On Stage. Front Page. Every Show I Go.

Volume 4 Issue 002: B-ballers, hip-hoppers, acid jazzers and singers from Manchester called Ian... For its 50th birthday, we pay tribute to the adidas Superstar – a shoe nestled at the intersection of sneakers, streetwear and rap.

Style

Words: Calum Gordon

Photography: Lawrence Watson

Article taken from The Face Volume 4 Issue 002. Order your copy here.

The first and only time I met the late fashion writer Gary Warnett was in the back of a taxi in Berlin. I’d voraciously consumed his hyper-nerdy streetwear blog, Gwarizm, for years. Within two minutes he launched into a spiel about an obscure Russian adidas advert from the 1980s and asked if I remembered it. I didn’t, but nodded anyway, so as not to disappoint him.

Warnett was an oracle when it came to matters of sneakers, streetwear and rap. So, naturally, when asked to pay tribute to the significance of the adidas Superstar – a shoe nestled right at the intersection of those three topics – Gwarizm was the first port of call. Unsurprisingly, buried in the archives of the website there was his own “brief history” of the shoe – coming in at just under 5,000 words. Warnett was rarely one for brevity when it came to discussing the minutiae of sportswear.

Most articles that have appeared since about the adidas Superstar are just reworked versions of this original opus.

