It’s time breast cancer awareness got more inclusive

As CoppaFeel! and LGBTQ+ cancer charity Live Through This work to make breast cancer awareness resources more trans and non-binary-friendly, THE FACE meets a trans survivor to hear why their work is so vital.

Society

Words: Alim Kheraj

Rob learned that he had breast cancer after he had his top surgery, the procedure that alters the appearance of a trans person’s chest. “I’d had to go down to Plymouth to get that, which is about 200 miles from where I’m living,” he recalls. “I had my top surgery; it was very successful and everything went well. Then about three weeks after I’d had the operation, I got a phone call from the surgeon who had done my procedure saying that, within the tissue that they had sent for biopsy, they had found a small, pea-sized cancer.”

Rob, who is nearly 56 and began his transition in 2015, was understandably in shock. Fast-tracked by his GP to a breast care services unit at a local hospital, he was told that the mass was an oestrogen-receptor-positive cancer. “The consultant said to me, ‘Put it this way, Rob: your transitioning has saved you twice. You’ve come for your top surgery and we’ve found the cancer. But because it was an oestrogen-receptive cancer and you’ve been on testosterone for four years, it’s starved it so it didn’t grow as big as it could have done.’”

Thankfully, Rob’s surgeon explained that the cancer had been within surgical margins, meaning that it hadn’t spread outside of the biopsy tissue. To be cautious, he was admitted to hospital for an axillary clearance, which involved removing all his lymph nodes under the armpit on the side of his body where the cancer was found. He was also put on Tamoxifen, a hormone therapy for breast cancer that blocks the effects of oestrogen in the breast tissue.

Living with cancer is already a difficult thing to deal with and overcome, but Rob also encountered other barriers during his treatment. “In the breast care services unit, they have dedicated breast care nurses who you deal with throughout your treatment,” he explains. “My breast care nurse said, ‘Alright Rob, here’s some information for you. Unfortunately, we have no trans-inclusive or specific information.’ I was having to cherry-pick between information for cisgender females with breast cancer and cisgender males with breast cancer. I was falling in the cracks between the two.”

This wasn’t the only experience where Rob’s needs as a trans person experiencing cancer weren’t truly considered. While he had been on testosterone for four years by the time he was diagnosed with cancer, he was taken off his hormone therapy until he had his treatment pathway organised. “That took seven months,” he says. “I was left in limbo for that period and it didn’t help that we were going through Covid at that time as well. I wasn’t getting any communication from the gender identity clinic, and while the breast care service was doing its best, they had a lot on their plate with the pandemic.”

Essentially, what Rob found was a lack of understanding for his healthcare needs and a lack of communication between himself, the gender identity clinic (GIC), the breast cancer care service and his GP. “That was the kicker,” he adds. “It was almost like I couldn’t find the right questions to ask to get the right answers.”

Anyone familiar with the ins and outs of trans health-care won’t find Rob’s story unique. According to Stonewall’s LGBT in Britain – Health Report, 25 per cent of LGBTQ+ people have said that they’ve experienced a lack of understanding by healthcare staff when it comes to their specific needs. For trans people, 62 per cent said that they had experienced a lack of understanding of their issues; 41 per cent had experienced this within the last year.

“In my view, a lot of trans related health and messaging is focused on transition and sexual health,” says Stewart O’Callaghan, who is non-binary and queer, and has their own experience living with cancer. “I was sick of not seeing enough resources [for LGBTQ+ people]. The thing that was clear to me from seeing different bespoke pieces of trans information was that a lot of trans cancer information is just about screening eligibility. But there are some factors when it comes to screening, like self-maintenance and the way you support your own health, that are completely missing for trans people outside of gender medicine and sexual health.”

The lack of support and resources led O’Callaghan to found Live Through This, the UK’s only cancer support and advocacy charity for the LGBTQ+ community. Their work involves not only educating clinicians and healthcare providers about the nuances and intersectional needs of LGBTQ+ people who are experiencing cancer, but also providing meetings for LGBTQ+ people who are going through that experience and creating resource materials.

