And Then We Danced: an instant queer classic

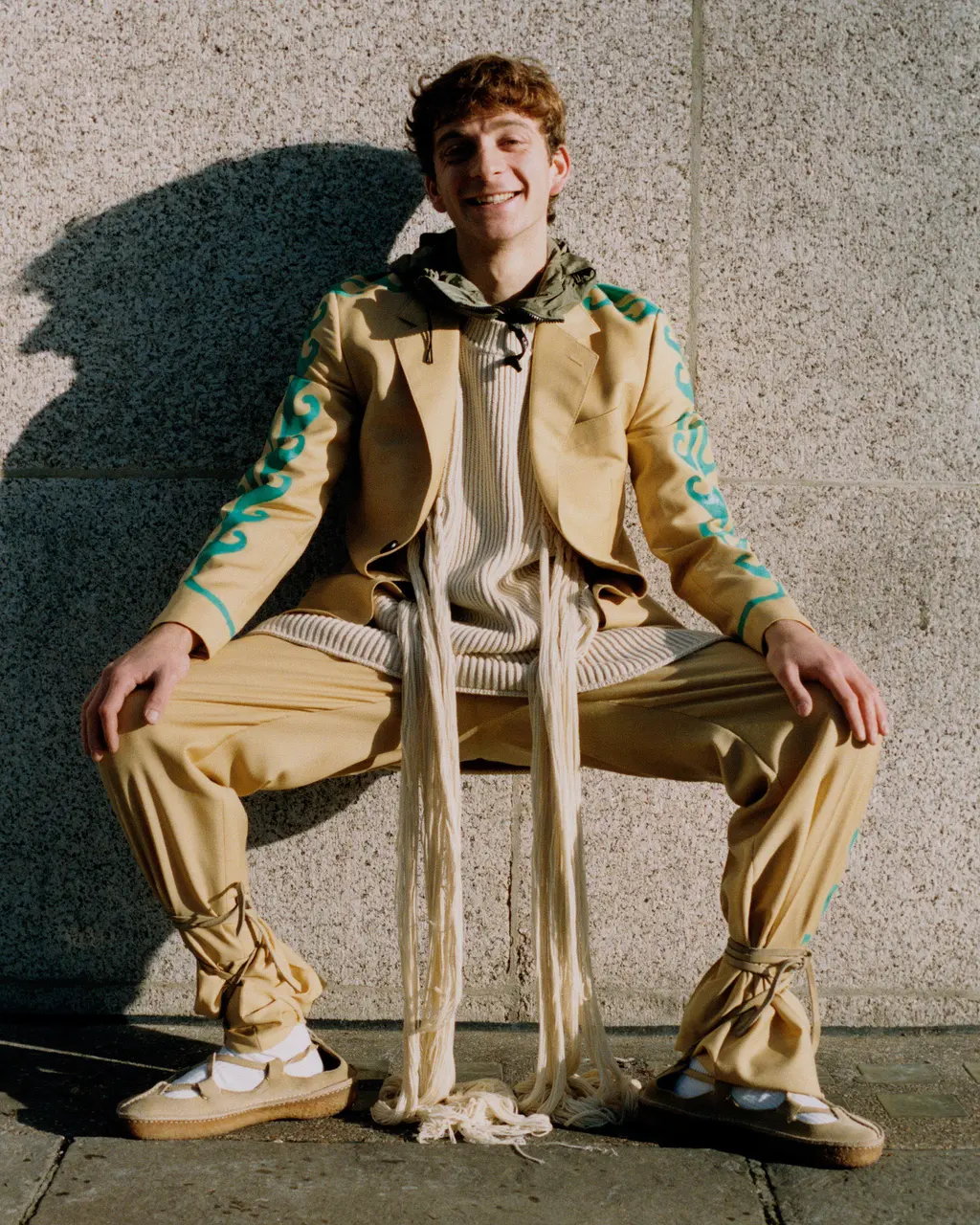

Volume 4 Issue 3: Georgian cinema has birthed a new film hero, Levan Gelbakhiani. After starring in the Tbilisi love story, And Then We Danced, the young actor has become one to watch.