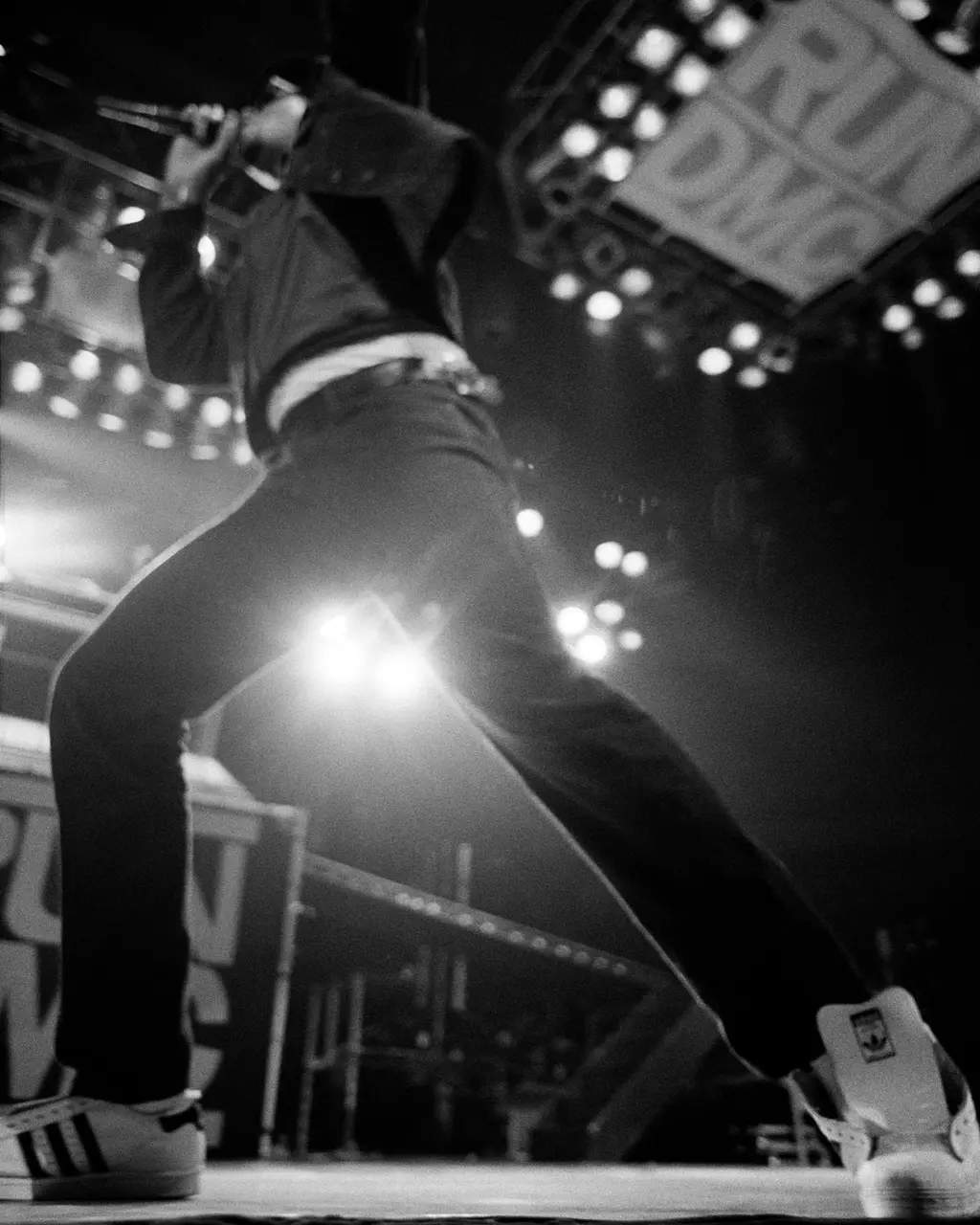

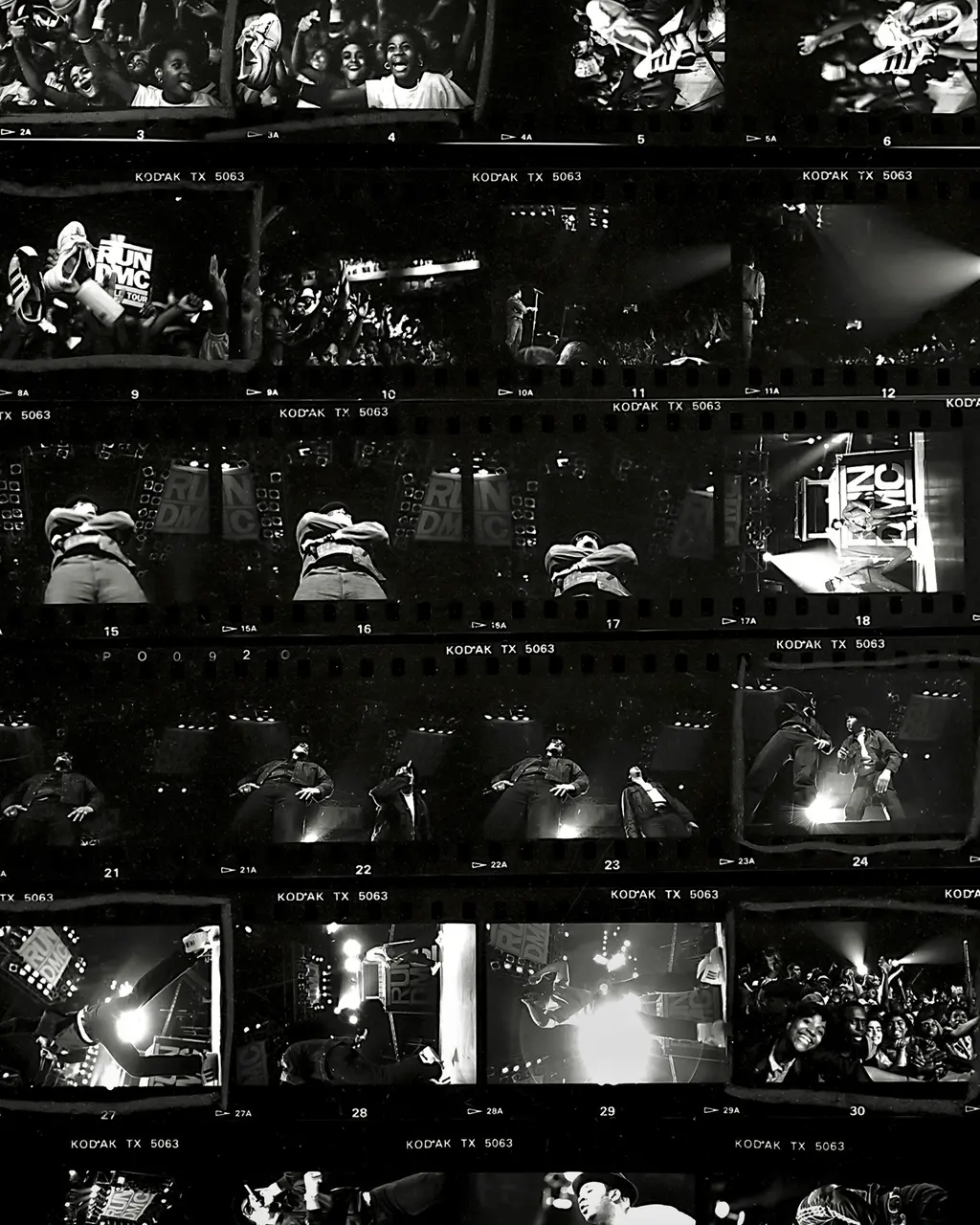

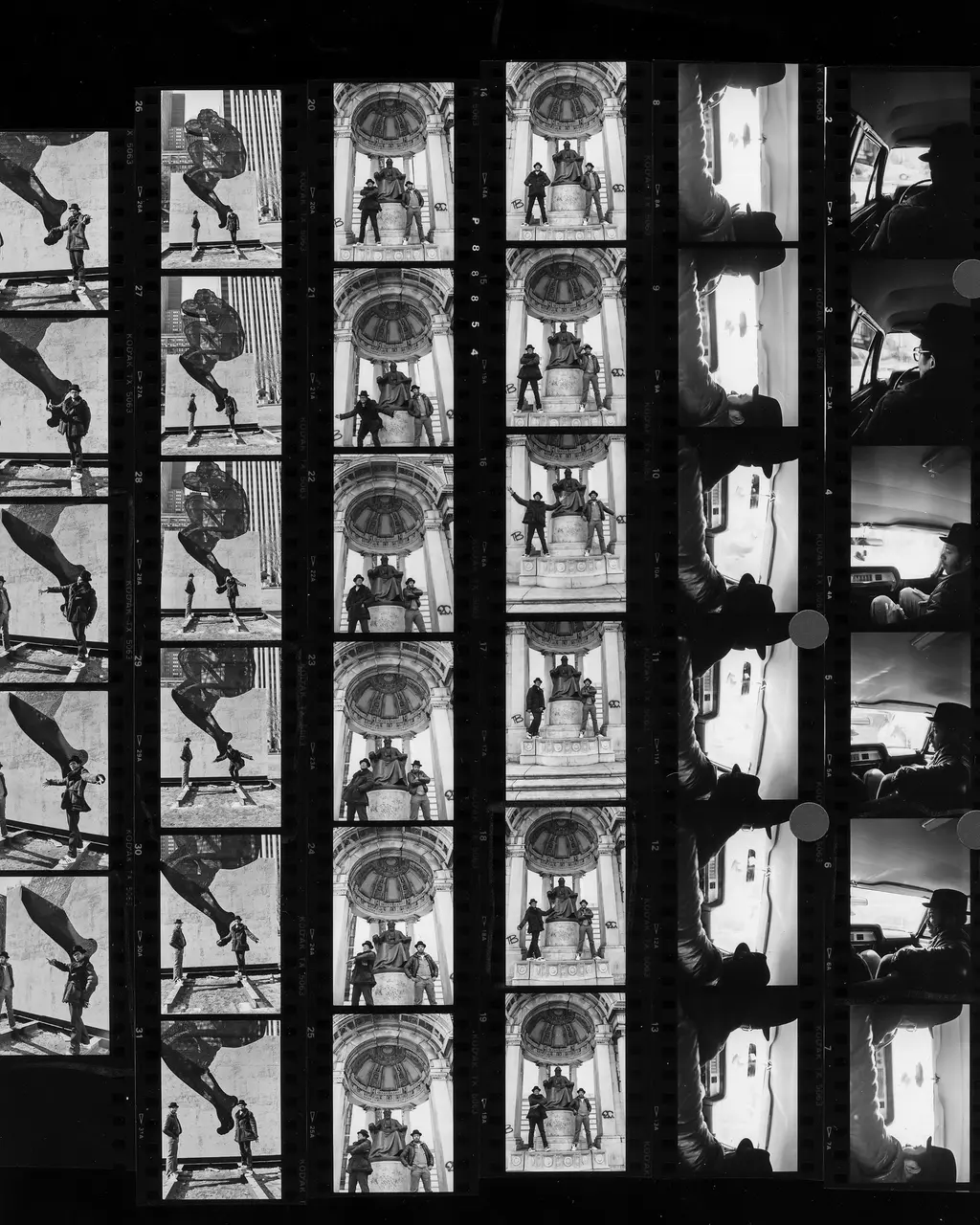

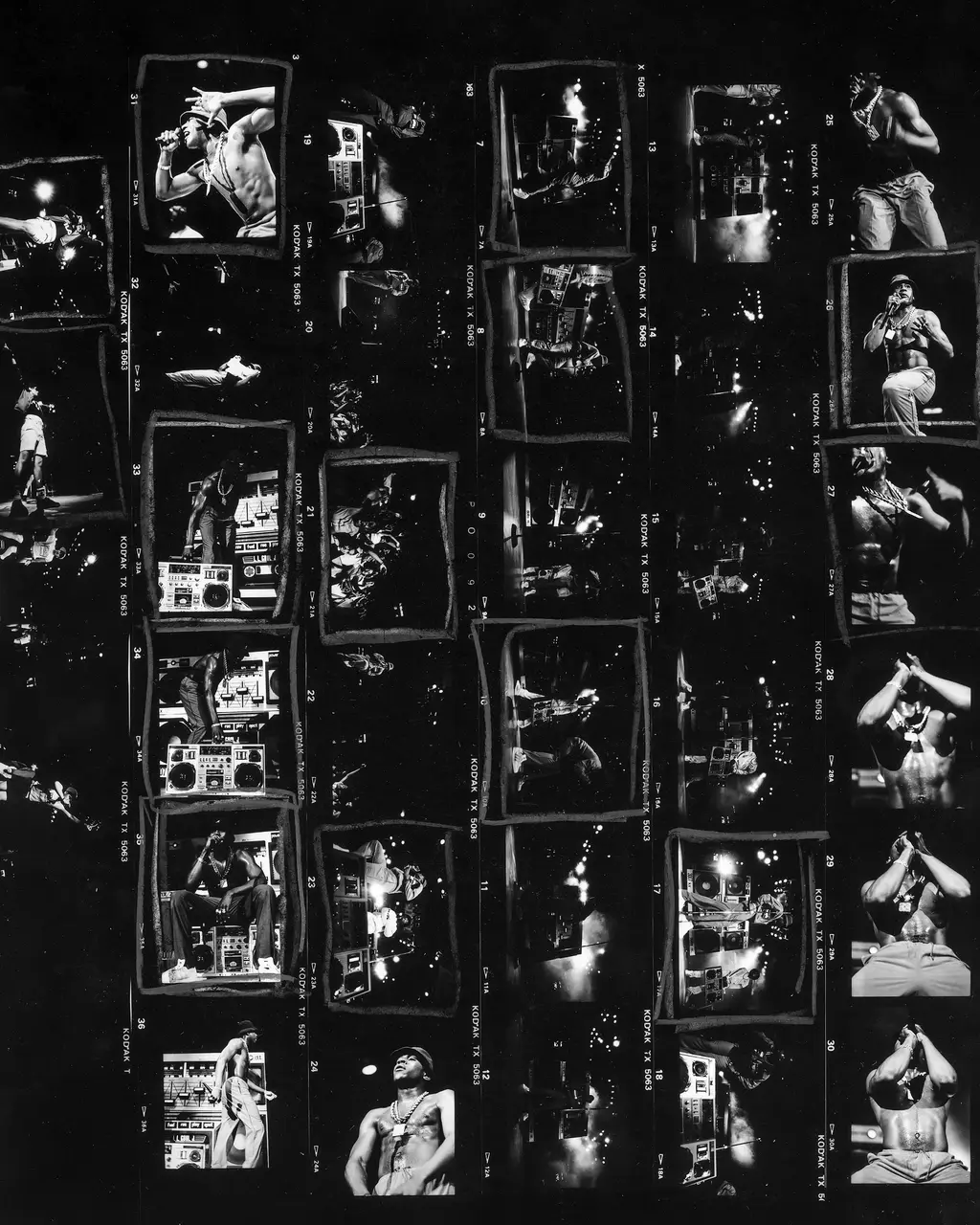

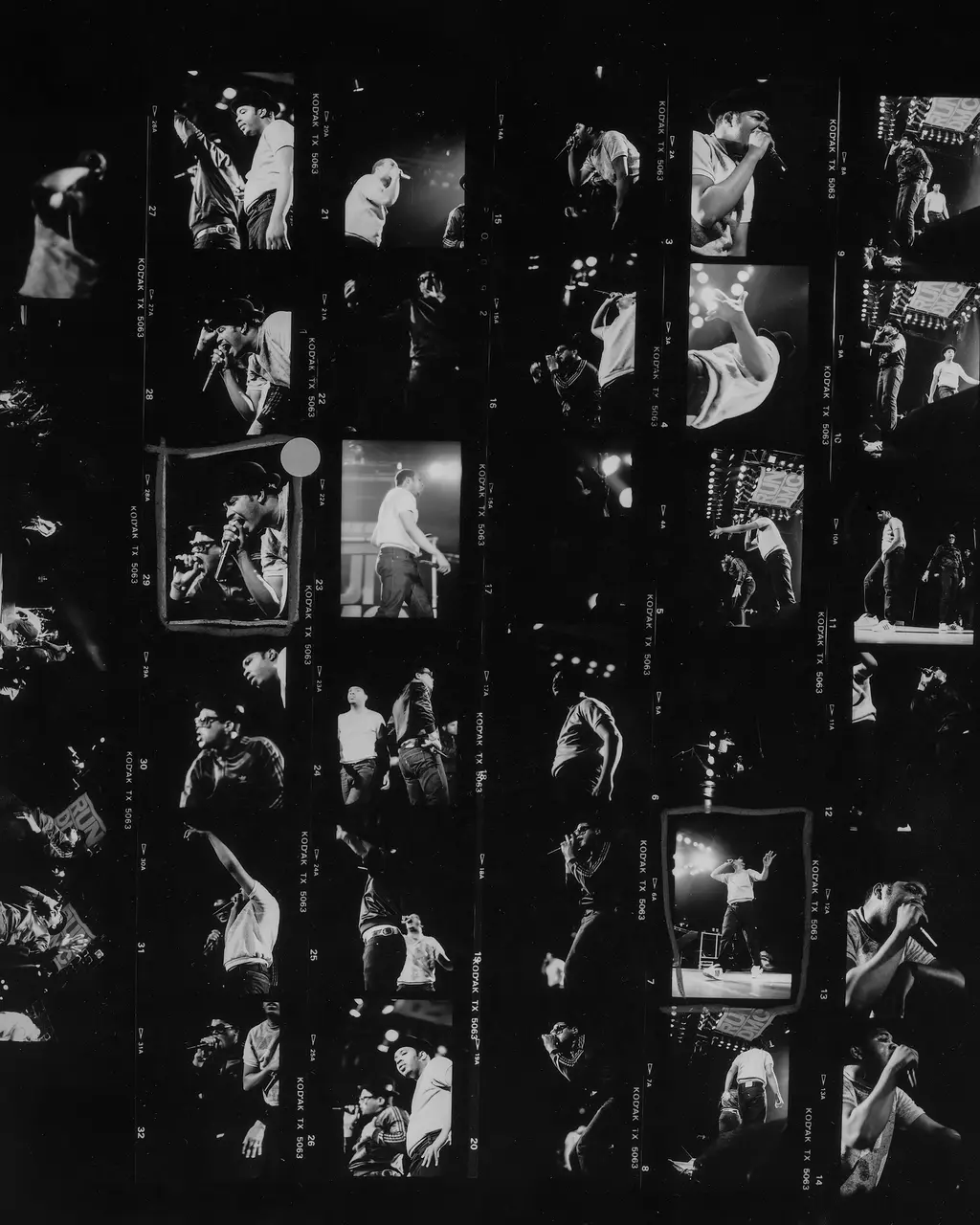

Run-DMC on the Def Jam tour, 1987

Run-DMC on the Def Jam tour, 1987

Some facts about the shoe that only Warnett, and a handful of adidas archivists, would know. Chris Severn, an American distributor of adidas, was instrumental in convincing the brand to open up its footwear offering to meet the needs of various American sports, including basketball, paving the way for the Superstar in 1970.

The adidas Superstar’s design was an evolutionary process, borrowing elements from other shoes, such as the Supergrip and the Pro Model.

In France in 1968, as students flipped through Situationist International pamphlets, something with a similarly revolutionary spirit would appear in that year’s adidas France catalogue: a shoe that perhaps most closely resembled the Superstar as we know it today.

-

“People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.” “People went apeshit crazy for it.”

Despite its European origins, the adidas Superstar feels as quintessentially American as French fries. There are four people closely associated with the shoe: the three members of Queens rap group Run-DMC and basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, whose career in the NBA spanned two decades, starting in 1969.

Jabbar was the original “face” of the Superstar, signing a deal with adidas in 1976, but he was not the first to wear it. The San Diego Rockets’ coach, Jack McMahon, convinced most of his team to switch to the Supergrip in 1969, after three players had been injured by slipping in their canvas sneakers. By the mid-1970s most of the league teams were playing in Superstars.

