The lesbian bar the people made happen

La Camionera is the only FLINTA (female, lesbian, intersex, non-binary, trans and agender) owned lesbian bar in London. Now it's putting down permanent roots.

Society

Words: Arielle Domb

Photography: Lydia Garnett

It was supposed to be a low-key party.

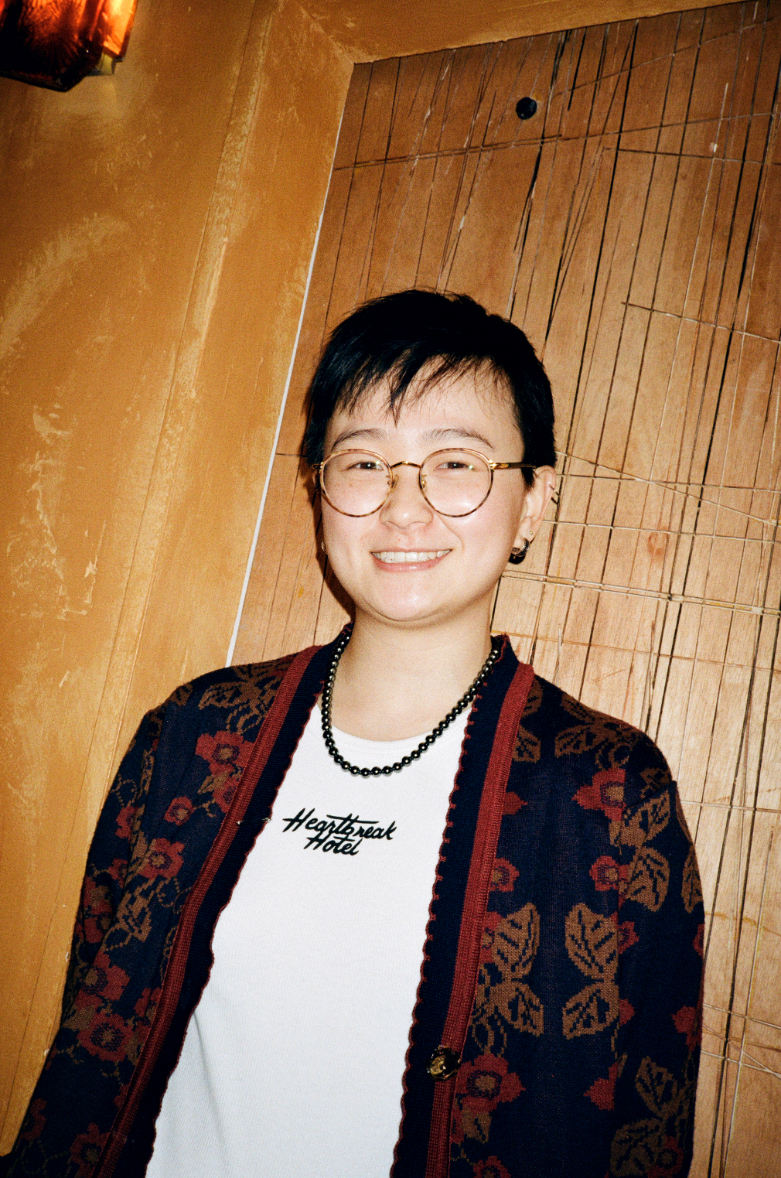

Alex Loveless and their partner Clara Solis had no idea the opening of their lesbian pop-up bar, La Camionera, would become a viral TikTok moment: hundreds of sapphics spilling out the venue, commingling with their exes and their exes’ exes down East London’s Broadway Market.

But clutching cold pints outside, in the middle of February, it was clear that something was happening: “The whole street is full of lesbians!” a friend excitedly yelped to the couple.

Nearly half of Gen Z Brits identify as something other than straight. And yet, La Camionera is the only FLINTA (female, lesbian, intersex, non-binary, trans, and agender) owned lesbian bar in London (the other, She Soho, is owned by a man).

It represents a milestone for London’s lesbians. But given queer nightlife’s thriving communities across the country – not to mention the fact that it’s, um, 2024 – why does that still seem like a novelty?

I meet Loveless and Solis in what feels more like a building site than a bar. Following that first, viral pop-up evening in February, the pair threw themselves into the search for a permanent space for La Camionera, launching a crowdfunding campaign that brought in around £30,000 in the first 24 hours.

“It was crazy,” Solis says. “There’s nothing like it in London, so people wanted to make it happen.”

Recruiting an army of lesbian builders, designers, plumbers, and gardeners, the pair set to work on a new Hackney venue, inspired by the local joints in La Mancha, southern Spain, where Solis’ family is from.

“When it’s done it will be really nice,” Loveless laughs, as a team of builders drill behind us.

Sat on two windy wooden chairs by a wall of white tiles – which Solis has hand-painted with erotic blue bulls – I ask the pair about a recent Instagram post addressing a flurry of comments asking whether the bar would be open to other demographics in the LGBTQ+ community.

“I often don’t feel super welcome at queer nights […] unless I really change myself,” Loveless, who is trans, says. “I would go into these spaces where they’re like, ‘Ooh, yeah, trans people are so welcome,’ but they’d look me up and go, ‘What the fuck are you doing here?’”

The bar’s opening comes amid a wave of trans-exclusionary legislation in the UK, from banning inclusive language in NHS documents to cracking down on gender-neutral toilets.

Even within the LGBTQ+ community, trans people are othered. The UK’s first lesbian members club, the L Community, is set to open in Southwark later this year and is excluding trans women from joining.

“Why do we have to capitulate to these definitions that no one can agree on?” Loveless continues.

