Pusha T’s master recipe

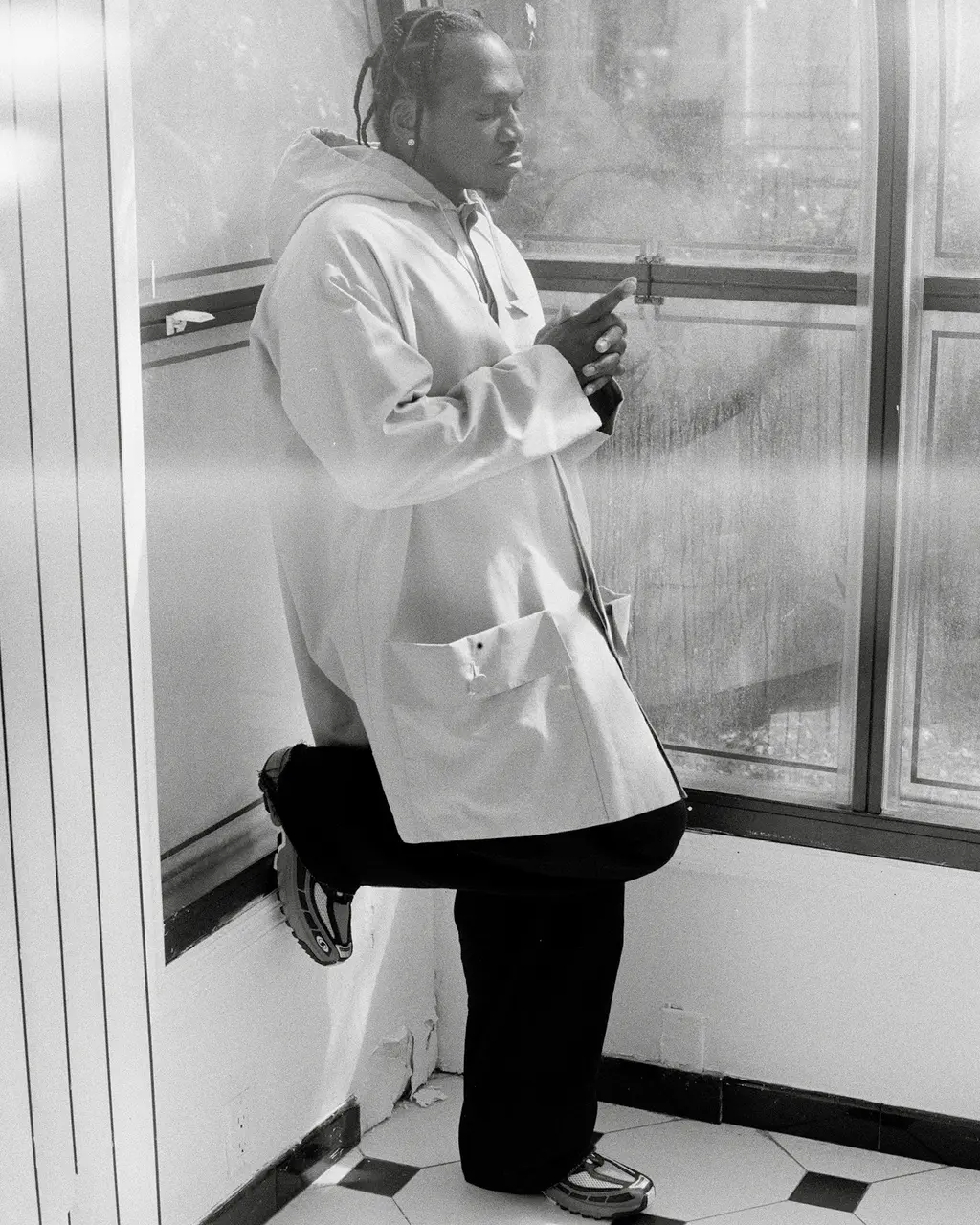

Pusha T wears jacket DIESEL, shorts SUPREME X DICKIES

Digital cover: While hip-hop’s trends have come and gone, the veteran rapper has never gone out of fashion. In his interview with THE FACE, he praises Kanye West and Pharrell for keeping his sound fresh on new album It’s Almost Dry.

