Ewen Spencer on the styles, subcultures and pure hedonism of British nightlife

The photographer’s new book, While You Were Sleeping, presents unseen photos from London’s clubs between 1998 and 2000. Here, the great Geordie describes the dancefloor’s pre-millennial magic.

Few cultures can boast about their partying prowess as much as us Brits. We love a pint, an U18s club night, a house party, a warehouse rave, a boozy BBQ, a wired woodland forage, a festival. And we’ll find any excuse to let our hair down and get positively shitfaced, too, from the end of exams to a pet hamster’s birthday.

And through this devotion to nightlife, subcultures have formed over the years – a merging of sonic and sartorial styles seen on sticky dancefloors night after night, year after year.

Pointing a flashy lens somewhere in the crowds since the mid-1990s, Ewen Spencer is the Geordie photographer who made a name for himself capturing the British club scene he was immersed in. Then a recent art school graduate, Spencer took his Northern Soul roots and love for going out, and turned his attention to the fast-changing scenes in London.

“At the time, London was very optimistic, with a new government,” recalls Spencer. “It sort of predated tech and was hedonistic and unabashed. People went out and they wanted to have a good time.”

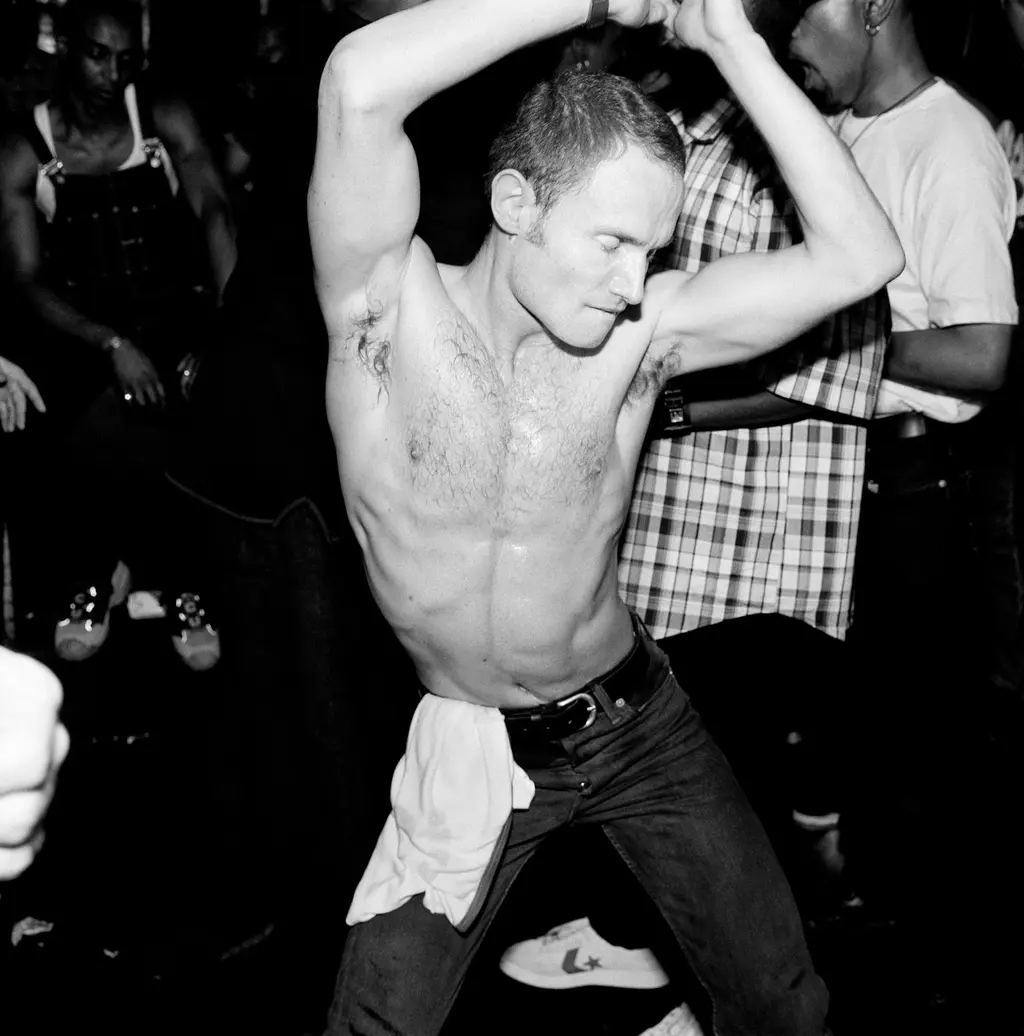

In no time, he found himself darting from club to club, documenting the cool kids out and about on Friday nights. But his photographs captured more than young people off their ’eds. They recorded a moment in time: the clothes the party-goers are wearing, the lack of phones glued to hands and the fleeting moments in hidden corners that make up a class night out (eyes wide open).

Soon enough, Spencer started shooting for Sleazenation and THE FACE, both of which were also publishing subversive takes on British youth culture. Spencer’s shots – sweaty, intoxicating, at times humorous and sometimes romantic – were a precise depiction of what was happening on the streets of London, during the peak of a major culturequake across fashion, music, film and sport.

Now, Spencer is releasing a book, While You Were Sleeping, which was designed and includes text by Sleazenation alumni and legends Scott King, Justin Quirk and Elaine Constantine. Focused on images taken between 1998 and 2000, it tells the clubbing history of London at the turn of the millennium, a “high point” in Britain’s nightlife history, as he puts it.

