The New Cross Fire: Steve McQueen and survivors on trauma, race and rage

Uprising, the director’s new BBC documentary, explores the events surrounding the deaths, 40 years ago, of 14 young Black people after a South London house party.

Society

Words: Craig McLean

CW: The following article contains graphic descriptions of the New Cross Fire

“This is all that remains of the three-storey house where nearly a hundred young West Indians were celebrating at an all-night birthday party for two young friends. Just before six o’clock this morning, the singing and dancing gave way to panic, as flames shot through the upper floors and screaming teenagers began to leap from the windows.”

So ran the voiceover on the outside-broadcast news bulletin on Sunday 18th January 1981, excavated from the archive and rebroadcast in Uprising, a new three-part BBC documentary from Turner Prize-winning artist and Oscar-winning filmmaker Steve McQueen.

In all its RP diction and language of the times, the TV report was revealing to the wider world the horror of what immediately became known as the New Cross Fire – or, in the words of the action committee formed in the South London neighbourhood, the New Cross Massacre.

Thirteen young Black people, aged between 14 and 22, died after a fire broke out at 439 New Cross Road, a three-storey Georgian terrace house with a basement. A fourteenth party-goer, 20-year-old Anthony Berbeck, died two years later on 9th July 1983. “That fire had a massive, massive impact on Tony,” says his friend Richard Gooding. “Tony was alright before.”

It had a massive impact on Richard, too, who was 18 at the time and had stopped off at the party earlier in the evening to collect his siblings (they turned him away because they were enjoying themselves too much). His younger brother David, 17, was badly burned. His little sister Denise, 11, survived too – just – after a still-unknown stranger carried her to safety halfway down an exterior drainpipe. But in the burnt-out shell of the building their brother Andrew, 14, was found on a bed with his coat on, the youngest victim of the New Cross Fire, identifiable only by a fragment of clothing.

“It just tore the whole family apart,” remembers Denise. Miraculously unscathed, she still spent five days in hospital. “You’ve got one son who died, another in hospital, then me – it was just tragic for the family and very hard to recover from.”

Wayne Haynes has also struggled. Now 58, he was playing the music that night, along with the friends with whom he ran the Gemini sound system. After the fire broke out at dawn, he ended up on a window ledge behind another partygoer. He also found a drainpipe, but as he was desperately descending it came away from the wall and he fell through the roof of an old outside toilet.

“I have landed on my right leg,” he recalls in Uprising. “And my right leg ended up in my chest. I’d smashed my hip into 100-odd pieces. Broke my right leg, broke my shin, smashed my foot up.”

In hospital, Wayne was told that doctors would have to amputate his leg at the hip. He also suffered appalling burns. As he puts it: “They had to get me a blind physio because nobody else would touch my arms. A third of my body got the worst burns.”

For a 17-year-old lad in excruciating pain, even if his leg wasn’t ultimately amputated, this was beyond comprehension – as was the loss of so many of his friends. Wayne’s girlfriend, Rosaline Henry, 16, died, as did his mates from the sound system: Gerry Francis, 17; Steve Collins, 17; Owen Thompson, 16; and Glenton Powell, 15.

Trapped in hospital in agony for weeks, months on end, Wayne remembers thinking: “You might as well have just killed me in that fire.”

Meanwhile, in the outside world, a different pain: the fight for justice for the dead, injured and traumatised. Who started the New Cross Fire and why?

Most in the local community believed it was a racist attack, the latest in a wave of assaults, instances of arson and everyday discrimination during an era and place where the far-right National Front were (literally) on the march and the Thatcher government was fanning the flames of discrimination. The police thought otherwise.

Forty years on, that fight for justice continues. No one was ever accused, far less convicted, of the New Cross Fire. Up until now, the most visible testimony to that loss of so many young lives was a row of 14 trees planted in their memory on Hackney Downs in northeast London.

It’s that trauma, that injustice, and that wider societal and political context, that McQueen trenchantly explores in Uprising. As Wayne states passionately to the filmmaking team: “Nothing in our case has gone right. And do you know what? It’s not fair. It’s not right.”