Music

Words: Matthew Ismael Ruiz

Photography: Quinn Batley

Styling: Christopher Smith

Pusha T's personal stylist: Marcus Paul

To the uninitiated, the news that Pusha T – a rap star notorious for gritty tales of the cocaine trade – had cut a diss track aimed at a sandwich may have seemed perplexing. And truly, his words on Spicy Fish Diss Track, a recent song anchoring a campaign for fast food chain Arby’s rival fish dish, are as incisive and ruthless as any ever aimed at McDonald’s Filet-o-Fish.

But the dissonance is only startling if you haven’t been paying attention. Because while Pusha has long painted himself in his music as a grizzled veteran of the streets, the rapper born Terrence LeVarr Thornton has understood better than most that there’s more than one way to make a living writing raps.

Besides, he and McDonald’s already had beef.

Back in 2003, when Pusha was recruited by Pharrell to work on the jingle that would become McDonald’s famed I’m Lovin’ It theme, he was happy to invoice and call it a day. But as years passed and the theme became ubiquitous, he came to realise just how much money he’d left on the table. “At the time I was like, ‘oh man, this is great’,” he says. “Not knowing that would be the theme song for McDonald’s for the next, you know, 20 years to come.”

A decade later – and wiser – his team read the tea leaves of the ever-growing ad market and encouraged him to start dabbling in sync-friendly EDM collaborations. And when Arby’s sampled a riff from the Skrillex remix of his 2014 Yogi collaboration Burial for their “We Got the Meats” campaign, Pusha took the long money. “I own 40 per cent of that song,” he explains. “So every few months when they renew it, they have to cut the check.”

This is what it means to be a successful recording artist these days. It’s not enough to be a master of your craft – you must also master the business. Because if you don’t, someone, somewhere is taking advantage of you. Someone is getting rich off your labour. Why shouldn’t it be you?

Of course, it starts with the music, and Pusha T remains in the spotlight because he’s very good at making rap records. His new, 12-track album It’s Almost Dry is laser-focused, eschewing the now commonplace bloated tracklist designed to juke streaming numbers in favour of a quality-over-quantity approach that deserves respect and repeated listens. The primary producers are Pharrell and Kanye West, responsible for some of Pusha’s most enduring work, like Hell Hath No Fury – the classic 2006 album by his former group Clipse – or his red-hot 2018 album Daytona, respectively.

It’s unlikely that Pusha foresaw such a future for himself growing up in Virginia Beach. Like many of his neighbours, his first taste of the high life came when Teddy Riley – super producer and architect of the New Jack Swing genre – came down from Harlem to set up shop in the early ’90s. The beach town’s streets were soon graced by the yellow Ferraris and entourages that accompanied the various superstars (including Michael Jackson) who would make the pilgrimage to record with Riley at his Future Records studio, offering a glimpse of the luxuries afforded to world-famous recording artists.

But it was his older brother Gene, aka Malice, his future partner in Clipse, who introduced him to the actual process. Pusha would beg Gene to take him along to sessions at the house of a local producer named Timbaland – which he did, begrudgingly, at the behest of their mother.

But despite his deep associations with Virginia, it was in New York that Pusha T would come of age. In the late ’80s he spent his childhood summers in the Bronx, where he was born, with his grandmother, out from under his mother’s watchful eye, free to roam her apartment building and its surrounding blocks in a way he never was down south. He soaked up the local flavour, becoming enthralled by golden age hip-hop greats like Eric B & Rakim and Big Daddy Kane. He saw the dope boys out on the corner doing their thing, but he also saw order in it – the way they held doors open for his grandmother and managed the chaos of a neglected community.

“The Bronx really shaped a lot of my independence,” Pusha remembers. “As a youth, my mom had me under her thumb ‘cause we were in the south. But [when] I would go see my grandmother, and I’d be on Gun Hill Road, I could go play and I could run errands for her. I probably wasn’t going anywhere but four blocks, maybe, but you know, it felt like a metropolis.”

Pusha T wears jacket PRADA, pants BALENCIAGA, shoes SALOMON

Pusha T wears jacket PRADA, pants BALENCIAGA, shoes SALOMON

Back home in Virginia, the rap game looked a lot like the dope game. Both were on the street and underground, plastic packages sold illicitly behind the 7 – 11. Who was dopest wasn’t reflected by a chart but by word of mouth. You were either physically in the streets, or you weren’t. When Pusha and Malice came up with Clipse, the charts were in the trunk of the mixtape dealer’s car over at Norfolk State University. If the dealer doesn’t have your mixtape, your mixtape ain’t shit.