Spencer has long honed in on specific subcultures. He’s released UKG, a book dedicated to his time recording UK garage raves in the early-’00s; Young Love, focusing on the pursuit of, you guessed it, young love in the club and Open Mic, which documented the grime scene in 2012. He’s photographed the cast of Skins, Bristol rockers and even posh kids holidaying in Devon. But this mash-up of unseen photos reads more like a visual document of the British high street once the lights go out, all intermingled and harmonious, as rave intended.

Above all, though, it’s a celebration of the tenacity of young British people and how, in the face of anything, we know how to party. We caught up with Spencer to pick his brains about the book, the rise and fall of drugs, what ’90s kids were really wearing, and the beauty of being young and full of beans in Britain.

Hello, Ewen! Congrats on the book. It’s coming out at a pivotal time, I feel. Clubs have been open for a while and people are feeling fairly optimistic about the upcoming summer, even though it’s pissing it down right now.

It’s good that you’re feeling the same way! It feels like it’s a good time for the book to come out and help people feel encouraged to get out again. Where have you been going out?

Mostly Venue MOT in Bermondsey.

I was down there a couple of weeks ago.

It’s ace, isn’t it?

I was taking some pictures, actually. It’s got everything needed for a good night out. I was also at Guttering on Saturday.

Bet you got some good photos at that one. So, who is While You Were Sleeping for? There’s the nostalgic side, for the people who were actually at those nights. But then there’s also the other side. I wasn’t there, but I love looking at these pictures of nightlife history in the UK.

The smart answer is that there’s no prejudice or bias. The book is for anybody who wants to look at it and it’s down to anybody to make their own mind up on why it exists, or otherwise.

There’s the idea that people are feeling more optimistic and like they want to be out and about again. I feel that there’s going to be a tidal wave of that happening, because we’ve been penned up for so long. British kids are good at subcultural context. They like to party and they know how to do it, reinventing or creating a look or a style to combine with music and a place where people come together and congregate.

Where were you at in life when you were taking these photos?

I had just graduated and that was my first foray into fashion editorials, style and nightlife. While I was studying, I’d been taking pictures around the Northern Soul scene, which was very much my world, my subcultural moment. And so I just transformed that into this moment, mainly around London.

