Daniel Craig and Queer: the spy who loved him

Ahead of a Q&A and special FACE screening of Luca Guadagnino’s scorchingly sensual film, its leading man talks orgasms, Oscars and iPods.

Culture

Words: Craig McLean

He’s here, he’s Queer, get used to it.

Daniel Craig’s new film is Daniel Craig like we’ve never seen him before. Not even his rackety young lover of Francis Bacon in Love Is the Devil (1998), or his confused young lover of a much older woman in The Mother (2003), come close. As for Bond?

Bond who?

In director Luca Guadagnino’s grimy, trippy, sweaty and sexy adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ novella Queer, Craig plays Lee, a version of the author. He’s an expat American adrift in Mexico City in the early 1950s. Living fast and loose and high, he falls in love-and-lust with Allerton (Drew Starkey), half Lee’s age, give or take, and recently discharged from the US military.

It’s an obsession that sends both men on a dangerous spiral through the streets of the Mexican capital and the jungle of South America. A soundtrack of Prince, New Order and Nirvana – not to mention his co-star Lesley Manville wearing a freaky mask pulled from a JW Anderson pandemic-era fashion show – amplifies the feeling of vivid, visceral, chaotic connect/disconnect. As Craig has put it, Queer is “not a story of unrequited love, it’s a story of an unsynchronised love”.

The Cheshire-born actor, 56, leads from the front, burning up the screen with a blurring incandescence. Lee is an elegant but disintegrating wraith dressed in authentic period suiting (and underwear) dug up by the film’s costume designer. He’s the aforementioned Jonathan Anderson, who also dressed the game-set-and-matchless love triangle of Zendaya, Josh O’Connor and Mike Faist in Challengers, Guadagnino’s other 2024 film of tortured passion.

Ahead of this week’s special London preview screening – hosted by THE FACE in partnership with MUBI – and our accompanying onstage Q+A with Queer’s leading man, we had pre’s with Daniel Craig last week.

This interview has been edited for clarity, length, Craig’s swearing (his, not mine) and to lose that bit where he called me an arsehole (in a nice way).

Congratulations on the film, Daniel, an absolute triumph. I’ll blow more smoke up your arse in public at our screening.

People will pay good money for that!

I’ll begin by reading you a quote from your director, Luca: “Lee, before becoming the iconic Burroughs we know, is a kind of dishevelled, childish man.” Can you unpack, please, this idea of Lee as a dishevelled, childish man?

He’s all those, but he’s also the guy walking around the street in slow motion to Nirvana with a gun on his hip. There’s that going on as well. There’s a mask of masculinity around him that he swaggers around town [in]. And then suddenly he’s [acting like] a teenager in a bar, there’s a guy across there that he very likely is falling in love with… and he’s fucking up!

That is just so human and recognisable to me. So I think that’s the child [element]. In a way, he’s younger than Drew’s character. Allerton’s a steady, mature human-being. It’s Lee that’s the one that’s going through puberty.

You’ve said that, once you read Burroughs’ book, it was a “really easy decision to do the film”. Why did reading the novella make it a no-brainer?

Actually, I read the script and the book at the same time because the book is literally an unfinished novella. So it’s a very quick read, and I read them both in one evening. The script sticks quite religiously to the book, apart from the final section, which is the trip and the finding of the Ayahuasca.

Dr Cotter in the book is a guy and blankly refuses them any Ayahuasca. So the book doesn’t fizzle out, but it doesn’t end in a satisfactory way. And Luca was very keen that we saw, in the movie, a moment where [Lee and Allerton] really did come together…

Then casting Lesley Manville as Cotter, changing the gender, and making it a more motherly part – someone who was taking care of them and actually encouraging them to go on this journey – felt [like] it had a much more emotional impact than the book maybe has.

