Orange Culture on a decade of shaking up the Nigerian queerscape

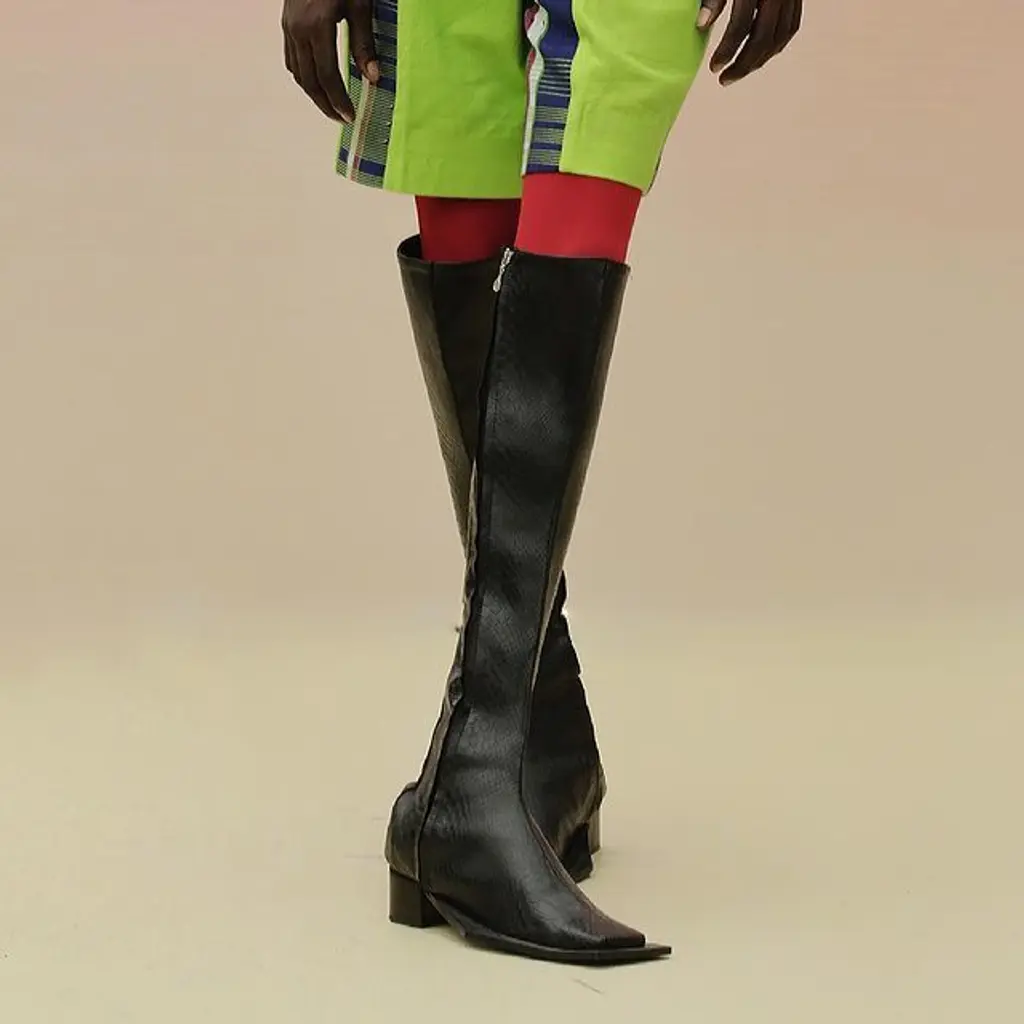

Orange Culture AW21, Look 22, photography Michael Oshai

Ten years and 20 collections later, the rebellious Lagos label is still fearlessly making a case for androgyny against a conservative backdrop.

Style

Words: Vincent Desmond

When Nigerian designer Adebayo Oke-Lawal founded Orange Culture in 2011, a fashion brand like his didn’t exist in his hometown of Lagos. But speaking to him a decade later, he’s quick to remind you that, over time, the androgynous menswear label has established itself as more than a brand – it’s a movement.

Since it was launched, Orange Culture has continuously pushed against the boundaries and ideals of traditional masculinity in conservative Nigeria through its riotous approach to menswear design. With it has come praise: in 2014, LVMH selected Orange Culture for their Young Fashion Designers Prize, where 1221 designers were whittled down to 29. A year later, Oke-Lawal displayed his designs at the International Fashion Showcase organised by The British Fashion Council during London Fashion Week. And before the likes of Lupita Nyong’o, Chimamanda Adichie and Dua Lipa wore Orange Culture, it had become the first African brand nominated for the Woolmark Prize, where past finalists include Matty Bovan, A‑COLD-WALL* and Bethany Williams.

Oke-Lawal’s work features vibrant colours, plunging silhouettes and the subversion of traditionally feminine cuts such as fitted crop tops, oversized pussy bows and sequinned vests. But Nigeria’s conservative political outlook on sex, gender and queerness has meant Oke-Lawal has had to deal with daily death threats via social media, emails and in person. As it stands, there is no legal protection for LGBTQ+ people in Nigeria and gay sex is punishable by up to 14-years imprisonment – in some parts, death by stoning.

“When I first started my brand, the reception wasn’t great at all,” Oke-Lawal says. “People hated the idea of me questioning gender stereotypes and confronting them with androgyny. I cried after my first collection.” But after “a few tears”, the designer decided that the conversations he was initiating were vital in raising awareness on LGBTQ+ communities in his hometown. He decided to plough on.

Recently, Oke-Lawal has used his platform to raise political awareness again, this time highlighting extreme police brutality in Nigeria and the protests of the #ENDSARS movement. Reiterating his stance several times on social media, the designer even halted production and paused orders taken on the brand’s website as a way to bring attention.

“I’m inspired by emotional interactions, confrontations and societal restrictions, norms and stereotypes,” the designer says. “I usually don’t fit into [boxes], and so my desire is to question and, a lot of the time, push people to do so, too.”

For the designer, drawing upon his personal experiences is a key element to the brand – and its success. “My collections are always inspired by things I feel,” he adds. “I must feel it and be able to draw from it.”

Over a decade in the game and the rebellion of Orange Culture is stronger than ever. The brand’s latest collection, Honest, for AW21, explores father/son relationships and, more specifically, the acceptance between parent and child. It came from Oke-Lawal’s own experiences growing up with a father who thought differently to him, and who didn’t quite understand cultural interests. Through androgynous ’70s cuts, like slinky flares, puffed-out shirts and trippy prints, Oke-Lawal set out to depict a young boy stealing relics from his father’s past – or wardrobe – using vintage fabrics such as aged corduroys, denim, mesh, cotton, crinkled chiffons and raw silks.

“For me, fashion continues to be an important way to investigate social dynamics, and I wanted this collection to truly underscore the rare but necessary condition of father-son relationships,” he says. “Particularly on this side of the world.”