The queer artists taking over Art Basel Miami Beach

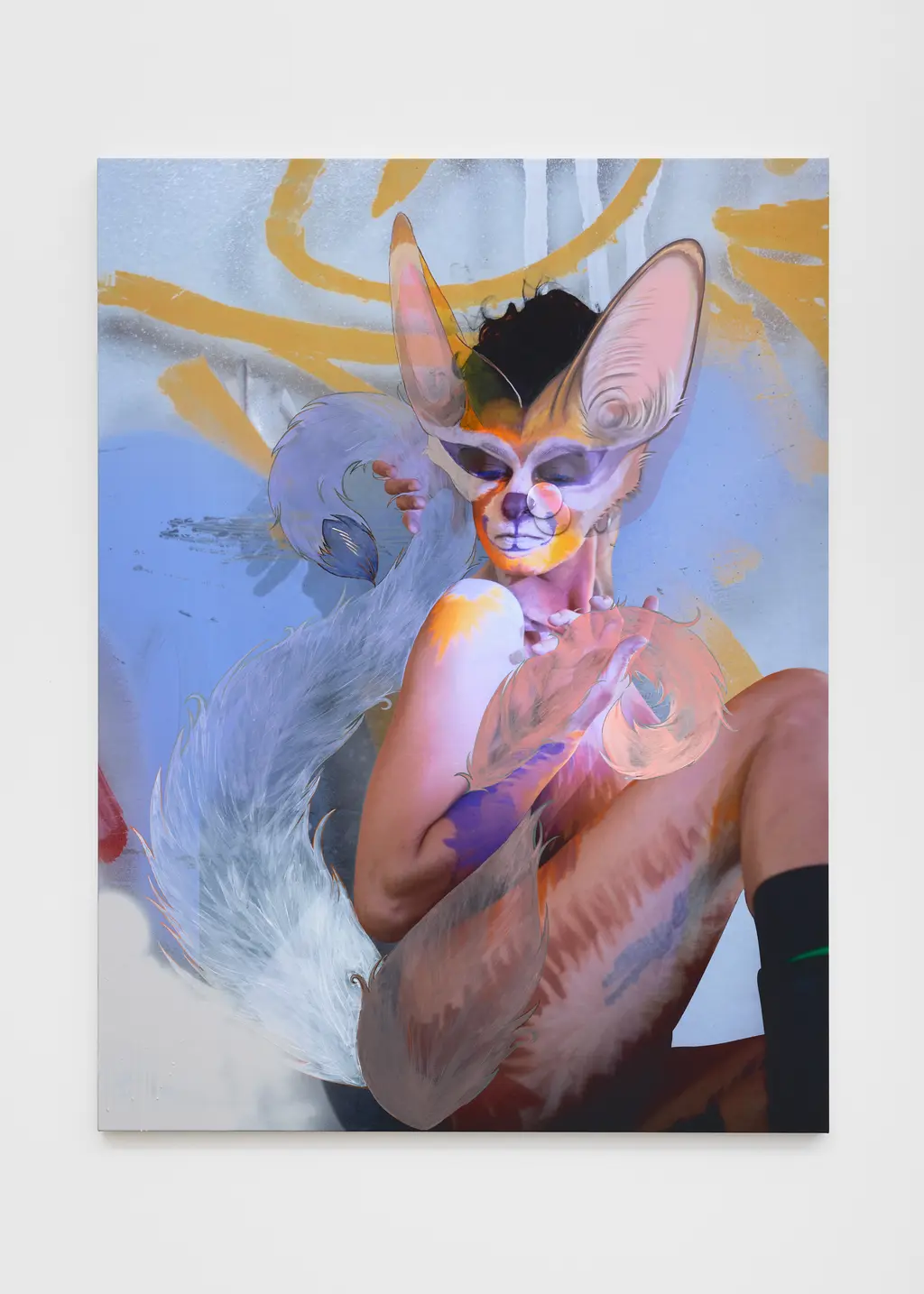

Juliana Huxtable

It’s no secret that Miami Beach is queer as folk. Aside from legendary gay bar Twist, Gianni Versace’s mansion and the year-round display of speedo-clad himbos, this month the city is home to many new queer art exhibitions.

Culture

Words: Joe Bobowicz

Welcome to the world’s glitziest (and campest) art fair: Art Basel Miami Beach. Hot on the heels of Art Basel Paris, this year’s Floridian outing promises a sizeable contingent of historical and contemporary queer art, spanning surrealist, non-binary artist Claude Cahun all the way through to radical trans collagist Ebun Sodipo.

Of course, where there’s an art fair, there’ll be queer representation in 2024. In this spirit, Art Basel has put its Nova section to good use – here, emerging galleries focus on new work from up to three particular artists – spotlighting everyone from the Olly Shinder-modelling artist Michael Ho, to Tumblr heroine-turned-radical-art-DJ Juliana Huxtable, whose name you might recognise from Berghain or the cooler dance festival line-ups.

Elsewhere, a section called Survey hones in on pre-millennium works that bear newfound relevance today, such as Claude Cahun’s. The Kabinett section offers blue-chip galleries an opportunity to dedicate part of their booth to a specific showcase, such as PPOW’s focus on Manuel Pardo, the gaudy gay obsessed with elaborate depictions of his mother and flowers.

