Behind the rise in fungi fashion lies a psychedelic revolution

Gucci, Fiorucci, Stüssy and Marc Jacobs’ Heaven all helped dub 2020 the year of the mushroom. But here’s why the roots of mycelium mania run a little deeper, well into the new year and, no doubt, the rest of the decade.

Culture

Words: Leah Dolan

How do you make a trend these days? Stick it on Bella Hadid. Let’s take the humble mushroom, the wonky red and white studded toadstool cropping up in fairytale books the world over. Over the past few months, Hadid’s wardrobe has become a shrine to the woodland wights, appearing on bags, trousers, jewellery and even sprouting from the cuticle of her French manicure.

But it’s not just a case of model behaviour. Shroom-inspired pieces have sprung up across fashion houses everywhere, like JW Anderson’s toadstool-printed T‑shirt and Fiorucci’s mushroom phone case, shirt dress and fungi-inspired hoodie. Stüssy nearly sold out most of its spore-ish SS20 collection in a matter of days, while LA artist Alake Shilling has been painting giant gelatinous frogs and neon mushrooms for Marc Jacob’s Heaven, and Gucci’s 2020 collection even includes fungi bum bags for kids.

The appeal of the mycelium hasn’t gone unnoticed in the beauty industry, either. Coveteur, Stylist, Bustle and Dazed have all named fungi as skincare’s hottest new ingredient in the last couple of years. The trend has even made its mark on home decor, like Supreme’s recent FLOS Bellhop Lamp drop, with Google searches for “mushroom lamp” up 110 per cent last year, too.

But, over the years, how did a nearly 100 million-year-old organism become so timely, worming its way into 2021?

“The zeitgeist has totally caught up with what I think artists and designers were looking at anyway,” says Francesca Gavin, curator of the Somerset House exhibition, Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi. Eighteen months in the making and swinging its doors open in January 2020, it was a big hit despite coronavirus forcing the show to close early, though it did later reopen its doors in July for a few months. “We were having 2,000 people a day coming before lockdown,” she tells THE FACE, “which was wild for a small three-room exhibition.”

Marc Jacobs’ Heaven

Stüssy SS20

Supreme

JW Anderson SS20

Fiorucci

We’re scouring the forest floor because of a renewed interest in being outside in the first place, according to Gavin. “I think it’s really resonating [at the moment] because of climate change and a real desire to connect with nature.” This was also a driving force behind the exhibition – an opportunity to draw attention to how critical the environment is to our survival. “Mushrooms are this kind of beautiful, strange, really accessible, even childish way of tapping into our relationship with nature,” Gavin adds. “That’s the thing with mushrooms, they can be metaphors for whatever you’re interested in.”

In a post-lockdown world, our bond with the great outdoors has never been stronger. Last year, the People and Nature Survey for England found that almost half of the British population said they were spending more time out in green spaces than before the pandemic hit. But the metaphor stretches beyond nature into something undeniably human.

“Mushrooms are one of the beautiful mysteries of the natural world,” says Harald Brekke, director of the trend forecasting agency Kjaer Global. “Part of being human is to anticipate what’s coming next. But to some extent, there must also be a factor of the unknown.”

Data collected by the Home Office showed that in 2019 magic mushroom usage doubled in those aged between 16 and 24. Over in the US, Oregon became the first state to legalise psilocybin, the active ingredient in shrooms, this November. It was an affirmation of the decision made by cities Denver and Oakland to legalise and regulate access to the drug in 2019. Washington, DC also passed a measure this past November that aims to limit the prosecution of those in possession of psychedelics.

Joe*, who is 23, first started experimenting with magic mushrooms in 2014. Despite usually saving his trips for summer, he says he’s been drawn to eating more this winter. “I’ve definitely been taking more shrooms over lockdown,” he tells THE FACE. “I usually combine them with weed and very occasionally other psychedelics, like 2‑CB, LSD or DMT.”

When the wrath of Coronavirus meant cancelling public events and separating physical communities, the pace of life inevitably slowed. With no external social outlet, we all turned inwards. Gavin thinks that this enforced self-reflection brought psychedelics to a new generation. “It’s not about clubbing,” she says. “It’s more about what’s going on in [your] head.”

-

THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM! THE SHROOM BOOM!