Uprising appears shortly after McQueen’s brilliant five-film Small Axe series. Ask him why he’s now turned his prodigious talents and energies to this story and the documentary’s executive producer/director’s reply is forthright: “These events were just pivotal moments. And they were pivotal moments that somehow got brushed underneath the carpet [for] the wider public. And they needed to come out into the light.

“These are historical moments, not just for Black British people, but for British people in general – because these events have reverberated throughout the nation, and through the bloodstream of the nation. One aspect informed all the others.”

That latter point speaks to the framing of Uprising. The first episode, titled Fire, paints a vivid picture of early ’80s London: National Front graffiti everywhere, Margaret Thatcher proclaiming white Britons’ fear of their culture being “swamped” by immigrants. Wayne talks of the readiness of the police to “kick hell out of you” in the back of the van – if, of course, you were Black.

It’s an account corroborated by another interviewee, Peter Bleksley. He was a newly qualified teenage copper in Peckham and recalls the propensity of his colleagues to ensure youth were “fitted up with bags of drugs [or] offensive weapons”.

That endemic racism frames episode two, Blame. In the aftermath of the fire, witnesses claimed to have seen someone launch a petrol bomb into the house; the police and media seemed to want to find any other cause possible.

That, in turn, tees up episode three, The Front Line. It’s titled after the local name for Railton Road in Brixton, “a place of resistance… a Black stronghold” in the words of activist Leila Hassan Howe. The third film is blessed with fantastic footage from the personal archive of DJ Don Letts. “What’s special about it is that it’s a young man filming a world he’s in, rather than some of that almost anthropological, BBC traditional archive,” says executive producer Nancy Bornat. “Don Letts just gives you Brixton as he was experiencing it as a young man.”

WAYNE HAYNES

That summer, the Brixton riots broke out, a direct consequence of the simmering rage felt in the wake of the New Cross Fire and general police persecution of the Black community.

Reflecting on the aftermath, novelist Alex Wheatle – imprisoned for his part in the riot and himself the subject of the fourth Small Axe film – says in Uprising: “The level of damage was unbelievable… and this was just before Prince Charles’ and Diana’s wedding. So you had this weird juxtaposition – the Establishment was gearing up for this royal wedding and yet the country was going up in flames. It was quite something.”

British society was split, people were divided, race relations were abysmal. In the words of Lord Scarman, commissioned by the Government to report on the worst riots Britain had seen in decades: “We all carry the blame.”

As McQueen said, one aspect informed the other.

The party at 439 New Cross Road was a joint celebration for Yvonne Ruddock, who was turning 16, and her friend Angela Jackson, 18 on the same day. As rice and peas, curry goat and chicken were cooked in the ground-floor kitchen, people began arriving from 8.30pm onwards – friends, family, “generations” of people, with Denise Gooding, at 11, the youngest.

The party was held on the first floor, which is where Wayne and his friends played their records – big tunes of the day like At the Club by Victor Romero Evans and Paradise by Jean Adebambo. At 5.30am, Wayne could still see a lot of people dancing. Kingdom Rise Kingdom Fall by Wailing Souls is the last tune he remembers hearing.

At around 5.42am, partygoer Leslie Morris discovered that the ground-floor front room was totally ablaze. A window exploded, “glass flying everywhere”. Upstairs, Wayne could smell burning, but he wasn’t alarmed – his amps often smelled like that. But heading out to the stairs to check he saw smoke.

“Fire!”

The electricity went out. In the dark, panic.

“The whole place just went mad,” says Wayne in Uprising. “And I remember it getting really hot. Heat was coming up from underneath.” He thought he was sweating, but it was his skin peeling off. “It felt like I’d got sand all over my face. And the more I wiped it, the more the skin kept coming off my face.”

Denise, meanwhile, was on the top floor, enveloped in “thick black smoke… The heat from the smoke is so intense, I can remember feeling like I’m being pushed. We’re all trying to fight to get to this window… I’m only 11 and I remember thinking that I haven’t even lived my life and this is it.”

