Sunil Gupta: photographing India’s queer scene over 50 years

Sunil Gupta, Manpreet

The New Delhi-born photographer has documented LGBTQ+ life for over 50 years in India, the US and here in the UK. Now, The Photographer’s Gallery is commemorating his body of work with a retrospective, from the streets of New York to various parks in Delhi.

Culture

Words: Lauren Cochrane

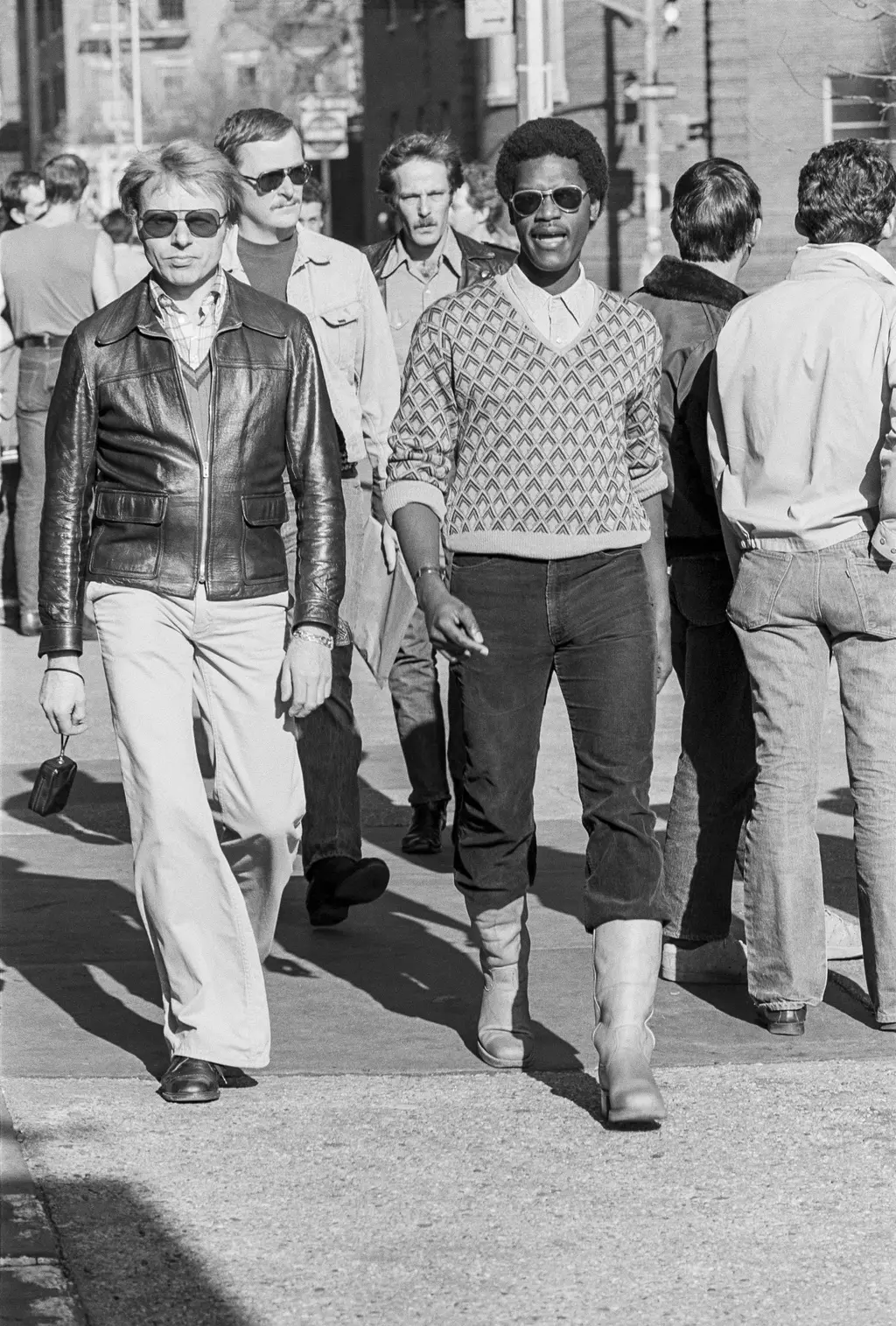

Photographer Sunil Gupta has been documenting LGBTQ+ life for 50 years – from Christopher Street in New York in the 1970s, to parks in his Delhi hometown in the ’80s. Throughout his career, Gupta has gone about answering one question: what does it mean to be a gay Indian man?

This journey of discovery will soon be seen at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, where a long-overdue retrospective, From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta. A Restrospective, opens tomorrow. Here, Gupta talks about his work, the importance of putting different stories in the art history narrative and how he could have ended up a stockbroker.

