The history of nameplate jewellery

Elena Joy (@halfhug) photographed by Gogy Esparza, New York

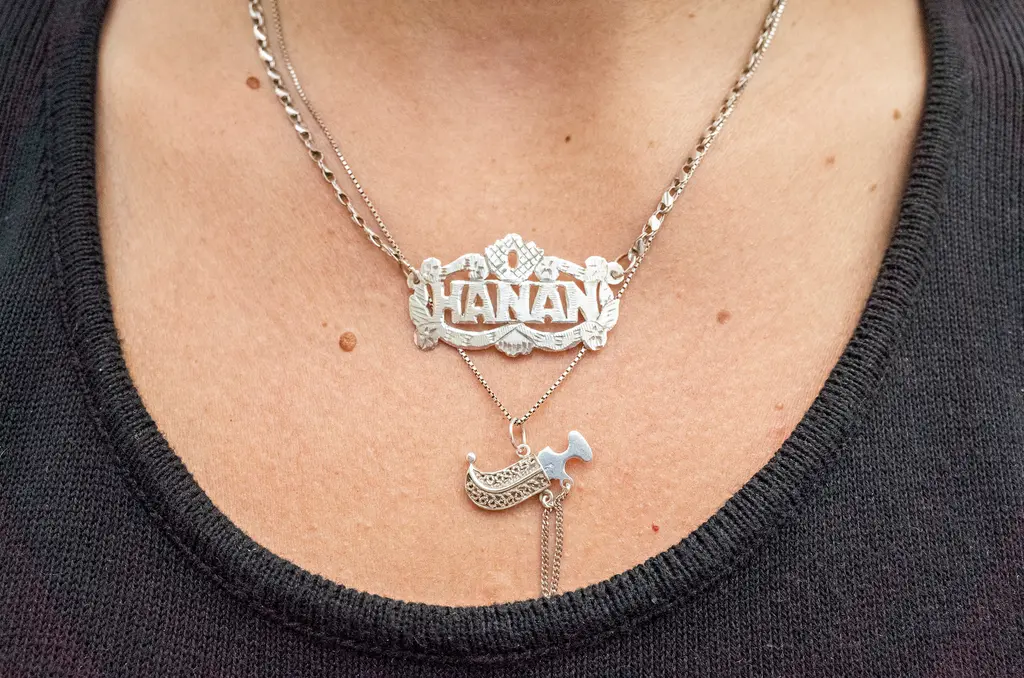

Documenting the Nameplate debunks the notion that nameplates are nothing more than fancy bits of bling, celebrating the rich, emotional history behind the pieces.

Culture

Words: Jade Wickes

When it comes to the history and cultural significance of the nameplate – a piece of jewellery that literally has your name on it – there’s no source more reputable than Documenting the Nameplate: an Instagram account and open-call photobook spearheaded by best friends Marcel Rosa-Salas and Isabel Flower.

Over the last few decades, nameplates have arduously withstood the industry’s fickleness in the face of trends. They’ve appeared regularly in films, TV show and around the necks – or, in Beyoncé’s case, body – of countless celebrities: Kim Kardashian, Rihanna, Lil’ Kim and Nicki Minaj. Hell, even some of last year’s Love Island-ers were credited with prompting a surge in demand, after contestants wore them on the show.

But there’s far more to all of this than meets the eye, and Documenting the Nameplate seeks to celebrate the power and panache of nameplates while debunking the notion that they’re nothing more than fancy bits of bling. Sure, nameplates have now largely been adopted into mainstream culture, but that doesn’t mean the rich history they’re steeped in should be ignored, underestimated or worse, lumped in with fashion’s recent revival spiral. That’s why, over dinner in 2015, Rosa-Salas, a cultural anthropologist and documentary filmmaker, and Flower, a writer and editor of design magazine Deem, had an epiphany of sorts.

“We were discussing [how] even though nameplates are a global phenomenon and incredibly special to so many people we know, to our knowledge, they had not yet been formally studied and written about,” they say.

This was the starting point for a deeper investigation, culminating in the first episode of the pair’s podcast, Top Rank, a year later: “What we learned was so rich that we knew [it] warranted an even deeper dive as well as a visual component. After publishing an academic article on the subject, we decided that photography would be our next step.”

Across film and TV, nameplate jewellery is sometimes associated with a kind of throwback glamour. In Euphoria, Maddy Perez’s signature nameplate necklace – a sold-out, custom number courtesy of BP Jewelry – is a key component of her character’s Queen Bee seductiveness.

But for all of nameplate jewellery’s current pop cultural omnipresence, they’ve actually been a continuous fashion staple for decades, if not centuries – especially in Black and Puerto Rican neighbourhoods in New York City, and then the world, argue Rosa-Salas and Flower.

“One of the reasons we find [they’re] popular with so many different groups of people is their fundamental emphasis on the name,” they say. “Names are the essence of who we are and tell important stories about our lives and family histories. There’s something to be said about the desire to wear one’s name for others to see and how this can be a political expression of personhood.

“Especially for groups of people who have been marginalised because of racial, ethnic and class-based social hierarchies,” they continue. “Nameplates can possibly offer a sense of visibility in contexts where recognition has otherwise been denied or diminished.”

In the same way on-screen portrayals of nameplate jewellery can help elevate these pieces, sometimes they can actually water down what nameplates represent. In an episode of Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw infamously refers to her nameplate necklace as “ghetto gold”, a flippant comment which stuck with the culture for years – and brought it an unexpected audience.

“The show brought the nameplate into the homes of a wealthier, whiter, cable-viewing America,” Flower and Rosa-Salas explain. “Its tremendous popularity also led to major media outlets rewriting the nameplate necklace’s history as beginning with Carrie Bradshaw. Unfortunately, this narrative oversimplifies the dynamic and cross-cultural resonance this style had for a century prior.”

The pair point out that silver name brooches and bracelets were popular in Victorian England, while in Hawaii, at the turn of the 20th century, name bracelets evolved into Hawaiian Heirloom jewellery. Later, by the 1970s, nightlife and disco “fostered a cross-pollination of people from different ethnic and racial groups, which brought accessories like the nameplate into a wider circulation,” they say. Once hip-hop came around, nameplates became even more ubiquitous, as fans of the genre took style cues from the likes of Big Daddy Kane and Run DMC. The rest is history.

The respect the pair apply to nameplate jewellery, alongside its fascinating cultural roots, are at the heart of their ongoing project, with an open-call photobook set for an autumn release. In their words: “A nameplate attains its specialness not only from its unique personalised design – but also from the significance it holds to the person who wears it.”

Submit your nameplates via Documenting the Nameplate’s Instagram page or website.