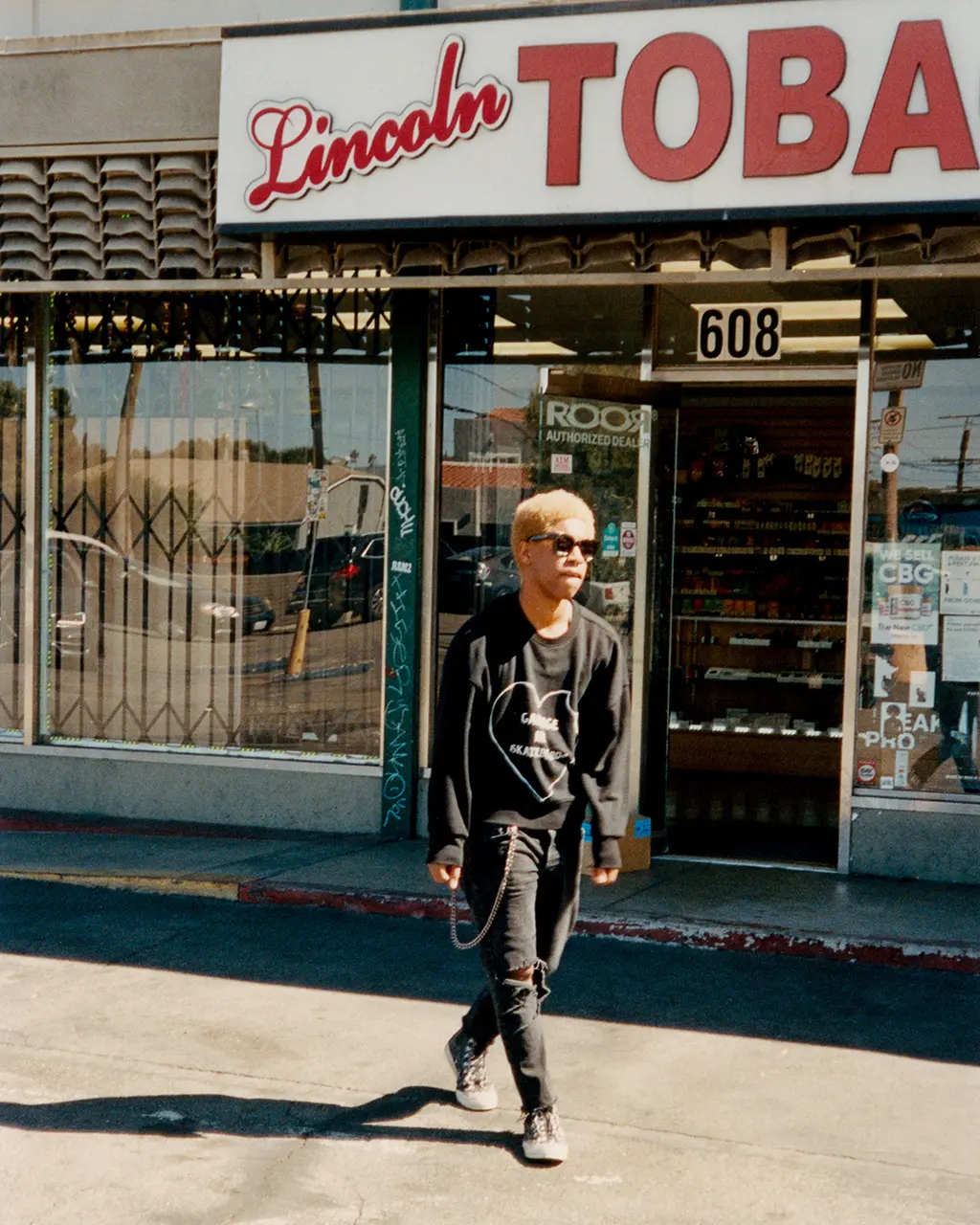

“OUR DRUMMER IS SICK!” KennyHoopla shouts from the stage of The Roxy. The 24-year-old stands clutching a microphone. His face is beaded with sweat. His hair is bleached and hanging out of his baggy denim jeans is a metal wallet chain. He’ll later rip the jeans after diving into the moshpit.