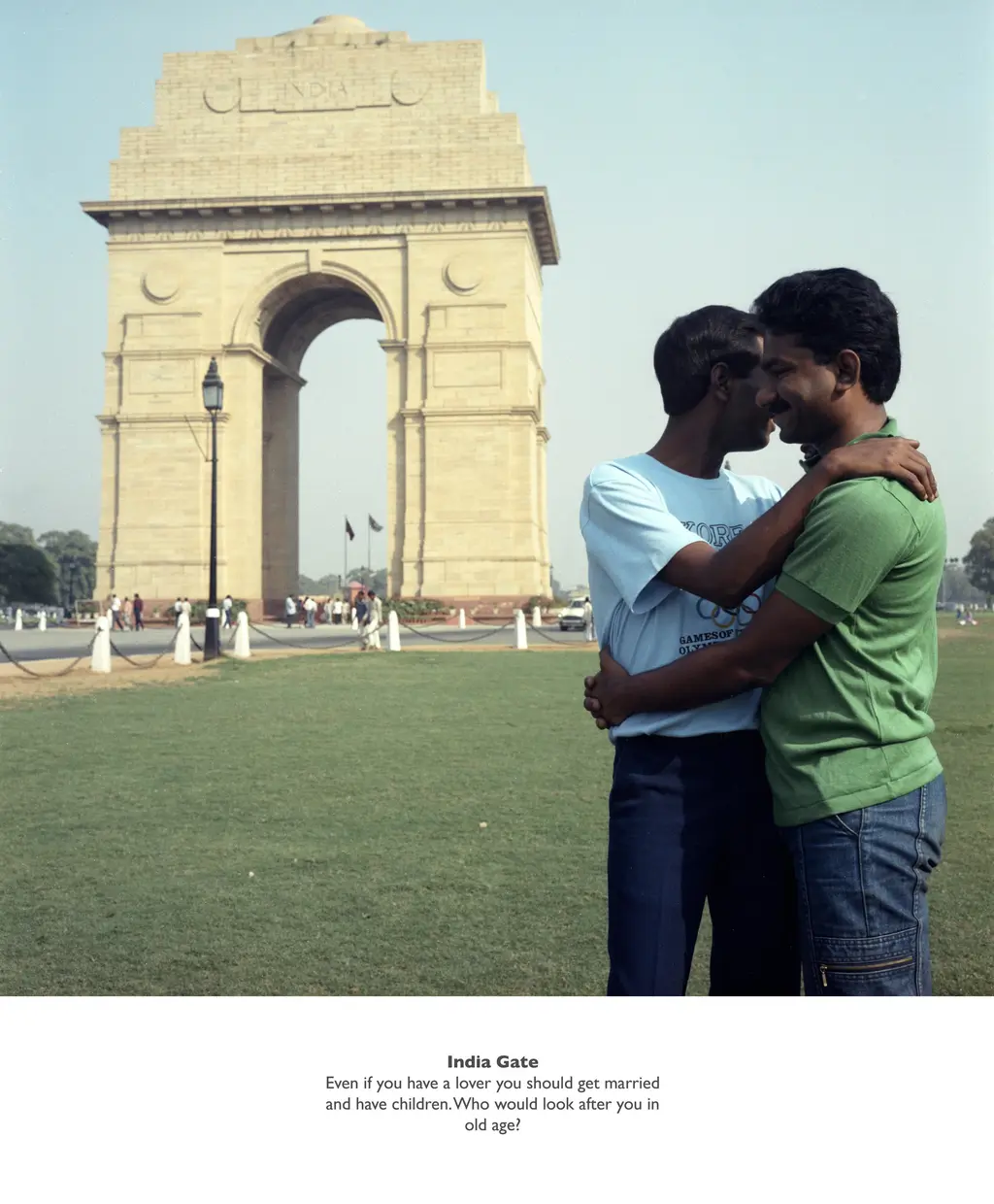

India Gate

Untitled #22

Untitled #7

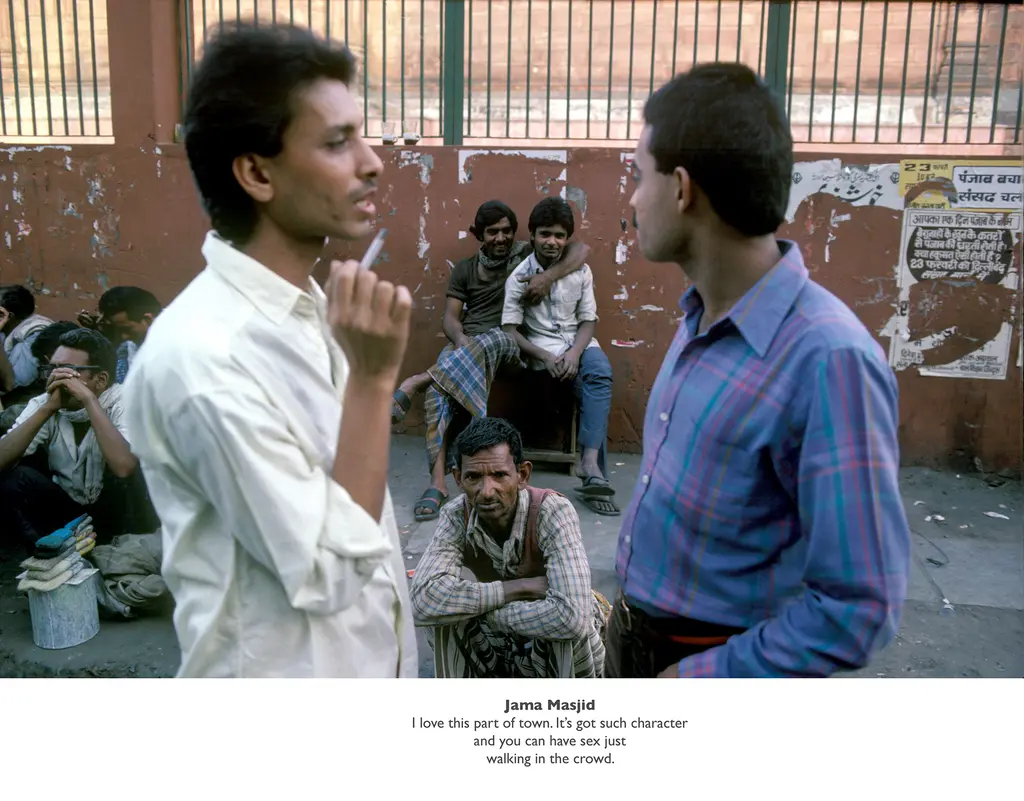

Jama Masjid

Shroud

Sun City #9

How does it feel to have a retrospective?

I haven’t seen it [all together] yet so I’m looking forward to it. I thought “I’m not done yet, it’s too early, I have more things to do.” It seems like it should happen after you have finished…

How did you get into photography in the first place?

My gay liberation student outfit had a newspaper that needed pictures, so I made the pictures. I was in a liberal arts college, so I had a very gay academic education. We would read studies on “why gay men go to public toilets”. We thought cruising was very capitalistic and very one to one, which means the community was divided because everyone is in competition trying to get laid.

You also studied at New York’s New School with Lisette Model, who taught Larry Fink and Diane Arbus. What was she like?

If she didn’t like something she’d say “darling, that’s shit, go and try again”. If she liked something she’d say “wonderful, we must go and visit MoMA”. I think she liked me – she took an interest in what was going to happen to me. I was in New York to do a finance degree, and go to Wall Street.

What changed your mind?

She did. She said I must do photography and not do stock markets. I couldn’t see how that kind of thing was going to earn me a living and I was a little bit right about that. I’ve often thought in my very lean moments that I could have been a partner in some whizzy accounting firm with a swimming pool and a chalet somewhere, instead of stuck in one and a half rooms in Stockwell.

Do you think you would have been happy?

I would have shopped a lot and then got bored…

The Christopher Street (1976) pictures were your first series as a practising artist and they were published in a book in 2018. Why do you think the images have become a reference for a new generation?

They have this new meaning, the moment of something flowering in a positive way… We thought “we’re not going to have any kids, we’re going to have sex with everybody and be very promiscuous and frighten everyone” and that’s kind of what we were doing. Lo and behold, AIDS came along. Those were days of hedonism and freedom.