“That was Drew and I’s first introduction: getting into a room, stripping down to tights and rolling around on the floor! Which tends to break the ice”

In his introduction from 1985, for Queer’s long-delayed publication, Burroughs wrote: “The book is motivated and formed by an event which is never mentioned, in fact is carefully avoided: the accidental shooting death of my wife, Joan, in September 1951… I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death.” How did that knowledge inform your understanding of the character of Lee?

We threaded it in. There’s a couple of moments: in the tripping sequence at the end of the movie, and there’s a moment in a room where two people are playing at William Tell, because it’s how the [real-life] tragedy happened. They were on a lot of drugs, I think, both of them.

[Professor and author] Oliver Harris is the foremost expert on Burroughs, and we talked to him a lot before we started filming. He said: “Look, it’s all in his imagination. And it may be that a lot of Mexico City, a lot of the bars, a lot of the situations, are from other events in his life.” So as far as I’m concerned, this isn’t Burroughs. This is a construct of Burroughs.

So we wanted to make sure that we paid homage to it in the movie. But it’s not the driving force of the movie, the massive, tragic event that it was.

You and Drew have to go deep, and go together. How was he as an acting partner?

I mean, magic. We met up about two weeks before shooting. The Ayahuasca trip is a dance – if you hadn’t noticed! And we had to start learning the dance, basically. So Paul Lightfoot and Sol Léon, two amazing choreographers, sent over their lieutenants, their brilliant young dancers, to try and teach us this thing.

So that was Drew and I’s first introduction: getting into a room, stripping down to tights and rolling around on the floor! Which tends to break the ice. We started laughing then, and we didn’t stop laughing till the end.

He’s an incredibly mature, brilliant young actor. But he’s also an incredibly mature and sensitive and caring human being. I got that the moment I met him. I went: “Oh, OK, you’re gonna be all right, it’s fine. We’re good here.“

As a young ex-serviceman, he does look appropriately buff for Allerton. What did you do to your body to play Lee?

I didn’t do anything. I thought about trying to lose lots and lots of weight. But it was actually a pretty short period we had before we were doing it, and there was just no way I could lose it healthily. So I was like: “You know what? This is what he is.” And I just stopped eating… a bit. And then ate because I was in Italy [where Queer was shot]. I just thought: he’s a heroin addict, the weight goes up and down.

You’ve previously said that Queer is “not a story of unrequited love, it’s a story of an unsynchronised love”. Again, could you open that up for us?

They’re both equally involved in this affair, this romance, this love affair, whatever you want to call it. They’re incredibly different human beings, and they’re both looking for different things in their life at this particular moment. But they’ve come across each other.

It’s something I could relate to. It’s happened to me in my life, where you’re sort of vibrating at different frequencies. And you’re hoping that you’re going to join each other and start vibrating together at the right time. But it’s just not going to happen.

And it’s not because the desire doesn’t go both ways. It’s nothing to do with that. It’s just not to be. That’s the tragedy of the story, and that’s what we try to eke out. This very near [relationship] that could have been a wonderful thing.

I mean, for Lee’s part, he’s a bit more talkative! He has a lot to do sometimes in response to Allerton’s silences, because he can’t articulate himself the way that Lee is able to articulate himself.

So I think there’s a discrepancy there – [Allerton] basically gets a gobshite in front of him, which I think is very real. I think that’s important to note. It’s not a story that’s a one-way street. It’s very much a two-way street as far as the love affair is concerned.

Which of Luca’s previous films, or even moments in his films, impressed you, and why?

All of them impressed me, in very, very, very different ways. That, I think, is what I’m so attracted to in his filmmaking. Because each movie – fromBones and All to Challengers, or Suspiria to The Big Splash – are just so dramatically different from each other. And they’re exploring different types of cinema. And different types of genre. That I just find so exciting, for a director to have the confidence to do that. Who’s not stuck in a groove. It’s just like: I need to explore all of these things.

