Pop Smoke’s London pilgrimage

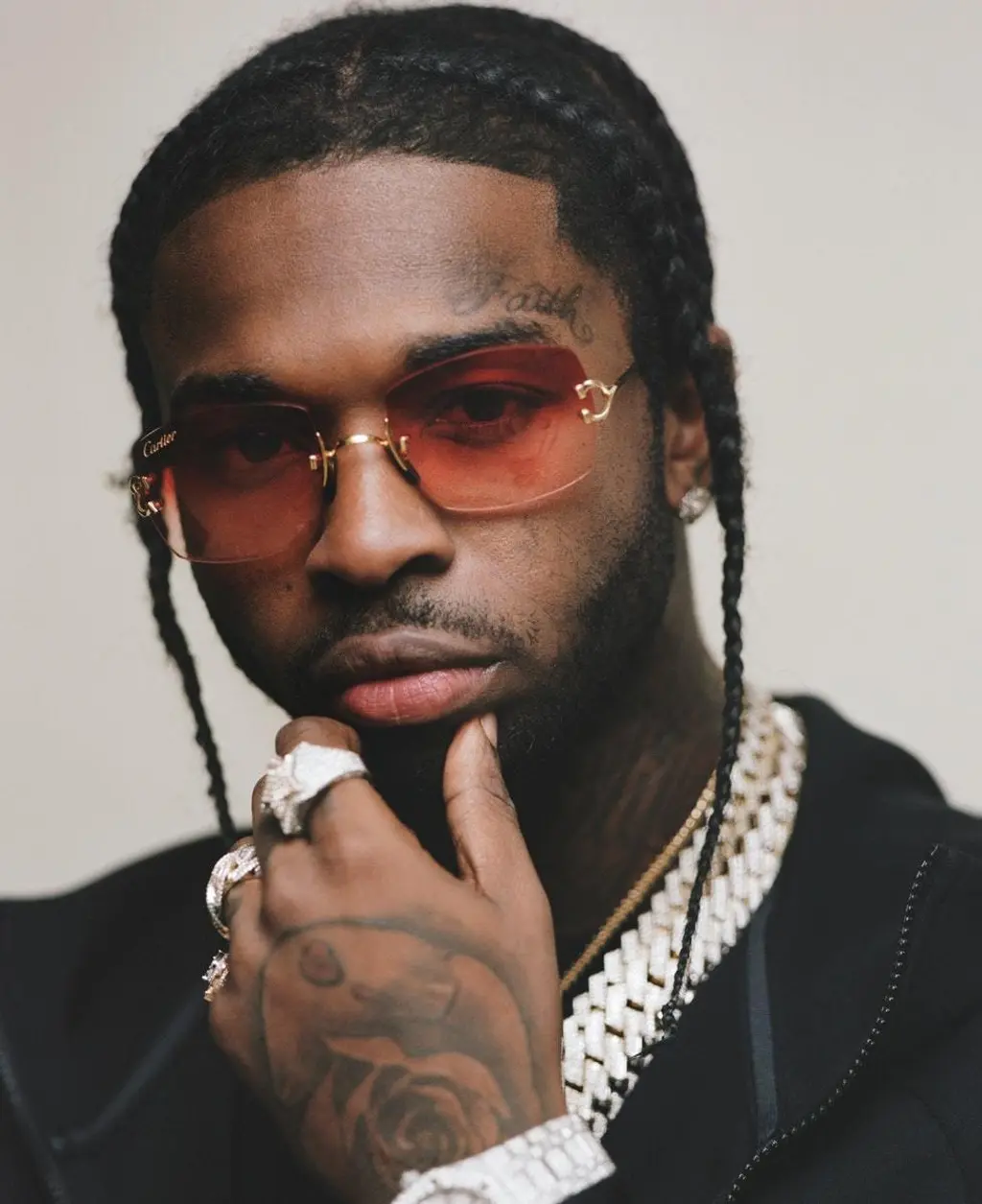

The breakthrough Brooklyn rapper and his UK producer 808Melo discuss drill music as a global movement.

Music

Words: Colin Gannon

Photography: Oscar Eckel

$50,000 in stash money, a BMW 6 Series with cream interiors, one ring, and a solitary gold bracelet: Pop Smoke entered rap with more than most. But he’s still taken aback by the luxury he’s now surrounded by. “Yo, it’s got a fucking balcony!” the 20-year-old howls in awe as he enters his hotel room in Shoreditch, east London.

The rapper born Bashar Jackson floats at the vanguard of the blossoming Brooklyn drill scene, emerging as a new type of New York rap star after the successes of songs like Meet the Woo, Dior and his monster hit Welcome to the Party – which has spawned remixes by Skepta and Nicki Minaj.