It’s bittersweet to look at these images now…

Yeah, because you know they are walking into a Holocaust – a lot of them are not going to make it.

The title of The Photographers’ Gallery show is the same as your 1999 work about living with HIV. Can you tell me a bit about that?

It was a commission from Autograph [the organisation dedicated to photographers of colour]. I had been diagnosed four years earlier but I had decided to not make anything about my HIV status. I felt I had accumulated too much baggage, anyway. I was gay and then I was Indian and if I added that I felt I had become an island. But around the time of the opportunity, I wasn’t well. I did it to talk about the illness and make it public, but also to try and feel better.

Do you see your work as political or do the images exist outside of politics?

I see it as being politically motivated. I became aware through art school that this whole thing called art history is our context and my story is not in it. So I thought the challenge is “how do you put the gay Indian thing into it?” I’m very glad that [my work] is in collections now, some in the Tate, some in MoMA. It was a very postmodern decade I grew up in, everyone was talking about the recent past, but I basically had no past. When Andy Warhol does Marilyn Monroe, it works because we know who Marilyn Monroe is, but if I did it with a similar character from my very specific gay Indian subculture, and there are such people – female movie stars who move gay men to tears – no one in my audience would recognise anything about it. It would kind of be meaningless.

What do you think of platforms like Instagram?

I was slow to get on it but now you can’t take me off it – but I don’t have a camera fetish. Like the rest of us, what I have with me all the time is my phone. Phone cameras are so good – you just think about the composition and the colours. The only downside is that people have begun to work with it. Instead of sending an email they will send an Instagram instant message. That’s a bit of a downer, work intruding into play.

From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective opens at The Photographers’ Gallery, London from 9 October – 24 January 2021