The economy of guest rap features

Guest verses can be key to the promotion and quality of a hip-hop album. In today’s world of streaming and relentless content, how much do they cost and what’s the payoff?

Music

Words: Kathy Iandoli

In the world of hip-hop, like most industries, it’s all about who you know. But with rap music, however, you need more than social media posts to show off your alliances and cosigns. Rather, it’s proving that kinship on wax. From Busta Rhymes proving his rowdy star appeal on Scenario by a Tribe Called Quest back in ’92, to Nicki Minaj launching her career after bodying the male rap heavyweights on Kanye West’s Monster, to Drake boosting Travis Scott’s Sicko Mode into one of last year’s biggest anthems, the story of hip-hop is paved with show-stealing guest verses, and every rapper dreams of delivering one.

We felt the magnitude of a strategically successful feature recently when Nicki Minaj jumped on Megan Thee Stallion’s single Hot Girl Summer with Ty Dolla $ign. For years, Nicki has come under scrutiny for her lack of collaborations or even cosigns of newer female rap acts. Showing up on Megan’s song was monumental; Thee Stallion has been pegged as the new hip-hop “it” girl with good reason, and now Nicki – arguably the reigning Queen of Rap for a decade – was nodding in agreement. Cosigns of rising talent from megastars run deeply. When Jay‑Z hopped on J. Cole’s Mr. Nice Watch back in 2011, the world rejoiced as the Roc Nation freshman got his coveted verse from the enterprise’s owner, and it set the tone for what would follow for Cole.

When it comes to a guest feature, there’s much more to it than holing up in the studio and cutting verses together or even mailing one part in to combine with another. And although some of the greatest guest features are the result of creative kinship and spontaneity in the studio, there’s usually an infrastructure in place, riddled with label politics and bottom lines that can often determine the successful fate of that feature. Hell, it can be the barrier to the feature even happening in the first place.

The game of guest features is a complicated one, so let’s dive in.

“The hardest times are when it is a collaborative label effort, because everyone wants to get a piece of the pie.”

Chanel McFadzean, PR and Brand Strategist

THE ANATOMY OF A FEATURE

From an industry perspective, rappers can be seen as players who are at various levels in their careers. With each level, the stakes change. Essentially, the first step is getting all parties to agree to work together. Often, it’s merely a pool of artists cutting tracks with their peers.

Take the Soundcloud rap phenomenon, where artists who all came up in the Soundcloud world will frequently collaborate with one another. Here, it’s a matter of friends helping out friends, often for little to no money at all. The goal is recognition and camaraderie, so really it’s just a party on record. This can be said for most newer hip-hop artists who work with other artists of their calibre, where the product will more than likely appear on a mixtape without label intervention (if the artist/artists are signed).

But when an artist’s fame grows, things change. Bigger names require a different protocol for the song to happen.

Chanel McFadzean is the Public Relations and Brand Strategist at the Legion Group. Her clients range from rap veteran Jim Jones to New York’s premier hip-hop radio station, Hot 97. She cites an example of a simple “artist to artist” scenario that happened earlier this year, as Jim Jones had a Rick Ross feature on his seventh studio album El Capo on the track State Of The Union. Here, it came down to Jones contacting Ross directly.

“Every artist’s camp is different,” McFadzean says. “Sometimes if there is a newer artist that your artist wants to collaborate with, I would then reach out directly to that person’s publicist and figure out who handles what. They might only work with one producer, so it might be that producer’s job to coordinate those features or it might be management only.”

When artists are signed, the outcome changes as well. “It might be a label decision,” McFadzean explains. “Sometimes… the hardest times are when it is a collaborative effort, because everyone wants to get a piece of the pie, meaning this is a paid partnership and not for a random mixtape someone wants for just a quick collab.” Multiple labels can cause a lot of red tape, particularly if one label is on board to have their artist on the track yet the other isn’t. Or, if there is a higher profile independent artist who wants to work with a newer signed act, but the label may be on the fence as to how the collaboration will affect their new artist’s brand.

Read next: How do young Muslims feel when rappers reference Islam? Hip-hop artists have been celebrating the religion in their songs for decades. But recent controversies have got Muslims wondering where the line needs to be drawn.

DaBaby and Chance The Rapper performing in NYC. Photography by: Debra L Rothenberg via WireImage

While this might sound coldly strategic, the transaction isn’t always financial. “A lot of times [the artists] won’t even pay each other,” says Entertainment Attorney and Music Law Professor Cassandra Spangler. “Equal level artists will do what they call a ‘swap’ so that means Lil Wayne does a feature for Drake and then Drake agrees that at some point in the future he’ll do a feature on Lil Wayne’s album. It’s in the paperwork. Usually, they’ll get some of the publishing, but no fee and no royalties.”

