How Kris van Assche helped invent the modern man

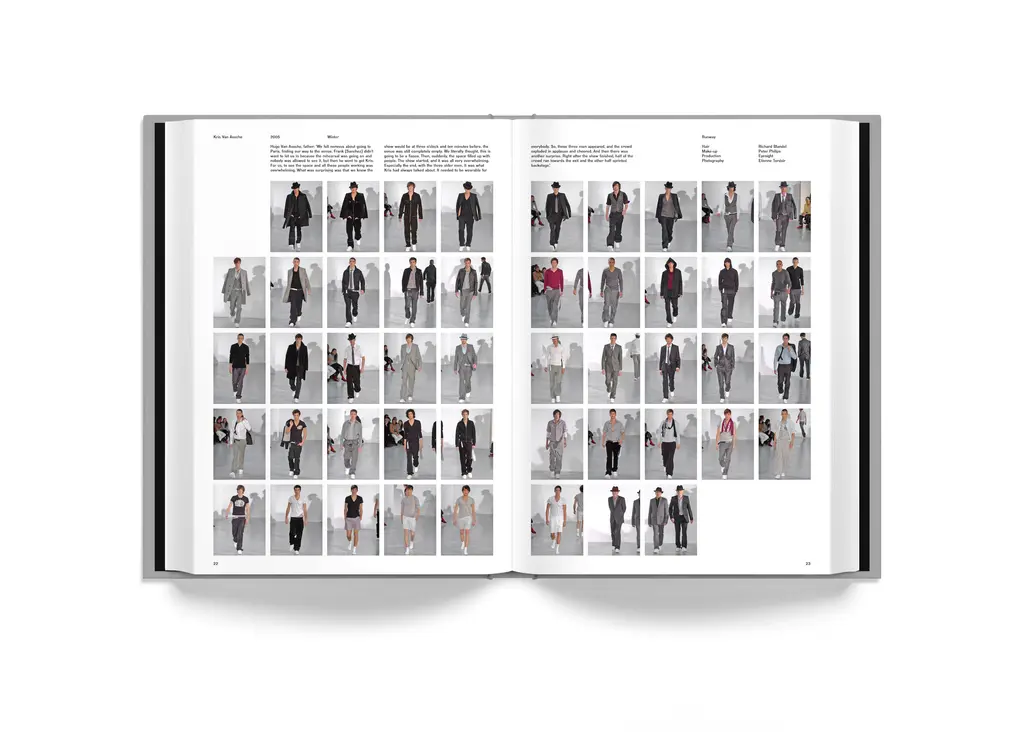

Dior FW15. Courtesy of Villa Eugenie

In the early-’00s, the designer introduced a romantic, vulnerable man to the runway. Now, in his new book 55 Collections, he’s taking some time to look back.

Fashion can be boring and Kris van Assche agrees. Sort of.

“So much effort goes into blending in,” the designer, 47, says. He’s FaceTiming from the home he shares with his partner in Paris, wearing smart, circular glasses, his hair neatly pushed back. Behind him, a selection of art, photography and fashion books are arranged on a shelf and, minutes into the call, we’re joined by his cat Frida (after Kahlo) who perches on his lap.

“It’s funny how there is so much conversation around self-promotion on social media, and yet there seems to be so many rules and codes. It’s funny how we celebrate self-expression, and then do everything in our power to look like the popular people on social media. We live in a very interesting time, but it’s not necessarily so beautiful to look at.”

There’s no better moment, then, for van Assche to look back on his greatest hits. For his first retrospective book 55 Collections, the Belgian designer has retraced the moments that have influenced him the most, from his childhood in the small town of Londerzeel and his years studying womenswear at Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts, to his tenures as creative director at Dior Homme, Berluti – where he has held the position since 2019 – and the launch of his own namesake label in between.

With photo contributions from the likes of Nan Goldin, Alasdair McLellan, David Sims and Willy Vanderperre, as well as editorials featuring Cindy Sherman, Lady Gaga, trilby-era Justin Timberlake and Beyoncé, 55 Collections is a detailed scrapbook documenting the life of a designer who helped reshape contemporary menswear in the ‘00s, a time when the industry was becoming stagnant.

Van Assche is far-removed from the celebrity status of designers these days. He has an Instagram account, yes. But beyond snippets from exhibitions he’s visited, holidays photos in Puglia and the regular selfies he takes in front of the same mirror while holding a new bunch of flowers, van Assche has, by his own admission, kept himself to himself throughout a career spanning over two decades.