With its red neon sign a landmark on the Sunset Strip, The Roxy looks the same as the day it opened in 1973. There are other 500-capacity clubs in Los Angeles, but this place is something special, the kind of venue any rock-loving teen dreams of performing in, where The Ramones, Talking Heads, Prince and Patti Smith have all graced the stage.

No wonder Hoopla is psyched to be playing a sold-out show here – and another tomorrow night. The venue’s speakers are blaring the guitar, bass and drums of what sounds like a three or four-piece band. But Hoopla is just backed by a nameless laptop DJ – the drummer line was a joke. As he’ll tell me: “I have to make up for four people in the studio and when I perform. I have to make sure my music sounds like the chemistry of a really good four-piece band who have been best friends forever.”

Hoopla, born Kenneth La’ron, produces and sings (and sometimes screams) his songs, which span the rock gamut: from modern indie-dance-rock to pop-punk that sounds straight out of the Warped Tour 2006. The crowd is full of fans in platform shoes, plaid and leather who look old enough to know how to code a Myspace profile layout. But by the middle of the set, I can see multiple tattooed babyfaces in the VIP section – a telling symbol of the new era’s ambassadors.

First-generation pop-punk lovers might not be used to seeing artists perform without a live band, but the genre is being reborn and the rules aren’t just different, they no longer exist. KennyHoopla is one of its newest, most promising stars. But he still feels he’s got so much to prove.

Any fan of the genre knows that pop-punk is rooted in escapism. The top bands were from middle class American suburbs that inspire lyrics about running away to anywhere else. Mark Hoppus and Tom DeLonge formed blink-182 in Poway, California. Brand New and Taking Back Sunday were neighbours beefing on Long Island. Yellowcard and Mayday Parade are from hellhole central Florida.

“That’s probably the easiest part of it… all of these [pop-punk] tropes and clichés are real life for me,” Hoopla says when we speak on the phone the day after the show. “I live in a small town,” he says simply, a quiet overthinker offstage despite being a gripping extrovert on it. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Hoopla’s mother moved their family away from neighbourhood violence to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, when Hoopla was a child.

He didn’t have many friends and the few he had ended up not being the people he thought they were. Even if he was somewhere better, he felt alone and not at home.

From an early age, going solo, rather than with a band, was the only option that made sense for him. Maybe a lifetime of being his own best friend prepared Hoopla for the journey. He still doesn’t have many friends and admits a pang of envy over artists that have people on the sidelines cheering them on. When he started off making music, he wasn’t able to meet bandmates that understood his vision.

“I tried, but I couldn’t find people who I trust or people that are there [and] 100 per cent in it. It’s hard to find people who have given themselves fully to art and let themselves have the curse and blessing of it.”

Later, after he was first signed, he didn’t have the option to hire a backing band, a costly touring expense. But aside from a practical choice, not having a band is a statement about what he’s focused on.

“In a place where so much corny shit is happening and people are trying to be rock stars and shit, the most fuck-you thing I can do is not have a band, and just meet the audience and the world face-to-face, and let that do the talking.”

As a teenager, Hoopla began by posting one-off rap songs with rock-inspired production on SoundCloud. He self-released Beneath the Willow Tree// in 2016, a lo-fi EP filled with 808-laced beats, vocals drowned in vocoder effects and drone‑y songs without choruses. After signing to Sony Music subsidiary Arista Records in late 2018, he moved to Hollywood. He only lasted three months.

The experience spawned his appropriately-titled single hollywood sucks//, the best song digging at LA since Death Cab for Cutie’s Why You’d Want to Live Here. The track is breakneck fast and in-your-face. At The Roxy, it ignites a moshpit. Hoopla nails the status-obsessed, smooth-brained culture the city is known for with his lyrics: “Hollywood sucks/Can you please move your Prius/You are not fucking Jesus/He hates LA”.