Then she felt herself being lifted by a mystery person. Having carried her halfway down a drain pipe, they left her with the words, “you’re on your own now”. As Denise says to me now, without that hero or heroine – who it seems likely died in the fire – “I definitely would not be here”.

Another attendee, Andy Hastings, also interviewed in Uprising, remembers boys trapped up at the top of the house, taking running jumps, “coming flying out of the windows. And they had to jump because there were railings [on the ground] and they obviously realised they had to pheooow,” he says, making a diving motion with his hands to demonstrate from how far up and how far out they had to jump.

Outside, survivor Sandra Ruddock saw “kids lying on stretchers, burnt till they were pink, and the smell of burning flesh, that’ll go to my grave”. Her husband Paul Ruddock, 22, who she’d married the previous July, died three weeks later. The nurses got him to “semi come round” to put her name and kisses on a birthday card. Sandra turned 22 that day and was five months pregnant with their child.

Paul’s sister Yvonne, whose party it was, also died in hospital. She had been recovering, but seemingly got out of bed one night, fell, banged her head and re-haemorrhaged.

Hastings tells how his dad phoned the police to try to locate his son. “Police said: ‘What’s your son look like?’ ‘Well, he’s white.’ He said: ‘Doesn’t matter, they’re all black now.’ Charming.”

Peter Bleksley, the retired copper, recalls a similar unfathomable callousness. The joke going around amongst his colleagues was that New Cross should be renamed after another corner of London, Blackfriars. That is, Black-fryers.

By the Sunday evening immediately after the fire, the New Cross Massacre Action Committee (NCMAC) had been formed and was determined to push the authorities to find the perpetrators. Many were convinced a petrol bomb thrown into the property was to blame. Fire forensics found no evidence of that inside the house, although a mysterious object, possibly an incendiary device, was found in the front garden.

By Tuesday, victims’ families were receiving anonymous letters, celebrating the deaths. Wayne’s mum received two death threats. There were messages warning of racist attacks on victims’ funerals.

Meanwhile the police were more focused on a non-existent fight amongst partygoers as being the cause of the fire. They brought Denise in for questioning, a child not long out of hospital who’d lost her brother.

“That was horrible,” she tells me now. “They were trying to put words into my mouth – that I saw a fight, that people saw me, so they knew I saw this fight… It was just relentless – this went on till about 1am. And these people who they were trying to implicate were my friends, who I knew from the family [who lived] downstairs. It was very harsh. Even though my dad was there, he didn’t know how to react, because these were the authorities. It was a very scary situation.”

This bullying and manipulation continued until “they wore me down and got me to say what they wanted [about] all these things I didn’t see”.

Wayne, though, is adamant. “The problem is the police manufactured this thing about a fight at the party,” he says over the phone from his home in Lewisham, not far from New Cross, “but there was never a fight at the party. I know this for sure, because I’ve spoken to nearly everybody who was there at some point or another. There was no fight at the party,” he states intently.

“Why did they manufacture that? Because now instead of really investigating what happened, that’s giving time for that trail to get cold.”

Four weeks later, on the 14th of February, 49 people died in a nightclub fire in Dublin. “Disco of Death” ran the headline in the Sunday Mirror. The Queen and Prime Minister Thatcher sent messages of condolences. They’d sent nothing to the victims of New Cross, young people who’d died in their city, in their country.

As activist, poet, publisher and chair of the NCMAC John La Rose said at the time: “That’s a state of barbarism.”

Or, as Grenadian writer Gus John tells McQueen’s team: “We didn’t feel that Britain owned that tragedy as something that had happened to a section of itself. The state saw us as a race apart, a people apart. We did not matter.”