Speaking of compensation, how much do features actually cost? Both Spangler and McFadzean echo that the lower end for newer artists hover between the $3,000 to $5,000 range, though that grows with an artist’s celebrity status, going as high as $25,000 or even higher. On the aforementioned Monster, Nicki made a slick comment that she charged “50k for a verse, no album out,” which has apparently escalated since then, according to her claim that she “just got 250 thousand dollars for a verse” in 2014. DaBaby, who’s enjoyed a sudden rise to fame in 2019, has said that he charges $25K for a verse. The numbers are growing.

“I have heard cases where very famous artists will take a bag of $150k in cash.”

Paul Cantor, author and industry veteran

DAVID VS. GOLIATH

“The way people perceive you is based on who you’re standing next to,” says author and music industry veteran Paul Cantor. “An artist can use guest verses to build their profile, so if you’re on a song with somebody who is deemed culturally important, you can get people to pay attention to you.” He references Nas’s breakout verse on Main Source’s 1991 track Live At The Barbeque as an example of what happens when a newbie is in the right place at the right time. Nas blew away the veteran competition as merely a teenager, with his verse being the gateway drug to what would become his glow up introduction to hip-hop with his game-changing debut Illmatic in 1994.

It sounds simple enough, but there are risks when a newer artist is footing the bill. Social media accounts are rarely managed by the big names themselves, so that money could be sent out into the world and landing anywhere but in the appropriate person’s pockets.

“Artists sometimes don’t realise the importance of having a contract in check when it comes to features,” Spangler explains. “Normally it’s usually an unknown artist who is paying a well-known artist for a feature. With social media, there are a lot of people who reach out to artists directly for a feature and you have to get approval from an artist, but separately you have to get approval from the label.” A simple agreement with those stipulations can easily prevent a disaster. “What you want is a contract that says [the bigger artist] is agreeing to do this feature but [the newer artist] must get approval from the label and it’s up to them to do it.” Bigger artists will gladly pocket the cash, unbeknownst to them that they can’t hop on the track without their label’s OK. “They can get themselves in bad situations where someone pays for a feature and the label may say no,” Spangler continues, “but they already took the money and then it creates this whole mess.”

An incident happened earlier in the year, where rapper Yo Gotti was paid $20,000 to appear on a track with rising artist Young Fletcher, yet the song never materialised. Instead, Gotti dropped a song strikingly similar, attempted to bypass management and sign Fletcher to a recording contract for $150,000. The result was a North Carolina court ruling in Young Fletcher’s favour for punitive damages totalling $6.6 million. That’s a rare instance since newer artists don’t always wind up the victor, evidenced by cases where an artist empties their pockets and the track goes nowhere.

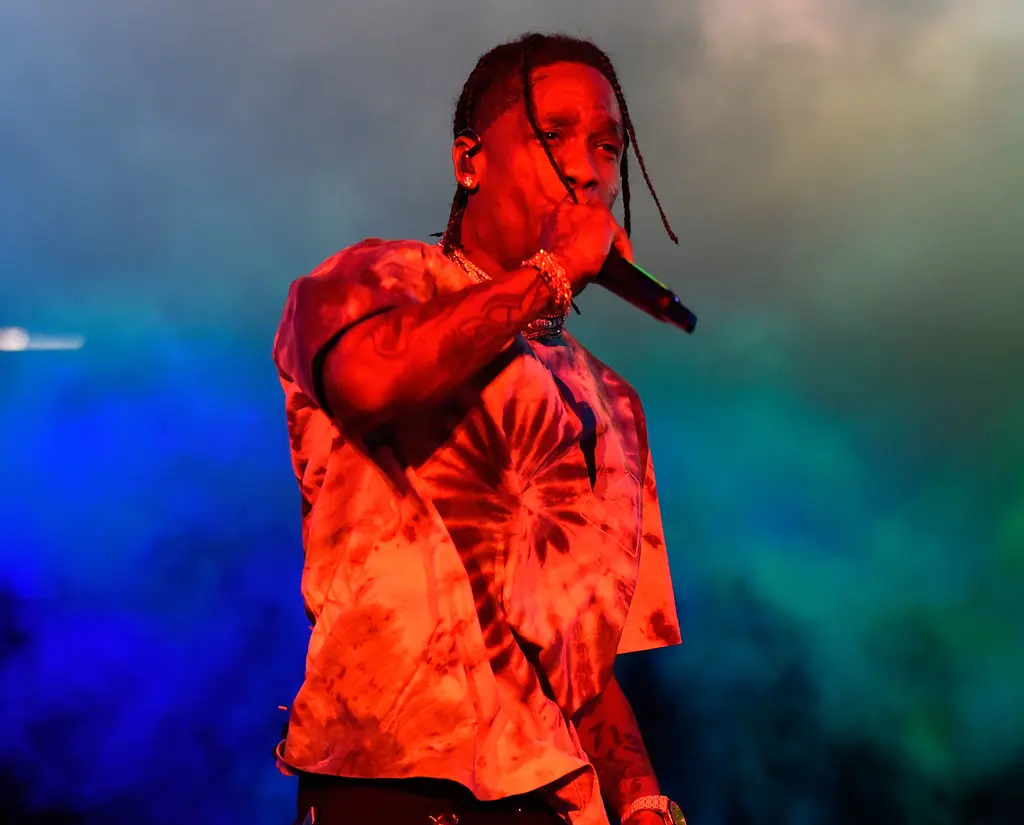

Travis Scott at Made in America 2019 in Philadelphia. Photography by: Arik McArthur via WireImage