Some fans might have thought he was kidding when he sang “Hollywood sucks, I’m moving to Wisconsin”, but he wasn’t. Quickly burnt out, Hoopla did move back to Oshkosh, the opposite of the pop-punk make-it-out-of-here story. “How bad is Hollywood if you have to move to Wisconsin? Pretty bad,” he laughs.

“I don’t belong anywhere. I’m trapped spiritually, and somewhat physically, in my surroundings. It’s kind of second nature,” Hoopla continues, letting out a laugh that’s followed by a sigh.

But that restless feeling is what drives him to create. He found life in lockdown pleasingly productive. Not touring, not focusing on doing “any clown shit” on Instagram. Just making music was his ideal way to fill the time. His dreams started to come true. But it soon felt like it was happening too fast.

The results of a year spent inside were net-positive, but there’s an endearing scepticism that saves Hoopla from ever sounding too much like a “rock star”. In May 2020 he released the EP how will i rest in peace if i’m buried by a highway?//, which featured a breakout title track that takes inspiration from indie-dance outfits he loves, such as Two Door Cinema Club and Bloc Party.

Just over a year later, he dropped Survivors Guilt: The Mixtape//, a collaboration with his childhood hero, blink-182 drummer Travis Barker.

He also had a lot of time to engage with the media, including appearing on the covers of Alternative Press and Kerrang!, developing his profile to a point he believes has made his name bigger than his “artistic growth”.

Trying to coordinate this interview and secure tickets to his show, I see what he means. Our email chains have a mix of management, label people, day-to-day-managers and publicists.

When we speak he has other interviews afterwards, back-to-back. Two days after his Roxy shows, he warms up for Machine Gun Kelly at the 5,000-capacity Greek Theatre, before embarking on a full US tour with the headliner. Next year, Hoopla has a three month tour across the US and UK.

Nonetheless, he insists that, “I feel like I haven’t done enough yet. Like, technically. But I’m in these positions.”

Whether he believes he deserves them or not, the opportunities keep coming. Everyone around Hoopla seems to be treating him like part of the major label Pop Punk 2.0 Machine. As those armies of attendant publicists, managers and industry figures attest, there is a wave to be ridden, something of which Hoopla is only too aware. “People are hopping on trends and it sells,” he says with a shrug.

Pop-punk is in a drastically different place now than it was in the ’90s and ’00s. Skipping years of rehearsing in parents’ garages, smelly van slogs and noon slots on the Warped Tour, artists now have a shot at going from zero to mainstream in a flash. Broadly speaking, this is partly due to the accelerated pace of streaming-era music. Specifically in the case of Hoopla, it’s also partly thanks to the enhanced celebrity profiles of his collaborator Barker and tourmate Kelly, which in turn has arisen from their PDA marathons with, respectively, Kourtney Kardashian and Megan Fox.

“There hasn’t been something light in so long, specifically in rock music. If we’re going to bring rock music back, we need to take it to square one, which is lightheartedness”

KENNYHOOPLA

Nothing – including Pete Wentz and Ashlee Simpson’s relationship – has ever put the scene at the forefront of pop culture the way it is now. Kim Kardashian West may have kissed Wentz in the video for Fall Out Boy’s 2007 single Thnks Fr Th Mmrs, but even that was months before Keeping Up… first aired. In 2021, when Kim said her daughter North West loves Hot Topic, the clothes store of choice for generation pop-punk, the scene’s alternative credentials felt like a distant memory.

But the new gen didn’t appear out of nowhere. Throwback club nights like Emo Nite do tours around the US playing nostalgic favourites off a laptop. All Time Low and Paramore songs are soundtracking TikToks. From around 2017, rappers like Lil Uzi Vert and the late Juice Wrld brought emo-influenced rap to the radio, while the king of SoundCloud rap himself, the late Lil Peep, rapped over beats that sampled Brand New and Underoath. We have been primed and pumped for guitars, checkered Vans and tartan everything – even at the cost of our feeds swarming with tongue-kissing selfies from millionaire couples.

But Hoopla’s love for Barker is based on a shared passion for pop-punk, rather than his celebrity status.

