The story behind THE FACE’s Ukraine cover

As the work prepares to be shown at Photo London, writer Serhiy Morgunov, photographer Jesse Glazzard, and creative producer Eugenia Skvarska reflect on what it was like to document the lives of queer soldiers during Ukraine's fight against Russia.

Society

Words: Serhiy Morgunov

Photography: Jesse Glazzard

Creative producer: Eugenia Skvarska

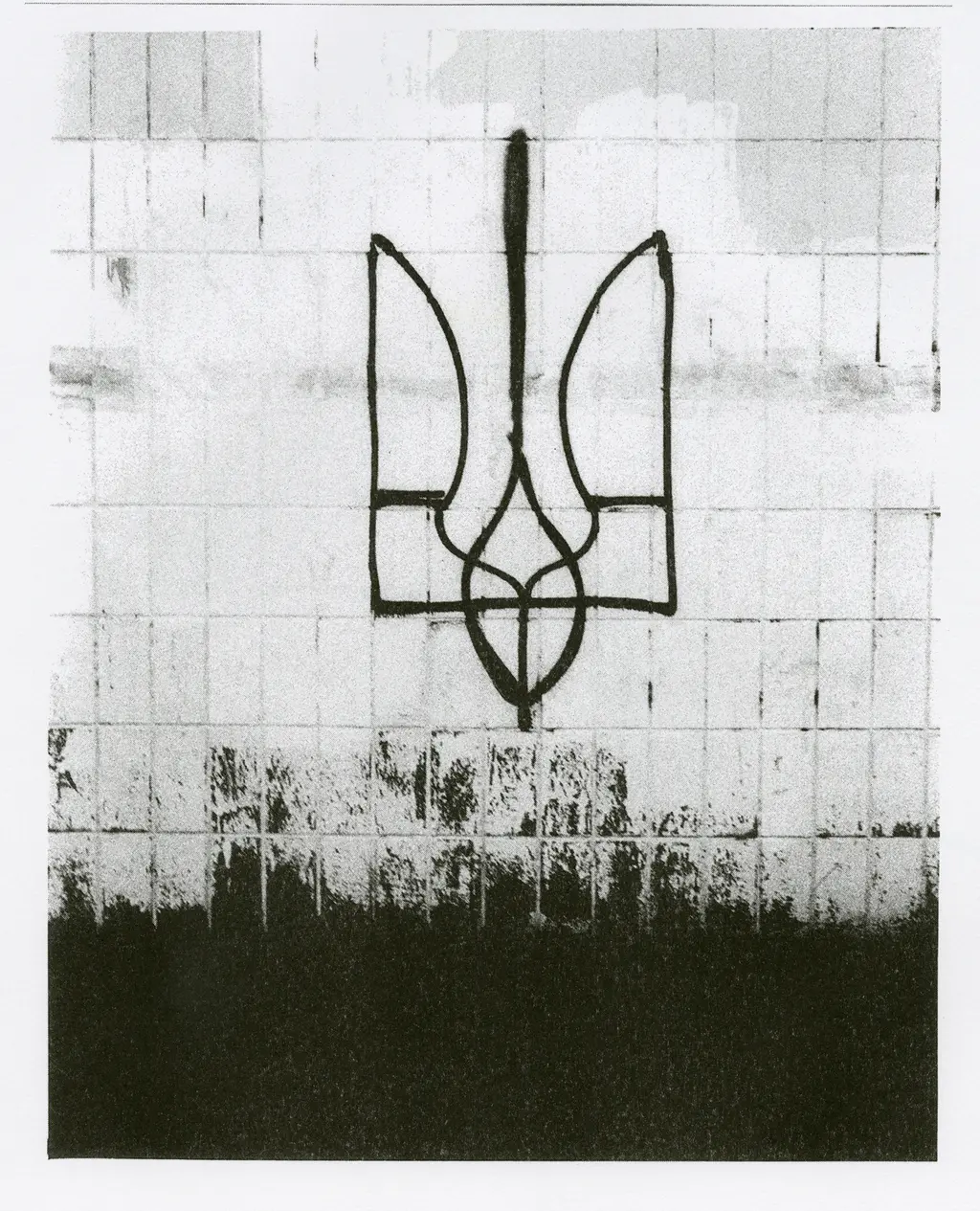

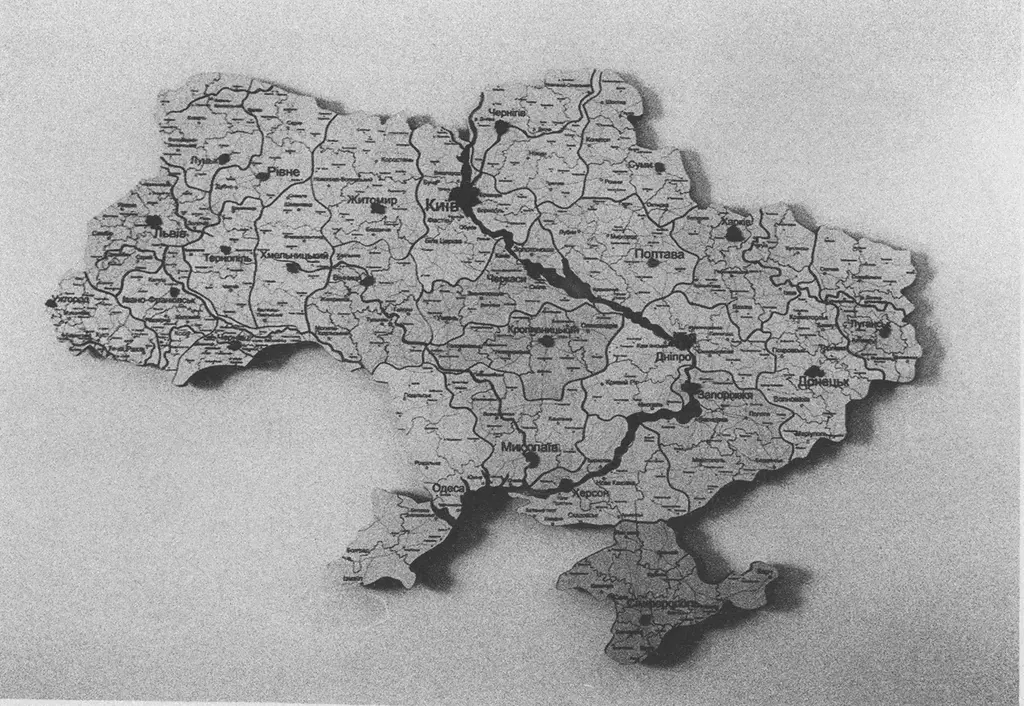

In November 2024, THE FACE published a cover story about a struggle that has, until recently, remained largely invisible: what it’s like to be a queer soldier fighting in Ukraine, a country fully mobilised against an existential threat to its existence.

