How protesting took over a pandemic-riddled world

2020 in review: In a year of lockdown and social distancing, millions have hit the street to stand in solidarity against injustices that pre-existed – and were made worse by – the government mishandling of Covid-19.

Life

Words: Amy Francombe

Photography: Craig Bernard

From an energised rallying call to #EndSARS, to the UK’s largest national student rent strike of all time, and a democracy-defining election in the US, 2020 has been a year of protest.

“Despite coronavirus, the spirit of protesting hasn’t been killed off,” says Richard Young, a senior fellow of Democracy, Conflict and Governance at Carnegie Europe. “If anything it’s added another layer of reasons why citizens should take to the streets.”

Last year, publications such as The New Yorker, The Telegraph and The Financial Times called 2019 the “year of the protest”, citing spontaneous uprisings in every corner of the world: from Hong Kong to Lebanon, and Iraq to Chile.

“When the virus hit, a lot of people thought this would be the end of this wave of protests because the government had made emergency measures that would make protests illegal, or at least very difficult,” Young continues. “For a while this was the case – but the interesting thing is in the aftermath of the initial period of lockdown, we’ve actually seen across the world an even greater disposition to protest arise, fuelled by the pandemic highlighting the flaws that existed in systems for decades, even centuries.”

In Trump’s US, which was at the time experiencing over 6000 Covid-19 related deaths a day, around 20 million Americans took to the streets following the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minnesota Police Department in May. In the UK, more than 210,000 people attended demonstrations over the month of June in solidarity, toppling 17 monuments of people who profited from slavery in the process.

“The pandemic has held a mirror up to so many structures in our society that do nothing but serve the elite class,” Lizal Bila, a 21-year-old student and activist who helped organise Bristol’s Black Lives Matter protests, told The Face earlier this year. “Being a Black person and witnessing the disproportionate deaths of fellow Black people in this country to Covid-19, alongside the virus of systemic racism which has plagued our society for centuries, has been particularly heartbreaking and emotionally exhausting.”

For supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement, which was first established in July 2013 following the acquittal of George Zimmerman following the shooting of Black teen Trayvon Martin 17 months prior, the pandemic wasn’t a barrier to protest – but a catalyst.

In Britain, ONS found that Black people are four times more like to die from Covid-19 than their white counterparts, while in the US data from the Centers for Disease control highlighted that almost one-third of infections nationwide have affected Black people, despite the demographic representing only 13 per cent of the population.