“If you want to come [to La Camionera], come here. I want to set a precedent that you shouldn’t have to explicitly [specify what you identify as].”

It doesn’t take us to point out that queer nightlife in the UK is facing significant challenges.

Queer venues have been disproportionately affected by soaring rent and the cost of living, with six in 10 LGBTQ+ venues closing between 2006 and 2022. According to Pink News, by the end of 2023, She Soho was the only lesbian bar left in London. In the entirety of the UK, there were only three.

But it wasn’t always this way. As early as the 1940s, London’s lesbians would congregate in the dark cellar of The Gateways Club on King’s Road, Chelsea, decades before being gay was even legal.

“It was pretty much the only safe place to pick someone up,” says Lisa Power, co-founder of charity organisation Stonewall. “Making passes at women, unless you were absolutely dead certain they were another lesbian or at least bi, was a really risky thing elsewhere.”

The secret establishment became the longest surviving lesbian club in the world, frequented by the likes of former BBC Radio presenter DJ Ritu, artist Maggi Hambling, and Patricia Highsmith (who wrote the pioneering lesbian novel Carol in 1952). For some, however, The Gateways wasn’t radical enough. The nightclub banned the Gay Liberation Front from meeting there and prohibited political fliers from the premises. (Power once got chased out of the club for putting up a poster with the word “lesbian” on it.)

In the ’90s, lesbian bars began popping up in Soho. Jacquie Lawrence, director of Gateways Grind, a documentary about the historic venue, and London’s longest-surviving lesbian club, would spend her Saturday evenings at the neon-pink lit Candy Bar, where lap and pole dancing took place. “Lesbians weren’t afraid about talking about sex anymore,” Jacquie said. “It was a real celebration of the lipstick lesbian… a break from the butch/femme kind of trope.”

Lesbian parties spread to North London during that decade, too. Stoke Newington became known as a lesbian mecca, birthing bars such as Blush and Oak Bar. In Dalston, a clandestine burlesque club emerged in a derelict Chinese restaurant, serving £1 vegan food. Then, there was the Glass Bar, a hidden enclave filled with velvet drapes and fairy lights just outside Euston Station.

For Nancy Kelley, director of lesbian visibility week and executive director of lesbian magazine Diva, the bar was a sanctuary from the violent homophobia she experienced on the streets. “It had this really magical feel to it,” she recalled. “It was like entering a doorway into a different world.”

However, even within these ostensibly progressive scenes, racism was rife. Women of colour were sometimes turned away at the door, only to see a group of white women enter immediately after.

In 1985, the same year The Gateways Club closed its doors, DJs Yvonne Taylor and Eddie Lockhart set up Sistermatic – a Black lesbian-run sound system that ran monthly parties in South London Women’s Centre in Brixton.

Towards the turn of the century, however, venues began disappearing. Sistermatic closed in 1995 (the Women’s Centre lost its funding). The Glass Bar closed in 2008 (the landlord tripled the rent and backdated the rise). Candy Bar closed in 2014 (their rent was doubled).

“Lesbians didn’t – and don’t – have the economic power that gay men or straight couples have,” says Power. “That’s really the problem in tracing the history of lesbian clubs. Apart from The Gateways, most of them didn’t last that long.”

On the one hand, the lack of permanent LGBTQ+ venues has given rise to an eclectic DIY scene, pioneered by communities who have felt othered in white, cis-male dominated spaces.

“I think the label of ‘queer’ became a catch-all, which means that some specificities get lost and the needs of specific communities get lost,” says Rabz Lansiquot, co-founder of the South London, BPOC-prioritised party WET. “Those communities have felt like they need to create their own spaces.”

The options are dizzying. Sex-worker-led Sex and Rage throws lesbian strip club parties in Dalston. Meringue celebrates fat, queer culture with kaleidoscopically chaotic parties (think: glitter streamers, inflatable doughnuts, and a – gluten-free – pie eating contest). Last year, Sistermatic teamed up with Nite Dykez to revive their iconic sound-system parties, bringing generations of Black lesbians together for a “musical journey” spanning lovers rock, dub, and ballroom.

Still, without permanent venues, running queer nights can be challenging. “We’re always in basements,” said Becca Homer, who runs the East London dyke party Strapped and 537 Events. “Venues never give us a weekend night because they think that lesbians only love to crochet.”

Not having a permanent venue also means being at the mercy of the building owners and staff, who aren’t necessarily queer themselves. For many organisers, this means having to go over LGBTQ+ and disability inclusion protocols before every party.

“We’ve had so many problems with security over the years,” said Nadine Noor, founder of the QTBIPOC club night PXSSY PALACE. “One of our main producers is a trans woman and they’ve been transphobic to her before.”

Some have responded to venue challenges in creative ways. U Haul Dyke Rescue has built an old-school America-inspired portable van that will rock up at parties and festivals, serving pints and hosting arm-wrestling matches.

But as Noor puts it: “We as queer people have constantly lived in the temporary. We need permanent spaces [too], because when you have something permanent then you’re able to grow roots.”

On a balmy evening in May, La Camionera finally opened its permanent doors.

The building was still rough around the edges, sure: the toilet didn’t yet have handles (they’ve since been fitted), and the food menu had yet to begin. But with tiny vases of pink and purple purple flowers, takeaway pizza, and a portable speaker playing sweet, sugary tunes, London’s second lesbian bar was already a success.

The team is now waiting for a court hearing which will determine their licence (right now, they’re only allowed 36 people in the venue). But Loveless is looking to the future.

“I just hope that people continue showing up,” they say. “The whole idea behind the project was to make a permanent space. I really want that to have longevity.”