“We always kick against the pricks, don’t we? We are the mothers of invention, we want to create something out of nothing because that’s just what we’re used to”

EWEN SPENCER ON BRITISH YOUTH

There’s a lot of dialogue about how subcultures don’t really exist anymore. I don’t believe that. I think subcultures are everywhere, they’re just a lot more cross-pollinated. When you’re going to club nights taking photos now, what trends are you noticing?

There’s a cross-pollination, but they also happen quicker. They manifest very, very fast and perhaps dissipate or then converge elsewhere quicker. It’s easy to throw it away and say, for instance, in Guttering a lot of the kids look quite emo. But then what I also see is people also responding to things like Euphoria, and a kind of idea of what Y2K was in terms of style.

There’s also an influence of Japanese anime cosplay mixed with something that’s quite emo. That has always existed, but in certain areas, there’s a real overt determining of sexuality and ambiguity within that. That always existed in clubs, since I was about 15. We had to go to gay clubs to find the music that we wanted, even though we were young, straight men. At that time, if we wanted house music from Detroit and Chicago, we had to go to gay clubs to get it.

Ah, we gays know good music.

You do! What I see is people being more conspicuous in their sexuality. And the ambiguity around that is slightly contradictory. But that’s just my perception. And then there’s more… I don’t know how legal this is.

Go for it, Ewen.

Well, I’m noticing a less convert, more conspicuous consumption of narcotics. And that, for me, is alarming. Sorry, not alarming – it takes quite a lot to alarm me these days. It’s surprising. And I was only surprised because when I was out raving, [the use of] narcotics was something that was very covert.

I don’t know if it was about us as young, working-class men, but we didn’t want to be seen to be off our heads. We wanted the feeling and the excitement that the music and the hiving of people brought with narcotics – but we didn’t want to be seen to be doing that. It was something that you hid away. And what I’ve seen in the contemporary [scene] is something that’s more conspicuous.

What a time you were shooting, Ewen. Was it as hedonistic as younger generations are led to believe?

It was hedonistic, but it was full of joy, as well. I think what contributed to the hedonism was the fact that the city was changing dramatically. Places like East London were still very residential. But people were starting to set up club nights because it was more affordable to rent those spaces out, so people started moving into that area.

Do you remember anywhere in particular?

In the mid-’90s, when I first went to Hoxton Square, it was to the Bass Clef, which became The Blue Note. There was nothing else in that area, though you might have got your head kicked in. It wasn’t just East London that was happening, it was bubbling everywhere. And you had a lot more ecstasy and cocaine, a lot more people going out with that in their mind.

The city was changing a great deal and it was reflected in people’s attitudes when they were going out. You used the word optimistic earlier and it was a very optimistic time. It was very celebratory, and you can probably see that in the pictures.

Young people in Britain often feed off politics: when it’s all going to shit, we make our own fun. I think that’s very much what’s happening now. We have a Tory government, Brexit, cuts, inflation, the rising cost of living – but also great parties and new styles emerging.

We always kick against the pricks, don’t we? We are the mothers of invention, we want to create something out of nothing because that’s just what we’re used to. There’s not a lot left for British youth, but we don’t half make something out of it.

We do. Are you noticing any parallels from that time compared to now?

That’s really tough, because I think kids are less resilient now. They still want to make something happen and I think they are, but working-class culture probably was more predominant back then and perhaps less so now.

Working-class kids are demonised a bit too much now. They’re blamed for Brexit and things like that, and I think it ebbs away the confidence of young working-class kids. They probably have less incentive to go out and do things in the way that they did in the ’80s and ’90s. That’s a bit of a shame, really.

It’s probably not a very popular thought, but those are my feelings on it. It’s something that I see and I miss, if I’m perfectly honest with you.

I guess social media has us all wanting to keep up appearances, in a way. And maybe there’s less freedom to enjoy yourself without prying eyes now.