Travis Scott and Drake backstage at 2019 GRAMMY Awards in LA. Photography by: Rich Fury via Getty Images for The Recording Academy

“A lot of times people will spend the money on buying the feature, but then have no money left to market the record,” says Mike Trampe, Marketing and Social Media Director for BeatStars. “They think the feature is going to do the marketing for them, and that’s a big mistake.” How much is a new artist even willing to fork over for a life-changing feature? “I have heard cases where very famous artists will take a bag of $150k in cash,” Cantor adds. “They’ll show up to a location with a green screen, do the verse, and shoot a video.” Again, it’s up to the newer artist to market it. Further, the question of credit comes into play, as higher-profile artists may have specific rules regarding how their names are listed on the track’s credits.

“It’ll typically say in the agreement that the credits will feature the artist’s name,” says Spangler. “That’s something that also gets tricky because they’ll argue sometimes about whose name to list first in the instance of multiple features.”

Streams can also be affected. “It depends on how you report the track to Spotify as far as whether it’s going to show up on the featured artist’s page.” Eliminating that can reduce the track’s visibility which, again, falls on the newer artist’s shoulders to market the track. We saw this very early on in 1999, where a then-unknown Eve had a verse on The Roots’ breakout hit You Got Me, yet only Erykah Badu was listed as a guest feature for her hook. Travis Scott wasn’t listed as a guest on Rihanna’s Anti song Woo, yet his voice is present throughout the track. It’s now not uncommon for major artists to not list the guest rappers on the album tracklisting for streaming platforms (see Travis Scott’s Astroworld, or Chance The Rapper’s The Big Day – which initially didn’t credit guest rappers on the tracklisting, but has been amended so that it now does). The bigger the artist, the less of a need they have to mention a newer artist as a feature, though in reverse it means everything.

“Content is more important than the feature now”

Mike Trampe

Cardi B and Lil Nas X performing in New Jersey. Photography by: Johnny Nunez. via WireImage

THE RISK AND THE REWARD

It isn’t always a tale of some young buck peddling their tracks in earnest and spending heavy coins to collaborate with the artist of their dreams. Sometimes the bigger artist is diving into the unknown. “The flip side is that you do so many verses that a verse from you is no longer special,” Cantor expresses. But money talks.

“The potential to make money is the decision you have to make as an artist,” McFadzean says. “There’s a fine line to diluting your brand, though.” A series of questions must be asked by the party approached for a feature. “Does it fit the brand or is money talking?” McFadzean continues. “Maybe they’re offering a ridiculous amount of money, like, ‘Okay let’s give them something so everybody can eat.’ These are realistic conversations that you have to decide on.” McFadzean adds that a legacy artist can easily make closely $50,000 a month in features alone, though overexposure will dim the excitement for an artist’s audience.

In the contemporary music industry, content is king, so a song’s mileage is often determined by how much buzz you can generate from it. “Content is more important than the feature now,” Trampe argues. “What are you going to do after you land that feature?”

Megan Thee Stallion onstage in LA. Photography by: Scott Dudelson via Getty Images

Are we really led to believe that Megan Thee Stallion and Nicki Minaj just spontaneously appeared together on Instagram Live and it led to Hot Girl Summer? Or was it a ploy to pre-promote the track, which would later lead to further content, as Nicki dedicated time on Queen Radio to discuss the track, the haters and the hype surrounding it? Either way, it’s content, and it’s needed to keep the momentum going after the track has been recorded and released. “It’s all about dragging out that content as long as possible,” echoes McFadzean, mentioning how press teams will work to keep the news cycle focused on that one song.

There’s something fantastical about collaborations and what they mean to the fabric of hip-hop. We turn to the glory days of hearing Jay‑Z and the Notorious B.I.G. trade bars on Brooklyn’s Finest, all nine members of the Wu-Tang Clan crammed in RZA’s studio, or Lil’ Kim dominating her verse on Mobb Deep’s Quiet Storm (Remix). It’s more fun to think about the magic of the music and the creative chemistry, rather than the checks and balances that might have been in place to make it happen. In the spirit of loving music, let’s keep it that way.

Read this next: The proud tradition of alter egos in female rap