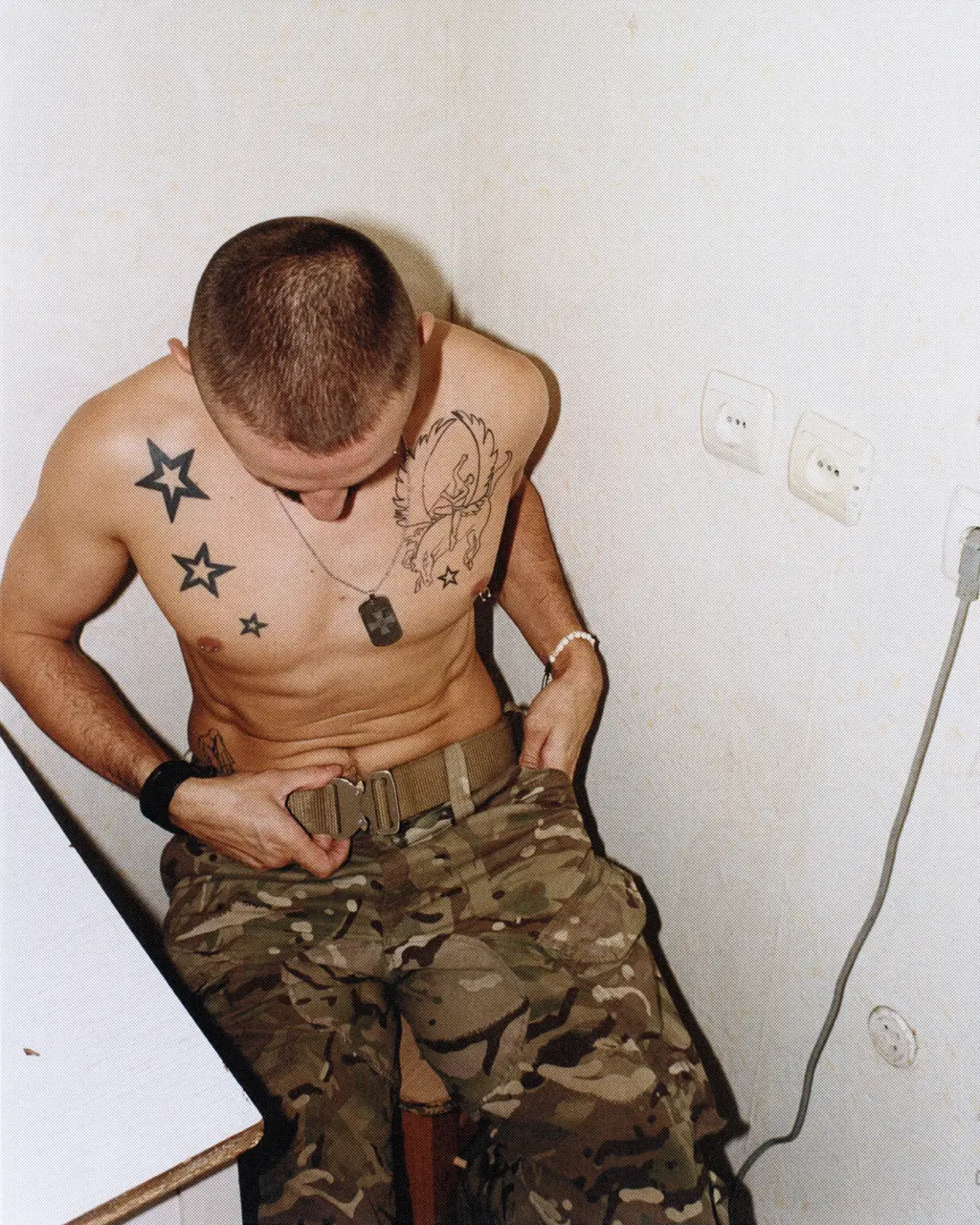

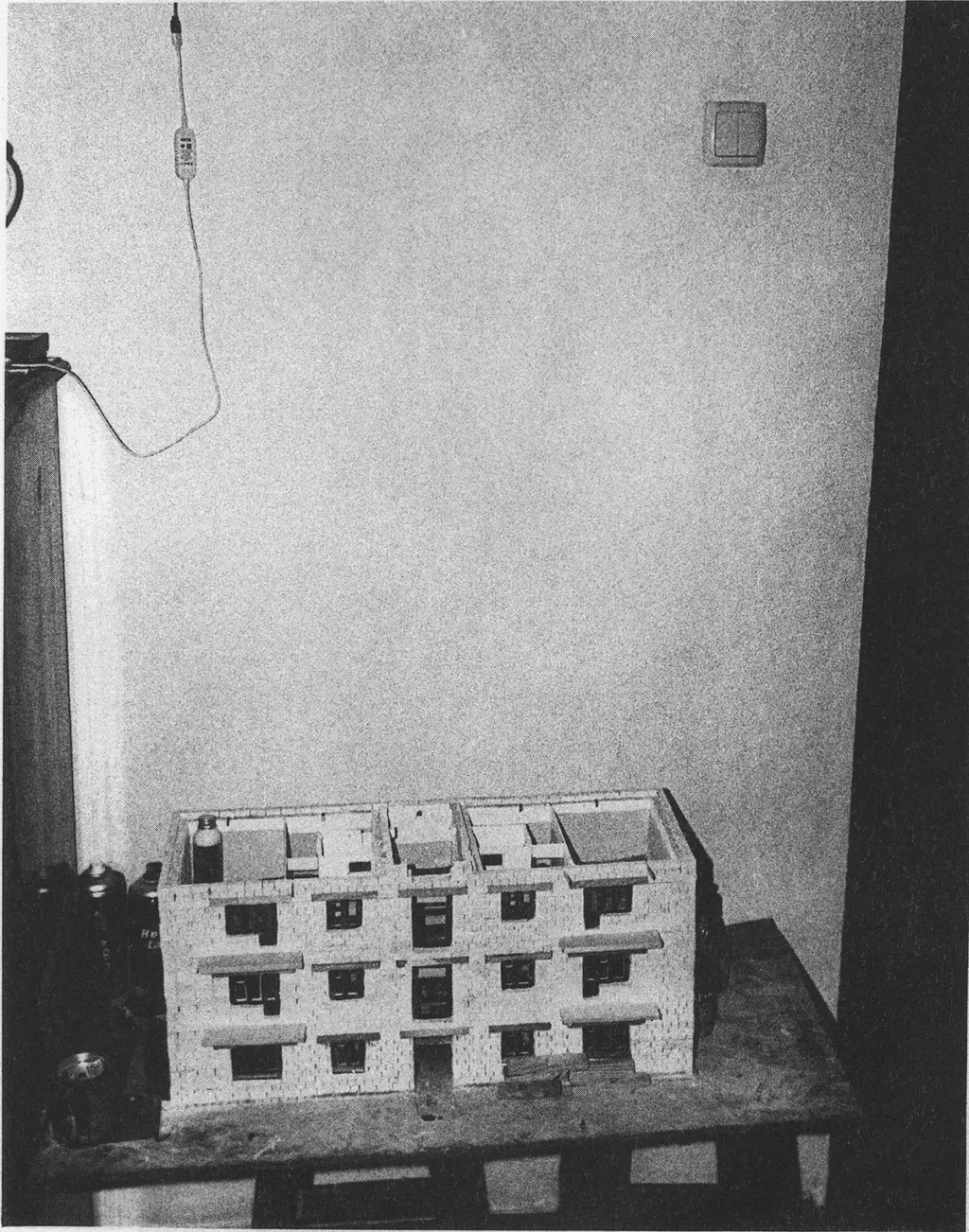

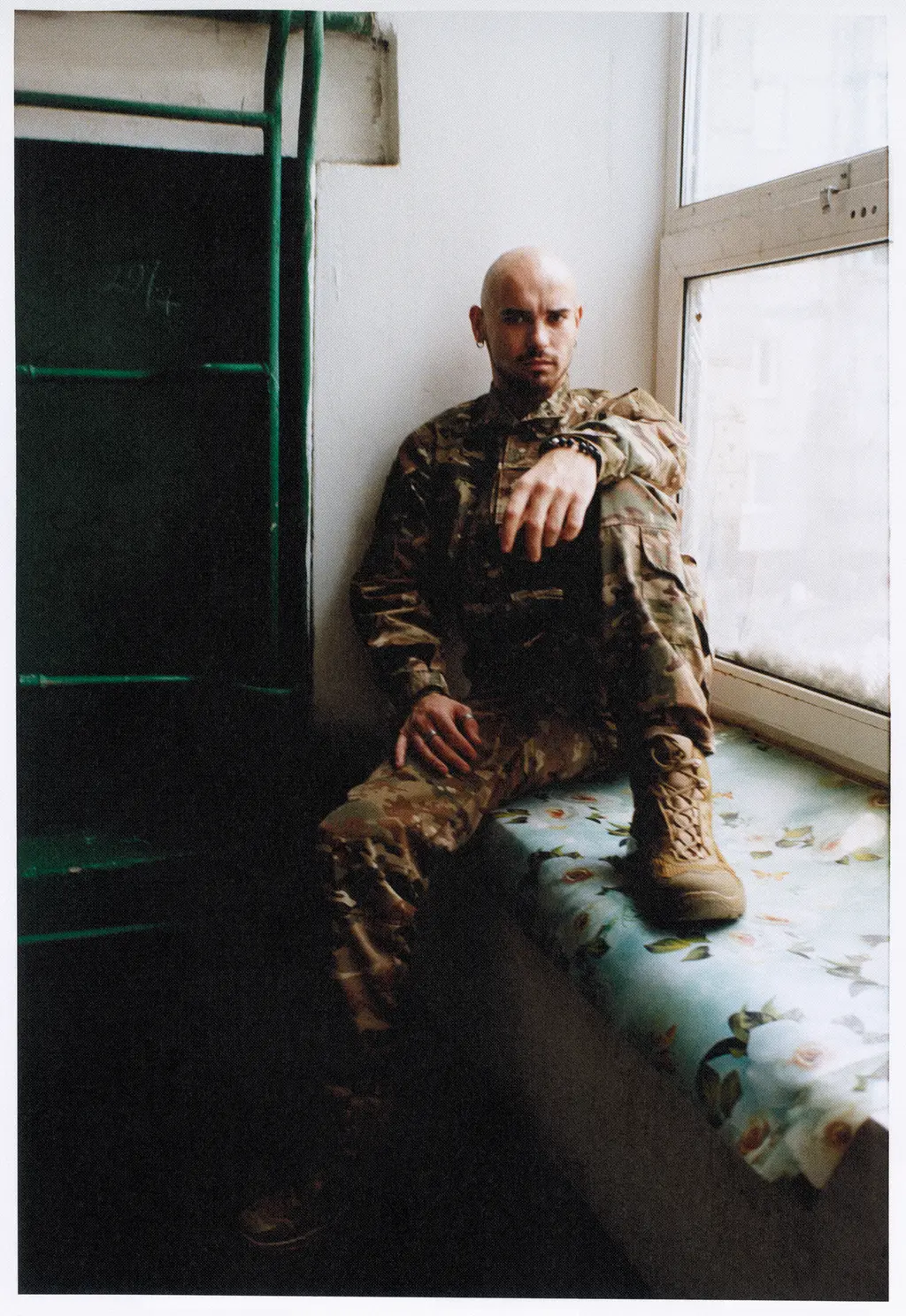

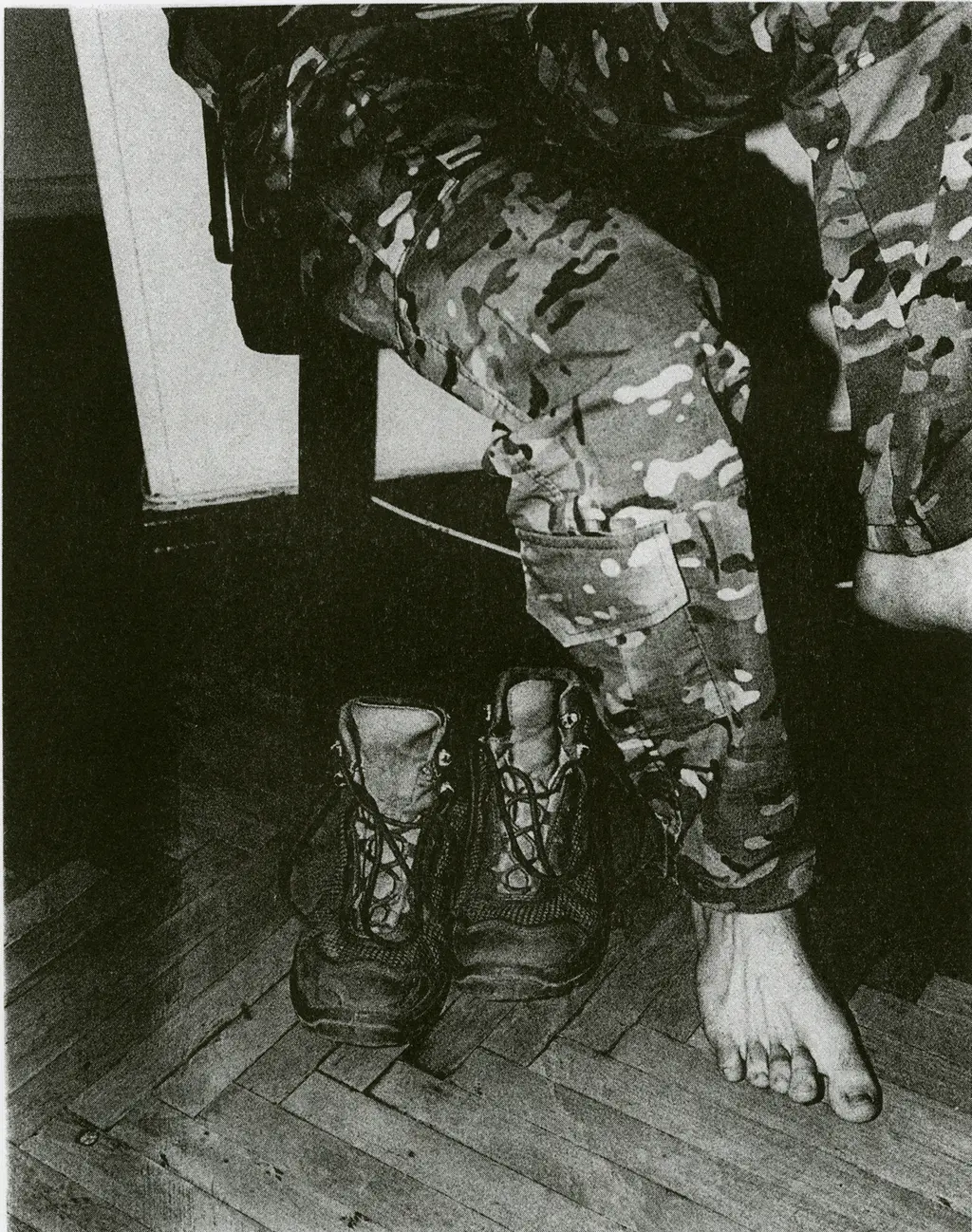

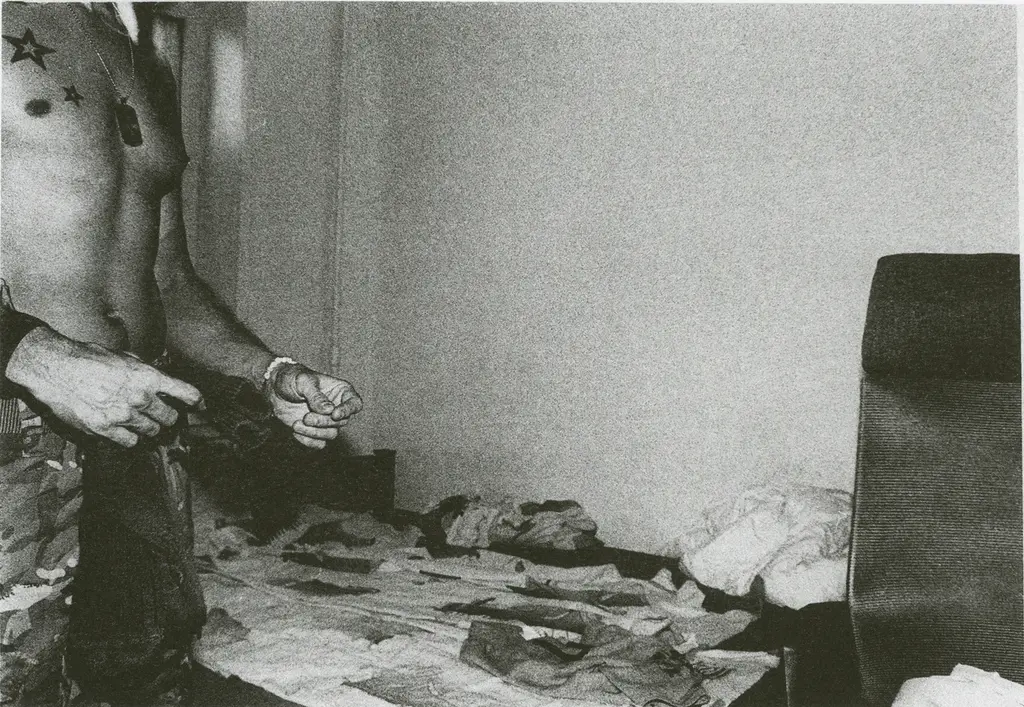