Brekke, who has helped predict the future for brands like IKEA, Nike, adidas and Virgin Media, agrees this psychedelic renaissance could be in part due to a societal search for meaning. For him, it’s closely connected to the ever-growing wellness movement, an industry that’s now worth £3 trillion. Brekke believes books like the 2018 New York Times bestseller How to Change your Mind by Michael Pollan have been instrumental in the absorption of shrooms into the wellness trend.

Last year, Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle brand Goop sent staffers to a Jamaican mushroom retreat, where therapeutic psilocybin packages range anywhere from $1,700 for a weekend to $10,500 per week. “[Pollan’s book] was very influential,” Brekke tells THE FACE, “because it showed how the idea of psychedelics was connected to something completely different, [in terms of] what psychedelic drugs can do for a person under controlled use in psychiatry or mental health.”

Other parts of the world have been quicker to catch onto the mind-manifesting powers of mycelia. Psilocybin mushrooms have long been used in spiritual practices and cultural rituals throughout Central America. They were nicknamed “the flesh of the gods” by Spanish friars who, in as early as the fifteenth century, recorded the metaphoric trips and visions of those who ate them. Terence McKenna, an American ethnobotanist, even believed magic mushrooms were the original tree of knowledge, kickstarting the creation of art, religion and basically our entire cultural evolution 70,000 years ago.

But it wasn’t until 1957, after Life magazine published the photo-essay Seeking the Magic Mushroom by New York banker and rookie mycologist Robert Gordon Wasson, that shrooms really came to the fore in the west. Wasson had visited Oaxaca, Mexico, where he was invited to a mushroom ceremony by María Sabina, a local healer and shaman. His “soul-shattering” experience was read by millions and captivated a community of American academics already investigating the therapeutic benefits of LSD.

Things moved quickly after that. By 1960, then-professor Timothy Leary had created the Harvard Psilocybin Project and enlisted the psychedelic insight of beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg. A few years later, Leary appeared at an event called the “Human Be-In” – the biggest counterculture event of the century, held in San Francisco and attended by tens of thousands.

It didn’t take long for the buzz to spread to the UK. Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger and John Lennon all went to see Sabina in search of their own transformative experience. But for the average Brit, psilocybin mushrooms weren’t popular until the 1970s. They came into their own after the criminalisation of LSD in 1966, when many discovered mushrooms could be used as its legal alternative.