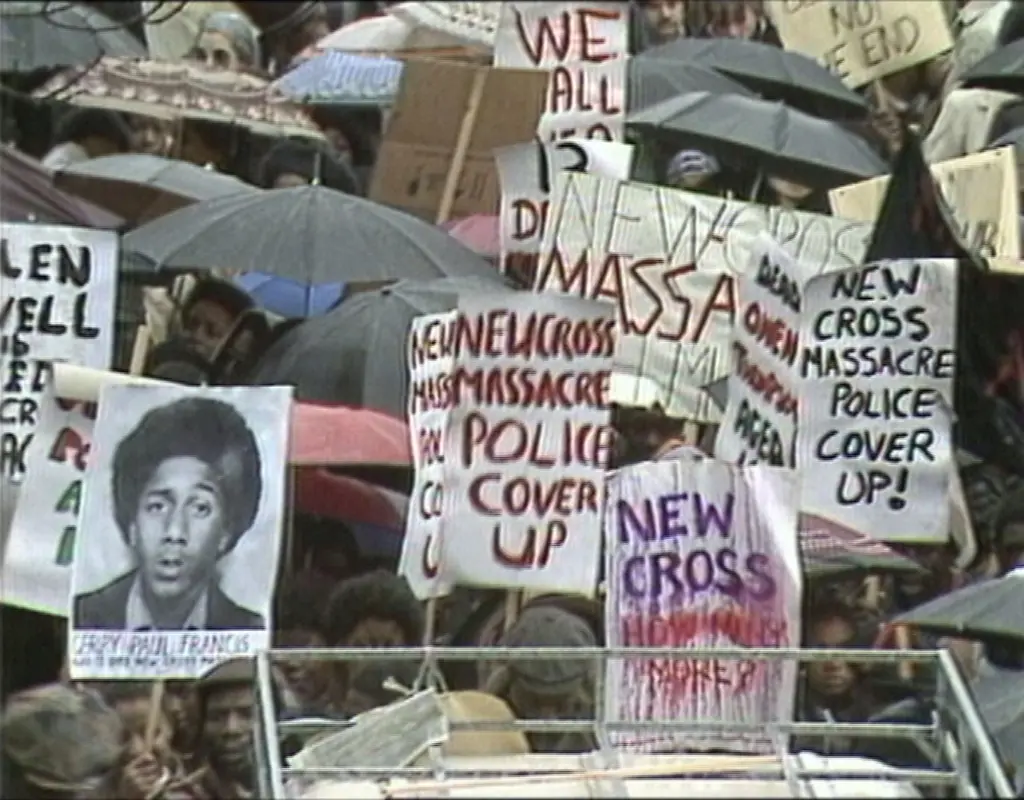

Little wonder that the Black community, in the words of the old slogan, get agitated, educated and organised. The Black People’s Day of Action on Monday 2nd March 1981 sees 20,000 people march through London. “The most powerful expression of Black political power that this country has ever seen,” says poet Linton Kwesi Johnson.

Marchers carry placards bearing the slogan “13 Dead, Nothing Said” and the faces and names of victims: all those we’ve already mentioned, as well as Patricia Johnson, 15; Patrick Cummings, 16; Humphrey Brown, 18; Peter Campbell, 18; Lloyd Hall, 20. With a heavy police presence, scuffles break out, leading to media coverage whose headline language is itself racist.

WAYNE HAYNES

The Sun: “Black Day At Blackfriars”. The Daily Express: “police injured in clash with demo blacks/rampage of a mob”. The Daily Mail: “6000 blacks in protest march.” The Sun again: “day the blacks ran riot in London”.

Racism rains from the top down. Uprising features news footage of Les Curtis, Chairman of the Police Federation at the time, denying that a policeman should be sacked if he calls someone the n‑word. He tells the interviewer that it’s a “matter of opinion” whether it’s an abusive term.

A month later, on 6th April, Operation Swamp – its name seemingly inspired by Thatcher’s inflammatory whites-first rhetoric – hits Brixton. Police pour on to the streets of the South London borough. They’re told: “If it moves, stop it and search it.”

Four days later, the Brixton riot explodes. Wayne Haynes, a man who knows of what he speaks, describes “good fires… fires of freedom. People were breaking the chains.” He certainly felt that sense of righteous revolt.

“I was an angry kid then. I had a whole future ahead of me. I was close to signing a pro contract to play football. I had so many other things on the line that I could have done. But it was all ripped away from me.

“On top of that, my girlfriend died. My closest friends died. And then my second love, which is music, has all gone up in smoke, everything altogether. I was an angry Black kid who hated white people.”