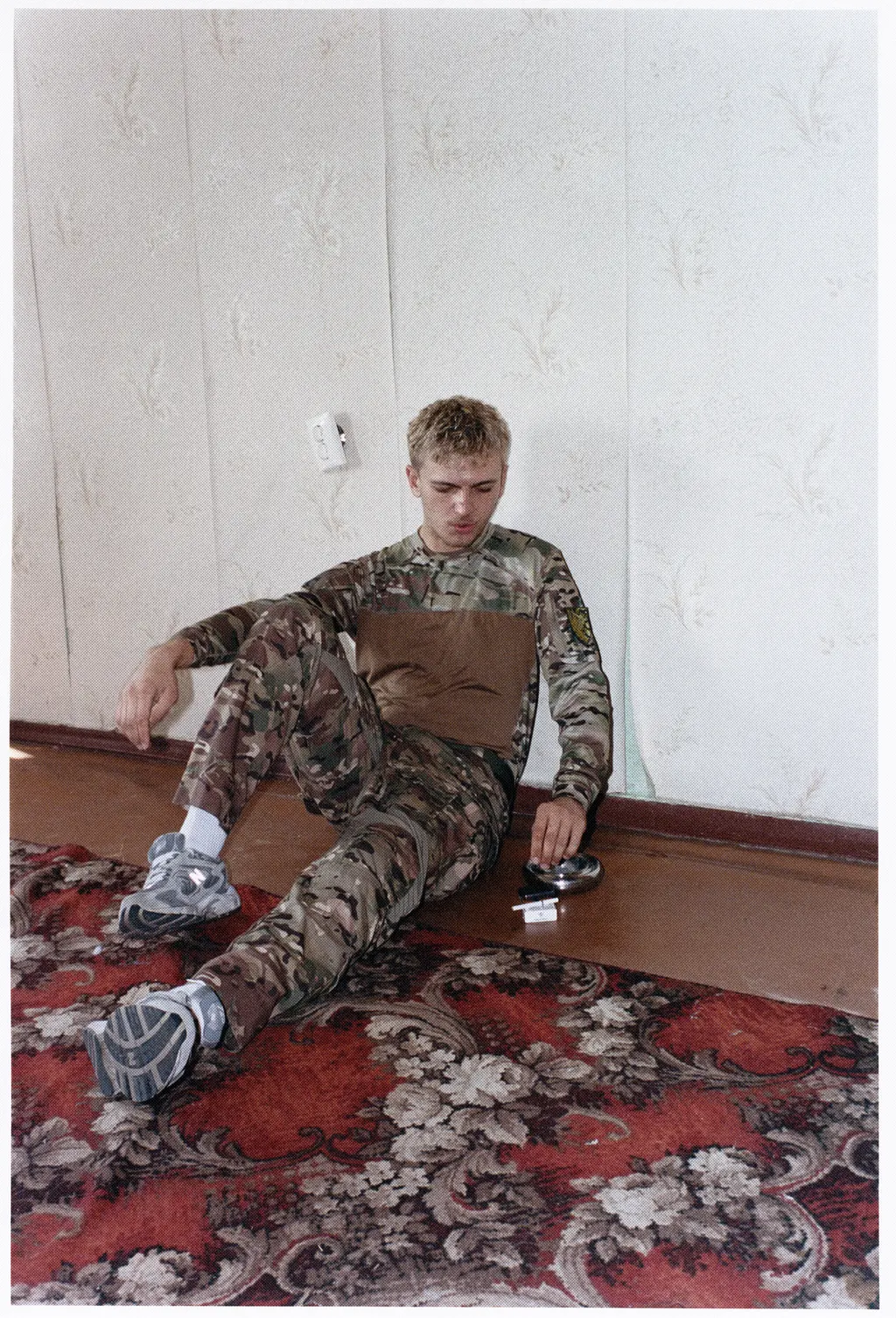

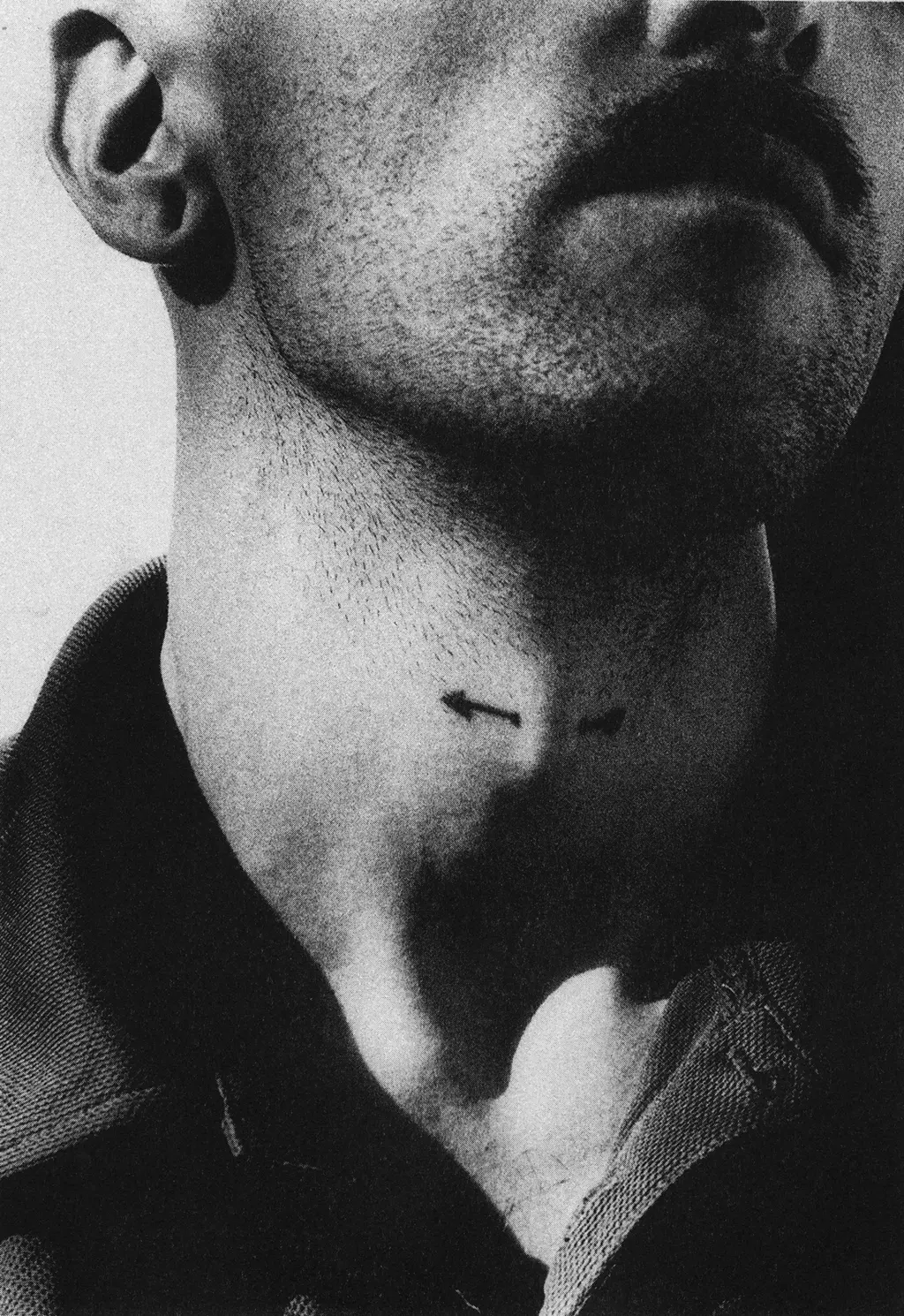

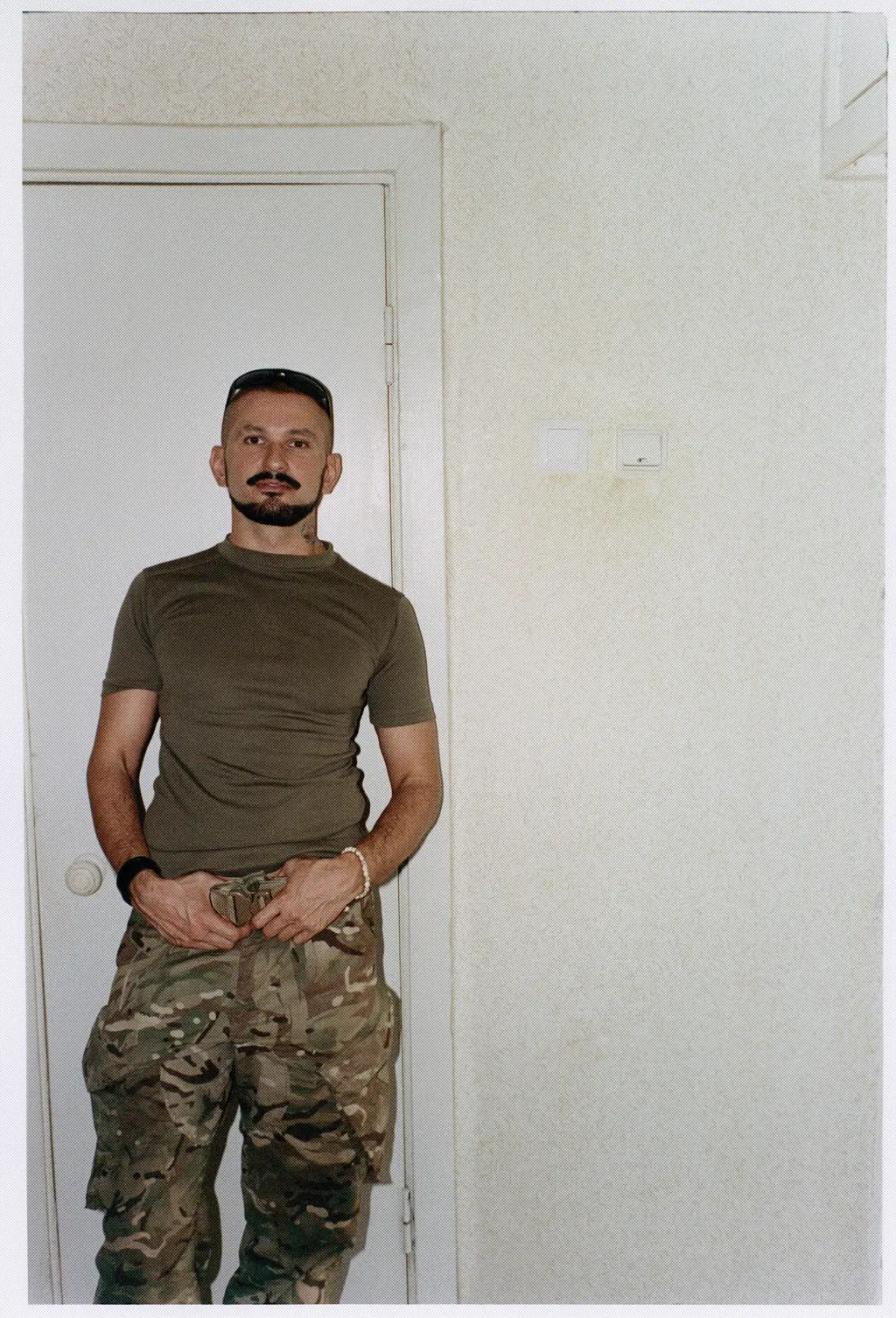

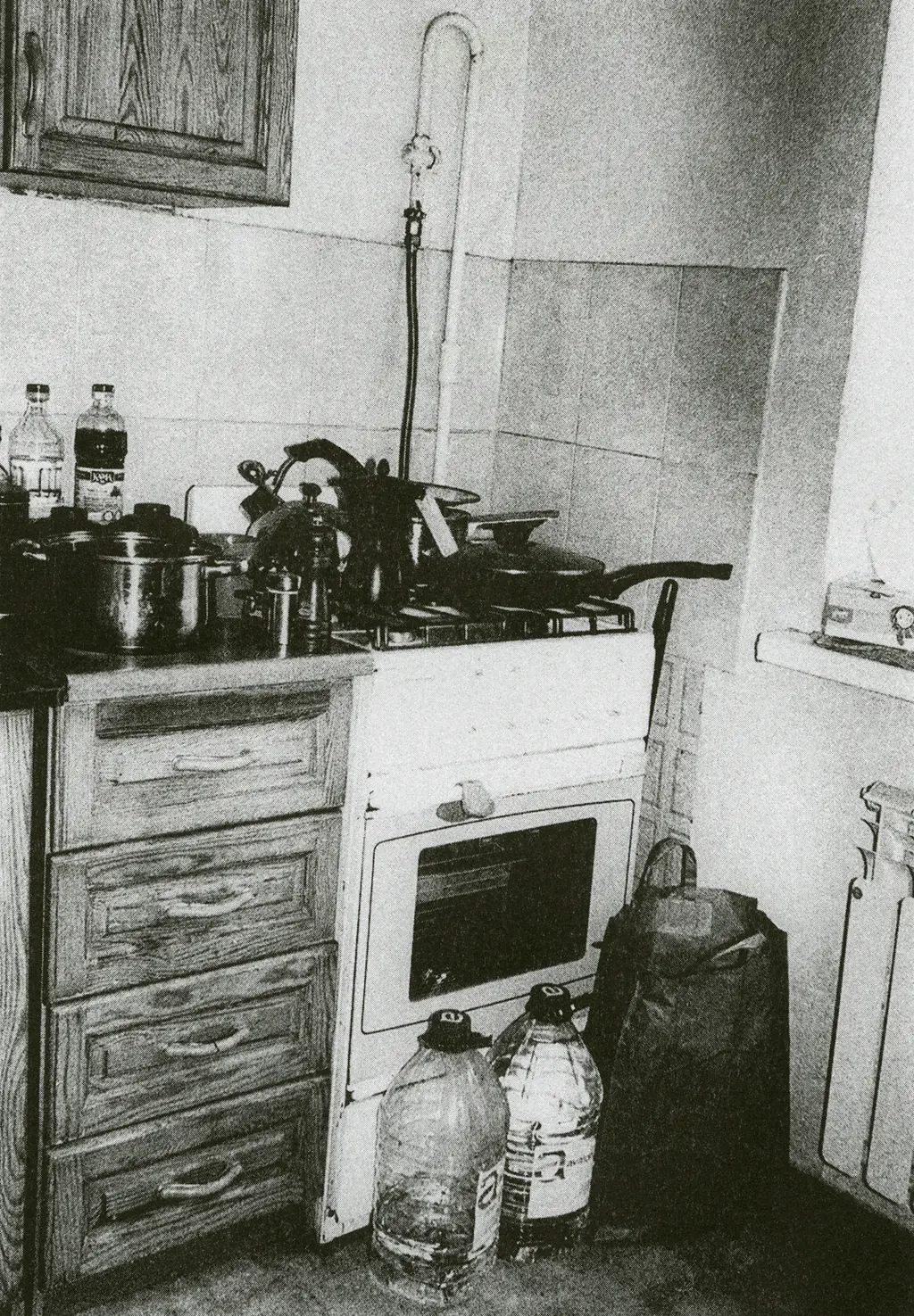

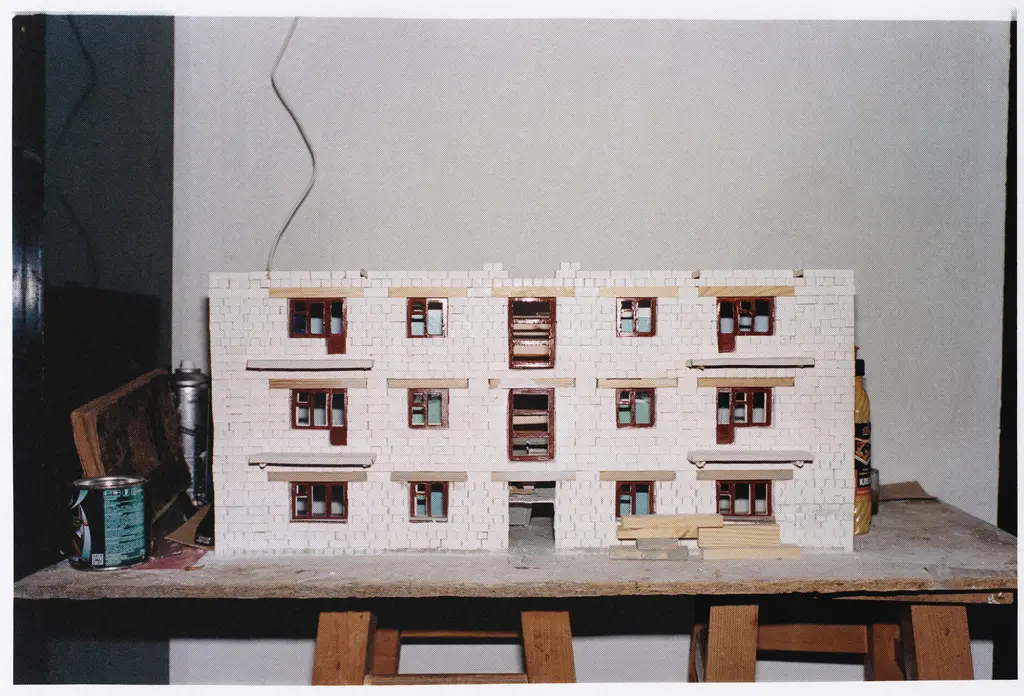

In Serhiy Morgunov’s extraordinary report, which was photographed by Jesse Glazzard and creatively produced by Eugenia Skvarska, the trio worked with the Ukrainian LGBT+ Military and Veterans for Equal Rights to speak to soldiers about their experiences. They focused on three men, Oleh, Oleksandr and Vlad, documenting what it’s like to be on the front line of two fights: one for country, and one, as Serhiy put it, for “civil rights, tolerance and acceptance.”

