Original Farm Boys: documenting the rise of the UK’s most hyped drill crew

A new photography zine captures the Tottenham rappers’ summer block party.

In 1976, less than ten years after Broadwater Farm’s construction began, the government wanted the Tottenham estate demolished. A regeneration project was scrapped in the early ’80s due to lack of funding, and in 1985 the area’s notorious reputation was cemented by riots that attracted national press. But these days, fans of UK drill music recognise residency on The Farm as a badge of pride, largely thanks to OFB.

The collective (who’s moniker stands for “Original Farms Boys”) have been mentored by Headie One, who’s arguably the UK drill scene’s biggest crossover success. A couple of years ago, OFB’s YouTube numbers began to surge as they became the most hyped act of UK drill’s second wave, and last year they transitioned from underground hype to an industry-backed touring act.

Their Tim Westwood Cribs Session quickly hit the two million views mark – becoming the most-watched episode of the street rap cypher series of all time – and The Guardian published a lengthy feature on them afterwards. They supported Headie One across the UK and headlined their biggest gig to date at London’s Scala venue. It’s hard to count the exact number of OFB affiliates, but the core duo is based of Double Lz and Bandokay (the son of the late Mark Duggan, another famous Farm resident). Another member, SJ, was also central to the movement, and he appears prominently on their 2019 mixtape Front Street as well as the artwork. In May 2019, SJ was arrested for murder, and he’s currently serving a life sentence.

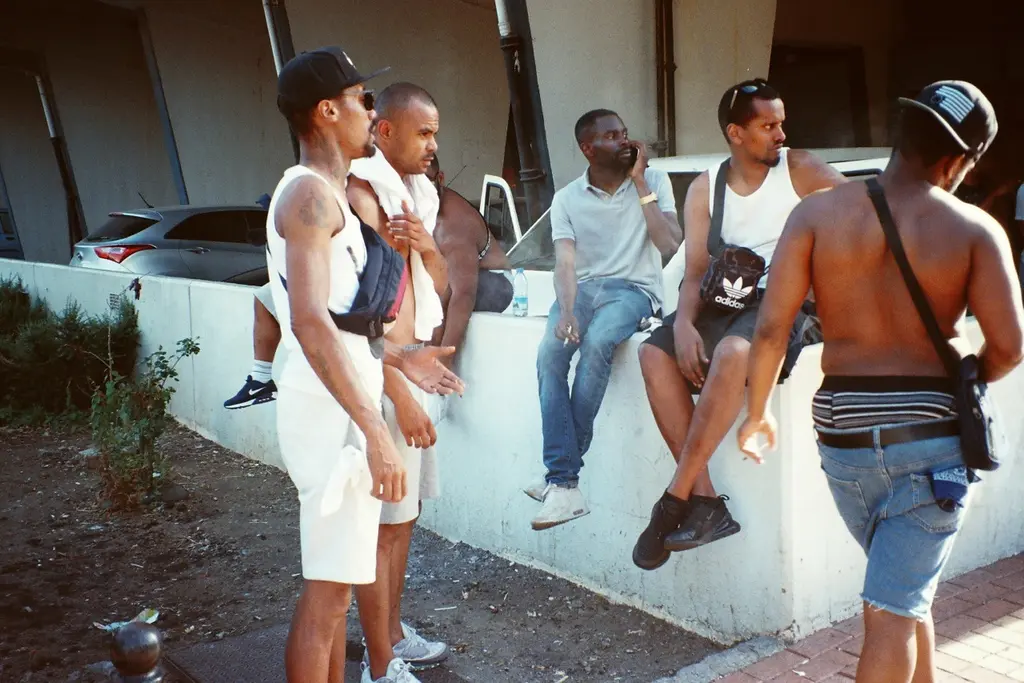

Jack Murray is an artist who’s been involved in various projects on Broadwater Farm. His new limited edition zine Front Street comprises of the photographs he took of OFB and the Broadwater Farm community around the summer of 2019. The zine costs a tenner, and all proceeds go to the Tottenham Food Bank. Check out some of the images and read about Murray’s perspective below.

What led you to shooting OFB around Broadwater Farm?

Over the years I’ve been creatively involved with projects and campaigns on the estate, so I became familiar with the place and some of the people. In early 2019 we began talking about what I could contribute to the OFB movement, and this is one of the outcomes.

Can you tell us a bit about the area?

The estate’s in Tottenham, north London and was built in the late ‘60s. The area has one of the largest black communities in the country, so naturally the estate reflects that, but it’s a very multicultural place. You’ve got people of Irish, Turkish, Albanian and Colombian heritage living there amongst a long list of other backgrounds.

The buildings themselves were inspired by the French architect Le Corbusier. You can see them from miles away in every other direction but at the same time it’s tucked away within the heart of Tottenham, away from the high road. The blocks are iconic in my opinion, and should be maintained properly and listed in the same way Trellick Tower or the Barbican has. The history of The Farm and its social relevance – both positive and negative – is too important to be bulldozed by property developers.

OFB have risen to be one of the most hyped acts in UK drill. Why do you think this is?

I’ve only been on the farm sporadically over the years, but I think the success of OFB was always on the cards. Their lineage, the place they’re from and their age has best positioned them to push the UK drill scene forward. The genre is still in its infancy but OFB are part of the first wave of people who have grown up with it, so their flow and delivery is up there [with the best].

In recent years, the mainstream press has been preoccupied with the negative side of UK drill music. What are the positive aspects of it that you saw?

Most of the photos in this zine are from the OFB block party last summer. Seeing hundreds of teenagers (majority girls) flocking to the Farm from all around to catch a glimpse of OFB, take selfies with them and shout out all their lyrics, made me realise that regardless of the lyrical content, this musical movement provides a release for the youth and gives them people to celebrate who they identify with. Drill and UK rap in general is now getting lots of young people off the roads and providing jobs and opportunities for their people. That can only be a positive. The culture of violence that’s depicted in drill music would exist if the music wasn’t there, so if the people who are caught up in a cycle of drugs and violence are spending time in the studio making music, then they’re on the right path and they should be supported.

Is there anything you think the government or authorities could do to help with some of the problems on Broadwater Farm?

With regards to the authorities, I’m not sure and it’s not really my place to comment on. The government on the other hand needs to do the same things on the Farm as they need to do in all deprived wards across the country. Show the youth a brighter future and invest in the community, rather than slashing resources and support networks that help keep young people from a life of crime. When the government close youth centres and employment schemes, stop providing EMA grants and triple university fees they are actively blocking legitimate paths to success for people who haven’t been born into opportunity. If they think this isn’t the case, then they’re mad.

The mainstream media need to start highlighting the positive things going on in the community too. It’s no good just running features on new coffee shops and nightclubs that have been set up by middle class residents but ignoring the rest of the community unless they want to report on a murder or something negative. It’s this type of institutional racism and classism that perpetuates the problem and creates further division.