The drill genre was a Chicago-based rap wave pioneered by the likes of Chief Keef, Young Chop, Fredo Santana and Sasha GoHard in the early 2010s, which surged alongside record-breaking violent crime rates in the city. It may have not sounded dissimilar to trap music to the untrained ear, but it embraced the darkest aspects of rap and has slang, cadences and sonic details particular to it. The UK wave of drill began around 2013 and has surged to become one of the most dominant forms and controversial of London rap in recent years. Now the transatlantic drill exchange continues, with Pop Smoke is bringing the London sound to the Brooklyn scene.

Today, Pop Smoke is with his UK-based producer 808Melo, who crafted the eerie beat for Headie One and RV’s controversial hit Know Better. The pair are sitting attentively on a grey L‑shaped sofa, visibly giddy in one another’s presence, laughing and cackling over their recent trip to LA and the promise of unleashing their newest batch of songs.

The word that Pop Smoke uses most frequently during our chat is “movie”, an apt choice given his improbable rags-to-riches story over the last several months. His hometown, Canarsie, is a “movie”; his new life is a “movie”; his sophomore mixtape sounds like a “movie”; and his planned future as a mogul is, without a doubt, the stuff of “movies”. Dressed head-to-toe in a black designer tracksuit, sporting fresh-out-of-the-box black Nikes with streaks of glossy silver, he exudes confidence, his Brooklyn accent as drawn-out and vowel-heavy as it is on tape. His mother once said he had a voice for rap; she was right.

Pop Smoke’s music gives the impression of a dyed-in-the-wool street dude unwilling to open up. Much to the contrary, Pop Smoke is excitable, carefree, and charming in person. He’s got a broad smile, and if you had only heard his stomp-on-your-face songs, you might easily confuse him for a menace. When I tell him that there are drill rappers in Ireland, his sunglasses-covered eyes seem to light up as he lets loose a series of increasingly specific questions: “There are black people in Ireland?!”, “What type of food they got in Ireland? They got oxtail?”, “So what’s y’all go-to meal? Y’all cook macaroni?”.

While browsing YouTube for beats last year, Pop Smoke happened to fall upon one called Panic by the then-unacquainted Melo, who at this point had only worked with one American artist, Brooklyn drill pioneer Sheff G. Pop Smoke was mesmerised by the bristling drum work: as a youngster, he played African drums by hand in his local church, so he appreciates concussive thwacks when he hears them. “When I heard his beat and them fucking drums – the way he dragged them drums – it stuck with me,” he says, his face screwing up in positive disgust.

Eventually, Pop Smoke flew Melo (who’s from Ilford in east London) out to New York, where they recorded much of what would become Smoke’s debut mixtape, Meet the Woo. Springing from a London scene that often regurgitates the same stuttering drum patterns and whirling basslines, Melo’s beats are distinctly crisp and layered. “My style of UK drill – ’cause there is a lot of UK drill beats out there – is completely different to these other ones. You know Welcome to the Party, it had that bassline that’s like grime. I wouldn’t say the beats are grime, it’s just UK drill and the way I do it.”

Pop Smoke flashes a knowing grin at his comrade as he sketches out his style: “I ain’t heard nobody’s beats like [Melo’s],” he says, sternly, as they both erupt in laughter for probably the twentieth time. Even if the evolution of the drill sound – from Chicago to London to Brooklyn – isn’t very obvious or linear, Melo points to a shared DNA. “Drill, in general, is dark. It’s not happy or anything.”

Throughout his adolescence, Pop Smoke struggled to stay focused. He attended at least nine different schools, and as part of a diversion program connected to a weapon charge that has since been dismissed, Pop was forced to wear an ankle monitor. It’s always been strife, even if there were bundles of cash stowed away somewhere safe in his house. When he was 16 and beginning to earn money for himself independently, he purchased his first car, a Pepsi-blue beamer. Prior to this, life was dramatically different. “Shit was hard,” Pop Smoke says matter-of-factly, preferring not to divulge too much about his past.

Read next: Bally On Me: Why UK rappers cover their faces Alter-egos, privacy and surveillance are just some of the reasons behind drill’s masks and balaclavas.

Long before his music muscled its way into rap consciousness, Pop Smoke went viral in New York, leading to minor local celebrity where people recognised his face every other day. This brush with virality prepared him somewhat for his sudden come-up. “There was a whole bunch of police surrounding me, grabbing me up,” he recalls, slightly smirking. “And I just did some ninja shit [to escape], gotta out there, and ran. It went viral. Shit was lit.”