Of course, all that feels like ancient history now. Somewhere along the line, Pusha’s customers moved from the streets to the tweets, from on the block to online. The blog era of the mid-late ’00s was a transformative period in the music industry, a post-Napster free-for-all in which the means of distribution had been wrested from the labels by independent curators, where a local act could go national – or even global – seemingly overnight.

Pusha recalls the moment where his own story shifted quite vividly. It was a 2006 gig at the Knitting Factory in New York, where he was promoting the latest entry in the now-legendary mixtape series with the Re-Up Gang, Clipse’s crew with Philly rappers Ab-Liva and Sandman. At this point Pusha still had one foot in the dope game and one in the rap game, and when he realised that We Got It 4 Cheap, Vol 2 wasn’t moving units in the street, his frustrations mounted. They reached a boiling point at the show, when that disconnect from the streets was laid out in front of him.

Pusha T wears jacket DIESEL, shirt STYLIST'S OWN, pants DIESEL, shoes SALOMON, accessories PUSHA T'S OWN

The room was packed, but with hundreds of white hipster kids draped in streetwear. He took out his frustration on the promoter, cussing him out mercilessly. He wasn’t swayed by his insistence that “the blogs” were hyping it up for him… at least until he hit the stage, saw the rabid crowd chanting along with the lyrics, and felt it himself.

“They had on the same clothes I had on, they had on the same hoodies. They were pointing at me, like, ‘oh man, you got the Bathing Ape general jacket, oh my God! They only made five of those!’ What? Why do y’all even know this? I didn’t even understand. Those same kids are now my fans for life, have been loyalists for all this time. And they’re the reason why I can [rap] fashion bars. They’re the reason that I can say a brand or talk about some fly shit, and they help translate it back to the streets, too.”

Around 2010, Clipse started to come undone, a catalyst being the 32-year prison sentence handed down to their confidant Anthony “Geezy” Gonzalez (he was released after serving eight and half). In addition to managing their early career, Gonzalez ran a club called the Encore Lounge in Norfolk, Virginia, and admitted to helming a drug ring that distributed more than a ton of marijuana and 100 pounds of cocaine from 2003 to 2009. He claims that much of the vivid detail found in the Clipse’s cocaine tales were drawn from his own life and experiences, as opposed to theirs.

PUSHA T

The Clipse brothers pursued divergent paths: Malice found Jesus (and adopted the name No Malice from 2012 until very recently) and Pusha found Kanye. Drawn into the fold at G.O.O.D. Music, where he would later be named president, Pusha leveraged high-profile guest appearances on the label’s G.O.O.D. Friday singles and West’s world-conquering opus My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy into a successful solo career. Over his albums My Name is My Name (2013), King Push – Darkest Before Dawn: The Prelude (2015) and Daytona (2018), Pusha carved out his formula of cunning wordplay, crystal-clear delivery, wild ad-libs and an ear for stop-you-in-your-tracks beats that have never gone out of style.

Pusha’s relationship with Ye is a curious one. Based on mutual respect, they appear to honestly critique each other’s work, to demand the best from each other. It’s no accident that Pusha emerged from the bizarre scene at Ye’s Wyoming compound in 2018, where he recorded five albums – including one for Nas, one for Teyana Taylor, one for his Kids See Ghosts project with Kid Cudi and his own solo effort, Ye – with the seven best beats for Daytona.

Even as Kanye West’s influence – and ego – ballooned to gargantuan proportions, Pusha remained unbothered. Ye could wear a red MAGA hat in public while Pusha compared the Trumpian signifier to a KKK hood, and somehow the two can find a way to break bread and still make compelling art together. It’s a level of courtesy and respect not afforded to everyone in his circle. Just last year Ye disowned John Legend and Big Sean for publicly criticising his political views.

“That comes from having my own stance,” Pusha explains. “As much as me and him agree, we disagree a lot, and we speak candidly about how we disagree with each other. But at the end of the day, we know that we both have different agendas. Some I ain’t compromising on, some he ain’t compromising on. We are never here to damage each other, though. Me and him can argue back and forth all day. But I ain’t gonna let you do it. We can agree to disagree, but I’m not here to get on TV and let somebody drag him, you know what I’m saying?”

For It’s Almost Dry, Pusha T found explosive creative chemistry with Ye and Pharrell – the superstars with whom he feels most comfortable but who, paradoxically, don’t let him get too comfortable. After all, who else is going to have the chutzpah it takes for Pharrell to tell Pusha he was disappointed in his verse on the track Hear Me Clearly, which initially appeared on Nigo’s album, suggesting he sounded like a “mixtape rapper”?