He’s a massive, encyclopaedic cinephile. As most great directors are. But he has such a love of it, and a wish to recreate or re-imagine great moments in cinema in his own beautiful way. He’s a bit of a genius.

How did his handling of the sex scenes in, particularly,Call Me by Your Name, Bones and All, and Challengers feed into your feelings about doing Queer’s (frankly full-on) sex scenes?

The script was very clear! It’s not like it was a big surprise. “Oh, my God, we’re doing this?” It was written down, and I went: “Yeah.” I can’t speak to the other movies. But to shy away from the sex would have just been wrong. This is what people do.

But it’s not the act of the sex that is interesting in the film. People may think so, and that’s fine. It’s what’s happening emotionally with these two characters. The fact that they’re having sex with each other is just what happens next. That’s the wonderful thing about it. That’s what we do as human beings. Gloriously.

“Masculinity or maleness doesn’t necessarily go along with toughness. Those two things aren’t [mutually inclusive]”

You’ve talked in a couple of other interviews about how this film challenges the construction and artifice of masculinity. What did playing James Bond five times over teach you about the construction and artifice of masculinity?

Probably that it’s just that – an artifice. I’m not putting it down; I’m not having a go at it. It’s glorious and wonderful in many ways. It’s just that it’s learned behaviour, as most things are.

There’s an expression I love: “the bigger the front, the bigger the back”. Which is [the idea that]: OK, what’s all this going on here? What’s going on behind? That’s what’s interesting: what’s going on underneath.

That, I think, is really important to understand. Because so much bad behaviour in the world is to do with learned behaviour. And we have to, at the very least, try and understand it. Try and analyse it. Try and make sense of it. Especially as men we have to do that.

But it really fascinates me. And maybe playing Bond has made it more of a thing for me. But masculinity or maleness doesn’t necessarily go along with toughness. Those two things aren’t [mutually inclusive]. That in itself is a deep well of interesting things to explore.

Let’s talk about the costuming. What conversations did you have with Jonathan Anderson about Lee’s look?

It was pretty quick, really. He came in and said: “I think we need to wear original suits.” I was like: “I’m all over that.” Because even if you make a suit, then age it down, and try and make it look like it’s been lived in, it never really does. So he very bravely picked two, three suits that I wear, and different shirts. All original, all from the period, including the underwear.

I had one of each, and they were all white. I’m a very messy eater, so I said: “It’s your fault if I spill beetroot down this.” But that’s what we did. And you wouldn’t have got that feel [otherwise].

When we first met, he brought a rack of things that literally filled the room. But at one end, he had these two suits and he said: “Try these on.” And I said: “I don’t have to do anything else. This is it. This is the look.” He’s a true artist, Jonathan.

You mentioned the underwear. Jonathan has said he found an “amazing guy in Montreal who is a strange obsessive over historical underwear”. Tell us about this historical underwear, Daniel. What’s it like?

[Smiles, pauses] It doesn’t have a lot of elastic. But actually it’s very nice. It’s got buttons and panelling.