But just a page into 55 Collections and van Assche is at his most intimate, opening with a picture of him as a young boy at his first communion in 1982. Then: a scan of his student card, him and his mother on his 18th birthday, a newspaper clipping of the Academy’s new batch of fashion graduates (“Antwerp’s Cradle of Design”) in 1998 and, in the same year, a photo of himself at Antwerp Zoo wearing a slick leather jacket. Each image reveals small signs of a designer who, early on, “realised that clothes did not just grow into your closet, but that somebody was actually designing them,” he says. “I wanted to be that person.”

1998 press clipping graduation show

Van Assche knew from the offset that he’d need to open up more to make the book. “I’ve given a billion interviews, yet people think I’m quite reserved. My partner said, ‘If you’re going to make this book, then you need to give a little bit more than what you’re used to giving,’” he says. “And so this is why the book starts here. This is beyond a collection – it’s basically about 20 years of my life.”

In 1998, having just graduated from the Academy, van Assche interned at Yves Saint Laurent for four months, and soon became an assistant to Celine’s current creative director, Hedi Slimane, for the French house’s ready-to-wear menswear line, Rive Gauche Homme.

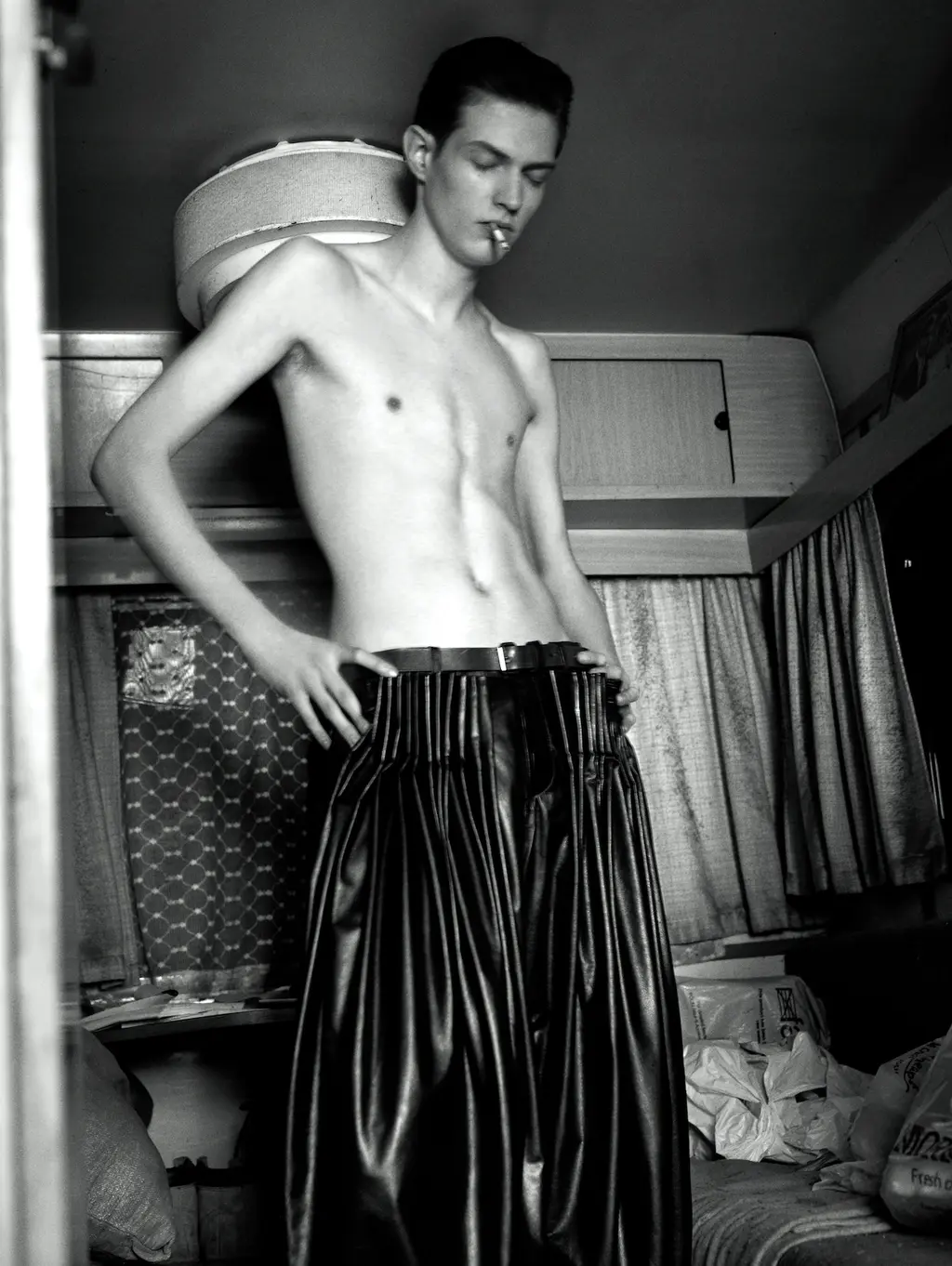

When Slimane moved to Dior to launch its Homme line in 2000, he brought van Assche along. Slicing through the baggy, ill-fitted tailoring popular in menswear at the time, came Dior Homme’s razor-sharp tailoring, skinny silhouettes and the smoky allure of its boys irreverently strutting down the runway with a lick of eyeliner on.