As the dust settles in the art world following Dean Kissick’s viral lament – “descriptions of work are dominated by the language of decolonial or queer theory,” he moans – we’ve doubled down on the latter. Sorry!

Tellingly, Wendy Olsoff, the co-founder of New York stalwart and underdog champion PPOW gallery sits on the board for Art Basel’s Miami Beach selection committee. If that means buyers such as Bernard Arnault or François-Henri Pinault pick up a brick-worked cock painting, then so be it. Miami is here and queer for the foreseeable. These are just some of the names to look out for…

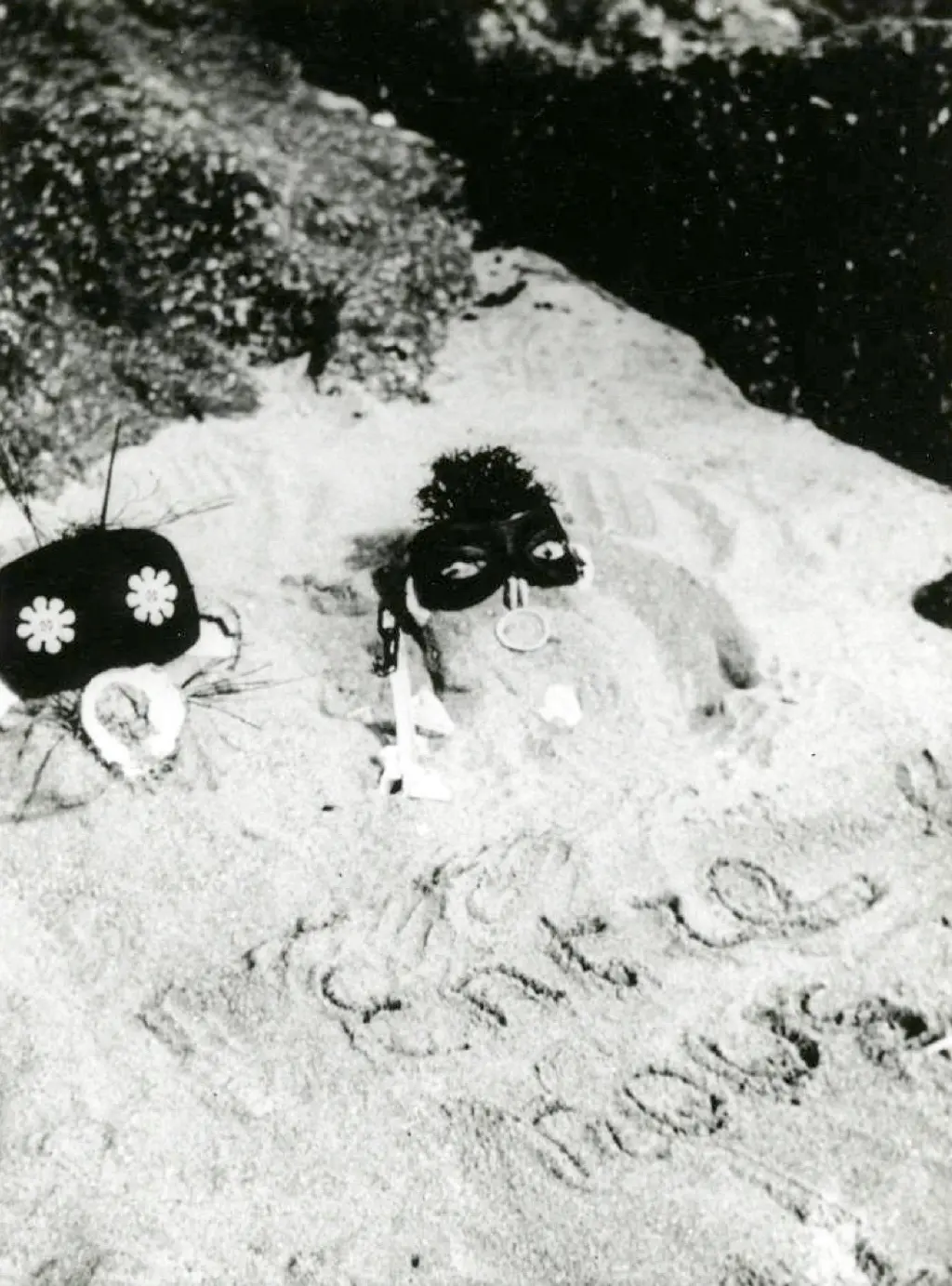

Claude Cahun, Galleria Alberta Pane

Long before terms like “non-binary” or “gender-neutral” were part of our lexicon, there was Claude Cahun. Born in 1894 in western France, Claude was lover to her stepsister, Suzanne Alberte Eugénie Malherbe, who adopted the pseudonym Marcel Moore. Together, Claude and Marcel became artistic collaborators, working closely on many of Claude’s surrealist projects in photography, literature, collage, sculpture and performance.

Claude studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris, while Marcel took painting and drawing at the Fine Arts Academy in Nantes. Eventually, they both wound up in Montparnasse during the ’20s and ’30s, a bohemian spot on the Left Bank, serving as two renegade figures in an otherwise heteronormative, patriarchal surrealist scene. In 1937, they fled to Jersey Island when the wartime climate became untenable.

There, the pair set up a Nazi resistance, flyering the island with their infamous publication, Der Soldat Ohne Namen (The Soldier with no Name), an anti-nationalist call to arms of poetry, skit-like conversations and photo-montage, targeted at German soldiers on the island. Both sentenced to death but freed when the war finished, they lost a large portion of their work due its perceived obscenity.