Below, read a conversation between Serhiy, Jesse and Eugenia about what it took – both physically and emotionally – to put their story together.

Serhiy: Whose idea was it to go to Ukraine?

Eugenia: Jesse texted me [saying], “Let’s catch up.” We talked about fashion editorials without any concrete ideas. I can’t even recall where this idea came from.

Jesse: Had you thought about it before we met?

E: Not really. But talking to you made me realise how naturally our work connected. Your focus on queer and transgender experiences linked perfectly with the Ukrainian reality, where queer people not only share common struggles but also face the added trauma of war.

J: That makes sense. Though I was a little worried – you’re straight. But people creating queer-focused work don’t necessarily have to be queer themselves.

E: I often have ideas just from talking to people. With Ukraine always on my mind, I naturally think about how projects can tie back to it. I even told Jesse, “Do you want to do this?” and offered to step aside, feeling it wasn’t my place to lead a queer-focused project. But then I realised this wasn’t just about queer identity. It was about my country.

It also challenges stereotypes about war. People in the West often imagine soldiers as hyper-masculine men who live for violence. But Ukraine’s war isn’t like that – it’s often called the war of civilians. Most of the people we photographed weren’t soldiers before the war. And focusing on queer people makes it even clearer that this isn’t about toxic masculinity.

Jesse, you mentioned feeling distant from Ukraine at first. I’m curious how that changed for you.

J: When the war started, one of my old tutors took in someone from Ukraine. I also donated clothes to a drive some friends were organising. But honestly, I didn’t read much about it. It just felt like another distant war.

And from your perspective, Eugenia?

E: On the evening of 23rd February, I was busy with work, late Zoom calls. Afterward, I stood on my balcony, looking at the city lights, the traffic in the centre. Everything seemed so peaceful. Then I went to sleep.

At 5 or 6am, my best friend called. He just said, “It started.” He didn’t even say the word “war” as if saying it would make it real.

I packed a small backpack with just my documents. I taped a cross on my windows, like I’d seen in movies. When I stepped onto the balcony again, the streets were empty. But the highways were jammed with cars. The silence was unbearable.

I saw neighbours running with suitcases and pets, some crying. I went to a store, bought a Swiss Army knife and dry food, trying to create a survival kit. That first night, I stayed in a bomb shelter near my house. No internet. No way of knowing what was happening. It was terrifying.

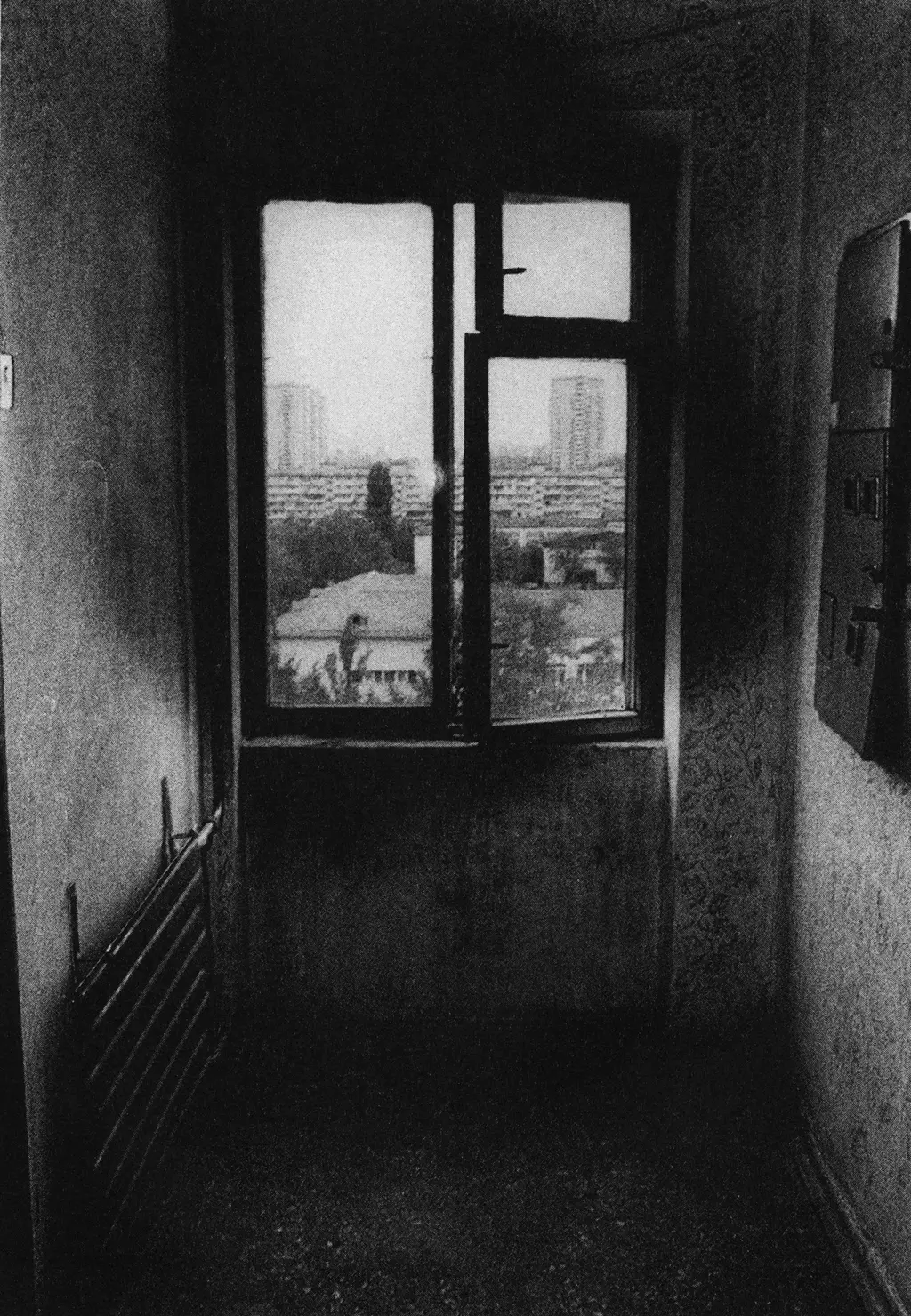

Without the internet, your mind fills the silence with the worst possibilities: maybe Kyiv doesn’t exist anymore, maybe we’re surrounded, maybe there are planes overhead dropping bombs. The thought that scared me most was Russians entering the city, raping and kidnapping people.

Tell me about your experience as a refugee.

E: My experience as a Ukrainian abroad exists on two levels. First, how others perceive Ukraine. When I arrived in England in 2022, I constantly heard, “Before February 24, I knew nothing about Ukraine.” Meanwhile, Russian culture was widely admired, with no awareness of Ukraine’s contributions to it, or how Russia used Ukrainian resources while erasing its identity.

What frustrates me most is that the West grew tired of Ukraine before it even truly learned about it. I don’t blame people – Ukraine is still far enough that they can afford to look away. But that’s the problem. Russian culture has had centuries to build a foundation, while Ukraine remains a footnote. And despite being part of Europe, sharing its values, we still struggle to be seen as equals.

Since the war began, I’ve lived in Warsaw, Berlin, Paris and London. Everywhere, I’ve seen Russian inaction. Meanwhile, we believe every story, every repost. At best, Russians pity us, but how do we explain that we don’t need their pity? We need them to take action. To openly challenge Russian imperialism. But so far, only Ukraine and the former USSR countries are doing that.

As a Ukrainian, it’s painful to witness history repeating itself. This has all happened before.

Viktor

Hryts

Jesse, how was your journey to Ukraine? What was going through your mind?

J: I flew to Lublin [in Poland], then took multiple trains. I was more worried about getting through border control than anything else, wondering if they’d question why a British person was coming to Ukraine.

I didn’t have any expectations. Eugenia had warned me we might only find two or three soldiers for the project. But I thought, it’s worth the risk.