Exactly six hours later, Pop Smoke waltzes onstage at the Islington Academy venue with a bottle of liquor in-hand, shirt unbuttoned, and gets straight into it. After being warmed up – or, more accurately, riled up – with hits from Chief Keef, Polo G, Roddy Rich, Poundz, and J Hus, the crowd’s constellation of iPhone cameras zeros in on their new hero. A normal teenager from Canarsie, Brooklyn who became obsessed by drums he found on a beat made by someone half-way across the world. “We found the formula,” Pop Smoke had said earlier that day about his and Melo’s chemistry. His life’s a movie now. So much so that he promises that Meet the Woo II, his sophomore tape’s working title, will be “happier”.

“I make music for that kid in the hood that’s gotta share a bedroom with like four kids – the young kids growing up in poverty”

Pop Smoke

New York and London have different styles, but they all spawned from Chicago. What, if not the sound, ties the scenes together?

The New York and the UK [scenes] is like the beat. Chicago comes in there with what we’re talkin’ about. Like what we saying on the track.

Pop, would you say you related more with the energy of the London sound than the Chicago originators?

I definitely relate – although not one more than the other. It’s like, there are guys are out here just like me, just like us back home. Look at fucking 808, he look like me. We all about the same thing – we all the same, bro. We just cut from different parts of the world.

You were recently asked if you had a girlfriend and you replied that you have your sister and your mom.

They’re important. And my pops too – that’s my boy.

You describe yourself on Hawk Em as a “Double‑G: Gangster and gentleman”.

A mixture. You gotta have that, you know. It’s hard to explain; you just are that. You gotta know how to speak to ladies. That’s just how I see it: a gentleman is a way you carry yourself. Gangster also don’t mean you a criminal.

What does it mean?

It means you know how to move. You gotta know how to move in different environments. Somebody might not know how to move in those types of ends, and then when you go to a more obscure spot, they won’t know how to move either. You understand what I’m trying to say? I’ve never really explained that before.

Has you life changed since Welcome to the Party blew up?

My life been changed since I was a kid. I went viral as a kid before rap, so I know about going viral, and not being able to go outside ’cause people know you and shit. With the music, though, when I heard that shit on the radio? That’s when I said, ‘My shit is going up. Poppy, you doing something’.

You were on this kind of unstoppable rise, and then the Rolling Loud incident happened, where you and a couple of other drill artists were taken off the bill by the police. How did that feel?

It didn’t feel good. I was disappointed. Hopefully y’all will see me at the next Rolling Loud.

The police have been shutting down shows involving black rappers here for decades now. With drill, it’s gotten worse. They’ve banned some artists from recording, censored certain lyrics, and threatened artists with jail-time if they don’t comply.

Pop Smoke: They go to jail?

Melo: Yeah. They’ll go to jail.

Pop Smoke: If you say something?

Melo: If you say some shit, yeah. ’Cause [UK drill rappers] are dissing everyone now.

Pop Smoke: This is where I’m different: I don’t really be talking about other people like that. I talk about my people, and my life. I’m not really into talking about that other shit. And if I do, it might be subliminal. You not gonna hear me say names or send shots – nah, we not into that.

Do you have any message for people who find themselves censored or their shows affected like you?

Just keep doing y’all thing. The scene out here is going crazy; I love that shit.

“I make music for that kid in the hood that’s gotta share a bedroom with like four kids – the young kids growing up in poverty.”

Pop Smoke

In a conversation about 6ix9ine, you said you avoid all the drama and beef that comes with social media.

6ix9ine is a weirdo. [He] had too much time on his hands. Me, I’m not really into that internet business.

Melo, do you use social media much?

No, I don’t wanna be in the limelight like that. I don’t wanna be famous. I’d rather have money. I don’t wanna have my face out there and stuff like that; I don’t want my girlfriend and my family out there. There’s bare stuff out there, like The Shade Room and all that blah blah blah. There’s always commotion, and I’m not involved in all of that.

Pop, do you relish the fame?

Pop Smoke: I’m a rapper.

Melo: It comes with it!

Pop Smoke: It comes with it. Obviously, there are people watching me, so I just wanna be a good role model for kids that are watching me. I ain’t trying to lead them the wrong way.

Who do you make music for, then? Is it for these kids you refer to – are they who you hope to inspire?

I make music for that kid in the hood that’s gotta share a bedroom with like four kids – the young kids growing up in poverty. I make music for that kid who got beef, thinking about how, when they go to school, these people might try kill me but I still gotta get my diploma for my mom. I make music for kids like that who know they just gotta keep going, that there’s a better way. That’s who I really make it for. Obviously it got bigger and it’s for everybody now – people all across the world fuck with it now – but I really make it for them. The people who really need some inspiration.

Read this next: How do young Muslims feel when rappers reference Islam?