In Claude’s works, they experiment with aesthetics, displaying themselves in myriad guises. In some instances, they’re hyper-femme, as in Claude Cahun et Roger Roussot dans Barbe-Bleue de Pierre Albert-Birot (1929), while in others, they’re a living, breathing proto-dyke, clad in blokey, ribbed tailoring (Autoportrait devant les affiches de Geo Dorival, 1911).

Ebun Sodipo, Soft Opening

After spending nine years of her childhood in Lagos and two in Abuja, artist Ebun Sodipo came to London in 2004. Her parents both worked, so her grandmother and cousins spent a lot of time caring for her, introducing the artist to bible stories and West African mythology.

“I suspect these stories influenced how I see history now: as stories and narratives disseminated by a particular power structure, concerned only sometimes with ‘fact’,” she explains. “My upbringing was very religious. Both my parents were leaders in the Redeemed Christian Church of God, and yet they combined this colonial way of seeing the world with some traditional religious practices, such as belief in babalawo [Yoruba healers] and witchcraft.”

Ebun’s practice – which spans collage, performance, installation and poetry – owes a lot to the syncretic nature of her family’s faith, which she applies to her own Black transness. In this vein, she takes inspiration from varied sources – be it Yoruba culture, old Naomi Campbell moments (I worry that you’ll work in an office, 2024) and even vlogs of hair-braiding clips (Illustrations for Libations, Attestations, Affirmations, 2020) – to give found imagery and phenomena new meanings. Her assemblages, pulled together with printed paper and mylar, sealed in epoxy resin, serve as what she calls, “survival strategies of the marginalised, particularly the uses of anger and memory”.

Having shown with some of London’s cutting-edge galleries, including Neven Gallery and VO Curations, Ebun recently took to LA for a solo show with Soft Opening. Throughout her work, she merges imagery from online – often social media – to build an archive for trans women of the future. Subtlety reigns supreme for Ebun, whose practice never gives itself away on first viewing.

“I think people expect a kind of [spectacle] with my work, and the work of POC people in general, that I deliberately avoid,” she says.