A month after the riots, the coroner’s inquest into the New Cross Fire opens. Outside, protestors mill with placards: “Blood a go run if justice na come”.

Denise has her day in court. The 11-year-old stands up and says, for everyone to hear, that no, she didn’t see a fight and that, yes, the police made her say she did. Sandra, meanwhile, is in hospital, giving birth to her and Paul’s daughter, Jeannine.

Eventually, after two hours’ deliberation, the inquest returns an open verdict. That is: no cause, no culprit and, therefore, no closure. Twenty-three years later, in 2004, the victims win a second inquest.

“The coroner concluded that the fire was probably started deliberately, inside the house, and not by a petrol bomb,” runs a postscript on Uprising. “Citing a lack of conclusive evidence, the coroner was unable to rule with certainty on the cause of the fire and returned another open verdict.”

Reflecting on those verdicts, Denise Gooding tells it straight.

“It’s as if we didn’t matter.”

STEVE MCQUEEN

None of this, insists Steve McQueen, is history, ancient or otherwise. He wanted to bring the story of the New Cross Fire, of the lives it cost and the repercussions it had, “into the present. Because if it’s not in the present, there’s no point in doing this.

“If it’s just about blowing off the dust from the past, it’s a relic. But these things are live and present as we have seen unfortunately with the events [sic] of George Floyd recently and Mark Duggan and so forth. So it’s up to us as filmmakers to haul this up to the public.

“Art is not a relic on a plinth behind glass or hanging on a wall,” he continues. “It’s about what it can actually physically do to change the narrative, to change the course of events in our everyday. That’s what Uprising’s about. It’s about making people think: ‘Hey, we can possibly do something. We don’t have to sit on our couches and take what’s happening to us. We can actually act and activate on what we see.’

“So in fact it’s a rallying call. That’s what Uprising’s about. It’s alive and kicking.”

It’s a sentiment Wayne eloquently echoes.

“I’m not looking for anybody to blame for the New Cross Fire. What I’m saying is, those of us who have been affected directly by the New Cross Fire, we need healing. And the only way for us to get that is to know that the New Cross Fire actually meant something.

“We know that the New Cross Fire was a catalyst for change in this country. Out of it came the riots, out of the riots came Scarman, out of that came change.

“But we’ve now come to a point where the changes we made back in the ’80s do not apply. We need some more changes to happen now before we end up with another revolution, ’cause that’s what happened in the early ’80s. We saw the power of the people in the ’80s. We need to use the power of the people for change now.”

As to why it’s taken four decades for this story to come to the screen, McQueen has a straightforward answer.

“The reason why this is only happening today is that we didn’t have the filmmakers because of racism – fact. The fact [is] that there were no Black people in film school… Don Letts wanted to be a filmmaker a long time ago but he didn’t have the opportunity so he was running around with a Super 8 camera. The reason why these films weren’t made [before now] is because… racism. Let’s not play! That’s it.”

Denise Gooding won’t disagree with that. I ask the mother-of-three how different she thinks things would have been if it’d been 14 white kids who died as a result of a fire at a teenagers’ house party.

“I think it would have been fully investigated,” she replies. “I don’t think they would have let it lie. I don’t think they’d have been forgotten the way we’ve been forgotten.”

What, I wonder, does Wayne Haynes – who still DJs, under the name Wayne Antoni, at parties and on various internet radio stations – feel whenever he hears that last tune he played on 18th January 1981?

“It’s really, really funny you ask that,” he replies, “because I played that tune two nights ago. And I got goosebumps. And I realised: I always get goosebumps with that tune. My body literally goes cold. And up until Thursday night [I didn’t realise].

“I met up with some of the other guys that were in the documentary on Thursday and when I came home, it was still rolling around in my head. On my computer I’ve got this folder that says: ‘New Cross Fire Music’. Every now and again, I go in there, take a few tunes out and listen to them. So I played Kingdom Rise Kingdom Fall on Thursday and it registered with me: that song was the point my life changed.”

Uprising is on BBC1 at 9pm on Tuesday 20th, Wednesday 21st and Thursday 22nd July, and on iPlayer