Culture

Words: Douglas Greenwood

Photography: James Robjant

Styling: Hamish Wirgman

Article taken from The Face Volume 4 Issue 003. Order your copy here.

A year ago, Levan Gelbakhiani was a Tbilisi boy in limbo. A shy 20-year-old working at a Georgian theatre, waiting for a film he’d wrapped a few months earlier to make its world premiere. There was a mix of anticipation and anxiety. The film’s subject matter – queerness – was a taboo in the former Soviet republic, one that few artists had dared touch, publicly at least.

“I had a normal kid’s life,” the actor tells me in a London hotel lobby. “Today, it’s totally different.” His film has come out and it’s causing a stir. And Then We Danced is a love story built from a thousand untameable impulses. Directed by Swedish filmmaker Levan Akin (of Georgian descent) and set in a Tbilisi dance school, it follows Gelbakhiani’s character Merab. He’s a self-conscious teenager whose entire life has revolved around traditional Georgian dance – a legacy left to him by his parents. But something stands in his way.

Georgian dance is a staunchly masculine art form, one that his teacher stresses has “no room for weakness”. Yet Merab’s sensual, beguiling fluidity is pulling him towards something different. He’s the class outsider, until a new student walks in: a tall, handsome boy named Irakli. Merab finds a partner, and a lover, in whom he can confide.

Top, Craig Green

Suit and shoes Lanvin, jumper Jil Sander and hoodie CP Company

And Then We Danced premiered at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, was nominated for the prestigious Queer Palm, and led Gelbakhiani onto just about every notable “Hot Young Actors to Watch” list. Earlier this year the movie swept the board at the Guldbagge Awards, Sweden’s Oscars, taking the honours for best film, actor, cinematography and screenplay.

It has become an instant queer classic – a status made even more wondrous by the inevitable battle being fought against it in Georgia, a highly conservative, Orthodox Christian country in which physical violence towards LGBTQI+ citizens is not uncommon. Last year, the film’s Tbilisi premiere was locked down for safety reasons after far-Right protesters bombarded the screening.

So while he may be fêted in Western Europe, walking through the streets of his country’s capital city now feels a little different for him. “There’s been a lot of crazy people,” he admits.

Gelbakhiani is stooped forward in his seat, rolling up his sweatshirt sleeves as he speaks. He looks harmless: tall, slender and softly spoken. “When I was in the city a few days ago, people were looking at me. Some were pointing me out as ‘that guy from the film’.”

He knew this reaction was coming from the moment he heard of the project – he turned the director down five times before he said yes because he felt there was too much baggage with the role. But Akin persisted because he’d seen footage of Gelbakhiani dancing and was fascinated by the untrained actor and his “50,000 faces”.

“I had this fear but my family came to a conclusion: ‘Do whatever the fuck you want!’”

Gelbakhiani was reluctant to take on the part not only for his own safety, but also for that of those around him. “I had this fear. Behind me there were my family and friends, and they’d have to go through all this with me. I spent a while discussing it with them all, and they came to a conclusion: ‘Do whatever the fuck you want!’”

Thank fuck he did – not just for his own career but for anyone who’s had the privilege of seeing the film. He’s present in almost every frame, with the blushes of first love between Merab and Irakli portrayed with a rare queer richness of feeling. “We knew the script, but the emotion was all in the moment,” he says.

Now that Gelbakhiani’s face has been projected into arthouse cinemas the world over, he’ll be in great demand from those lured in by his part in this jubilant piece of queer cinema. I ask whether he’s staying in Tbilisi, despite the attention of more film industry-friendly (not to mention more queer-tolerant) cities.

“I’m happy there,” he insists, “but I’m not happy about the things that are happening. It’s home, and if you see all these problems and you don’t think you can change them, it’s not going to help you or anyone else [if you leave].” He’d prefer to stay put, he says, “to fight for change and freedom”. And just like that, Georgian cinema and society births its new film hero.