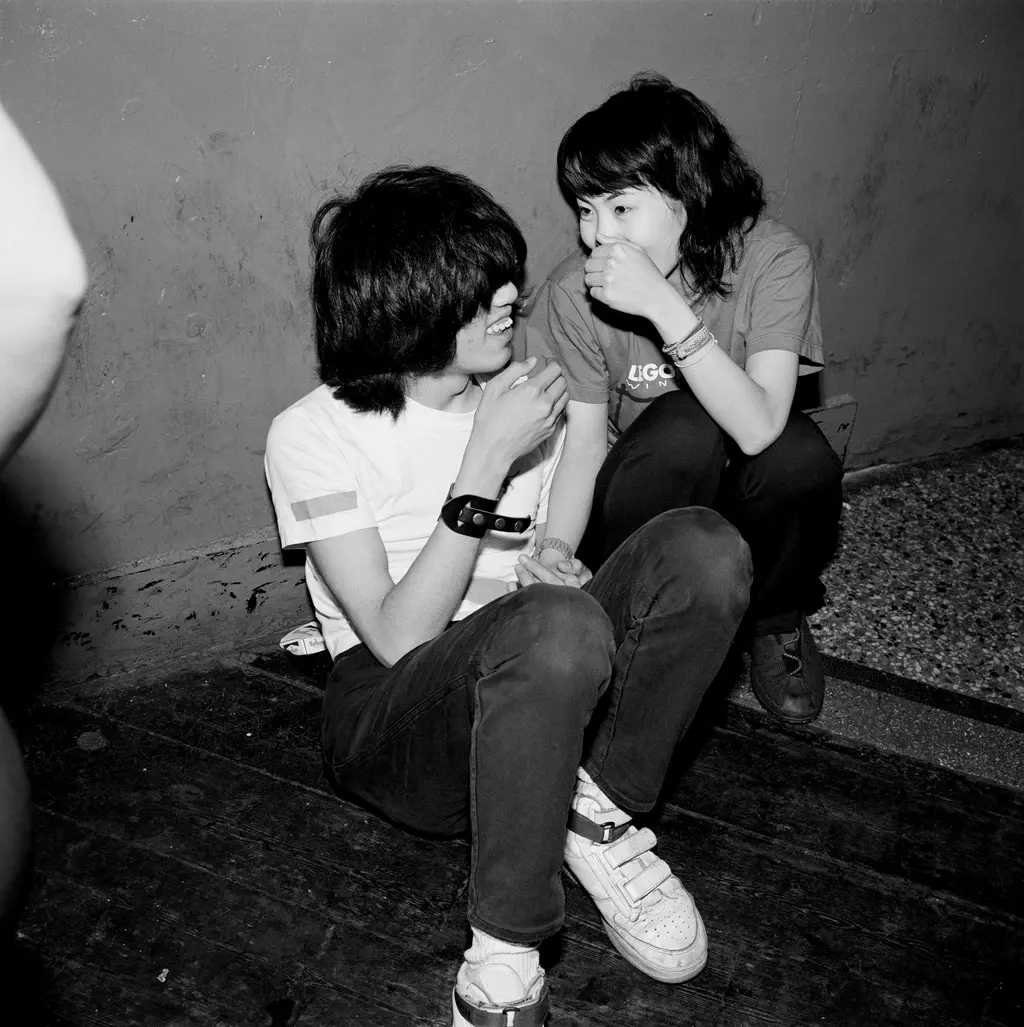

That’s an interesting point. My kids tell me that the most revolutionary thing you can do right now is to get off-grid. One of the interesting things I see when I’m out in clubs is quite a lot of kids who are not on their phone – nowhere near their phone and not wanting anything to do with it. When I see kids doing that, I think: fantastic. They’re just dancing together. When they haven’t got them out, they’re just sitting around talking.