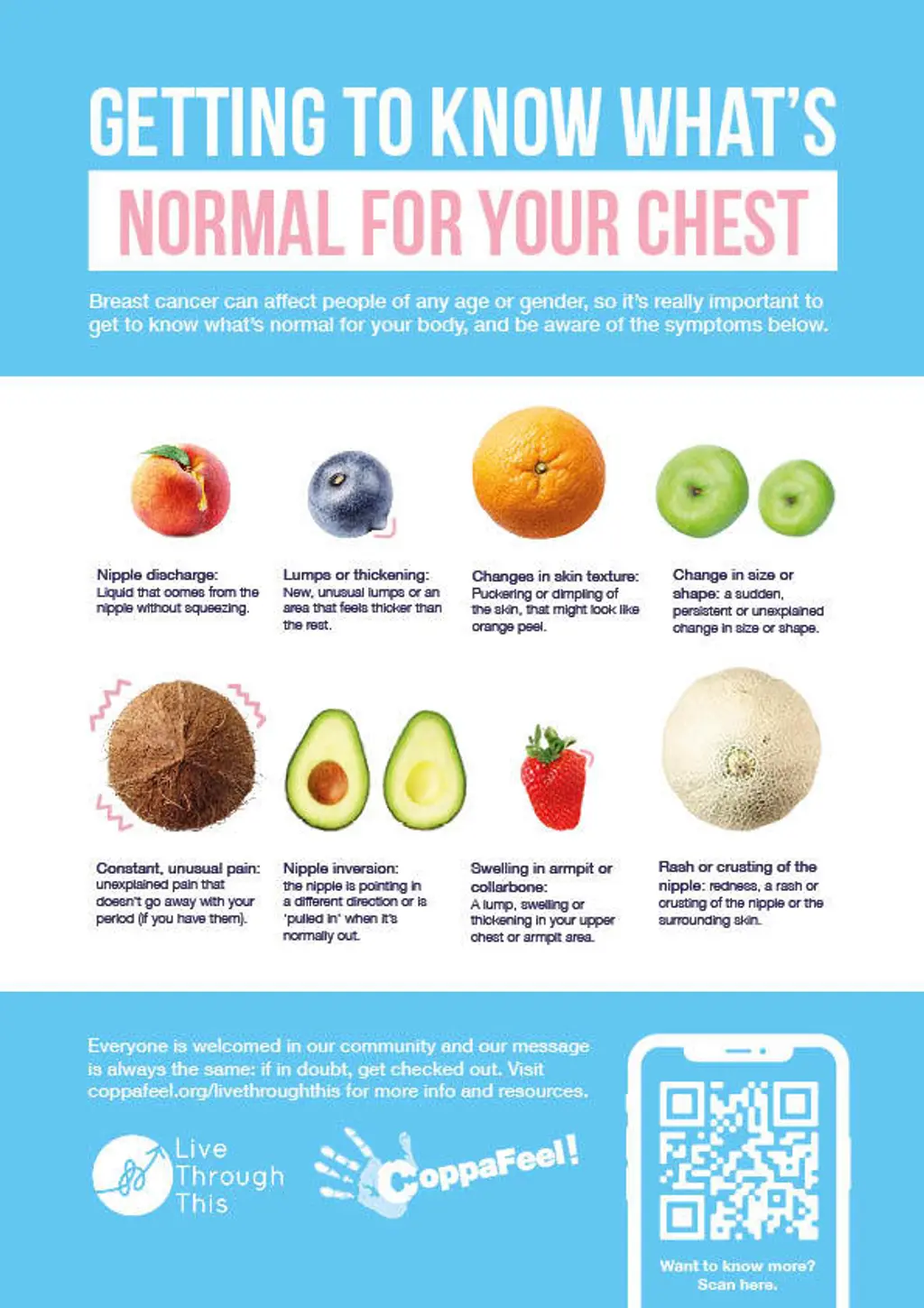

Most recently, Live Through This has collaborated with breast cancer awareness charity CoppaFeel! to create trans and non-binary inclusive chest-checking posters and resources. “Breast cancer can affect people of any age or gender, so it’s really important to get to know what’s normal for your body and understand how it could change if you are transitioning,” says Sinéad Molloy, Head of Marketing at CoppaFeel!.

But as O’Callaghan notes, a lot of breast cancer resources are very cis-centred. “This is the way it has always been, but what happens is people who find certain words dysphoric or triggering are not going to access those resources. And, for example, if you go on to Google and search ‘breast cancer’, it’s all pink. It can be very dysphoric for people.”

To create new and inclusive materials, Live Through This and CoppaFeel! consulted trans and non-binary people through focus groups to identify where the gaps were. They landed on using images of different pieces of fruit as an effective method to present symptoms of breast cancer that weren’t contingent on anatomy.

“What was happening was that sometimes trans people that we were speaking to were feeling that when you show a very typical male chest or female chest to showcase signs of symptoms, not only was it potentially dysphoric, but it also felt like an inferred goal of how a chest should look,” O’Callaghan says. “That’s why we wanted to step away and move into this abstraction, but still find something that could be clinically relevant.”

Dr Alison May Berner

As a result of a lack of time and funding within the NHS, it has fallen on the third sector to generate such resources. This is emblematic of cuts across the board to the health service, but also of the rising demand for gender identity provisions in England. Since 2016 there has been a 40 per cent increase in referrals to GICs, with some people waiting four years for their first appointment.