The shoe’s story would veer away from pure sporting endeavour in subsequent decades, until adidas brought things full circle in 2003, releasing the Superstar 2G, which was favoured by emerging basketball stars, including LeBron James.

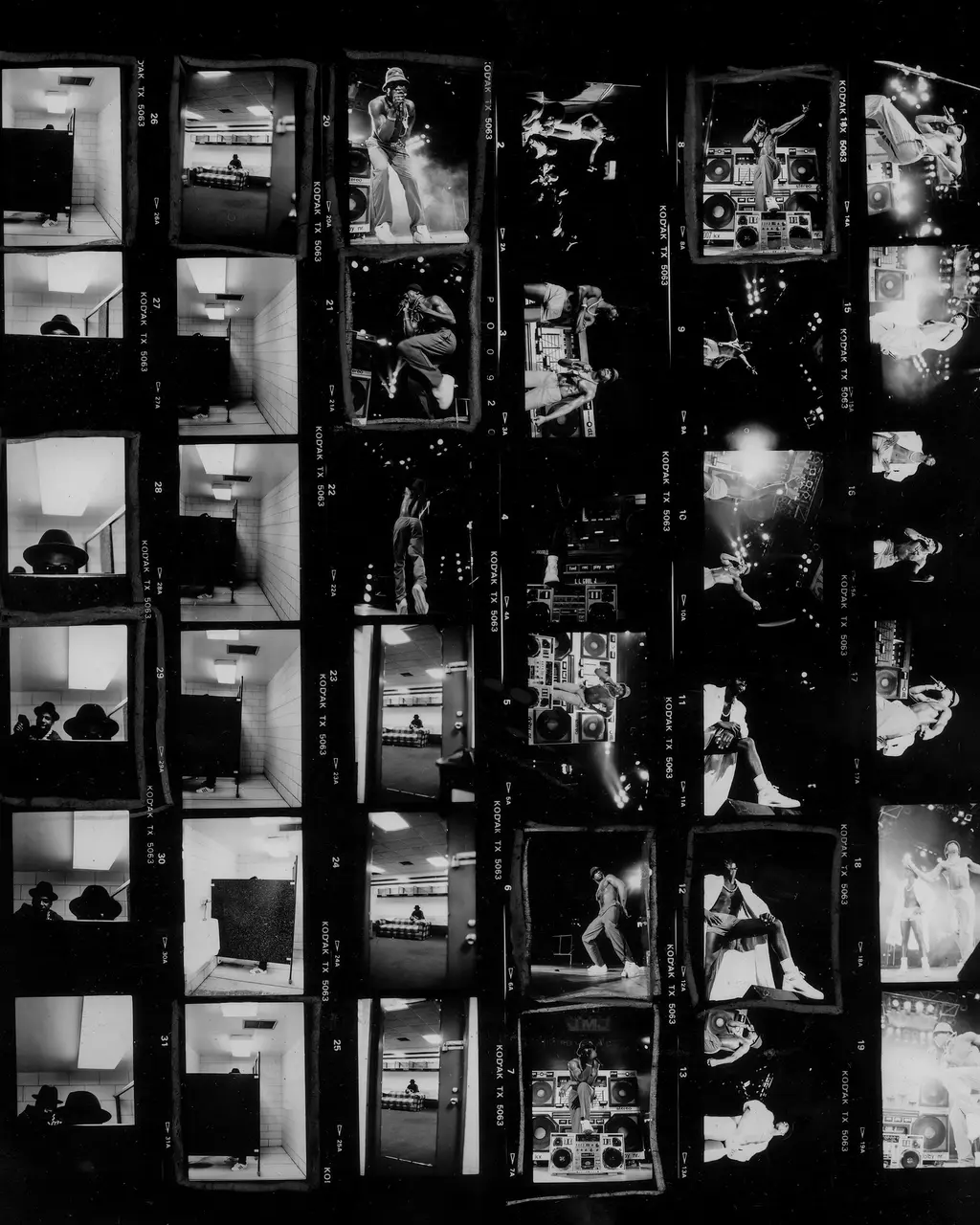

Run-DMC, the pioneering hip-hop trio of Jason Mizell, Darryl McDaniels and Joseph Simmons, cemented the shoe’s iconic pop cultural status in the mid-1980s, in what would be a precursor of deals to come. Today, a rapper collaborating with a sneaker company raises few eyebrows. But Run-DMC’s deal with adidas, valued at around $1 million, set a precedent. It came off the back of adidas marketing executive Angelo Anastasio attending a packed Madison Square Garden and witnessing rapt fans each holding a single shoe aloft, identifiable by its shell toe and fat laces, as the group performed their track My Adidas.