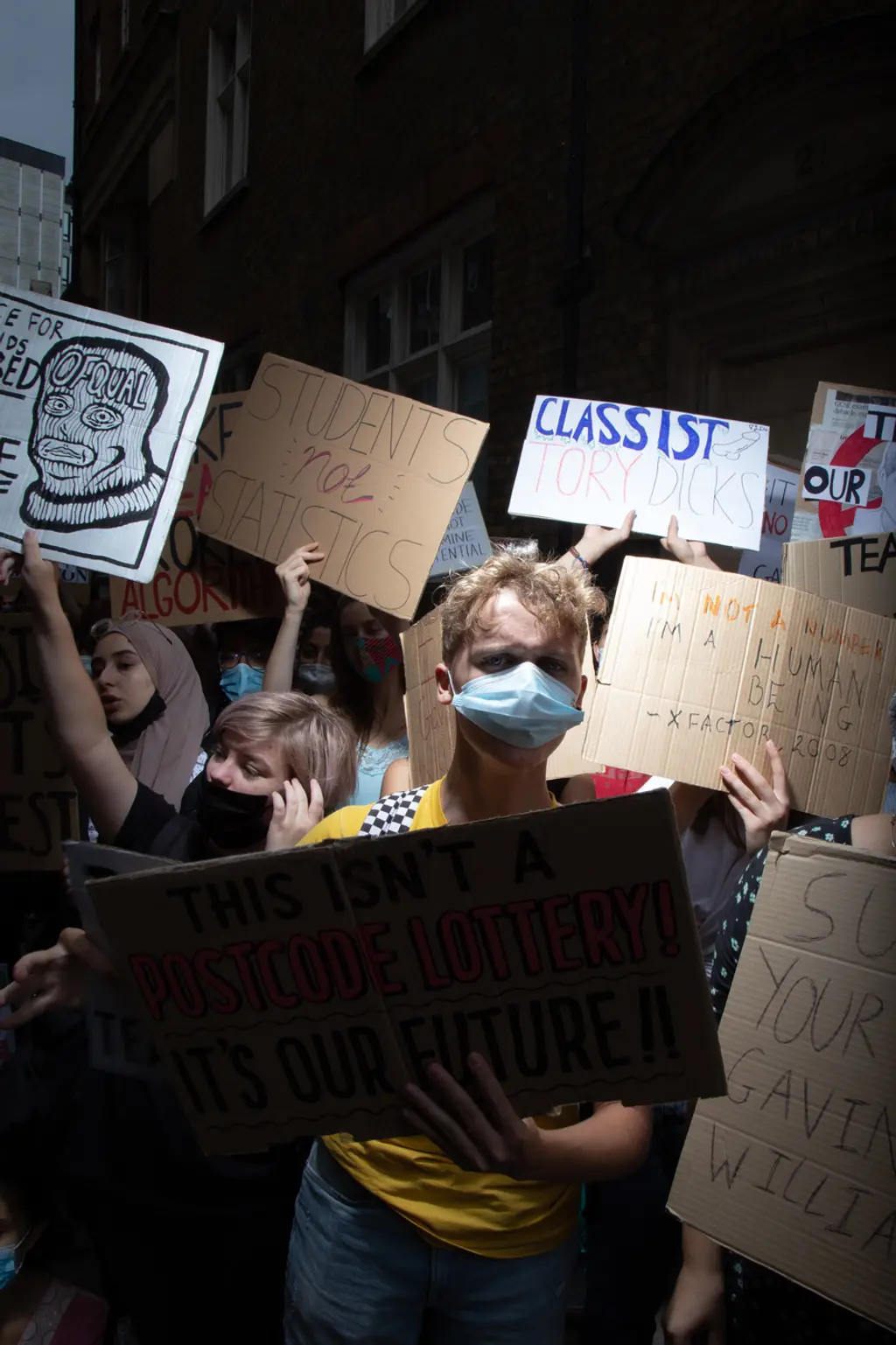

Take the current rent strikes being held by students across the country, too. Freshers – having been actively told to start university and repeatedly assured that it would be safe to move into halls – were swiftly put into campus wide lockdowns in Manchester, Bristol, Glasgow and Newcastle, with all other institutions moving lectures online. Understandably angry at paying over £9,000 a year for sub-par online lectures in box rooms, the students began revolting. First with post-stick plastered protest signs at Manchester Met, then with IRL, pots-and-pans banging protests in Bristol, before ending with a 12-day occupation of Owen’s Park Tower in Manchester.

“We feel like cash cows,” Hannah Phil, a first year drama student at Manchester Met who helped organise the occupation that won a £12m rent rebate from campus authorities, says. “Our safety has blatantly been put at risk in order to help universities stay afloat.”

“The marketisation of education has always been something that students have protested against,” continues Phil. “But the pandemic has shown just how deeply flawed the system is. Covid-19 should be taken seriously, but the government and university’s handling of the virus has left us no choice but to break social distancing.”

Despite the mass swell of IRL protesting this year, the pandemic has meant the tactics, tools and structure of civil resistance have had to change, too.

In June K‑pop fans urged TikTokers to sign up to a Trump rally and not attend, resulting in only 6,200 people turning up to fill Tulsa’s 19,000-capacity BOK Centre. On Twitter, people began matching donations en masse to bail funds in May, with more than 50,000 donating a total of $1.8 million in less than 24 hours to support the Brooklyn Community Bail fund. While on Instagram, social justice slideshows dissecting complex issues and turning them into accessible call to actions dominated feeds, the most notable of which @soyouwanttotalkabout, accumulating 2.1million followers in just five short months.