However, according to both O’Callaghan and Dr Alison May Berner, an oncologist and part-time speciality doctor in gender medicine, there is also a wider problem of a lack of knowledge among healthcare providers when it comes to the specific needs of LGB, trans, non-binary and gender-variant people who may also be experiencing cancer.

Dr Berner suggests this is because of a dearth of education at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, and because the research area is still only slowly growing. But she also highlights the hostile political climate that trans and non-binary people are currently facing. “I think there’s a lack of confidence because clinicians want to be inclusive of trans and non-binary people while not alienating people with less inclusive views,” she says. “I do still think we’re on an upward trajectory towards openness, education and engagement in this area.”

Insufficient knowledge causes a lack of confidence among clinicians. This can lead to all sorts of issues, such as little understanding or awareness of patient experience. There can also be a lack of cultural humility for something that does not fit a white cisgender heteronormative ideal and, as in Rob’s case, an intervention in hormone therapy.

“Sometimes hormones are stopped and started unnecessarily, and even a fear of that can stop trans people from coming forward with health issues,” explains Dr Berner. “There’s paternalism over hormones. Clinicians don’t always realise that, actually, they are a little bit different from normal medications. They’re actually about people’s general wellbeing. This isn’t any old medication. You can’t just say, ‘We’re going to stop that.’ That needs to be a two-way discussion with the patient because that person might rather take a greater risk of cancer than come off that hormone and that is their right.”

Rob

There’s also the concept of the “trans broken arm syndrome”, which O’Callaghan says is a common experience in the community. “What it means is that you can go to your doctor with a broken arm and they will still try and suggest that it’s about your transition or hormones,” they say. “What that does is removes agency from care. But when I think about it from a cancer point of view, it adds an additional element of time to it. If something does turn out to be a cancer diagnosis, there is a risk of further proliferation of the disease.”

As a result, trans and non-binary patients often feel like they have to educate the clinicians on their needs rather than the clinicians educating themselves. “And when you’re going through a cancer diagnosis and treatment, the last thing you want to do is transgender 101,” says Rob. “All you want is your treatment.”

This burden for patients could be eased, Dr Berner says, with better communication between services and GICs, although there is still a lot of red tape that slows this process down. The urgent nature of oncology means that things happen quickly, often within a few weeks. “The GIC is a very different model: it’s non-urgent care but the volume is very big,” she adds. “So there’s something there about speed and ease of communication, because the GIC is not based within an acute hospital trust. That causes a delay in letters going back and forward.”

This is actually a wider issue in the NHS about communication between primary and secondary care, or secondary and tertiary care in specialist situations, although Dr Berner says things are moving towards emails rather than letters being dictated and sent back and forth.

“I think a big thing is relying on the patient to be the go between in services,” she says. “Don’t get me wrong, the patient needs to take ownership of their care, but it’s not their job to liaise back and forth between different clinics and services. It would be much better if someone just picked up the phone and spoke to someone in person or got everyone together in a room.”

Rob

Without better communication, knowledge and understanding in place, though, trans and non-binary people can still fall through the cracks, especially within an institution like the NHS, which O’Callaghan says is still very black and white. For example, “how you’re registered will determine and affect how you’re invited to screening,” they say. “So if you’re registered as female, you’ll be invited for your cervical and breast screening. But if you’re registered as male you won’t be, even if you have that tissue. You have to set up safety netting procedures to get around that. I think a lot of that is still a grey area for trans people.”

This once again causes extra work for the patient. “If you’re trans, the NHS doesn’t quite know what to do with you,” says Rob. “The onus goes back on the patient and you have to arrange your own screenings. That’s more work on top of your transition already.”

Ultimately, there needs to not only be equal care for trans and non-binary people but equitable care, too. Intersectionality in healthcare is key, O’Callaghan says, especially for LGBTQ+ and trans health. “And in the cancer world, they’re also moving more towards social prescribing,” they add. “What that means is that in primary care practice there will be someone that will help you make links with outside or third-sector organisations to help support your care. When I speak to these people in this field, I always remind them to take on board LGBTQ+ organisations, make their own connections with them and get to know that community, because the burden can’t be on the patient the whole time.”

Things like the chest-checking posters created by CoppaFeel! and Live Through This help ease this weight by providing accessible and inclusive resources. “The main point of this project was to fill a gap in the resources, give trans people information to promote their own positive health, answer questions and raise trans voices in the knowledge that it was built with trans people,” O’Callaghan says. “Given how things are at the moment, it’s important to me that there are positive examples of what we can do as a community to support each other and promote trans joy.”

For Rob, this involves sharing his own experiences so that it may help others. “I wish I had known that there would be difficulties with my hormones. I had no knowledge of that at all,” he says. “I would not want any other trans person to go through what I did and not come out at the end of it. I’m just so glad that I can give back something to my community. I think it’s brilliant, actually.”