Whether they’re loaded or not, I don’t know. But they’re either sitting around talking in the smoking area, going bananas on the dancefloor, or they’re necking on and getting into each other, which I thought was brilliant at some of the places I’ve been. To see that again was really great.

“More men give a shit about dressing well now than they did then. A lot of geezers would just put a YSL shirt and some jeans on. It was awful. It’s quite nice to see that blokes make more of an effort now”

EWEN SPENCER

So, the revolution is going to be us lot putting away our phones?

Yeah, I get that talking to young people. Back then, we tried to change things by raving. We used our vote to maintain a Labour government. They weren’t perfect but fucking hell, it’s better than what we have now.

How important was appearance back then? A huge part of UK garage was about how you dressed. But what about those clubs you were going to, like those in this book?

The clubs in East London, like 333 or spontaneous parties on Brick Lane, you’d still get tribes and people with a certain look and aesthetic. In the 333 upstairs, you’d get Sonic Mook Experiment, for instance, and a lot of the kids there would be interested in a Japanese or Americana-type look, that Michael Koppelman introduced through his shop, Hit and Run, in Soho. And so we’d go down there and buy pieces by Let it Ride, Good Enough and BAPE. That was around ’97.

Those pieces must have been groundbreaking back then.

It was! It was groundbreaking. Silas was also big. It was a bit Mod, because you had to know what it was to get it. Otherwise, you would just look like a kid in a sweatshirt and a pair of Levi’s.

The material was always really amazing quality and there might have been a really killer, boxy shirt worn under a sweatshirt. A lot of people weren’t wearing that at the time. But when kids did wear it, it was a bit different, away from hoodies and that sort of thing – that varsity Japanese crafted look. And then you had other kids who were a bit more of a mainstream version of that. And then kids who were into garage, wearing Moschino and Iceberg.

And that was all about appearances, keeping labels on jeans and all that, as my brother did.

There was a lot of that, but it happened a bit later on, that overt display. When I first started going to garage raves, it was quite a narrow silhouette. You would never see anyone wearing full Moschino. If you did, they were a drug dealer, simple as that.

You’d see people wear bits and pieces of it and it looked great, but they mixed it up with French Connection, Giorgio Armani, Stone Island and all sorts – it was a real mix. The kids wearing Stone Island and Giorgio Armani were a hangover from the late-’80s, early-’90s casuals. There was that big crossover.

But also, there were a lot of people who didn’t give a shit about it. I think more men give a shit about dressing well now than they did then. A lot of geezers would just put a YSL shirt and some jeans on. It was awful. But that was just the way it was for a lot of fellas. It’s quite nice to see that blokes make more of an effort now.

Oh, yeah. They love getting dolled up now.

Style has always been important, definitely. But in these pictures, I did veer towards different subcultural moments to emphasise that point. I’d go and photograph the rock scene in Camden, and the guys and girls were authentic rockabilly. Or I’d go to Club Metro on Oxford Street, which was a nu-metal hang out with guys in huge black jeans and piercings.

I wanted to capture all those different elements of British subcultures, as well as something that was probably a little bit more hip or mainstream as well. I’d go to clubs in Clapham and photograph very, very working-class people that were just cutting loose at the weekend, because that all made sense to me. I was from that.

Before I let you go, why did you go with the title While You Were Sleeping?

Well, this collection of pictures has been in an archive for a very long time, along with lots of other pictures. During lockdown, I was with my son and we were trying to rescue these hard drives that were starting to deteriorate and we salvaged these digital hard drives.

My son, Kuba, started laughing at this section of images from that era, ’98 – 2000s, saying: “I was born in ’98. Where the hell was I?” I said: “You were sleeping.” And so we put the photos in a big folder and titled it, “while you were sleeping”.

Lovely stuff. Cheers, Ewen!

Thanks, TJ!

Ewen Spencer’s While You Were Sleeping is published by Damiani and is available to purchase at damianieditore.com for £45