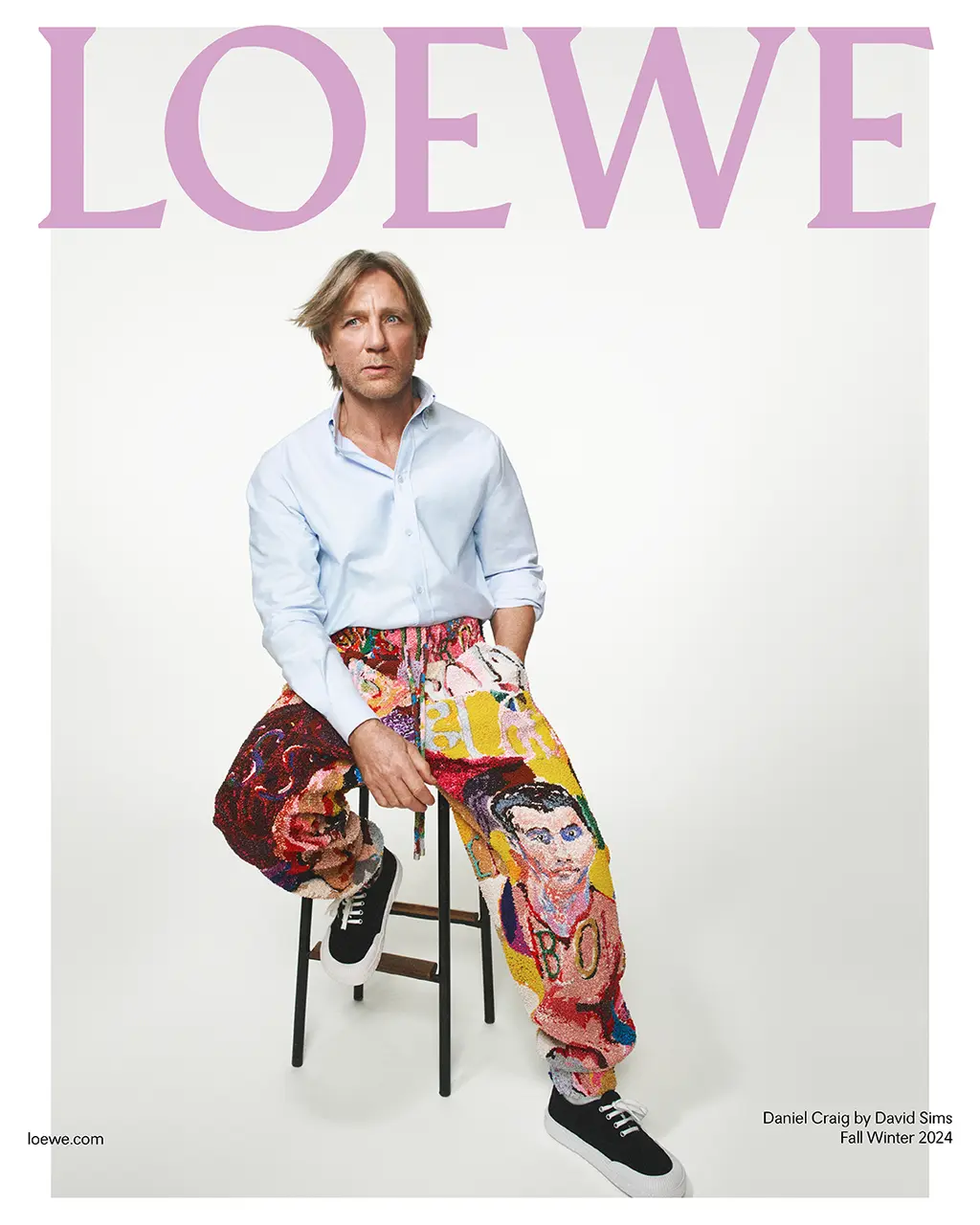

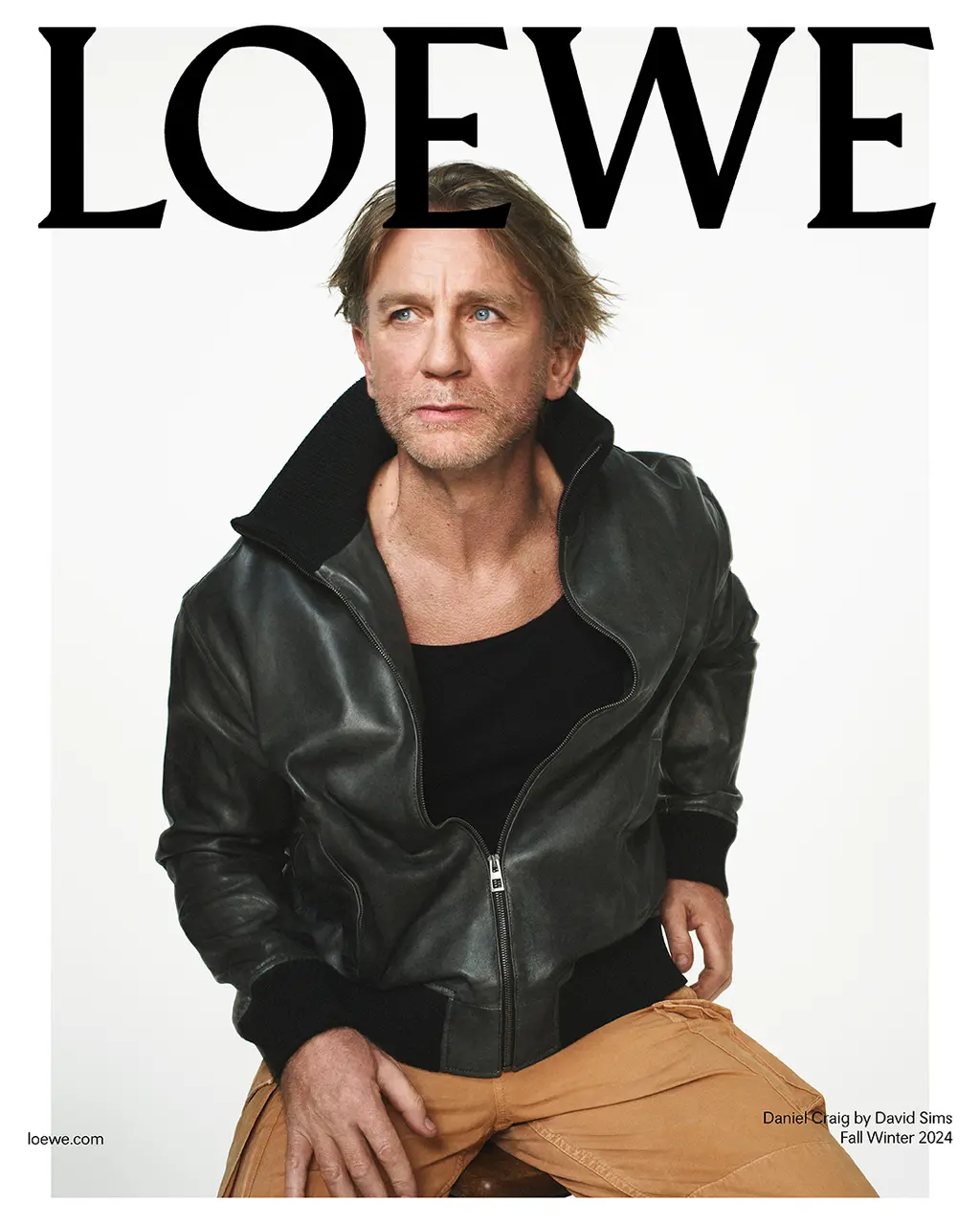

You also worked with Jonathan on Loewe’s FW24 campaign. How much out of your comfort zone was it to model, and model those clothes in particular?

Listen, I’ve been way, way more out of my comfort zone in my career than that. I just had to come and put some clothes on and have some photographs taken.

He mentioned it to me while we were filming, and I was like: “Really? I mean, I’d be honoured to do something with you.” So we got it together, he pulled some clothes, I looked at them and went: “Well, I’m not going to say no now.” If he thinks I should wear these clothes, I’m going to wear them. I’m not going to back out and get scared away.

Is there, fundamentally, a post-Bond freedom as to how you dress and how you wear your hair that you didn’t have, even in the periods between those five movies?