Far from Versace’s ripped, Zeus-like figures of masculinity, or the grungy nihilism of Calvin Klein, Dior Homme celebrated the full emotional spectrum of manhood. It made clothes for young men who weren’t necessarily performing centre-stage, but were out somewhere in the crowd on a first date, smartly dressed and unafraid of their vulnerability. Hyper-masculinity was being challenged; six-pack abs, a golden tan and chiselled jaw suddenly felt like an outdated ideal.

Van Assche left Dior in 2004 to set up his own namesake label and, through 20 seasons, the designer continued to subvert everyday menswear with smart sensuality. Crisp white shirts poked out under short-sleeve black T‑shirts, silhouettes were almost robotic in their clean precision, and tailored trousers, which up until then had been typically reserved for evening-wear, replaced jeans, worn with everything from parkas to knits. Van Assche wanted his men to revel in refinement.

“I’ve always liked the idea of making an effort,” he says. “My grandma used to tell me that dressing up and looking good was a form of politeness. That when you feel miserable, there’s no point in putting that on everybody else. You don’t need to share your misery – just dress up and look good.

“Obviously that’s a bit over the top,” he continues, laughing at his grandmother’s schooling. “But when you go on a first date or take your partner to the opera… All these stories I’ve told in past collections have been about dressing up for that occasion. You feel special when somebody makes an effort.”

DIOR FW08 editorial. Photography David Sims, styling Joe McKenna.