When I arrived in Kyiv, I saw people crying at the train station. I felt weirdly calm, maybe because of my difficult upbringing. But then there was this massive explosion. That’s when I realized: oh fuck. I actually came to a war zone.

E: That morning was awful. From the moment Jesse arrived, I felt responsible for his life. But during a ballistic missile attack, there’s no way to move around Kyiv safely. I was on the phone with him the whole time, trying to keep him calm.

I told him to go underground: Kyiv’s metro stations are used as bomb shelters, just like in London during the second world war. But the apartment I found for him was too close to a children’s hospital that had been hit before, and he didn’t want to stay there. So I moved him to my apartment.

I thought he’d need a day or two to settle in before starting the project, so I scheduled my own work meetings. But that free time only gave him space to overthink. Jesse texted me, “I’m going back. I found a train ticket back to Poland.” I told him, no way. You’ve already faced the worst. It will be fine.

I rushed to him, told him we’d go for a walk. Then I took him to a meeting with a fashion client because, yes – Ukrainian fashion is still working. It was the first Ukrainian fashion week since the full-scale invasion.

J: I had just survived a missile attack, and a few hours later, I was in an office, watching people work like nothing had happened.

E: The client told him, “Don’t worry. This office is a bomb shelter.” I told Jesse, “Look at these people, they too just survived a ballistic attack, like they’ve survived so many before. And they’re still here, still working, still creating a new fashion collection.”

I said, “Jesse, you just came from Paris with your incredible transgender project. Now, this is another perspective on queer identity – one the world hasn’t seen before. This is the first project where queer Ukrainian soldiers are openly sharing their stories. It’s important not just for Ukraine but for the global queer community. Historically significant things are never created from a place of comfort. You’re already here. Let’s try.”

J: It snapped me back. I realised I had to stay.

Where were you in Kyiv during this period? How did you take in the environment, the atmosphere? You also saw a different side of the fashion world during the war. How did you process everything?

J: The moment I arrived, I started educating myself, watching [Evgeny Afineevsky’s 2015 documentary] Winter on Fire and reading about Ukraine. The energy felt revolutionary. I realised, these people fight.

As soon as we met the first soldier, I saw a familiar pattern. I don’t know if you’d call it an industry, but in a way, the army – whether in Ukraine or the UK – is often made up of working class people. They’re the ones who end up fighting wars. But I knew my role wasn’t to come with an opinion but to listen.

I kept thinking, How do people go about their lives like this? How do they not think about the war 24/7? I also felt sad, especially for the kids. How does war become such a permanent part of childhood?

What were your thoughts on meeting all the soldiers you worked with on this project?

They kept shifting. Their stories were intense: fighting on the front line, Russians shooting at them. It was all so immediate, but at the same time, my brain couldn’t fully process it.

What stuck with me most was how suffering creates incredible kindness. No matter what they had endured, there was this quiet resilience. Beyond the war, they made small gestures: offering us coffee, carrying themselves with dignity. It wasn’t just about survival, it was about holding onto something deeply human.

Are there any particular encounters that stood out?

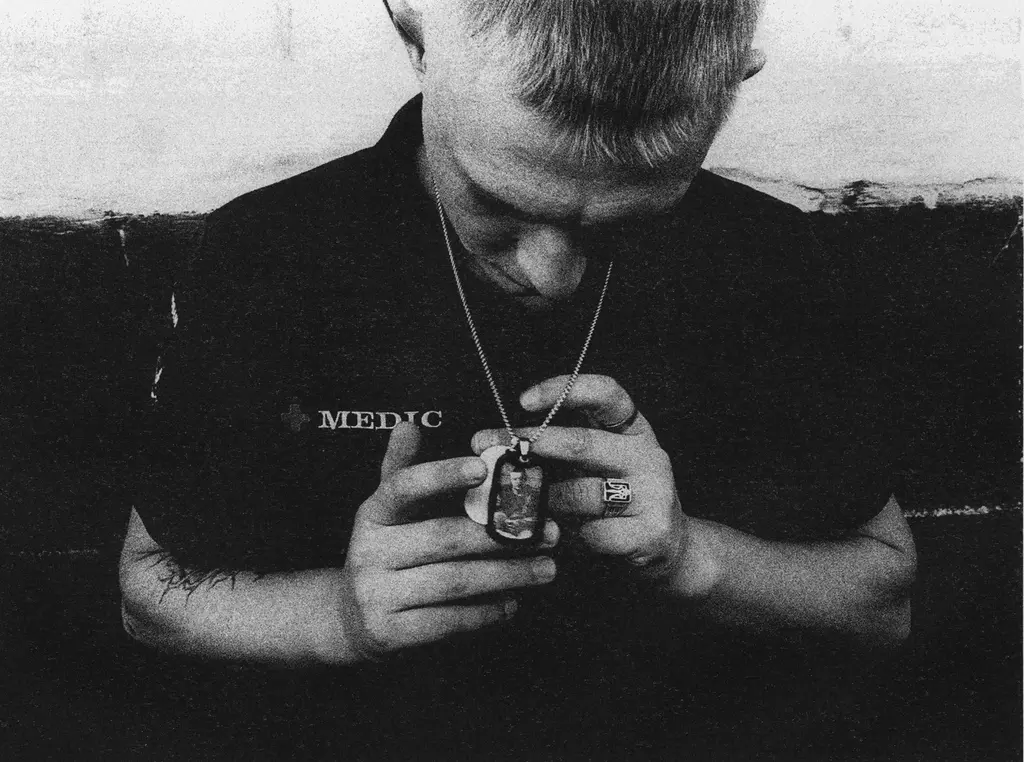

J: Vlad, [the 25-year-old coffee shop owner who lost his boyfriend, Ruslan, during the war] – his story stayed with me. Maybe because we all long to meet someone we love, and losing them is unbearable. I’ve lost both my parents, so I felt his pain deeply. But what struck me was how he could be laughing the next moment.