[Unconvincingly] Sure. I mean, there’s no thought process involved… I grew my hair a bit longer for Queer, and… post-Queer I just didn’t cut it. But I’ve grown my hair before: I had long, long hair during the pandemic. It’s not a new thing. I didn’t sit down and go [scheming voice, steepled fingers out of shot]: “Right. What am I going to do now, post-Bond? Who’s the new me?“

Your next film is Knives Out: Wake Up Dead Man. We know this is your detective character Benoit Blanc’s “most dangerous case yet”. It also seems to be his most hirsute case, from what we’ve seen of the first-look image…

Yeah. I was about to cut my hair after Queer. And I said to [director] Rian [Johnson]: “How about a long-haired look?” And he went: “Great!” So I started growing it [more].

We love Knives Out at THE FACE, not least because the magazine did appear in the second film, Glass Onion…

In a very important plot twist.

So what can you tell us about Wake Up Dead Man?

Nothing! No, I really can’t. But it’s very complex. It’s very funny, hopefully, as the other two were. But I always fear that if I say one thing, it’s a whodunnit, and people will sit and they will try and figure it out. And I don’t want them to figure it out. We’ve got to keep it absolutely schtum.

Your performance in Queer has been lavishly praised. How meaningful would it be for you to get your first Oscar nomination at this age and stage?

I’m not going to lie to you: that’d be wonderful, wouldn’t it? But you have to just roll with it. In many ways, it’s not up to me. It’s going to be what people are into at the time. But if I was given a nomination, I’d be incredibly honoured. It’s as simple as that.

As a music fan, what do you think of the use of New Order (Leave Me Alone) and Nirvana (Come As You Are) on the Queer soundtrack?

Luca always said he would. He gave me a list of the tracks he was going to use, which I’ve then promptly forgotten… So when the Prince track [17 Days] drops, because it a rare one, I’m like: “What the fuck is that?”

Look: Burroughs’ imprint on pop culture is so great, and [there’s] his relationship with Nirvana [in 1992 the author and Kurt Cobain collaborated on a track, The “Priest” They Called Him]. It’s linking the two worlds in the story. Also, it’s a major bit of alienation. It’s reminding you that you’re in a movie, and therefore, what does that trigger in you? It drags you out and puts you back in. And the New Order track is genius. How lucky we were to get it.

“I love being on a set, I love talking with people, I love having a crack”

Spotify Wrapped just dropped. What’s highest up on your list?

I don’t know what it is. [I explain the streamer’s annual, culture-grabbing marketing wheeze.] OK. Probably because of my daughter, Vampire by… what’s she called… Olivia Rodrigo. That’s been on repeat in my house for quite a while now. The explicit version, which gets a giggle every time.

Do you know what you’ve listened to most this year yourself, if it wasn’t for your daughter?

I have two iPods. I don’t like to have a phone on set. So I’ve downloaded all my music, all my CDs that I actually downloaded years ago, onto these iPods. And I just stick it on the shuffle, and it’s what comes.

It’s the way I concentrate onset, because I’m just so distracted by everything. Because I love being on a set, I love talking with people, I love having a crack. So I have to tune myself out. So it’s really random: it’s The Specials to Tchaikovsky.

Rewind, please: you have actual iPods, from back in the day, that are still working?

Yeah, but they’re jacked. They’ve got two terabytes of memory on them, which is way too much. You could fit 25 libraries into them. It just means that they’re much steadier than the old ones that used to have – I’m so boring, Jesus Christ, that I know this.

No! This is neek heaven, we’re into it.

OK! So you buy them, and they’ve basically had memory put into them. The old ones used to have the spinning wheel, and remember you could hear them spinning? They also put a different battery into them, so the battery literally never dies. I’ve got, like, 30,000 tracks on it. That’s what I use so I don’t have to take a phone on set but I’ve got my music still.

Could you bring this to our Q&A? If you whip out your iPod at Curzon Hoxton, the audience will lose their shit.

Ha ha! I will bring it.

Queer is in cinemas from 13th March. Watch this space for a report from our Q&A with Daniel. Swearing guaranteed.