That song, too, has modern day parallels, with Kanye West boasting in 2012, and again in 2015, that his Yeezy brand “jumped over the Jumpman”. My Adidas was arguably hip-hop’s first footwear-orientated rap beef, with the song coming as a riposte to Jerrald Deas’ track Felon Sneakers, which derided Run-DMC for wearing their Superstars without laces – how prisons insist inmates wear their shoes.

By the time Run-DMC released My Adidas in 1986, it provided a sort of second wind for the shoe. The Superstar had already been a staple within New York hip-hop circles since the turn of the decade. A 1984 episode of a cable TV show called Graffiti Rock, which adopted an educational approach to this emerging subculture, outlined the uniforms of both the B‑boy and B‑girl in an interview with two breakdancers, Rosemary and Dino, both wearing three-stripe shell-toes. “These are a pair of adidas with the fat laces. That’s the way we sport them,” Rosemary told the host. The shoe also made a fleeting cameo in Malcolm McLaren’s 1982 video for Buffalo Gals, which featured the Rock Steady breakdance crew.

In London during the 1980s the shoes also found an appreciative audience in the emerging rare groove and acid jazz clubs. Simon “Barnzley” Armitage, a denizen of London’s fashion and club scene during that era, remembers travelling to the US to buy up dead-stock Superstars and bringing them back to the UK. “I’d get them from a Korean guy, Mr Kim, and smuggle them through customs,” he recalls. “The ones to get were black with white toes – not so common. We’d wear them with Levi’s and Double Goose leather puffer jackets. I remember a few of us also had leather tracksuits. Although not many will admit it, they’d be worn with fake Louis Vuitton jackets and caps, fake Chanel T‑shirts, patched jeans and NYU Champion hoodies.”

Meanwhile, in Japan, there was an audience whose appreciation for the Superstar had spilled over into fanaticism. Ever since the 1970s, the exorbitant price of the shoes lent them a certain allure for Japanese collectors. By the 1990s small US newspapers were running ads offering up to $100 for pairs of rare Hungary- or French-made Superstars lying around in people’s attics. They’d then be flipped for a 500 per cent mark-up in Japan.

That culture of Superstar collectors was perhaps best encapsulated by the 2003 adidas collaboration with Japanese streetwear brand Bape, which resulted in two iterations of the Superstar: a reworked version of the classic and a skate version. Oddly, the partnership came about through an introduction from The Stone Roses’ Ian Brown, who released his own iteration of the Superstar in 2004, marking the shoe’s 35th birthday.

“We had one of the biggest queues outside the store to date,” recalls Craig Ford, who ran London’s Bape store at that time. “People went apeshit crazy for it.”

The simplicity of the Superstar has lent it an amorphous quality, similar to that of Carhartt work jackets or Levi’s 501s, allowing it to deftly traverse various cultural scenes during its lifetime. In the 1990s it was worn as a skate shoe by the likes of Kareem Campbell, Keith Hufnagel and Mark Gonzales. (The latter has released his own collaborative Superstars with adidas in recent years.)

More recently, it has been reworked by both pop culture icon Pharrell Williams and avant-garde fashion designer Rick Owens. Few products could better encapsulate the current aesthetic language within fashion, best defined by its streetwear-leaning, bricolage tendencies. Indeed, the Superstar’s own iconic status is an amalgam of the very same reference points that gave rise to streetwear: hip-hop, skateboarding and sportswear.

The Superstar was, and still is, a cultural signifier. Prior to its introduction, running shoes had been made to sell to runners, and basketball shoes made for basketball players. The Superstar changed that, and what was felt underneath its sole was ever-changing: hardwood floors, Harlem streets, London dancefloors and skateboard griptape. It’s a shoe that has defied categorisation, but in each respective scene has been embraced, serving as proof of authenticity. As Gary Warnett showed, screeds of texts could be dedicated to the Superstar’s history. But what’s just as interesting are the parts of the story that are yet to be written.

In memory of Gary Warnett. Thank you for the knowledge.