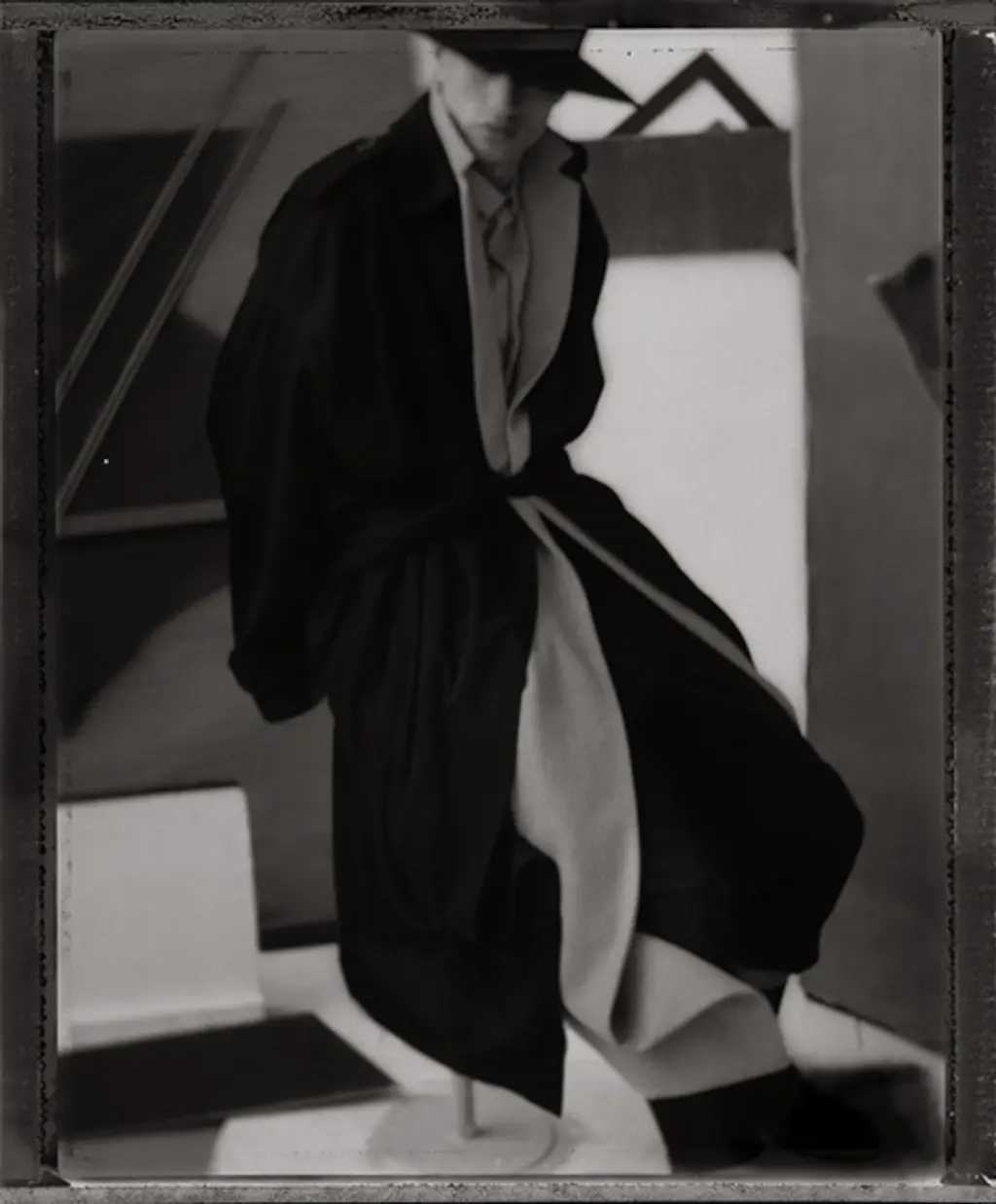

DIOR FW10. Editorial by Sarah Moon Styling Mauricio Nardi

In 2007, van Assche succeeded Slimane as Dior Homme’s new creative director, bringing with him notions of classic, old world beauty that his grandmother – a recurring figure in his influences – taught him early on. “I was looking for more beauty and sophistication. Of course, when you’re a teenager, the two don’t go so well. But that’s what I’ve always been looking for,” he says. Does that mean he was a rebel as a teenager? “A polite rebel.”

Even now, after ascending to the top of the fashion industry, he looks back on those days as some of the “best years of my life”. Once he started at the Academy, he left the conservative town he grew up in and immersed himself in a crowd of like-minded artists and photographers who came together to work hard in the studio and, come midnight, venture out into Antwerp’s clubs.

At uni, tutors would often tell students to loosen up, let go and “be more crazy,” remembers van Assche. “Which is funny because, 25 years later, that is still something that you might read in one of the reviews of my work,” he says, perhaps referring to critics who haven’t always been supportive of van Assche’s case for suiting. But even though he has a soft spot for tailoring his designs have always been grounded in reality, influenced by the workwear uniforms he grew up around, the music scenes he was immersed in as a student and, in every single one of his designs, raw emotion.

“I’ve always affirmed that I want my clothes to be worn in the streets, which doesn’t mean that they need to be basics,” he says. “That is something very present in today’s fashion – either there are these incredible conceptual statements, or people say they want to dress people, and then make basics.

Dior FW16, Willy Vanderperre Larry Clark

“My aim, and it’s not for me to judge whether I’ve succeeded, has always been to be right in the middle trying to make wearable clothes that have a good dose of creativity.”

Through his work at Dior Homme, Berluti and his own label, over the years, the van Assche man has become a recognisable figure: V‑necks, low-slung trousers, trilby hats and suspenders have all infiltrated the cultural zeitgeist at some point over the years.

Along with Hedi Slimane, he helped amplify the indie scene’s popularity in mainstream menswear in the early-’00s; you only needed to walk past a Topman to have seen van Assche’s influence in the high street store’s shop windows. Young British boys suddenly began working with their bodies, rather than hiding them under swathes of fabric, and the sartorial codes of masculinity and femininity were slowly beginning to blur, some 20 years before the progressive fluidity we’re seeing on runways now.

“Men tend to want to belong to a group, be that political or football or a street style. Men get into these clans and they kind of stick to the rules and the codes, and they feel very comfortable when they’re part of a clan,” van Assche says. “I’ve always loved messing around with those codes and combining elements which you were never supposed to combine. The more there are rules, the more it’s fun to push them a little further.”

Van Assche was one of the first contemporary designers to encourage young men to ditch the unflattering jeans and scrappy, oversized T‑shirts, and adopt a style that befits the modern man: romantic, vulnerable and unafraid to explore sexuality. Today, his influences can be found in the work of emerging British designers such as Aaron Esh, Luke Derrick and recent Central Saint Martins graduate Max Foucaut.

So, does Kris van Assche really think fashion is boring these days?

“There are independent voices out there that really interest me,” he says. “So let’s try not focus on these big situations that try to invade our minds, and let’s also leave room for the smaller brands. Because a lot of people are actually making an effort!”

In a suit, no doubt.