“I thank God for people like Travis,” he says. “He’s really about it and truly loves music, and he’ll just sit there with me all night. He is obsessive over it the way that I am.” That said, Hoopla still feels obliged to earn a few more stripes. “My favourite bands made shit in a garage, they didn’t go to a big producer. I’m just trying to establish myself as an artist to make sure that I am good enough before I think about doing features.”

In the past, Hoopla has said that he dislikes interviews, which might be one reason why he’s not the most forthcoming conversationalist. But now he seems to understand the role they play. During our talk he’s grateful, thankful and overly apologetic for answers he worries are “not right”.

He’s doing his job, even though it seems he’d rather let his music speak for itself. Compared to its earlier wave, there’s been a degree of progress in terms of diversity in pop-punk, with Willow Smith adopting the sound on her 2021 album Lately I Feel Everything and Meet Me @ The Altar – a trio of female musicians of colour – taking the scene by storm. But KennyHoopla is still a Black artist in an overwhelmingly white genre, and he’s felt himself being tokenised and pigeonholed. During the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, he noticed an inauthentic influx of attention from both corporate America and new listeners (he was part of the inaugural #YouTubeBlackVoices artist class of 2021). Every day he was being added to playlists of Black artists, which made him feel awkward.

As lockdown restrictions have loosened and he’s been able to meet fans and the industry face-to-face, the feeling of being othered has only increased.

“I’ve been feeling segregation between white and Black artists in pop culture,” Hoopla says. Whether it’s backstage at festivals or people coming up to him after shows, he’s experienced discrimination because of his race. “People are hating on me, it’s very blatant, it’s weird,” he tells me, choosing not to elaborate. “It doesn’t feel good.” On his first single from his SoundCloud days, 2017’s down-tempo lost cause//, Hoopla warns in the chorus: “And If I die young/I was born with a target on my head”. He knows there’s pressure from the social and political climate to make something serious.

But when writing the songs on Survivors Guilt – an album he calls a mixtape because it is a “conjunction of ideas” – Hoopla stayed true to the classic themes of pop-punk. “There hasn’t been something light in so long, specifically in rock music,” he says. “If we’re going to bring rock music back, we need to take it to square one, which is lightheartedness. People wanted more of my voice and it’s my generation’s time in life to be loud.”

Hoopla’s music stems from “an actual place of adversity” and he promises we’ll hear more of that on future releases. “I haven’t even tapped into my life, the things that I’ve been through and that I want to connect with people through.

“Not that I want to be a rock star,” he adds. “But a true rock star, someone that I would want to see at the forefront of music, is someone that is a hero. A hero is someone who only gets strong off of their losses and doesn’t make that their story. Their story is who they saved, and what they saved, and how they did it. I want to be a strong person and I want to be a strong artist.”

“I want to be a person full of love. In this industry it’s so easy to feel like I am doing this performance. I am only trying to grow as Kenny, not as an artist”

KENNYHOOPLA

On more than five occasions during our conversation, Hoopla touches on the topic of whether or not he is a rock star, constantly reminding me that he really doesn’t want to be one, or be considered as one. No matter the industry’s agenda, his number one focus is continuing to grow and be himself, even at the odds of sounding corny.

“I want to be a person full of love. In this industry it’s so easy to feel like I am doing this performance. I am only trying to grow as Kenny, not as an artist. When you try to grow as yourself, that complements you as an artist. I’m not trying to be anything. I’m always going to be Kenny… I think that is what we need. I think that is a rock star.”

Still, make no mistake: as much doubt as KennyHoopla expresses in our conversation, it’s not down to a lack of belief in himself. Rather, it’s a result of his tendency to get existential and analyse everything.

“To truly believe in yourself fully is a risk,” he concludes as he mentally prepares for the work that’s to come. “It feels like you’re looking down from a cliff edge and you’re like: ‘I’m gonna jump but I don’t know what’s down there.’”

At The Roxy, for his encore, Hoopla performs hollywood sucks// for the second time to a fervent crowd who are singing every syllable of every word. The first time he sang it, he stepped into the moshpit. This time, he catapults himself up and straight into the arms of his fans, turning a swan-dive into a stage-dive. At this moment, in mid-air, KennyHoopla has no fear of what he’s jumping into.