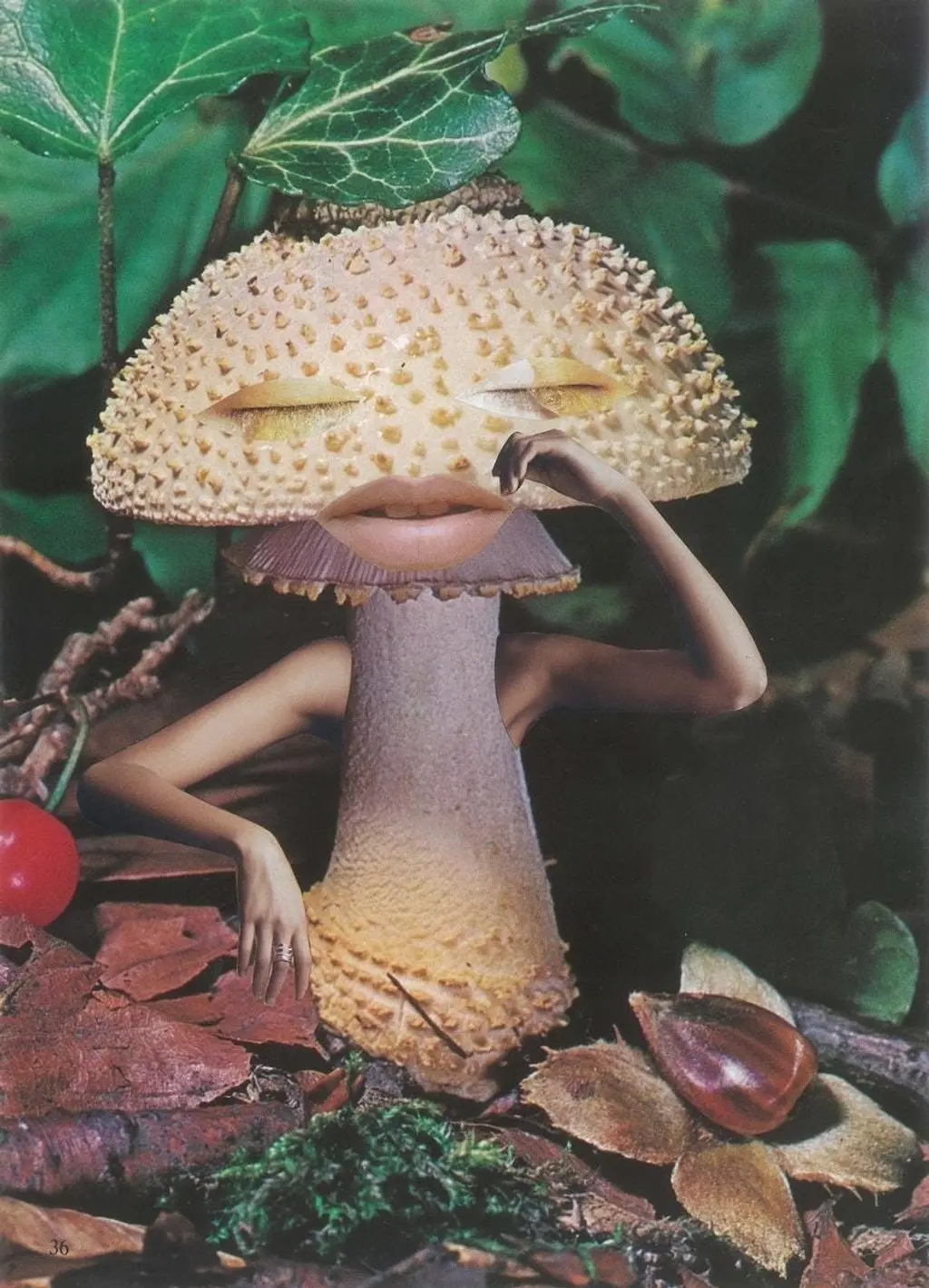

Mindful Mushroom by Seana Gavin, from the exhibition, Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi, shown at Somerset House last year

Artwork from the exhibition, Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi, shown at Somerset House last year

“The things people ingest that get you out of your head are always connected in some way to politics and society at that time,” says Gavin. “The bleak economic situation and rocky political landscape of the ’60s and ’70s proved fertile ground for a burgeoning interest in psychedelics and the escapism they promised. Today, the appeal of shrooms and their otherworldliness have come back around as we try to muddle through some of the same challenges,” she says, referring to the politics, pandemic and protests of the past year.

Amidst the current chaos, Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life explores psilocybin’s use of escapism. It works by shutting down something in the brain called the default mode network (DMN). The DMN, Sheldrake writes, is like a schoolteacher organising the chaos of the human brain. When magic mushrooms tell the DMN to turn itself off, the result is an unconstrained, limitless style of cognition. There’s no nagging teacher barking strict social norms – it all becomes playtime, even if only momentarily.

“Psilocybin appears to take effect not by pushing a set of biochemical buttons, but by opening patients’ minds to new ways of thinking about their lives and behaviours.” Sheldrake says in his book: “By softening the categories that organise human experience, psilocybin and other psychedelics are able to open up new cognitive possibilities.” In their very nature, mushrooms are a form of protest.

“I think we truly want to readdress our relationship to the world and our relationships with each other,” Gavin tells THE FACE. “Politically, the idea of living together is really important right now, as opposed to this increasing difference that creates racism and hatred. It makes sense to me that people are looking for better ways of living – an alternative, utopian idea of the future, and so are being drawn towards ingesting things that expand on that way of approaching life.”

Drugs are always, in some way or another, about escaping. What they release you from, however, depends on what decade you’re living in. As we go through another political awakening, it’s not surprising to see so many embrace a high marked by lucidity and visualisation.

This year felt like an ending for a lot of things: public spaces, crowds, physical touch, live music, the dance floor. But it’s more likely to be the beginning of a new phase. As more people take an interest in mushrooms and more capital is poured into research (the collective shares of Compass Pathways, a UK-based pharmaceutical company who patented a synthetic version of psilocybin to treat severe depression, has now reached $1 billion), this could be just the start of our obsession.

“I think it might lead to even more interesting aesthetics and ideas,” Gavin says, “beyond just the mushroom-wear and fast fashion T‑shirts.”

* Name has been changed