“For what it is that I do, street rap-wise, they understand the level of credibility that I’m trying to keep, the standard,” he says of enlisting Ye and Pharrell, praising their endless thirst for innovating rap production. “You have to find new ways. If we are gonna be great, it has to sound new. If it don’t sound fresh, we are not using it.”

It’s funny to hear Pusha talk about staying fresh, considering he’s rapped mostly about selling dope for his entire career. Even as he gets further and further from the actual streets, he continues to refine and play up to his coke kingpin persona, rapping in a fake blizzard during a TV performance of It’s Almost Dry’s lead single Diet Coke, for example. At times, it has felt extremely one-dimensional, one of the few legitimate criticisms of his work.

After years of rapping about selling drugs – and watching his close confidant lose his freedom over it – is this really all he has to talk about?

The way Pusha sees it, he’s a genre formalist, working within a codified format to hone his skills as an MC. “I’m trying to be the Martin Scorsese of this,” he says. “And I ain’t never asked for Martin Scorsese to not make a gangster film. I would never do that. That’s what he’s great at.”

So Scorcese has made a few non-gangster movies, but the point stands. Why toss out a winning formula when you can infinitely tweak it in pursuit of perfection?

Pusha T wears shirt TELFAR, vest CARHARTT, pants CARHARTT, shoes TIMBERLAND, gloves STYLIST'S OWN

There’s a reason the drug dealing street tales do so well, for both with the people that live them and the suburban hypebeasts who exoticise them. The story of the drug dealer in America is one of the anti-hero, an underdog fighting and clawing for a piece of the American Dream. Even when they win, and the signifiers shift from Lincoln Continentals to “million-dollar autos”, they still represent the triumph of the marginalised, the rare success that keeps the dream alive for so many left behind.

It’s not just Pusha who finds comfort in that lane. Clipse fans have long been desperate for a reunion, and Malice finally agreed to hop on a track (Use This Gospel) with his brother for Ye’s gospel-centric Jesus Is King album. Despite dropping the “No” from his name, it’s clear Malice’s relationship with God is at the forefront of his mind – even on his latest appearance on I Pray For You, the closer on It’s Almost Dry, he’s considering his soul’s salvation in the wake of their past transgressions.

But while his brother’s devotion to religion has likely played a part in his resistance to reunite the group, Pusha suggests it’s not the only one. “I feel like every time we drop something, or if he does something like this recent thing, people get back into the conversation of: ‘Oh, his brother was so much better than him.’”

Looking backwards at the Clipse records he made with his brother is just one reason for Pusha to consider his legacy, to ask: “What will I leave behind when I finally go?” It’s more than just conceptual. Pusha and his brother recently lost both their parents over a period of just four months, yet were also blessed by the birth of Pusha’s son Nigel Brixx (even the boy’s middle name is slang for coke) with his wife, Virginia Williams. His personal goals may be private, but as an MC, what does he have left to prove?

With an eye to the future, he’s started to mentor new talent, like his new signee Yvngxchris, a viral teen rapper on TikTok who is on tour with Lil Tecca. While Pusha offers the wisdom and connections that come with experience, Yvngxchris offers perspective of his own, a digital native who has managed what Pusha did in reverse, leveraging an online audience into one IRL. Pusha has watched other rappers fade from relevance as the industry moves forward and leaves them behind, and it’s clearly a future he’d like to avoid.

As long as his finger remains firmly planted on the pulse, at the age of 44 it’s still hard to imagine Pusha ever falling off, even if he only stops rapping about selling cocaine to throw darts at a fast food chain’s fish-based option.

“My goal right now is to see how far I can take it,” Pusha says. “I love what I’m doing so much, and I feel like I’m hitting my stride in regards to creativity. I’m opening up new chambers. And this is the era, the guys my age are gonna show us: ‘Are we gonna be able to do this forever?’ It feels like they’re still trying to age us out, unlike other genres. They don’t age out U2, you know what I’m saying?”

PHOTO ASSISTANTS Mark Custer & Diego Donival STYLIST ASSISTANT Noel Delfiner GROOMER Nanase Ito PRODUCTION Camera Club SPECIAL THANKS TO Junior Suriel, Shivam Pandya, Picture House & Andrew Samaha