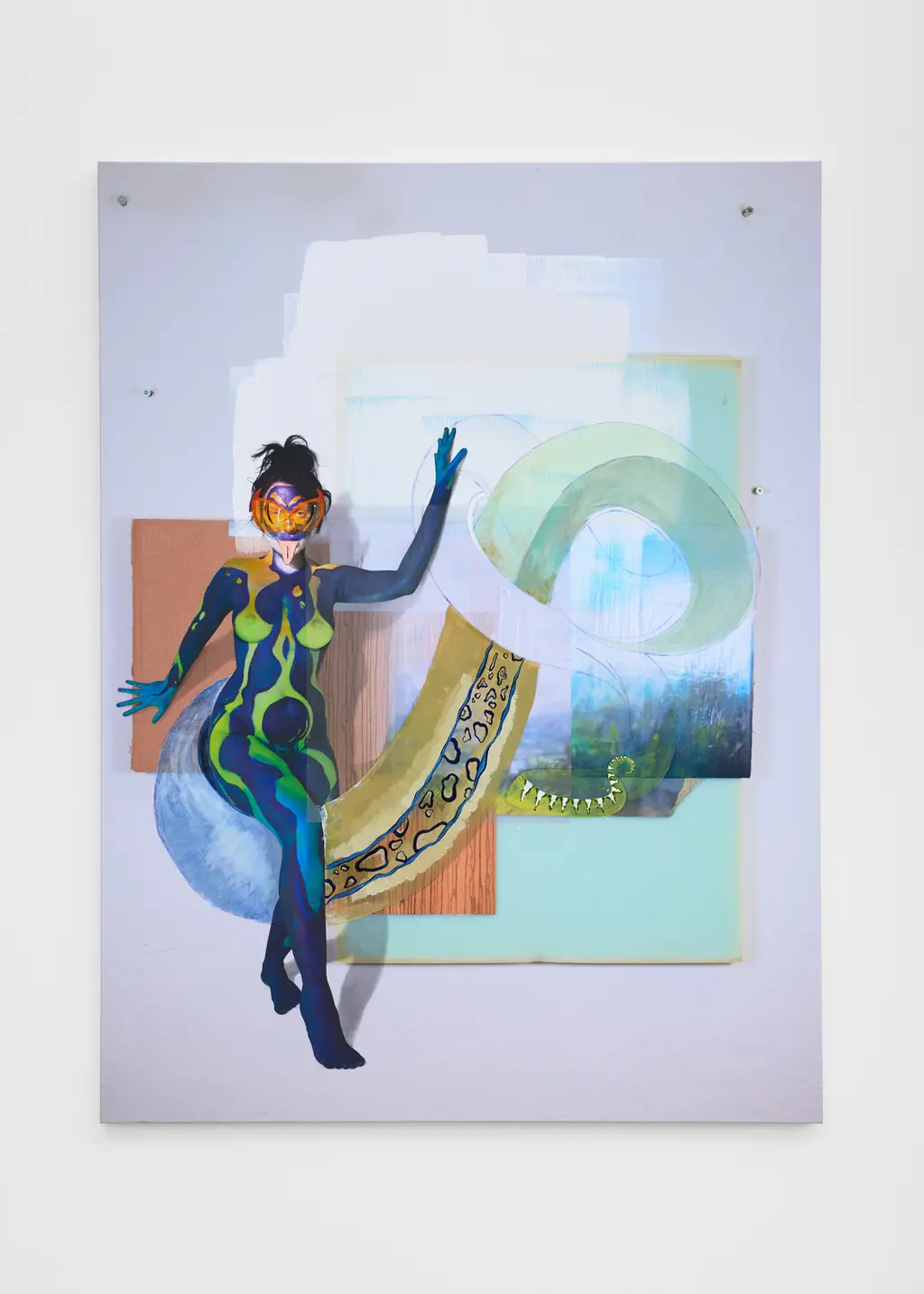

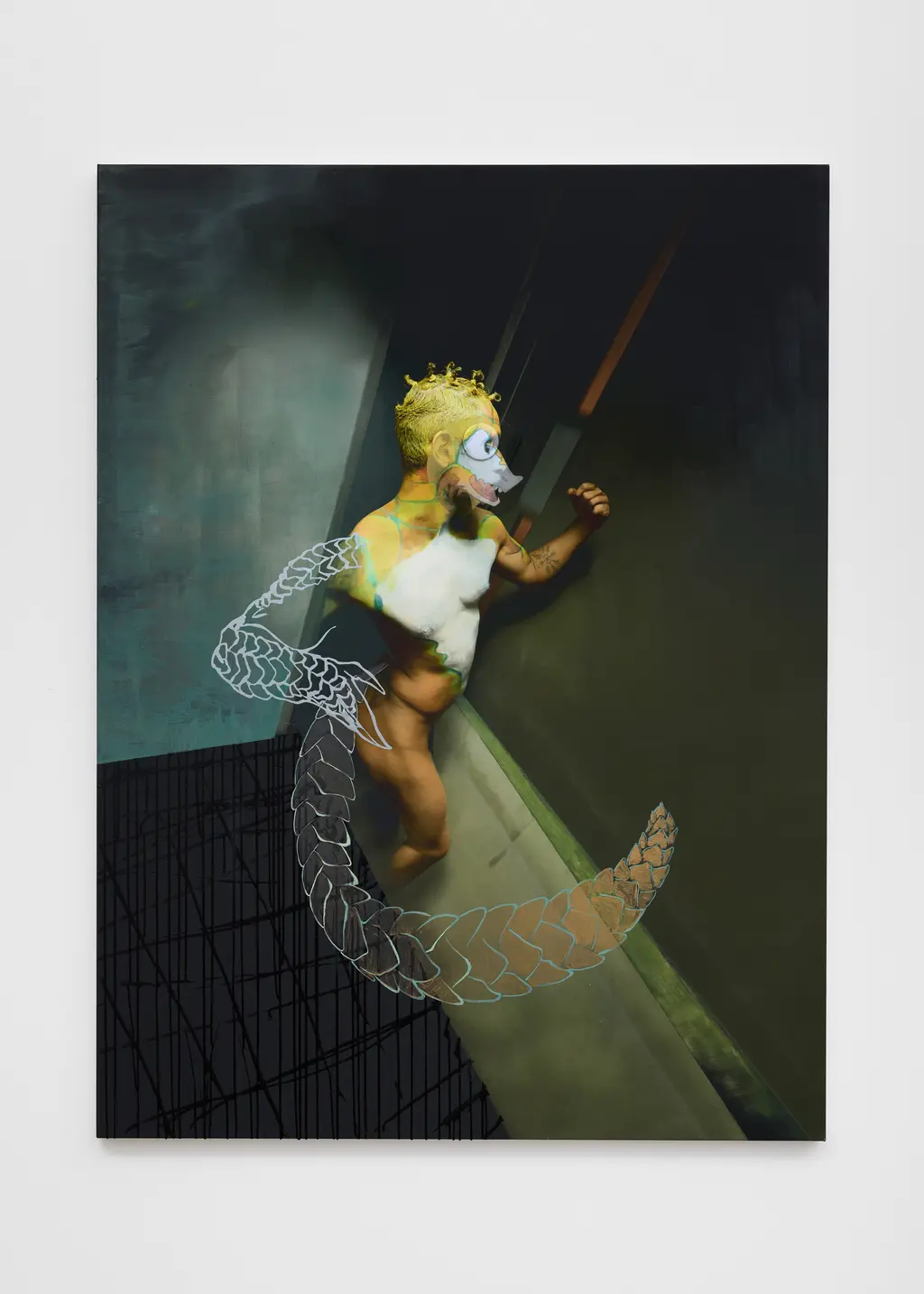

Juliana Huxtable, Project Native Informant

Born and raised in Texas, Juliana Huxtable has lived several lives. During her days studying at Bard College, she became part and parcel of the House of LaDosha, a New York post-ballroom troupe. She’s also a co-founder of nightlife outfit Shock Value, where she’s programmed some major parties. Add to this copious amounts of clubnight and festival slots, and you’d be forgiven for wondering how she finds the time to make art.

Juliana is big on a process known as “-ussification”, an idea born from slang, where all and one can become a pussy in an act of reclamation, popularised in 2021 on TikTok. What’s that? Essentially adding “-ussy” to the end of any otherwise plain word.