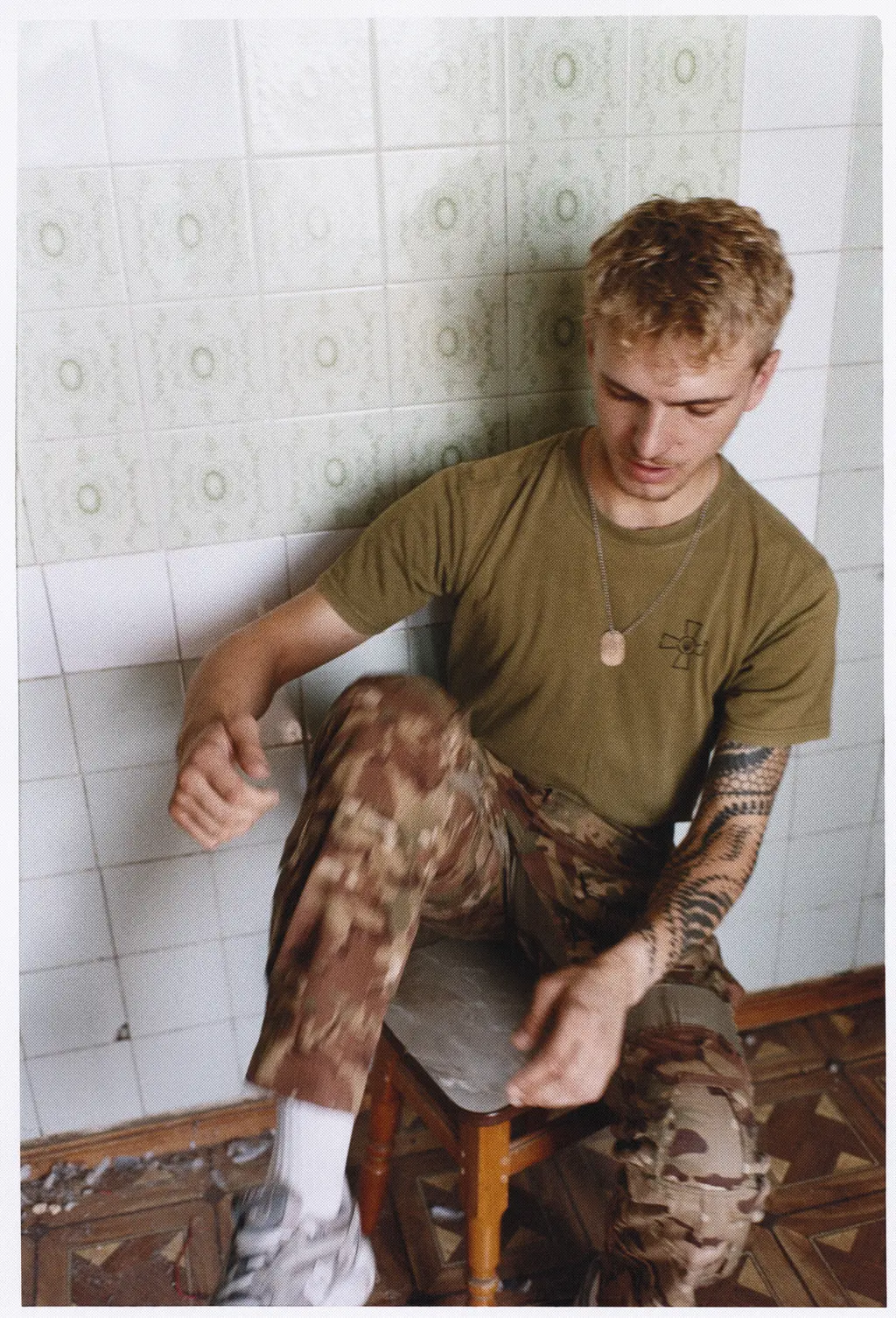

Then there was another soldier, Dmytro, who showed me his leg wound. When he pulled down his trousers to reveal the scar, I felt an immediate rush of emotion. As I raised my camera, I thought, should I even take this picture? It suddenly made everything feel brutally real.

E: Even as a Ukrainian, I’m still learning how to talk to soldiers. Every interview brings back painful memories. That’s why, when photographing them, I tried to focus on just being together: laughing, sharing moments. But even so, their stories broke my heart.

We met two or three soldiers every day, each with completely different lives and experiences. And I could see how it was changing Jesse – his eyes, his expressions. There were moments of shock and deep listening.

I’m grateful for Victor, the founder of the Ukrainian LGBT+ Military and Veterans for Equal Rights organisation. He’s kind and calm, and his knowledge of Ukrainian history helped us see these stories as part of a much bigger fight. He’s been involved in this war for years, even before the full-scale invasion.

J: Victor was incredibly generous in sharing his perspectives. I wasn’t really educated on Ukrainian history, and at times, I felt like I should have known more. But he never made me feel bad about it. He just shared what he knew.

Roman, 27

Roman

Vlad

Jesse, Eugenia mentioned how interesting it was to watch your transformation throughout this project. Did you notice that change in yourself?

J: I think it started with stress and ended with falling in love with the country and the kindness of people.

They welcomed me, a transgender man from the UK, into their homes, into their lives, sharing their stories without hesitation. If they weren’t kind, they would have been suspicious. But they weren’t. They just accepted me.

I don’t recall every conversation, but I remember the feeling of being overwhelmingly welcomed. People appreciated that we were there, doing this work. Even though we were strangers, they were open, warm in a way I wasn’t used to.

How did you feel as a trans person in Ukraine? Did your experience challenge or reinforce any stereotypes about Eastern Europe?

J: No one really knew or cared. One person asked, “You’re trans? What’s up?” I just said, “Thank you,” and moved on. That was it.

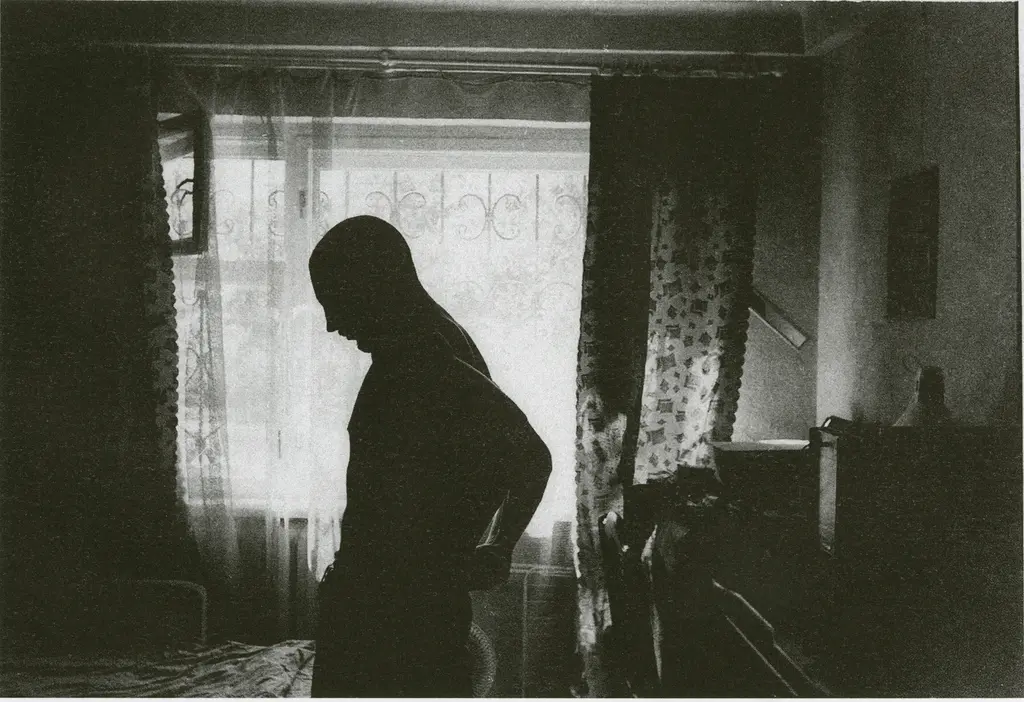

You mentioned the way Ukrainians fight. Did you feel that same spirit in the people you met, not just in their stories but in the way they carried themselves?

J: I felt it at the nightclub K41. I actually recorded the sound because you can’t take photos there, and it felt almost spiritual. The energy, the voices, the way people screamed – not in fear, but in a raw, powerful way. It was like pure freedom.

E: I wanted Jesse to experience K41 because one of the strongest forms of resistance is simply having a good time. It feels like stepping into a portal, leaving behind the war, the stress, the fear, even just for a moment. It’s a space where soldiers returning from the front lines can dance, relax, and feel free.

E: Jesse, I remember how exhausted we all were. At some point, you decided to leave a couple of days early. You messaged me, saying, “Eugenia, I feel like we have enough, we’ve photographed seven people.” And I remember you feeling really sorry about that decision. Do you think this trip changed you?

J: The reason I left early was because a drone flew really close to the apartment. I heard the sound, and it went through my entire body. I believe trauma is stored physically, and at that moment, I thought, If I go through this again, I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish the work. I wanted to give this project the attention it deserved. But if I stayed and experienced another shock like that, I was afraid I’d shut down completely.

Leaving made me understand things more deeply. It made me realise why this work mattered. And I felt privileged – privileged that I could just send a message and say, I’m leaving, and actually leave.

So many people don’t have that choice. That realisation changed me. I think I care less about trivial things now. My entire perspective has shifted.

E: How did it feel to return to London after everything you experienced?

J: I felt like people in the UK prioritise the wrong things. Coming back, I noticed it even more. We should care about human life, about the planet, but we don’t. Instead, we waste energy on meaningless problems.

When you face your own mortality, when you see what actually matters, it changes you. I remember coming back, hearing people complain about the most trivial things, and just thinking, shut the fuck up.

People here have everything, but they don’t even realise it. They don’t feel grateful for the access, the security, the ease of life they have. And that realisation hit me hard.

Viktor

Why do you think it’s important for artists and people in fashion to reflect on crises like war?

J: Artists have always reflected the world we live in. Fashion should do that too. Our generation wants to engage with what’s happening in the world. Fashion offers a space for a softer, more accessible discussion than mainstream media. We need to understand war and the world’s horrors not just through news outlets, but in all creative spaces.

How did this experience change your perspective as a photographer?

J: It made me realise I need to tell more stories from disadvantaged communities. I used to think that, as someone from the UK – with its colonial background – I couldn’t step into spaces I didn’t directly relate to. But Ukraine changed that. It showed me that sometimes, an outsider can bring a fresh perspective that might not have been considered otherwise.

As a straight person, working on this story was important to me, too, because it’s about freedom and equality. I hate when people separate into bubbles. It isolates us. Communication is key.

J: In the end, we’re all just people. Real change happens when we come together. In the end, what truly matters is keeping each other alive.

See the work as part of The Face presents Jesse Glazzard x Eugenia Skvarska at the discovery section of Photo London, 15 – 18th May at Somerset House.