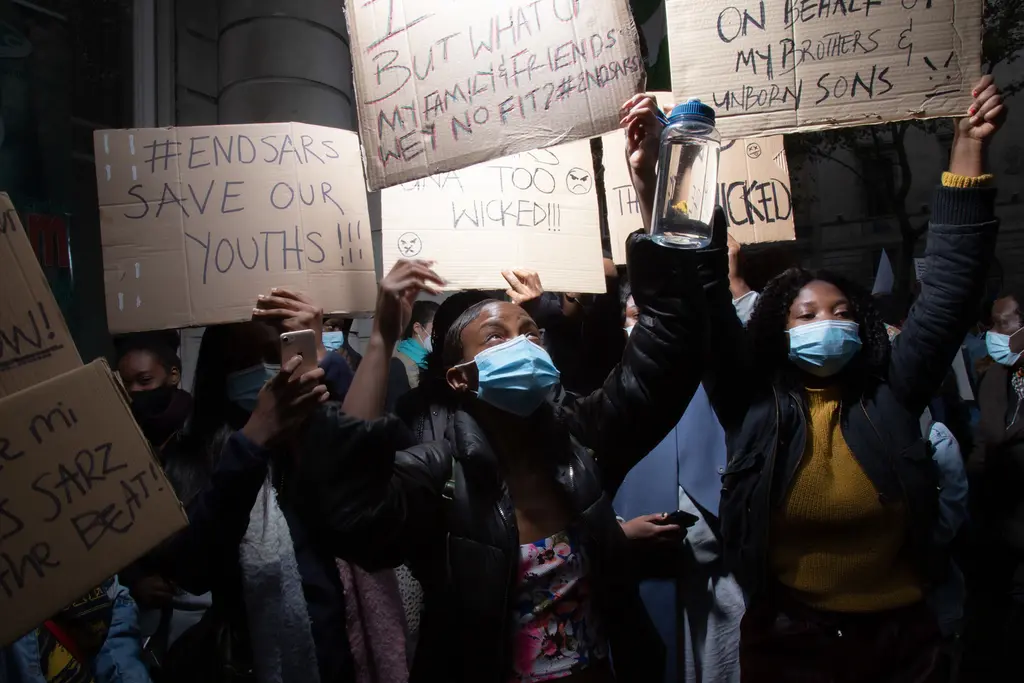

#EndSARS, London Embassy, 11th October 2020

The aurora of discontent seeped into music, too. During the first weeks of BLM, the system-fighting rap anthem Fuck The Police saw a 272% increase in streams. New artists were fast to respond to the global sentiment, too: rapper-slash-activist Dua Saleh dropped their track body cast in response to protests against police brutality; Compton rapper YG surpassed his label by dropping FTP (Fuck The Police) to support BLM; and Killer Mike EL‑P dropped his highly anticipated fourth studio Alub, RTJ4, two before its planned release date in solidarity with the movement.

Moreover, when music wasn’t being released to support such causes, it was getting halted. Afropop artist Davido postponed his star-studded album A Better Time in October to throw himself into #EndSARS – the movement to disband Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad. Meanwhile his single FEM, released back in September, found itself used as a protest anthem for Nigerian youths to chant while fighting against their country’s corrupt police unit.

“My speculation is that we’re going to see more protests, not less. It’s the calm before the storm,” Young says when asked about how he sees the current anti-establishment sentiments will continue into the new year. “The really difficult politics will come in the post-virus world when we have to decide who pays for the costs of the virus.”

While in 2020 the world was told to stay at home, causes just as affecting as Covid-19 have drawn millions to the streets. Whether we like it or not, the virus won’t expire come 31st December, and the floodlight it’s thrown on centuries-old, systemically-embedded injustices will continue to push the surge of protests for years to come.