More broadly, post-human sensibilities define her work, not least furry aesthetics. Her recent show in London, HEADS & TAILS IN THE STRUGGLE FOR ICONICITY (2024) at Project Native Informant presented arthropodic (ATHRO ANARCHY, 2024), tailed and amphibious (SKINKISM, 2024) or avian (PANGS, 2024) creatures. For her presentation at Miami Art Basel, she expands on this same body of work.

“They are fursonas developed with my friends that I then elaborate in the process of building each portrait,” explains Juliana. “They begin with conversations where we figure out what the appropriate fursona is, then I paint and shoot them, and the process of building the portrait – in printing, drawing, painting – is one of elaborating them into an inter-species, multi-medium, painting-collage.”

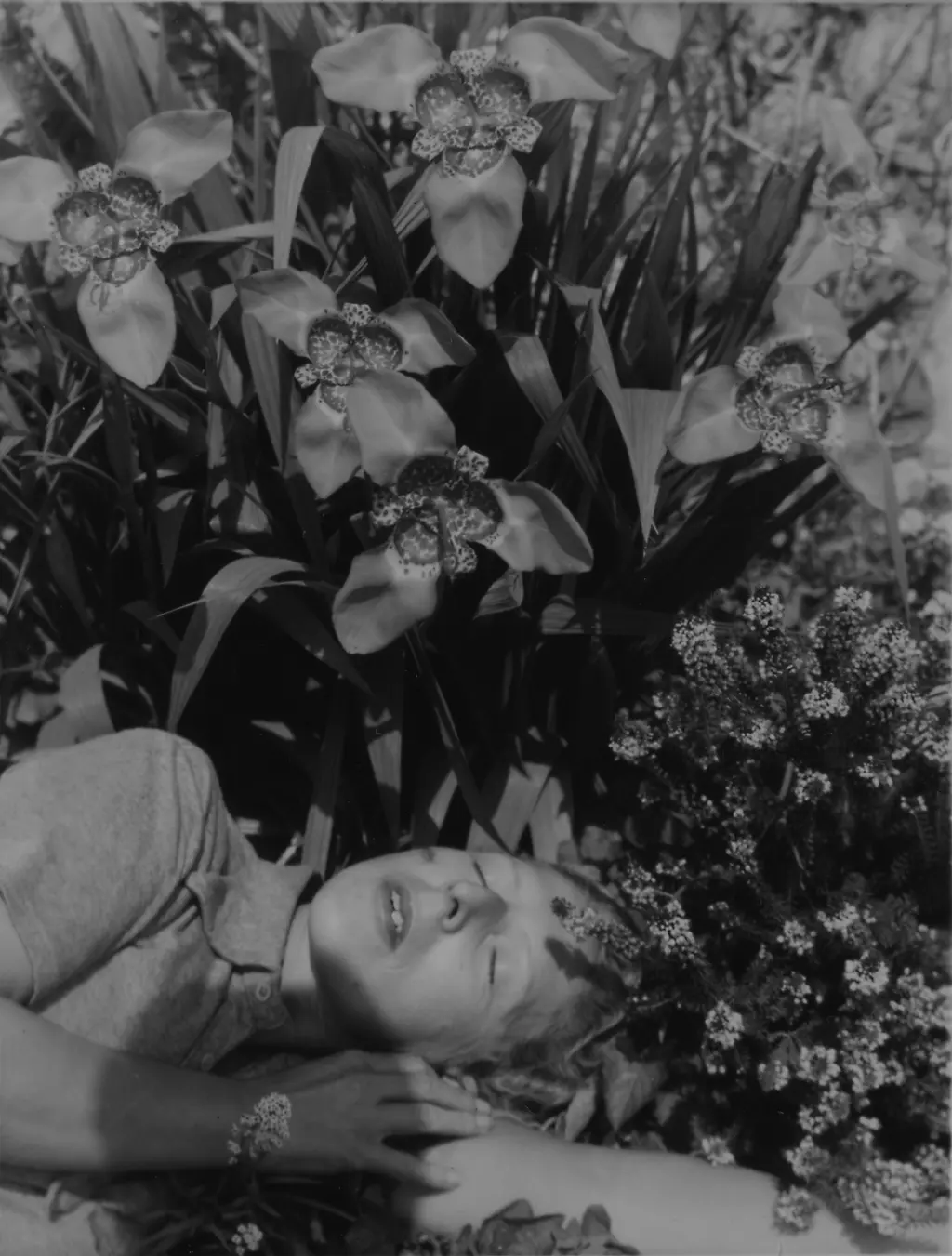

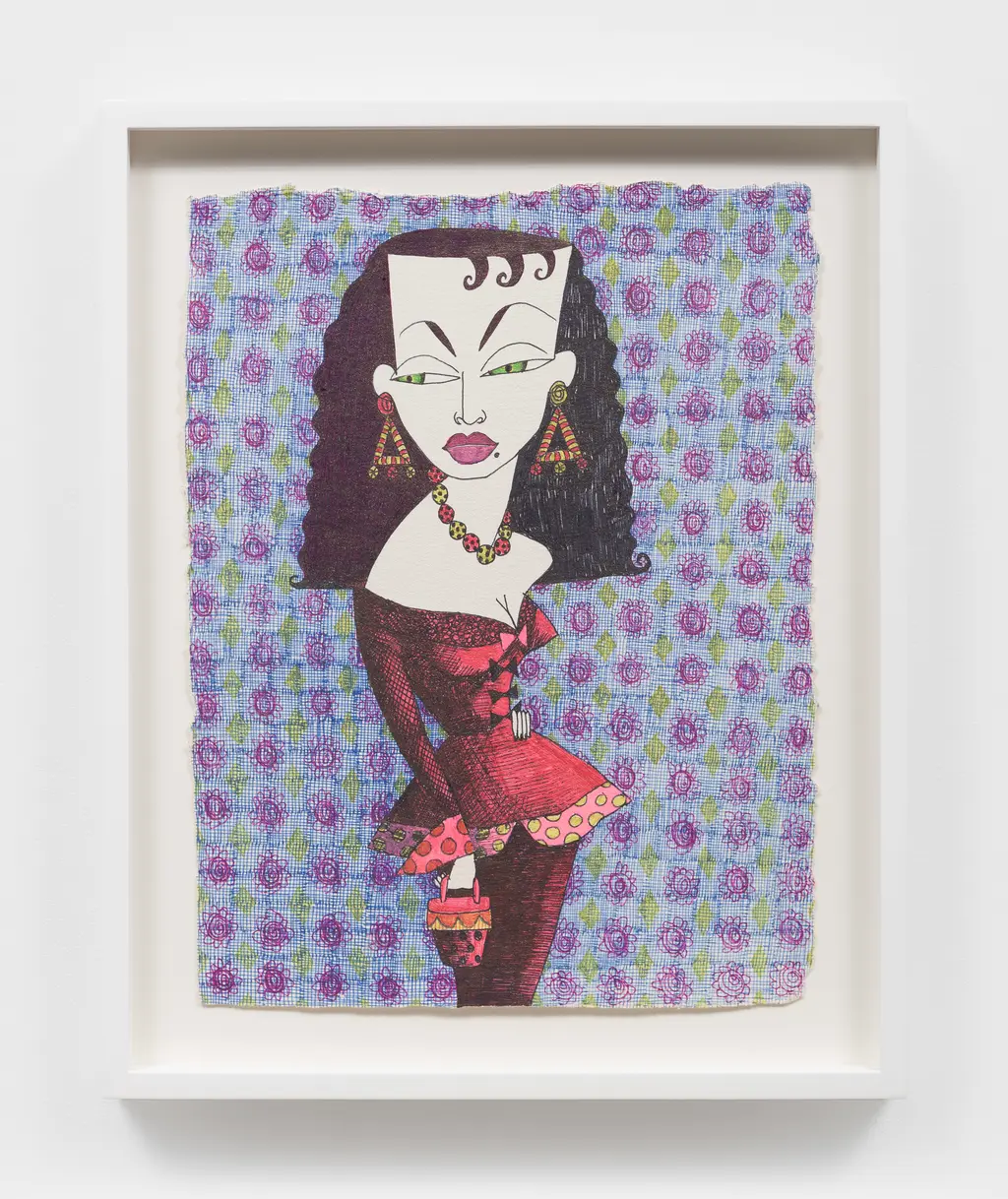

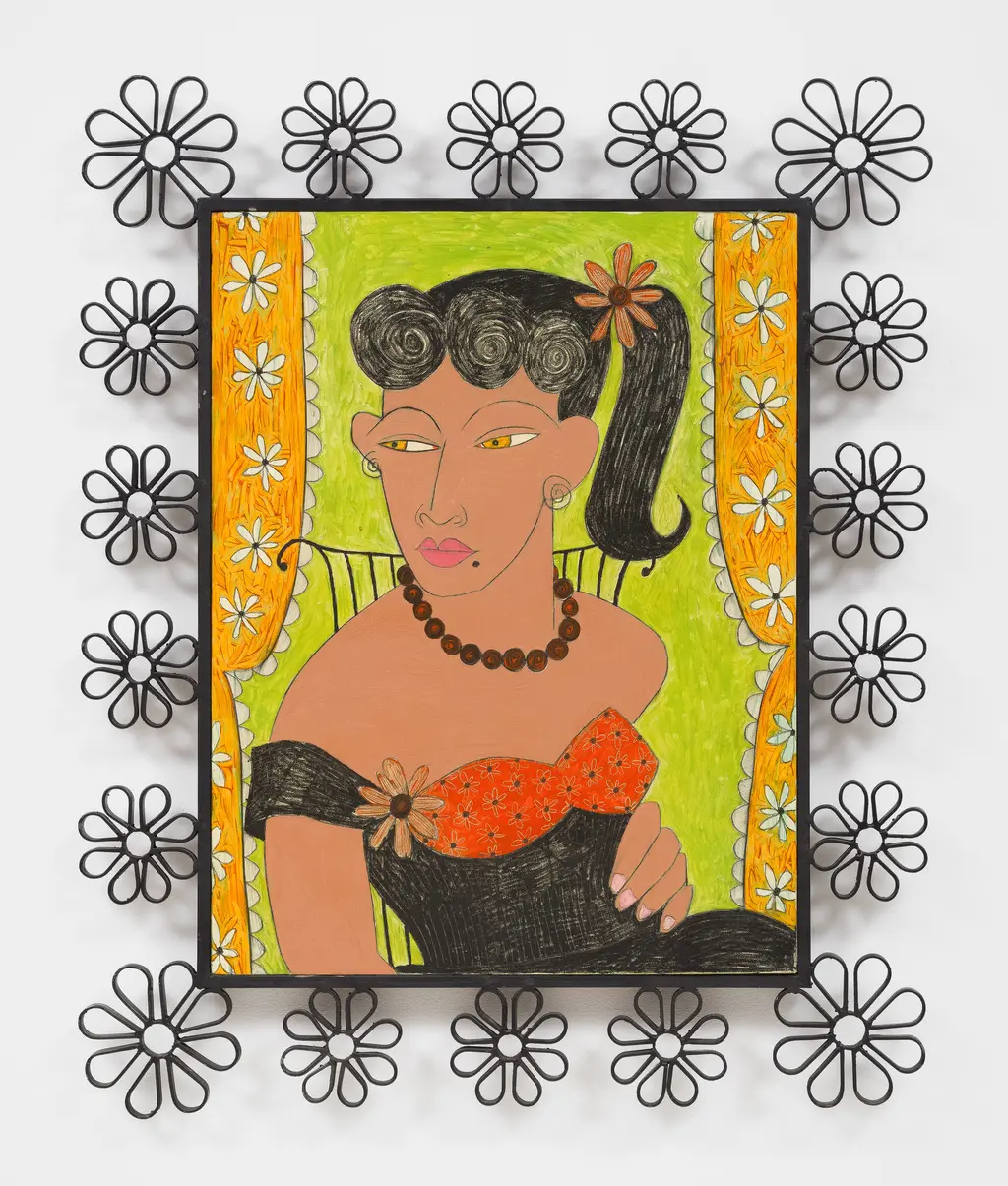

Manuel Pardo, PPOW Gallery

A vision of camp, the late Cuban artist’s paintings – delicately lined and blocked-out in brash tones of cerise and fuschia – riff on stereotypes to present something highly stylised, albeit cartoonish. The thinking went that, if gay men are clichéd for their dedication to women as hairstylists, designers or make-up artists, then Manuel would up the ante, embracing his status as a mummy’s boy.

Across his works, his mother Gladys is reimagined in dollface dresses, complete with sweetheart necklines and fifties patterns – polka dots (Untitled, Stardust, 2007), daisies (Untitled, Stardust, 2006) or dainty florals (Mother and i in Technicolor, 1995).

Manuel – who passed away in 2012 – and had spent years living in New York as a respected artist, was an easy fit for PPOW given the gallery’s USP of showing 20th century New York art.

“While there are obvious ties to artists like David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong and Hunter Reynolds in terms of the radical portrayal of queer fantasies,” Wendy Olsoff says, “Pardo’s work goes beyond the obvious, as he was an artist who was primarily fixated on imagining alternate universes that function as doubles for our present time,” she adds.

Looking at Manuel’s wider works, you’ll also notice motifs specific to his life experiences as a gay man living through the AIDS crisis. “It was Pardo’s decision to focus his attention and career on envisioning lush alternate worlds, while still encouraging realistic safe sex practices through his imagery, that made his response to the epidemic so singular,” says Isaac Alpert, PPOW’s director of estates.

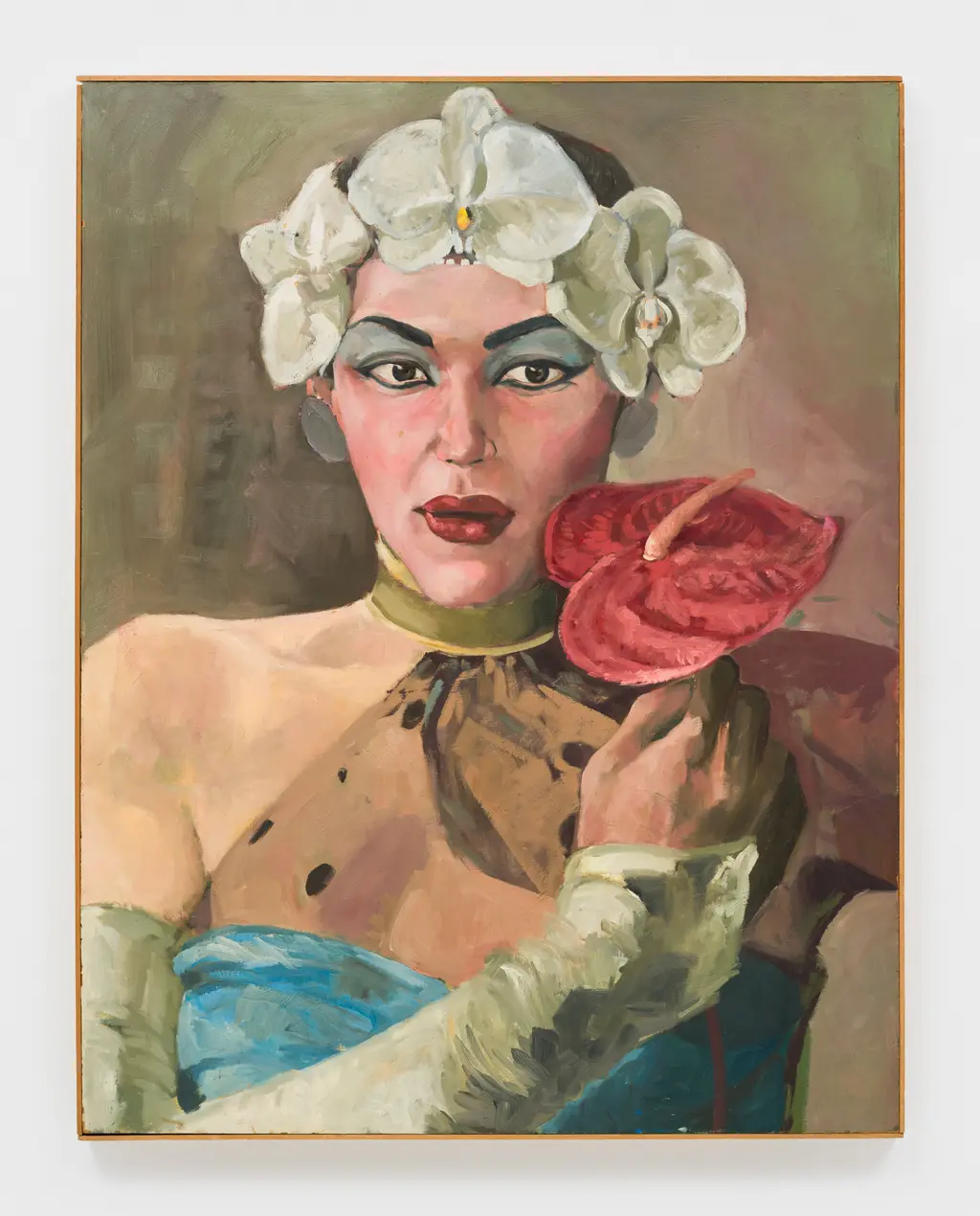

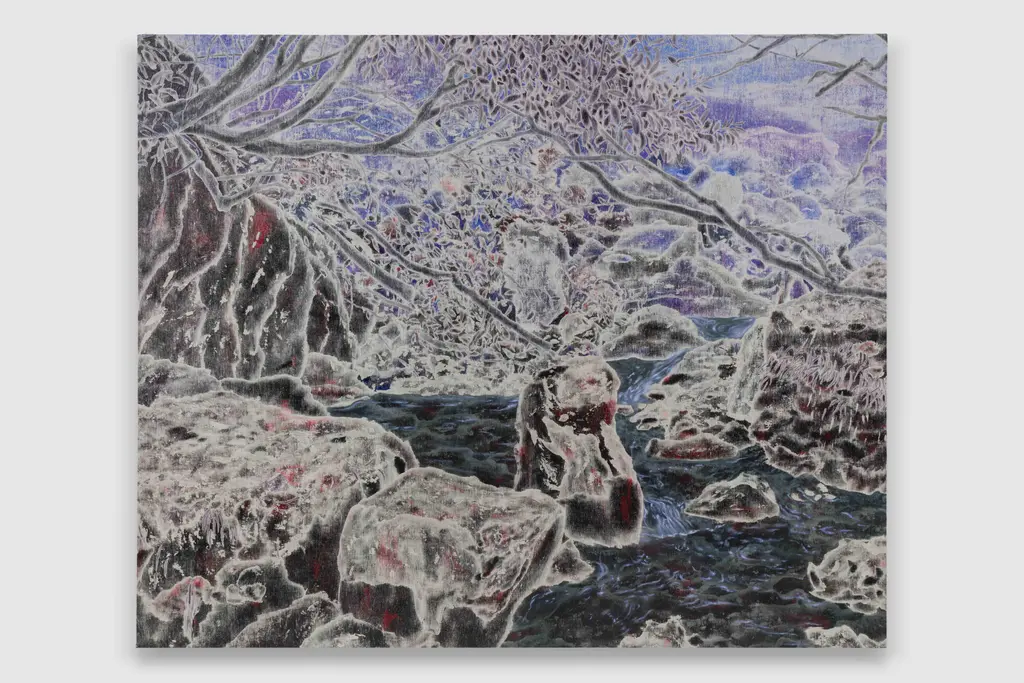

Michael Ho, Gallery Vacancy

Chinese, German and Dutch artist Michael Ho, who you might recognise from Olly Shinder’s SS24 runway show, graduated from the Architectural Association in 2019, carving out his status as one of the most intriguing painters coming out of London right now. Previously working with his late, great collaborator Chiyan Ho, who passed away in 2022, Michael has continued a legacy the duo built together, crafting otherworldly scenes, or realms, that are both obscure and lush.

Across Michael’s works, themes and motifs range from public parklands – sometimes, cruising sites – through to Chinese mythology and outdoor jungles. Whether it’s a leather jacket peeking beneath the foliage (Before You Decide That I Am a Saint, 2023) or a dreamy encounter between two men (History Will Wait for Us, 2023), Michael’s works pulsate with energy, enhanced by details: forearms lined with indigo veins, illuminated cigarette billows and refracted surfaces, for example.

For Art Basel Miami Beach, Michael presents similarly murky non-spaces, studying the cartographies and visions depicted in traditional shan shui (山水) paintings – think spellbinding rivers, mountains and waterfalls – and translates these to build his own environments.

“I hold a Dutch passport, but can’t even speak Dutch. So what does it mean? For me, home is in a state of flux, and of course this doesn’t exist as a real place, hence why I am trying to visualise it – a place where borders dissolve and cultures mix,” he adds.

The mottled, microbial sensibility of Michael’s canvases’ backgrounds deserves special attention. “All my paintings start from the back side of the canvas from which I layer and push paint through,” Michael says Michael. “It was all a happy coincidence quite frankly.”